Baikal in My Life

Michael GRACHEV — Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Dr.Sc. in Chemistry, Director of the Limnological Institute of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Irkutsk), State Prize winner, Karpinskii Prize awardee. Main research interests: molecular enzymology, paleoclimate, analytical chemistry. Prof. Grachev contributed to the elaboration of the Law on Protection of Lake Baikal

First Meetings

A picture has carved itself into my memory: it is 1944, a difficult time, war. I am five years old. My mother and I are traveling by train to Vladivostok. It is a long ride. People on the train say that soon we will come to Baikal, not a lake, but a sea! Finally we come to Slyudyanka. Fishermen are selling omul. The sweetest delicacy for me up to this point had been boiled carrots. And here we find omul, and the exotic smell of the smoked fish tantalizes our senses. This is my first meeting with Lake Baikal, and it immediately presents itself in the role as a provider of food.

My second meeting with Lake Baikal is an elementary school textbook: several lines about the deepest lake in the world.

Further: “Popular Scientific Literature,” a series of thin brochures printed on gray paper with excellent drawings: how a radio is put together, how a light bulb is made… My mother bought these brochures for me in unbelievable quantities. The famous author Perelman gave a gruesome example: if all of humanity were drowned in Lake Baikal, its level would rise by only five millimeters. This I could not forget.

Later, in the 1960s, Gerasimov’s famous film “By the Lake.” A picture: winter, sun, magnificent icicles on the shore of Lake Baikal, and nearby we see the young heroine. The entire USSR felt sorry for the lake; people found the pictures of the unique water purification structures of the Baikal pulp and paper plant unconvincing.

In 1987, academician B. A. Koptyug unexpectedly asked me if I would agree to go to Irkutsk to head the institute in charge of scientific research on Lake Baikal. A great honor and a great challenge. Can I handle it? Fate… There was no doubt: I’m going.

An Intersection Of Roads And Fates

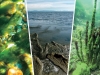

What is sacred Baikal like? A typical glacial lake lasts ten thousand years. It gradually becomes covered with silt, turns into a swamp, the swamp is overgrown by forest, and… the lake is gone. Baikal, on the other hand, is tens of millions of years old — 2,500 times more! Imagine a person who lives 250,000 years instead of 100: this would be not a person, but something else. And for 25 million years the Baikal rift grew, and the lake itself expanded and deepened. And it will grow further. It is not simply a lake; it is a future ocean.

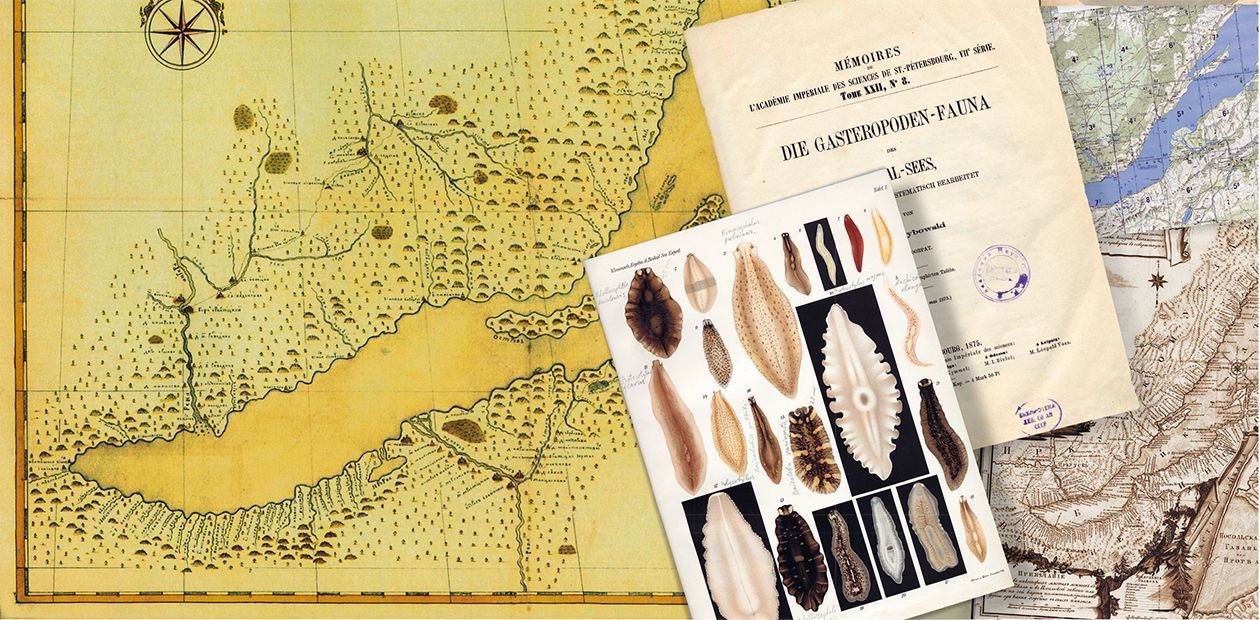

The origins of science in Russia are to be found in the work of guests of Peter I and Catherine II. The first scientists specializing in Lake Baikal were German naturalists and Russian academicians of the 18th century: Messerschmidt, Gmelin, and Georgi. Baikal omul is named Coregonus migratoris autumnalis Georgi. In the next century, the nineteenth, the rebellious Polish exiles Dybowski and Godlewski, the mysterious golomianka (oilfish) Comephorus dybowskii, the transparent crawfish macrohectopus, which Dybowski, as he himself affirmed, did not discover, but rather was discovered by his horse Ancypa… The great Russian biologists and Baikal specialists of the twentieth century: Meyer, Berg, Vereschagin, Kozhov, Taliev, Skabichevsky, in spite of all the revolutions and wars.

I remember the work of one American scientist, dedicated to the evolution of Baikal ‘species flocks’ and published in 1953. This was the year that Stalin died. The Cold War, the Iron Curtain, Russia as the enemy, McCarthyism, our struggle against ‘idolization of the West.’ There are no new works of our scientists about Baikal neither in English, nor in German. But there is an enormous review by an American scientist about the ‘Red Lake!’

What is it about Baikal that unceasingly attracts the scientists of various countries of the world? Our lake is an enormous natural ‘synchrotron,’ a model of more complicated natural systems: the world ocean, the biosphere, a place where geological processes are underway and new species form before our eyes. There are more endemics in Baikal than in all the rest of Siberia.

Let’s take as an example the Baikal seal, the nerpa. It arrived in Lake Baikal through a narrow genetic bottleneck, i.e., as a small herd, about 800,000 years ago, as revealed by our DNA sequencing data. Since that time, numerous populations of humans have conquered all of the continents. Each human population developed independently, and acquired its own kit of weapons against infectious diseases. According to common biological wisdom, without this diversity of defense mechanisms, mankind could not have survived. There are only 100,000 seals in Lake Baikal, and they can only marry their close relatives. No genetic diversity. So, how could they happily thrive through the millennia?

The eight kilometers of Baikal sediments are a continuous record of the paleoclimates of the largest continent. One must only find the correct key to it, and, perhaps, we will finally find out what will be in the future: will we all freeze to death at the onset of a new ice age, or will we burn up from global warming?

Why did the lady geologist come here from Australia, as if from a distant world? It turns out that she is studying the rift along which the split between Antarctica and Australia took place many tens of millions of years ago. And our rift is currently growing.

An international team of physicists from California, Hawaii, Canada, Switzerland, and New Zealand is interested in the ventilation mechanism of the deep waters of Lake Baikal. In Lake Baikal the water is fresh; there are no gradients of salinity, which are characteristic of ocean water. Therefore, it is easier to study the fundamental problems of hydrodynamics here.

And what about the question of gas hydrates? Bottom sediments of the oceans store enormous quantities of methane, buried as gas hydrates, a solid substance which is only stable at low temperatures and high pressures, i.e., at great depths. It is the presently inaccessible fuel of the future. So, why did Indian scientists, unaccustomed to the cold, come to us in the middle of winter? It turns out that in the warm, deep Indian Ocean, it is practically impossible to lift hydrates from the bottom. They melt on the way up. Here, on the other hand, we can acquire them at any time of the year, although it is more convenient to base equipment on the ice. Unexpectedly, the Indians met colleagues from Belgium and Japan, who also study gas hydrates…

Thanks to the enormous volume, slow rate of water exchange (400 years), and good vertical mixing, Lake Baikal’s waters have a surprisingly constant major ion content, and can serve as a natural standard for ensuring the unity of hydrochemical measurements, like the famous meter bar in Paris, or rather more like a laser standard for measuring distance. As the ancients said, it is impossible to enter the same river twice. It is possible to enter the same water in Lake Baikal many times: it will not change even in 100 years.

Baikal is very suitable for young oceanoligists to study. Scientific marine expeditions last a long time and are very expensive. The students mostly eat, sleep, and wait admission into the experiment. Here it is possible to learn oceanology more quickly and less expensively. Several international schools have already been held. Everything is done the same way as in the ocean: the collection of water and sediment samples, the measurement of temperature and electrical conductivity, geophysics, the collection of biological specimens. It is not necessary to wait: one can return home by land directly from the ‘station.’

I was lucky. I came to Lake Baikal in 1987, when the fall of the iron curtain opened the lake for international science. With this favorable wind we successfully survived the storm of perestroika, saved our face, and even became stronger.

Limnology

I have been the director of the Limnological Institute of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences for sixteen years. There are various institutes in the Academy. The majority of them are conglomerates, confederations of laboratories. Let’s take a typical chemical institute. Each laboratory in it studies the chemistry of a certain class of compounds, under the leadership of a reputed scientist specializing in this area. The integration of the institute manifests itself in the common technical basis: instruments, analytical methods, libraries, databases. If a laboratory from such an institute is transferred to another place, there will be no great calamity, since it is practically self-reliant.

Interdisciplinary institutes are another matter. Here the laboratories have to work together to solve a common problem, employing the methods of various disciplines: mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology. For example, the creation of a new catalyst, the construction of an atomic bomb, or the quest for new knowledge about the world ocean.

Not everyone knows what limnology is. It is simply the science about lakes (in Latin limnos means ‘lake’). The goal of limnological institutes is to study various lakes, usually young and small ones — such are the overwhelming majority — in order to solve practical problems: how to protect a lake from pollution, raise the yield of fish, provide water utilities, etc. Our lake is the largest in the world, and our limnological institute is also the largest in the world, consisting of 340 people. But in reality our institute is a miniature oceanological institute.

Nature does not know the borders between scientific disciplines. The chemistry of the waters of Lake Baikal cannot be understood without knowledge of physics, in particular, the mechanisms of deep water ventilation and the exchange of substances with the atmosphere. It is likewise impossible to get by without biology, since massive quantities of many substances are changed by aquatic organisms. And how can the origins of the famous endemic species be understood without knowledge of all the details about past changes of climate, water chemistry, the morphology of the Baikal depression? Why are there not one but two golomyanka fish, one large and one small, that otherwise have a very similar appearance and lifestyle? Perhaps at one time the lake consisted of two separate depressions? This is neither physics, nor chemistry, nor biology. It is natural science.

Ideally, each of our laboratories should be assigned a specific area of knowledge: hydrophysics, hydrobiology, hydrochemistry. Each should understand the language of its discipline, implement modern methods, and, most importantly, be responsible for the quality of the data it produces. The biologist cannot judge whether or not the physicist made his measurements correctly, and the physicist cannot decide whether or not the biologist correctly identified species. Each problem must be solved collectively. How can quality be controlled?

Fortunately, various natural sciences use the same methodology. The solution of any problem involves a number of standard stages that ensure professionalism. For example, it is necessary to prove that no one has solved the problem yet.

My classmate Sergei Kara-Murza taught me a very simple approach. Is a scientific publication worth reading? Look at the title first, and immediately afterwards look at the list of cited works. If a Russian-language publication contains references only to Russian works and translated works by foreign authors that were written thirty years ago, then one can save time and skip the article. Of course, it is possible to miss a discovery made by a home-grown genius, but the chances of this happening are extremely small. In any case, the author of the article could not have a clue about the contemporary state of his science. Such a scientist has no place in an interdisciplinary team.

The second simple criterion is the estimation of a scientist’s rating. In Russia this matter has always been poorly understood, and not only in science. We are collectivists. We are convinced that there are no irreplaceable people. Each individual is no worse than Bill Gates. If you achieved some kind of success, then you should be careful. It is dangerous to stand out. A scientist’s success is measured not by his salary, but by his rating. Can we entrust a scientist with a grant, i.e., the taxpayers’ money? In my opinion, the position of leader can be bestowed only upon a person who previously achieved success. Let the others continue to execute the plans of others for now.

It is now very simple to find out how many times in your life you have been quoted: there is the Internet-accessible Web of Science. If you want to find out who is looking for work at Lake Baikal: a scientist, a charlatan, or maybe a spy — just spend about 15 minutes at the computer. Recently Nobel laureate Zinkernagel was here. His rating is 11,000 references! The rating of a typical natural scientist belonging to the Russian Academy of Sciences is a few hundred references. It is also easy to exclude ‘environmentalists.’ For example, a certain scientist angrily protested against the discharge of phosphorous into Lake Baikal. In the Web of Science we found that throughout his entire life, he was only cited once. Somebody cited a paper he wrote about the behavior of squirrels. Nothing about phosphorous.

A director today does not need much brains in order to objectively evaluate the level of potential partners. But this is not enough. He still has to know ‘a little about a lot.’ It is a long way to such a level of knowledge. One must start in childhood.

A Little About A Lot

I deeply respect scientists that know ‘a lot about a little.’ Such people work on the very frontier of knowledge, and create radically new knowledge. They select their tasks themselves. There is nothing more difficult than such work. In order to achieve success, one must literally be a fanatic, and not become distracted for even a minute. But even this is not enough. A special kind of talent is necessary, and so is luck. Such scientists sometimes receive the Nobel Prize, and they deserve it. But more often they become recognized only several years after they die.

In the 18th century, natural scientists were not afraid to cross the borders between branches of knowledge. And in modern science, none of the greatest breakthroughs have been made by narrow specialists; for example, Darwin’s theory of the origin of species, Vernadsky’s teachings about the biosphere, or Watson and Creek’s double helix. However, the recipe is not as simple as ‘cross borders, and you will become great.’ There is only a single step between the great and the foolish. Nothing is funnier than an ignorant person who is certain that he knows ‘a lot about a lot.’

What, then, should we do? Lake Baikal needs to be studied now, and we even receive a salary for it, but our great polymath is missing. There is only one way out: the integration of professionals. The famous ‘sigma’ logo of the Siberian Branch.

At the minimum, the director of an interdisciplinary institute should know a little about a lot. As for me, I like my job as the director of the Limnological Institute. It is not like playing the violin, piano, or percussion; it is like conducting an orchestra. The conductor does not have to be able to replace the violinist or pianist. His job is to work with people. Not everyone likes such work, but I do. I confess that there is no greater pleasure for me than to unite people from various countries, various sciences, with various methods and even with various goals into a single joint scientific expedition. Often this is done literally on the day before the expedition sets out. Domestic preparations must be made: one must know for certain which ‘hyper-problems’ must be solved, and which can be solved with the available tools.

I do not exactly know how to become a conductor. It seems like a simple job: you simply wave your hands. Certain politicians have tried it. It’s probably not enough to wave your hands; it is also necessary that the musicians in the orchestra follow your directions not only during the concert, but during rehearsal as well. So, you must know how to read music and play at least one instrument. In order to get such a job, you probably also need to have a degree and documents. And in order to attract audiences you need a reputation, or rating.

When V. A. Koptyug invited me to Lake Baikal, I had both the necessary documents and a rating. I had graduated from the chemistry department at Moscow State University, I worked in Moscow, then in Novosibirsk, defended first my Ph.D., then doctoral theses, received a State Award, headed an ultramicrobiochemical laboratory in the Novosibirsk Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry.

I even knew a little about a lot. In my case this might not be a merit, since I mostly knew about things that had nothing to do with my profession. I simply received such genes, and my personal history turned out in such a way.

My father was a ship-repairing engineer. In 1944 my mother and I went to Vladivostok, and from there we crossed the Pacific Ocean, and joined him in America, where he has working as an all-around specialist. He repaired Russian ships that brought military cargo by land-lease, bought oil, was a ‘red merchant:’ selling canned Kamchatka crabmeat, Palekh lacquered boxes, and Fedoskino decorated tin trays to Americans. He never told me why he received the decoration of the Order of the Red Banner in 1949, when we returned home. I suspect it was not for selling crabmeat. He organized receptions on behalf of famous Russian visitors to America on Russian ships. It is difficult to believe how long ago this was, but I once shook hands with Charlie Chaplin, a guest of Konstantin Simonov on our steamship. The main lessons I learned from my father were: do everything without looking back; do both your own tasks and those that are not necessarily yours; don’t make a fuss about things; and most of all: don’t be afraid to take responsibility. And the cost of a mistake in those days could be one’s freedom or even one’s life — much higher than today.

We traveled by sea both to America in 1944 and to Odessa in 1949. There were no other children among the passengers. The captains, mechanics, and boatswains all spoiled me. I crawled all over both ships from the bridge to the machine department. To this day I adore ship engines and the smell of diesel fuel. This way I found out a few things about the sea. Who would have thought that I would be responsible for an entire fleet of research vessels on Lake Baikal?

After three months in the States I spoke English fluently. In the first grade class the boys made trucks by themselves: they sawed out pieces of wood, fitted them together with nails, and painted them. And the girls prepared small, but real dinners. At that time, America was an interesting place, a country of inventors and engineers, in which respect for handicrafts was nurtured from childhood.

In Moscow, in the seventh grade I became interested in chemistry and therefore taught myself glass-blowing. I could make almost any small glass object: an ampoule, a T-pipe, a retort, a Liebich’s condenser, a Dewar flask. This turned out to be very useful for my career. In 2003, when my membership in the Russian Academy of Sciences was being voted on, my schoolmate, academician Evgeny Sverdlov, standing at the rostrum, reminded the members of the Branch “You must choose Michael. Remember, which one of you didn’t receive a glass sprayer from him?”

My life would undoubtedly have turned out differently if I did not acquire mastery of the English language in childhood, if I did not study in the first special Moscow English School, where I was taught, in addition to the English language, English literature, geography, anatomy, and electronics — all in English. Even the Belarusian partisans in the theater group spoke English. After finishing the university I worked in the Translation Bureau in order to make extra money. The system was rigid: they typically gave about ten days for a large article. I ended up learning a little about a lot of things: about plastics, about the separation of uranium isotopes, about the histochemistry of enzymes, about the purification of waste water.

My first scientific publication “On the synthesis of β-chlorovinylketone,” written during my third undergraduate year at Moscow State University, was also the result of my familiarity with a little about a lot. This ketone, which the laboratory workers needed, was considered impossible to ‘cook’ in quantities greater than 200 grams. I successfully ‘cooked’ a whole five kilograms of it. For this, I had the workshops of the chemistry department make a special metal reactor. My mother’s favorite enameled kitchen pot, brought from America, became the main part of the reactor (alas, without her knowledge). I found out a little about the work of a designer, a turner, a milling-machine operator, and even a blacksmith.

My way from Moscow to Lake Baikal lay across the Novosibirsk Academgorodok. What could attract me there in 1965 so much that I decided to give up the famous Institute for the Chemistry of Natural Products and life in the capital for obscurity? My colleagues simply did not understand: how can one leave Moscow and go to some kind of backwoods ‘where bears roam the streets?’

There were three factors influencing this decision. The first was human: Lev Stepanovich Sandakhchiev, at that time a brilliant young scientist (now a member of the Russian Academy of Science and director of the Vector Research Center in Novosibirsk). He lured me there with interesting work. The second factor was subjective. They had promised not to exploit me for translating scientific articles into English. This unpaid labor had become quite tiresome for me in Moscow… The third factor was the very infrastructure of the Novosibirsk Institute of Organic Chemistry. In the pilot plants it was possible to experiment with reactors of up to ten tons in capacity, instead of 1-liter units. The Design Bureau. Wonderful mechanical workshops. The radioelectronic group. A glass- and quartz-blowing workshop. In general, such pilot facilities were the norm for the Novosibirsk Academgorodok. The founders, Lavrentiev, Budker, Vorozhtsov, Nikolaev, and Boreskov, fairly considered that without pilot facilities it is impossible to put anything new into practice. In Moscow, in the Academy of Sciences, there was nothing on such a scale as this. Here I found out what are technological regulations, design documentation, and standards inspections.

In the Novosibirsk workshops I became interested in the production of pilot groups of small scientific instruments for bioorganic chemistry: micropumps, micropipettes, and later, devices for chromatography and electrophoresis. In Moscow, such equipment was bought from importers for foreign currency, something that we could not even dream of doing in Novosibirsk. But there was enough homemade equipment there for everyone, and we even sent some of it back to Moscow.

The Milichrom

I think that V. A. Koptyug chose me for two reasons. Two years before, I had told him that I was ready, if necessary, to go anywhere in order to try myself at independent work. Second of all, the time had come to implement modern instruments and methods in the protection of Lake Baikal. V. A. Koptyug knew well and always eagerly supported our milichrom-building industry.

In 1969 L. S. Sandakhchiev, having successfully defended his dissertation, began a new project. By education, he was a specialist in the chemistry of polymers, and by work experience he was a bioorganic chemist. He had decided — in the middle of Asia — to study the biology of the individual development of the single-celled Mediterranean alga Acetabularia mediterrania. He began the new work with his usual broad sweep. It is difficult to believe, but he even had cisterns of seawater brought from Vladivostok. It is hardly imaginable that contemporary scientific bureaucrats — not only Russian, but foreign as well — would allow such work. They only care about ‘innovations,’ ‘market demand,’ ‘result-oriented budgeting,’ and the Acetabularia is not sold on the market — it’s just too small.

By the way, it is an extremely interesting organism. It consists of a single cell of up to five centimeters in length. The nucleus is at one end, in the rhizoid, or ‘root.’ At the other end grows a surprisingly beautiful umbrella. The nucleus, along with all of the genome DNA, can be cut out, and, if you tie up the stem with a thread, so that the cytoplasm won’t leak out, the cell, deprived of its nucleus, will still grow a beautiful umbrella several months later. What, then, are we to do with the basic dogma of modern biology, according to which all information about the structure of an organism is contained in the nucleus, in the DNA? Here there is no nucleus at all!

In order to cope with this problem, Lev Sandakhchiev had to learn how to carry out manipulations of substances formed by a single cell, and especially with nucleic acids: how to isolate and purify them, how to analyze their structure. All this he did 30 years before the birth of the famous lamb Dolly. Under his direction, our excellent workshops made dozens of micromanipulators, microsyringes, and microfurnaces in a very short time, and, finally, the first microspectrophotometer, the grandfather of the Milichrom.

Sandakhchiev was interested in many things, for example, such extremes as speleology, the study of caves. One of his interests was the card game Preference. Fate brought him behind a card table together with Sergei Vladimirovich Kuzmin, a genius optician and designer, laureate of the USSR State Award and dissident, at that time a senior laboratory technician at the neighboring Institute of Thermophysics without any higher education and a salary of 70 rubles per month, and dreaming of becoming the world champion in bicycle racing. In order to win a bet, Sergei promised to make an ultraviolet microspectrophotometer, which would be capable of seeing DNA in a single Acetabularia cell. Four months later the instrument was ready. DNA chromatography at that time was carried out on 10—12 milliliter columns. The volume of an ordinary spectrophotometer is 3 milliliters. Using Kuzmin’s device, Sandakhchiev was able immediately to carry out chromatography on a 1 microliter column. Thus the scales of DNA spectrophotometry was reduced to 10,000 times less than that of the rest of the world.

I did not take part in this. I only observed ecstatically. And, of course, I immediately wanted to apply this new method to ordinary, i.e., not unicellular, biochemistry, in which I was then involved. The workshops quickly manufactured a second such device. A year later, I and my colleague, Sasha Girshovich, sent out the first publication about the data collected through this device to the international journal BBA. They didn’t take it. The reviewer had gotten to the root of the matter: he simply wrote “it’s impossible to work on such a scale.”

And he was right. Once, Sasha and I spent a couple of days working on the problem. Nothing came out of it. The reason turned out to be simple: the chromatographic microcolumn had to be placed deep within the device, and solvent had to be injected blindly. The column was so small that we simply lost it, and injected the solvent into the device without realizing that there was no column inside.

For ordinary biochemistry, in order to obviate the micromanipulator, we expanded the device’s scale by ten times, and we still achieved a sensitivity level 1,000 times greater than what the rest of the world was capable of. Then we gave it to the biochemists. By the beginning of the 1990s Russia had manufactured 6,000 Milichroms, great-grandchildren of the first microspectrophotometer, for a multitude of disciplines: science, forensics, pharmaceuticals, environmental protection, etc. During the perestroika years, a private company in ‘poor Russia’ managed to manufacture and sell about 100 A-02 Milichroms, assembled from components made in various parts of the world, but still based on S. V. Kuzmin’s original microspectrophotometer, for $30,000 each. Why? The answer is simple: in a commercial laboratory, the use of this instrument covers the initial cost within a year after purchase.

The Swedish firm LKB, then the world leader in scientific instrumentation, bought the license to use Kuzmin’s invention. My knowledge of English and the genes of my ‘red merchant’ father came in handy. Under the leadership of the Russian foreign trade agency LICENSINTORG, I passed a useful school of international trade in intellectual property. Later, this turned out to be very useful at Lake Baikal. We received $60,000 dollars and a wonderful Swiss milling machine, at which I later spent many months manufacturing new accessories for the Milichrom.

These days, people dream a lot about ‘innovation.’ Managers understand three things poorly. First of all, innovation requires crazy ideas, for example, growing a Mediterranean alga in the middle of Siberia. Second of all, talent is needed, and, better still, genius, which does not promise, but makes a workable object. As a rule, talented people and geniuses are very inconvenient and difficult to manage. However difficult it may be, one must tolerate them. Thirdly, the risk of failure is very high, and much time is needed before application — usually about 10 years. But a single Milichrom covers the expenses of dozens of academic laboratories. Geniuses do not appear in a building simply because it has a sign that says “Technopark.”

V. A. Koptyug calculated that the Milichrom could be implemented at Lake Baikal. And he was right. Unfortunately, S. V. Kuzmin didn’t come to Baikal — he died in 1986.

Scientific Paratroopers

The move from Moscow to Novosibirsk in 1965 was very useful, and not for me alone, I think. It is well known that a person, especially a young person, needs to change his work once every several years. It’s just like growing corn: a first generation hybrid will give a large harvest if you only use fertilizer. It’s the effect of heterosis. In Novosibirsk I found what I was looking for: the freedom of scientific inquiry, a harmonious combination of basic science and experimental production. I think that the laboratory also benefited. It was headed by D. G. Knorre, presently a member of the Academy of Sciences, the founder of the largest Russian bioorganic chemistry school. Here my experience and knowledge of traditions that I had acquired in Moscow from my teacher, Academy member N. K Kochetkov, the founder of the Russian bioorganic chemistry, came in handy.

The same thing happened again 22 years later at Lake Baikal. The difference is that I came here not by myself, but with a group of 20 ‘scientific paratroopers:’ young, ripe specialists, mainly ‘new biologists.’ It is interesting that all of them soon acquired a place to live thanks to a decision of the Irkutsk Regional Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The goal of the expedition was to implement new methods.

The collective that we joined was very dedicated to science — low-paid and heroic. The leader was Professor G. I. Galazy, an uncompromising defender of Lake Baikal. Many good things were done under his auspices. The most important was that he created a real scientific fleet, and built buildings in Listvyanka and Irkutsk. The problem was that the government demanded exact quantitative information about the state of Lake Baikal, and the institute could not procure such information, because it had neither the necessary specialists, nor the necessary instruments. Anyway, what’s the point in hiding one’s sins? — For the sake of the defense of Lake Baikal, we sometimes spread ‘horror stories’ based on unconfirmed information. However, the overwhelming majority of the collective did not participate in such ‘political chemistry.’

Now is probably the time to tell about my position. I am not a politician, and do not like politicians. In order to realize his ideas, a politician is simply compelled to deceive the people. If the ideas are clear to the people, then why do we need a new politician with all his charisma? And what are the chances of a politician being elected if he readily announces that he will take the people along a difficult path without the guarantee of success? Not to speak of military machinations, and the deception of political opponents and foreign enemies. It’s also possible to sympathize with politicians. Their profession is to make decisions in spite of insufficient information. There is not enough time to gather enough information. If there was time, politicians would not be needed. Scientists would figure everything out and then say what needs to be done. The problem is that scientists cannot agree with each other. However unpleasant politicians may be for me, I still understand that mankind can not get by without them.

The great merit of the old Baikal specialists was that they did not allow the industrialization of the lake. There were people that wanted to build here not one, but thirty industrial complexes. Like G. I. Galazy, I honestly consider that there is no place on Lake Baikal for the Baikal Pulp and Paper Plant. But why does everyone speak exclusively about water pollution? What about the air? One can smell mercaptan from 10 kilometers away. What about the industrial landscape? Is there really so little space in Siberia? N. S. Khrushchev’s decision to build the Baikal Pulp and Paper Plant brought an incalculable moral harm to Russia.

G. I. Galazy was absolutely correct when he protested against the Soviet (and Russian) principle for the preservation of bodies of water: the notorious MPCs — maximum permissible concentrations. In connection with their establishment, we must find an answer to the question: exactly how much garbage can be poured into Lake Baikal before it starts to do harm? The State Planning Committee demanded “Give us exact figures, and then we’ll take care of the location of industry ourselves — it’s not your business, comrade scientists.”

But the volume of Baikal is immense. The MPCs are a direct road to its unhindered pollution. What can we do if today we don’t see certain types of pollution because our methods aren’t capable of detecting them, and we only find out about them 50 years later, and their results have irreversible consequences? Lake Baikal is not a pond. You can’t just pour out its water somewhere, and add new water. In industrially developed countries such as the USA, Germany, Scandinavia, ecological MPCs have never been applied. There they operate according to a pragmatic principle: constant, planned reduction of waste discharges, forcing industry by economic methods to adopt new conservation technologies. Russia, as always, goes on its own path.

The first urgent job that we had to do at Lake Baikal was the creation and confirmation of standards of permissible impact on the Lake Baikal ecosystem. With the support of V. A. Koptyug, we were able to abandon the MPC principle and apply the idea of transfer to new technologies and the idea of landscape preservation. Much of this remains on paper, but some of it has been realized. For example, in 1990, the Selenginsk Pulp and Paper Plant was the first in the world to implement waste-free technology, and since then it has produced no industrial waste water. If we had continued this way, we could have had waste-free, non-polluting industrial production in Baikalsk. Then the only problem that would remain would have been the landscape issue, but it would be possible to wait a little while to solve it — there are already enough other anthropogenically disfigured landscapes around Lake Baikal.

It immediately became clear that a national law for the protection of Lake Baikal was needed. It was also necessary to add Lake Baikal to the list of World Natural Heritage Sites. Today, both of these problems have been formally solved, although in reality these legal acts have no effect — there is no political will.

The Customs Office As A Doer Of Good

It was necessary to acquire comprehensive information about the condition of Lake Baikal as quickly as possible. Both our new methods and international science helped us in this endeavor. At the First Vereshchagin Scientific Conference in 1988, the Siberian Branch, with the support of V. A. Koptyug, announced its intention to create a Baikal International Center for Ecological Research (BICER), in which scientists of all countries, together with Russian scientists, would be able to study all aspects of Lake Baikal. The center officially opened later, I think, in 1990, but began working earlier. A real gold rush began. During the past few years about 2,000 foreign scientists, engineers, and students have spent time at Lake Baikal, and not at symposia, but in real scientific expeditions. They brought unique, often heavy equipment. At first, romanticism played an important role: many, it turns out, had dreamt about visiting Lake Baikal their entire lives. Afterwards, economics became more important: it was possible to organize a candlelit banquet for six people in a Moscow restaurant for six dollars, and scientific expeditions were fabulously cheap.

There used to be three customs officers in Irkutsk. Now there are 3,000. I remember that once two containers with very heavy geophysical equipment arrived from America at around 8:00 PM. The customs officer who had the stamp was already at home. The other customs officer gave the telephone number and address of the first, who was glad to help, came with us to the station, stamped the cargo, and let it through. At night we loaded it onto a ship, and in the morning we set out on an expedition. There were many curious occasions, and there were many serious ones, too.

My meager experience in foreign trade and knowledge of a little about a lot came in handy... I often had to quickly jot down memoranda about expedition plans and mutual obligations, unite physicists with biologists, Japanese with Belgians, Americans with Germans, and all foreigners with Russians from many of our scientific centers. The ‘new biologists’ from the paratroops decoded the chronology of the appearance of Baikal endemics. The Irkustsk school of paleoclimate specialists came into being... In 1988, 15 citations with the keyword ‘Baikal’ were registered in the Web of Science. Since the end of the 1990s 120—150 citations are registered per year.

It would be wrong to say that Russian science at Lake Baikal before this was bad. It was certainly not. But it was little-known in the world, and it was little-known even in Russia itself. Now the situation has radically changed: we are known in the world, and our scientists know firsthand what’s going on in the world. We have learned many things, and in our turn we have taught many. The most important thing is that an explosion literally occurred in the acquisition of exact knowledge about the lake.

International science has confessed that Lake Baikal’s purity is close to primordial, excluding a few small polluted areas. It is always possible to express doubt in relation to domestic Russian science: it could reflect the opinion of various influential political interests. But, probably, only an insane person could suspect a conspiracy of hundreds of scientists in 20 countries of the world. On the basis of the opinion of international science, UNESCO agreed to Russia’s proposal to add Lake Baikal to the list of World Natural Heritage Sites. Places that have undergone irreversible anthropogenic changes are not included in this list.

Besides purely scientific, there were also many ‘semi-scientific’ projects, for example, expeditions made by National Geographic magazine, Jacques Cousteau, and Japanese television.

By now, the gold rush is over, and has been replaced by an ongoing process of ordinary scientific cooperation. There are less sensations, less banal curiosity, and more serious work aimed at the solution of fundamental scientific questions, for example, problems of evolution, problems of paleoclimates, the aforementioned gas hydrate problem, ‘barrier zone’ problems, problems of the biogeochemical silicon cycle. We have expensive modern instruments. Our scientists, by right, always make a contribution to joint projects at least equal to that of foreign scientists. Many of our people have used Baikal as a ‘springboard’ leading to work abroad, but every cloud has a silver lining, and their positions are opened to young scientists. We have more young people than anywhere else, over 50 %. The most important thing is that young people come here from abroad to study. So far we have not been able to provide them with anything but the most Spartan living conditions, and there are not many of them. But there must come more later. We will never fully become part of international science if foreign students will not come to Russia to study.

These days, on the lake that received an international certificate of purity, tourism is burgeoning, the winter Olympics are being held, some Dutchmen ice-skate and ride bicycles across the ice from one end of the lake to the other. It is pleasant to think that we added our contribution to this process.

International cooperation at Lake Baikal was very interesting not only in a scientific sense, but in a human one as well. Now I will tell you a most amazing story: how and why British soldiers washed their boots in Lake Baikal.

How The British Army Washed Boots In Lake Baikal

Winston Churchill considered that many things in history are determined by chance, and his goal was always to take chance under his control. We often had to take chance under our control. The most curious instance — since we have already begun speaking about Churchill — took place with British soldiers.

One fine day, the institute received a letter from a certain British army captain, an officer of the Green Howards regiment, who asked for help in organizing a trip to Baikal with his soldiers. It turns out that they have a tradition to go each year to some remote, poorly accessible place in order to train themselves and help people at the same time. The British Queen and the Russian authorities knew about this idea. They needed our help with one matter: choosing a place at Lake Baikal, preferably in the mountains. What should we offer the British? The institute doesn’t work in the mountains, and nobody knows what’s in the mountains. I offered them a most needed and heroic task: counting the Baikal nerpa under the direction of our biologists. The work must be carried out during the springtime, and consists of riding across the disintegrating icy surface of the lake on motorcycles 25—30 times, each time on the way setting up 5—10 squares, and, in each square, counting all of the nerpa holes that contain the shedded white fur of a new-born nerpa pup. Knowing the number of pups, we would extrapolate it for the entire area of Lake Baikal, and from their age and gender distribution (data that we acquired through work with hunters), find the total population. We made the last such survey several years ago, and now we have no motorcycles, and there are not enough fanatical biologists. The help of the British would definitely be useful. Furthermore, there are certainly not any military outposts on the icy surface of Lake Baikal. I wrote about all of this to the British and waited. They liked the idea. The captain came, along with an officer, and sorted out the details.

The expedition was almost ready, and the Russian authorities were not asking any questions. And all of a sudden the British ask for help with their visas. It seemed strange: wouldn’t it be easier for the Her Majesty to make an arrangement with the Russian Embassy? I called both the Russian Embassy in London and the British Embassy in Moscow. Nobody knew anything about it. They suggested asking in the Russian General Headquarters. I call. They ask me to write a letter. I write “If it’s possible, then permit it; if not, then forbid it.” They don’t answer. I call them again and write that if they don’t expressly forbid it, then I will invite the British. They still don’t answer. I give them visa support. The visas are given out, the British arrive, for some reason, from Germany on an enormous Russian airplane with a Mercedes for the director of our Regional Environmental Committee, with plastic garbage bags for our ‘greens,’ sledges, motorcycles, tents, sleeping bags, dry rations, and walkie-talkies. The customs office didn’t know about any conversations between the Queen and President Yeltsin, and they won’t let us bring the walkie-talkies and global positioning systems into the country without special permission. And the British, for safety reasons, won’t walk on the ice without these devices.

So, I got in trouble for having done something that was not within my authority. V. A. Koptyug seemed ready to hit me, but softly said “Misha, please don’t do that any more.” And he could have fired me… Eventually, everything turned out fine: the expedition took place as planned. There turned out to be many nerpa: 100,000. Somebody said that this was the first time the regular British army had been on Russian territory since the defense of Sevastopol in 1853—1856 — probably he forgot about the British intervention in the Russian Civil War in the North.

While the British lived in Listvyanka, they behaved like good soldiers: they drank, fought with the locals, and once they fought with each other. Four of the soldiers were women. I remember that they would never let anyone help them carry heavy cargo. And not long before this speaker of the Russian Parliament Vladimir Zhirinovsky had announced that the Russian army would soon wash its boots in the Indian Ocean. The Irkustsk press picked up the story: while we are still not yet ready to go to India, the British army is already washing its boots in our Lake Baikal… Now it seems funny, but at that time it was a source of stress.

Why Should One Become A Member Of The Academy?

When I went to Irkutsk, V. A. Koptyug decided that I should become a Corresponding Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, so that the bureaucrats would have to deal with me. At first this official title helped: it was considered rude not to answer a telephone call, especially by ‘hotline’ (from my boss’s Moscow office) from a Corresponding Member. Later, many new ‘academies’ appeared, and Corresponding Members were no longer valued.

Many years later, last year, I was chosen to become a Member of the Academy. Why? See above: it’s the glass sprayers.

People often ask me “What does this new title do for you?” Many, especially young scientists, honestly believe that such titles are unnecessary and even funny. I don’t think so. This tradition goes back to the Stone Age. Having killed the tiger, the leader hung one of its teeth on his neck, and then everyone would obey him. It was not necessary to kill a new one before every new military campaign. It’s the same way with military stripes — they’re just convenient. And truly, new bureaucrats sometimes will talk to a member of the Academy, and this way questions can be solved. What else are the new ‘epaulettes’ good for?

Do I feel like a ‘Member?’ To be honest, I feel not like a Member, but rather a soldier, recruited for work at Lake Baikal. I do not have my own laboratory at the institute these days. A scientist, no doubt, must work in live science, but with this there is always a conflict of interests. How can I refuse support to my dear self?

Life is more complicated than plans. I had no choice but to lead a paleolimnology laboratory for several years. Now, through a Presidium of the Russian Academy of Sciences program, I have become involved in the molecular biology of silicon, but this is still not a laboratory, but a project. I try to do this without causing harm to the whole.

And time is passing. The saddest part of the life of an old member of the Academy, a truly old person, is that, without being aware of it, he loses the ability to critically evaluate his own thoughts. People obey him by inertia, but sometimes scoundrels take advantage of him.

How can one prove to oneself that he is still capable of work? Very simple. In business, people are not driven out because of their age: as long as you make money, then you’re useful. Nobody pays money in vain.

I don’t know if it will work, but I made it my chief goal for the near future to prove the practical usefulness of the institute under market economy conditions; that is, in short, to make money.

For many years, the basic paradigm for the preservation of Lake Baikal was negative: don’t do this, don’t do that. In my opinion, a change of key is needed: we need to find a way of raising the productive forces of the Baikal region, while strictly obeying the law on the preservation of Lake Baikal and the principles of World Heritage. I follow the example of the famous geochemist Fersman: he created an academic commission on the development of Russia’s productive forces together with his colleagues during the First World War, and it continued to work successfully during Soviet times.

What do we need to develop in order to double the GNP? In Buriatia, perhaps, it needs to be tripled: it is a depressed region.

The possibilities of science are immense. We have already partially realized one project: the production of bottled Baikal drinking water. It has long been known that Lake Baikal is the well of the planet, a priceless store of fresh water of global significance.

At the beginning of the 1990s, the president of a Japanese bank came to Lake Baikal and asked for a sample of water from the lake. Why? It turned out that he wanted to produce bottled Baikal drinking water. I thought “where should we take the sample from? At the source of the river Angara, at the surface?” We needed somehow to avoid humiliation: there is a town there, and it would be easy to catch some kind of germs. We gave him some water from the depths, and it turned out to be excellent. This is how the idea to produce water from the depths emerged.

We patented the idea, and produced an experimental batch using a pipe that they lowered from the ice to a depth of 400 meters. We developed the technology of finish purification, sterilization, and an entire complex of methods of analysis and quality control. The organizer was A. N. Suturin, a geochemist and one of our leading scientists.

Russian limnologists had long known that the purest water in Lake Baikal is found in its core, at depths between 300 meters below the surface and 50—100 meters above the bottom. This has been confirmed by foreign scientists, who measured the age of the depth waters. They answered the question: when was a certain portion of the water at the surface? It turned out that the age of the water near the bottom was 8—10 years, while the water in the core can be up to 16 years old. This is explained by a unique method of water ventilation: part of the surface water of Lake Baikal immediately goes down to the bottom, passing through the core. As a result, organisms living in Lake Baikal — mostly microbes — are able to purify the core water longer than anywhere else. In general, that’s why it is the purest.

The next question was: who will buy and drink our bottled water? It was clear to everyone that Russians would not: why should they pay for such water when it flows from the faucet? Life proved our ‘scientific’ prognoses to be wrong. In 2003, Russians drank two billion liters of bottled water, including 50 million bottles of Baikal water.Of course, this is very little. But all the same, those 50 million bottles produced a turnover of $20 million. $8 million was spent on taxes alone, equal to eight times the institute’s annual budget. Nothing is stopping us from establishing a production of 2 billion bottles per year — a yearly turnover of $800 million. That’s $400 per year for each person living in the Baikal region. Not a bad contribution to the GNP. And this will happen, sooner or later. The sooner, the better. If everybody on Earth drank one and a half liters per day of the water stored in Lake Baikal, there would be enough for everyone for 6000 years. It is a practically inexhaustible resource. There is no damage done to the lake.

There is a time to throw rocks about, and there is a time to gather them. Our first duty today is to remove the unfounded limitations on people’s activity in Lake Baikal. For example, recently the government, acting on a suggestion from ichthyologists from Ulan-Ude and naturalists from Moscow, adopted a resolution on the impermissibility of changing Lake Baikal’s level in the interests of the work of the Angara Cascade Hydroelectric Station beyond the range of 456—457 meters above sea level. The goal of the developers of this prohibition was entirely mercantile: to force the Irkutsk power engineers to pay for the ‘environmental damage’ if they violate the prohibition. The fact that it is technically impossible to observe this rule does not bother anyone. The engineers need a range of not one, but one and a half meters, in order to accumulate water when there is relatively less water, and slowly lower it in times of abundance without damaging objects located downstream from the Irkutsk Hydroelectric Station. The cost of the issue is 1.5 billion rubles just from the decrease in energy output. Half a meter of the lake’s level is equal to 15 cubic kilometers, a quarter of the annual flow of the river Angara. They say that last year the water bureaucrats were asked to approve the reduction of the lake’s level by 1.5 centimeters. They didn’t allow it, and the delivery of goods to the north was almost cut off. It’s a good thing that it started raining at that time.

Our expert commission unambiguously showed that the regulation of Lake Baikal’s level by power engineers has not caused any harm to the ecosystem. The population of omul not only did not decrease, as ichthyologists, i.e., the authors of the prohibition, had predicted; our directs sonar calculations showed that between 1995 and 2003 the omul biomass did not decrease, but grew from 20,000 to 50,000—70,000 tons. A difference of 30,000 tons of omul at a market price of 60 rubles per kilogram is worth 1.8 billion rubles. Omul should be caught, because otherwise it dies without purpose. The entire annual budget of the Limnological Institute is about 40 million rubles. The budget of Buriatia is about 2 billion rubles. Do the math yourself.

Could science become an immediate productive force, as they used to say? Sometimes it can. Last year it was decided to electrify the island of Olkhon. It is an important task: what kind of life can you have without electricity? What kind of international tourism? Furthermore, women complain: they can’t iron their dresses, there’s nowhere to plug in an electric iron, and the antique irons that use coal are no longer produced. It was decided to lay an underwater power cable to Olkhon. This is correct: an above-ground cable across the strait would not improve the landscape. Furthermore, the legendary Sarma wind blows across the strait, and the construction of a power line that could withstand a hurricane is expensive. Over many years of research, we accumulated a mass of information about the Small Sea. We have a fleet, geologists, and underwater biologists. We have connections with Russian geophysicists. Under the contract with the power engineers, we are studying the possible routes for laying the power cable and are giving recommendations about how to do this reliably and inexpensively.

For example, mysterious sand banks, about one meter in height and 20 meters apart, were discovered at the bottom of the strait. For the sake of the safety of the cable, it is extremely important to find out how they came about. One possibility is that they are waves of ripples from the current in the strait. If the current is the cause, then their speed is very high, and they are dangerous for the cable. Another possibility is that the banks are former dunes that became submerged in the lake. 18,000 years ago, during the last ice age, the climate was dry, the river Selenga dried out, the level of Lake Baikal diminished by about 30 meters, the sandy bottom was exposed, a strong wind blew, and dunes formed. 15,000 years ago, the climate became more humid, the level slowly rose, and the dunes were flooded. In that case, there is no danger for the cable, since the next time the lake’s level diminishes by 30 meters will not be soon. There is no final answer to this question yet, and another dozen possible explanations could be invented. Only one thing is clear: even paleolimnology can become an immediate productive force! Given that we own the fleet, we have not ruled out the possible participation of the institute in the laying of the cable.

There are many ideas. There’s not enough time to tell about all of them. I’ll tell you just one more. To the northwest of Lake Baikal, the famous Kovykta gas deposit is being prepared for exploitation. A program of gas delivery to the Irkutsk region is currently being realized. But sooner or later, it will be necessary to step up exports. Planners, intimidated by environmentalists, are examining only such routes that avoid Lake Baikal by many kilometers. Why? Gas is not oil, and it could not pollute the water of Lake Baikal, even in the case of the bursting of a land gas pipeline. What’s more is that the sediments of Lake Baikal contain enormous quantities of gas hydrates, which constantly let methane into the water. There are other methane outlets in the Lake which are not connected with hydrates, especially near the Selenga River delta. Why not lay a pipeline the short way: along the bottom of Lake Baikal, as is done in the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea? If the pipe breaks, a gas bubble will escape into the atmosphere, and there will be no damage to the lake itself, since there is already a large quantity of methane dissolved in its water, and all of the endemic species are used to it. However, it is possible to lay an export pipeline across Ulan-Ude, across other industrial centers of Buriatia, and provide it with ecologically pure fuel. Here we don’t need to speak about the GNP: everything is clear already. The idea is debatable, but it deserves investigation.

Would anybody listen to me if I was not a member of the Academy?