In Search for Treasures of Hero Khara-Jia-Jun. Unpublished Works of S.I. Rudenko

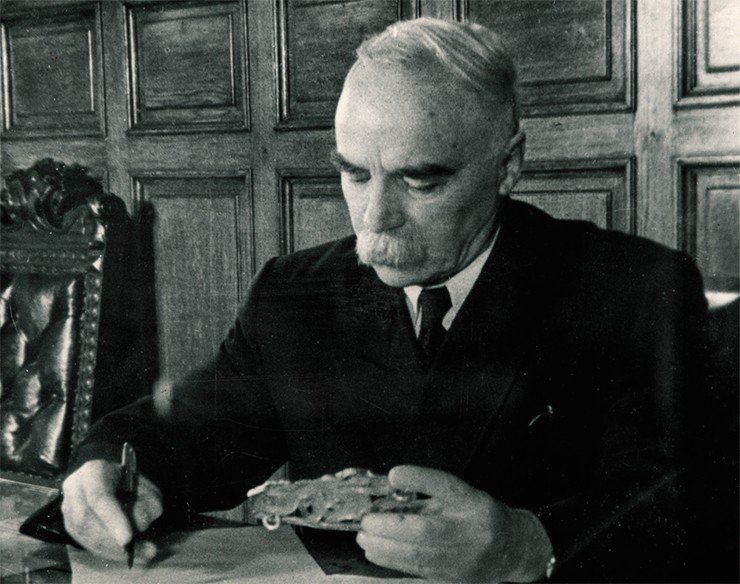

The name of Sergei I. Rudenko, a great archaeologist of the 20th century, a discoverer of the famous Pazyryk Mounds, is well-known to all specialists in the ancient history of Siberia and Far East. The St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of the Russian Academy of Science (RAS) has some unpublished monographs of the scientist. One of these monographs is devoted to the Dead City of the ancient Tangut Empire...

Sergei I. Rudenko was an archaeologist, anthropologist, ethnographer, culturologist, historian, holder of master’s degree in geography, and doctor of technical sciences. He is the author of about twenty investigations in general and engineering hydrology. His life was long and not easy. He was born in Kharkov, but spent his childhood in the Ural region, where he got interested in the material and spiritual culture of the region’s native Bashkir population.

Having left the gymnasium in the city of Perm, Rudenko became a student of the physical-mathematical faculty of St. Petersburg University. In 1910, after graduating from the University, he went abroad to improve his knowledge of anthropology and archaeology. He worked in laboratories and museums of Paris.

In the following years S. I. Rudenko, who lectured, as a privat-docent, at the physical-mathematical faculty of Petrograd University, was engaged in ethnographic studies in the Ufa province. He was the discoverer of the Sarmatian culture in the South Ural region: in 1916, at the request of M. I. Rostovtzeff, a nonregular member of the Imperial Archaeological Commission and corresponding member of the Imperial Russian Academy of Sciences, he dug out four burial mounds near the village of Prokhorovka in Orenburg province — outstanding monuments of the Sarmatian culture. These results were included in the last volume of the series Materials on the Archaeology of Russia published by the Imperial Archaeological Commission.

After S. I. Rudenko defended his master’s thesis, he was elected professor of Tomsk University and then professor of Petrograd University. He occupied different posts in the Academy of Sciences, the Geographic Society, and the Ethnographic Department of the Russian Museum. He was engaged in archaeological, anthropological, and ethnographic investigations in vast areas of Volga region, Kazakhstan, and Northwest and South Siberia. The famous Pazyryk mounds in Gorny Altai whose excavations were started in 1929 are among his outstanding finds.

In the epoch of the “Great Turn” after the October Revolution, the Communist party and Soviet authorities tried to put science on the Marxist foundation. Therefore, old “bourgeois” specialists were persecuted everywhere. From 1928, Dr. Rudenko had been severely hounded by Marxist scholars, who accused him of anti-Soviet views. His name became notorious as a symbol of bourgeois science: in the Academy of Sciences, museums and institutions of higher education a struggle with “Rudenko views” in archaeology and ethnography was.

On August 5, 1930, Dr. Rudenko was arrested as a result of the so-called “case of historians”, or “the academy case”. He spent 12 years in prison, prison camps, and barracks of Belomorkanal and other remote places. These events radically changed the scholar’s life. He had to engage in hydrologic problems associated with the hydro construction. After he had been released and returned to Leningrad, he began to work at the State Hydrological Institute. Only in 1942 could he resume his favorite archaeological investigations by starting work at the Institute of the History of Material Culture of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

In the after-war years, the archaeologist performed large investigations in Kamchatka and Gorny Altai. The State Hermitage exposition has materials of his excavations. They characterize the bright and original culture of Altai nomads of the Scythian epoch. These include unique finds, such as leather and felt goods, among them clothes, world’s oldest carpets and fabrics, weaponry and harness articles, wooden chariots, jewelry, and other pieces of art.

In the after-war years, the archaeologist performed large investigations in Kamchatka and Gorny Altai. The State Hermitage exposition has materials of his excavations. They characterize the bright and original culture of Altai nomads of the Scythian epoch. These include unique finds, such as leather and felt goods, among them clothes, world’s oldest carpets and fabrics, weaponry and harness articles, wooden chariots, jewelry, and other pieces of art.

These discoveries, comparable with those in the period from the 18th century to the beginning of the 20th century, made Dr. Rudenko’s name world-famous. Owing to his fundamental and versatile education and his field investigations, he became a pioneer in applying methods of natural sciences in archaeology. Since the 1950s, Dr. Rudenko became head of the Laboratory of Archaeological Technology in the Leningrad Department of the Institute of Archaeology of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

S. I. Rudenko’s Personal Foundation holds a unique position in the St. Petersburg Branch of RAS Archive, since it has a lot of unpublished materials. It has several unpublished monographs. They include The Paleolithic Art of the North-East Asian Peoples (1963—1964); The Ugrians and Nenets of Low Ob Region (Historical-Ethnographic Studies) (not later than 1960); and Dinlins and Minusinsk Bronze Art of Their Time (1967). The monograph mentioned last is devoted to art bronzes of the Karasuk and Tagar cultures of the Minusinsk basin.

Now the readers have a unique opportunity to get acquainted with one unpublished work of the outstanding scientist: the popular scientific book Dead City of the Ancient Tangut Empire (1968).

Trip to the Dead City

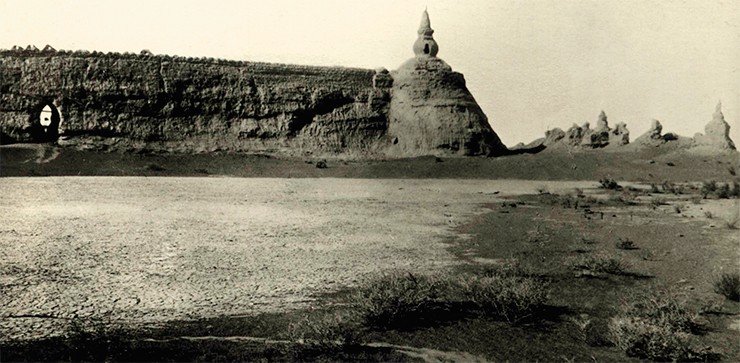

In accordance with the text of the manuscript, the city of Yijinai (Ejina) or Khara-Khoto (Black City in the Mongolian language) was one of the main cities of the ancient Tangut Empire of the Xixia dynasty (1032—1227). It occupied the territory of north-western China with Tibet as its part.

The city remains preserved up to now on the bank of the dry Ejina riverbed (Ejin-gol) in arid and quick sands of the Gobi desert. Formerly the city was located amidst a blooming oasis irrigated from river canals. In 1225 the city was occupied by Genghis-Khan troops. Two years later the history of the Xia State ended. Russian geographer and ethnographer G.N. Potanin wrote in his work Tangut-Tibet outskirts of China and Central Mongolia (1884—1886), “Here one can see a small kerim (walls of a small city), many traces of sand-covered houses, where one can find silver things.”

This information impressed another Russian traveler, P. K. Kozlov, who visited this area as head of the Mongolia Sze-Chuan Expedition of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society (1907—1909) to perform archaeological and ethnographic investigations.

P. K. Kozlov was told the local legend about Khara-Khoto’s death. It goes that the last owner of Khara-Khoto hero Khara-Jia-Jun, who was head of the invincible army, decided to seize the Chinese throne. However, during the war the emperor’s army surrounded the city and decided to deprive the besieged of water. The Ejin-Gol river was turned to the west, and the former riverbed was dammed up with sand-filled sacks. The besieged people started digging a well in the north-western corner of the fortress and dug more than 200 m, but found no water.

P. K. Kozlov was told the local legend about Khara-Khoto’s death. It goes that the last owner of Khara-Khoto hero Khara-Jia-Jun, who was head of the invincible army, decided to seize the Chinese throne. However, during the war the emperor’s army surrounded the city and decided to deprive the besieged of water. The Ejin-Gol river was turned to the west, and the former riverbed was dammed up with sand-filled sacks. The besieged people started digging a well in the north-western corner of the fortress and dug more than 200 m, but found no water.

Khara-Jia-Jun resolved to give his enemy a decisive battle. However, he hid all his wealth in the dug-out well in case he was defeated. The legend runs that no less than 80 carts and wagons, each holding 20–30 puds (1 pud is 16 kilograms) of pure silver, and other valuables, went into the well. The sovereign killed his two wives, his daughter and son, so that the enemy would not abuse them. He was killed, together with his invincible army, in a decisive battle.

The emperor’s troops conquered the city and destroyed it, but did not find the treasures. The treasures were said to remain there, although the Chinese from neighboring cities and local Mongolians tried many times to find them. They explained their failures by the incantation imposed by Khara-Jia-Jun himself. Once, instead of the treasures, fortune hunters dug out two large snakes with glittering red and green scales.

Finds of the Russian Expedition

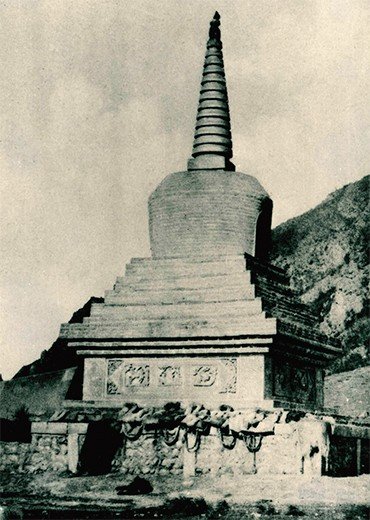

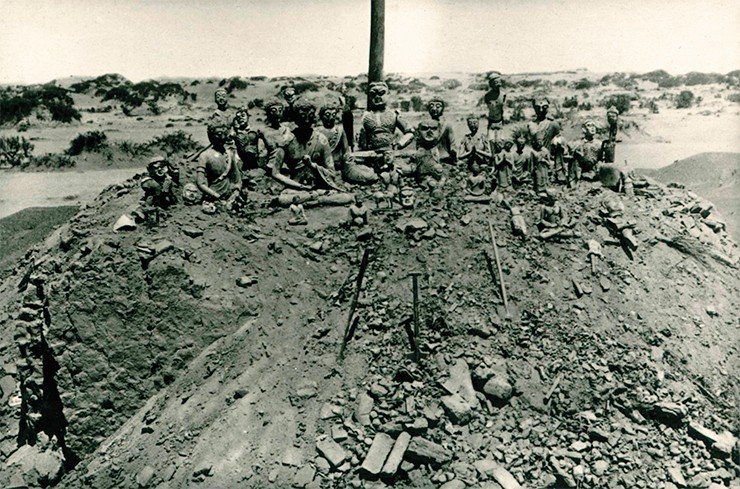

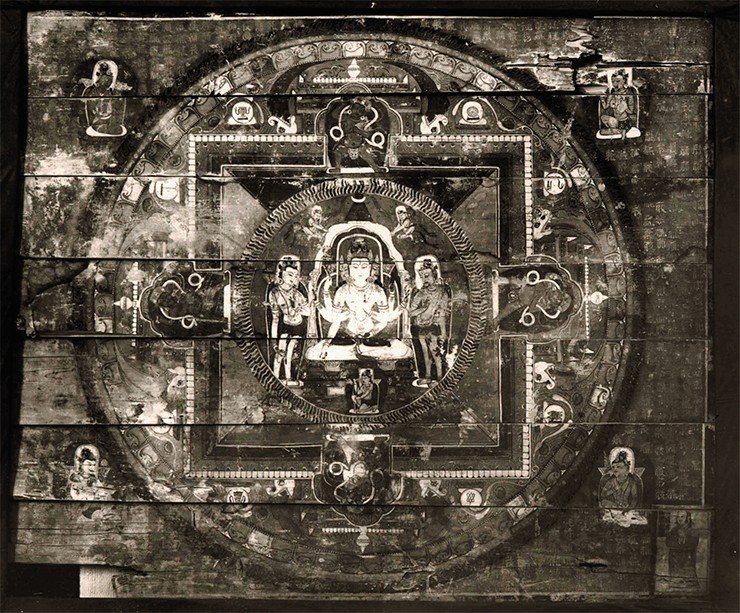

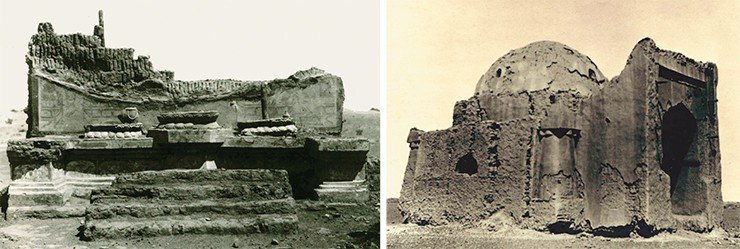

When Kozlov’s expedition entered the Dead City, it started to explore the terrain and look for places for excavations. The most famous artefacts were found in a religious pise building (suburgan) located at a distance of 300 meters from the fortress. Suburgans are successors of the well-known Indian stupas, monuments of important religious events. Subsequently they were erected to serve as sepulchres for lamas (buddhistic monks), who were known for their holiness and feats for the sake of faith.

One dug-out suburgan was named Znamenityi (Russian for “famous”) and had a height of 8—9 m. It had a pedestal, a benching middle, and a conical top destroyed by the time; in the center of the pedestal there was a pole. Twelve clay statues of man’s height stood around the pole facing the center. Large books of Xixia script lay in front of them as though they were lamas holding a religious service. A 50-year-old woman (her skeleton was in a sitting position) was lying in the suburgan. All the treasures — books, icons, statues, and other objects — were scattered in a mess.

![Suburgan Znamenityi [famous] at the beginning of excavations. Photo bottom: clay and wooden statues found in it Suburgan Znamenityi [famous] at the beginning of excavations. Photo bottom: clay and wooden statues found in it](/files/medialibrary/4c3/4c35305ad9a4ee3c3c5d3df3769d17ff.jpg)

In Khara-Khoto, Kozlov’s expedition discovered a very rich collection. It had two thousand books and manuscripts in the Tangut, Chinese, Tibet, and Uigur languages, paintings on varnished cotton fabrics, hundreds of metallic and wooden sculptures, models of suburgans, not less than 300 buddhistic icons of the 12th—13th centuries, including weaving art specimens in the form of gobelins rolled on wooden rolls, and other relics from buddhistic temples. The found Tibet scripts differed greatly from Chinese scripts. This proved that Indian painting had a great influence on the ancient Tibet art and thereby on the Tangut art.

In spite of the legends, Ejina turned out to be inhabited after the Mongols destroyed the Tangut Empire. The documents found in refuse heaps inside the city date back to the period of the Chinese dynasty Yuan (1290—1366). The age of Chinese coins found in the city is the third quarter of the 13th century. This is confirmed by the fact that daties on the Chinese ceramics belong to the time of the Sun and Yuan dynasties and, possibly, to the beginning of the Ming dynasty (1369—1694).

Although Kozlov’s expedition did not find the treasures of the hero Khara-Jia-Jun, the excavations discovered cultural-historic monuments of world significance whose value is much greater than that of the legendary treasures. The finds allowed scientists to reconstruct the story of the forgotten Tangut state Xixia, which existed for about 250 years on the territory of present-day northern China.

Tangut inhabitants

S. I. Rudenko gave comprehensive ethnographic characteristics of the population of the ancient Tangut Empire. It is based on all available sources: information of Chinese chronicles and Venetian Marco Polo, a famous traveler of the 13th century, data about the life of the Tanguts related by Russian travelers who visited Tangut in the 19th century, and the materials of Kozlov’s expedition.

Tangut inhabitants are the Tanguts and north-eastern Tibetans whose language belongs to the Tibetan-Burmese group. The Tanguts were ancestors of the Tibetans. They came to Tibet, the Kuku-Nor lake, in the 4th century B. C. Physically, the Tanguts, like Tibetans, differ considerably from the Mongols and, in the opinion of Rudenko, they are more like Gipsies. Their religion was mostly Buddhism. “Among them were Turkomen (Uigurs) and an insignificant number of Christians and Moslems.”

The Tanguts were hunters and cattle-breeders. They bred camels, yaks, and other cattle. However, they did not have many horses. Besides gardening, they were engaged in farming: they sowed barley, wheat, and peas. They used a primitive plow for their fields, and broke ground clods with the help of mallets.

The black marquee covered with coarse material made from yak’s wool was the most widely used home for the Tanguts and the only kind of home for nomads. Camel and yak wool weaving flourished. In forest areas the Tanguts lived in loghouses (izbas), and woodless areas - in houses made of stone or bricks, similarly to Chinese houses. They were surrounded by high walls (4-6 m high).

As an ethnographer, S. I. Rudenko gives a detailed analysis of religions (Buddhism, shamanism); and characterizes family relations, customs and ceremonies. He paid special attention to polyandry and polygamy of the Tanguts. As an archaeologist, he noted the differences in the funeral ceremonies in different regions of the empire. For instance, in north-eastern forests the dead were burned; the southern Tanguts, on the contrary, left dead bodies to be eaten by birds and animals; only especially esteemed people were burned in the squirmed position (dead bodies were tied with straps, with the legs pulled up to the head).

RUSSIA’S FIRST SCIENTIFIC ARCHIVE

There is a modest two-storied outbuilding at the Universitetskaya Embankment in St. Petersburg, in the yard of Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkammer) and the Zoological Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences. People do not know what treasures are concealed in that homely building. The oldest scientific organization of our country — the Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences (now it is the St. Petersburg Branch) — is located there. It was created on the decree of Emperor Peter Alexeyevich (Peter II, grandson of Peter the Great) in January 1728.

Modern archaeologists refer to archival documents on the history of specific regions and architectural monuments only occasionally. As a rule, they use materials not older than 100—150 years. Such documents are mainly concentrated in the Scientific Archive of the Institute of the History of Material Culture of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, which has files beginning with 1795. Scientific documentation of the second half of the 20th century is kept in the Archive of the Moscow Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

The Archive of the Academy of Sciences has thousands of documents on the archaeology of regions of the Russian Empire and of the USSR, from 18th to 20th century. They include scientific works and materials of well-known scientists, pictures and cartographic documents, plans and drafts, photographs, negatives, diapositives, etc.

Materials of the Academic Archive are the most valuable source of information on the history of science beginning with the times of Peter the Great. Among them are mostly unpublished materials of the Siberian expedition of D. G. Messerschmitt, documents of academic groups of the First and Second Kamchatka expeditions of V. Bering, and the Trapezund military-archaeological expedition... The materials of complex polar expeditions headed by E. V. Toll, G. Ya. Sedov, G. L. Brusilov, V. A. Rusanov, and of many other expeditions have also come down to us.

Among the materials kept in these buildings, of special importance are the stocks of the Kunstkammer (the Museum-Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography), the Society of Siberian Studies at the Museum, the Russian Archaeological Institute in Constantinople, etc. Personal papers of outstanding scientists of the 18th—20th centuries are also kept in the St. Petersburg Archive. These are personal papers of the first Academician-historian G. Z. Bayer, first Director of the Archive Academician G. F. Muller (Miller), encyclopaedist M. V. Lomonosov, anthropologist K. E. von Baer, historian and archeologist A. S. Lappo-Danilevskii, traveler P. P. Semenov Tian-Shanskii, geologist S. V. Obruchev, archeologist A. P. Okladnikov, and others. This list of famous Russian scientists can be continued.

Researchers of the St. Petersburg Archive have at their disposal extremely valuable retrospective information. Colleagues-archeologists are invited to visit the Archive. Joint scientific, publishing, and exhibiting projects are always welcome.

E-mail address of the Archive is archive@spbrc.nw.ru

The manuscript of S. I. Rudenko’s monograph “Dead City of the Ancient Tangut Empire” includes three variants of the text and draft notes. It is our good luck that we have not only the manuscript itself, but also a full set of book illustrations such as photographs, pictures, and maps. This gives us hope that the work unpublished during the scientist’s life will be issued in the nearest future.