Petr Bryukhanov of the Tobolsk Guild of Craftsmen

The development of silver handicraft in Tobolsk

After the Voguls and Ostyaks had entered the Russian Empire, they were actively involved in trade relations with Russian people. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Tobolsk was a center for manufacturing silver dishes for the needs of non-Russian peoples. The small figurines purchased by Voguls and Ostyaks served as tributes to their guardian spirits. Silver saucers were often used to denote faces on deities’ figures. Fixing a silver or copper saucer to a guardian spirit’s figurine made of fur coats, robes, or shirts emphasized its sacred image. In general, we may talk about a specific cultural phenomenon, i.e., the specialized production of Russian metal articles for religious needs of the Khanty and Mansi. The rightful place in this process belongs to the Tobolsk craftsman Petr T. Bryukhanov

Ermak’s expedition marked the beginning of the construction of the first Russian towns beyond the Urals. In 1586, the Tyumen fortress was built; a year later, Tobolsk was founded at the confluence of the Tobol and Irtysh rivers. It became the center of the administrative and religious authorities in Siberia for many years.

The population of Tobolsk was actively engaged in agriculture, trade, and various crafts. In 1624, there were 42 craftsmen specializing in 18 crafts; a hundred years later, their number increased to 665 craftsmen specializing in 42 crafts.

The map of Tobolsk, which was drawn by S.U. Remesov at the end of the 17th century, shows silver trade arcades at the foot of Troitsky Cape, where the Kremlin stands. The main customers of silversmiths were Tobolsk bishops, who sent silver crosses and chalices—indispensable objects of public worship—to Siberian churches and monasteries. Generals and governors were among their customers too.

It is well known that after 1711, Swedish captives were exiled to Tobolsk. Some of the officers were engaged in silver production; one of them had studied this craft when he was young. In Tobolsk, he organized a large workshop sponsored by Governor Gagarin. The workshop produced silver sets and other valuable objects. Later some of these officers founded their own workshops.

The development of silver craft in Tobolsk

In the first half of the 18th century, people began to mine silver and copper in Siberia: in 1726, the first silver was smelted at Akinfy Demidov’s Kolyvan-Voskresensky mine.

In 1721–1724, according to Peter the Great’s reform, the urban population was divided into “regular citizens,” who possessed property, and people without property, or “mean people.” The “regular citizens” were to unite into guilds and workshops, with this rule being obligatory for craftsmen who lived in towns.

In 1723, a provincial magistrate opened in Tobolsk; it registered all the craftsmen. In 1757, the office of an assay-master for Tobolsk was approved.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, in all Russian towns, it was the responsibility of an assay-master to put the following marks: a hallmark with the coat of arms of the town or region in a shield of a particular shape; a hallmark in a square shield of the assay-master himself, with the initial letters of his name and surname, with the year or without it; a mark of two digits denoting the standard of silver. Craftsmen, workshops, and factories were obliged to put their hallmarks before presenting the products to the state assay-master. Hallmarks with two or three initial letters of the craftsman’s name and surname were placed in shields of different shapes with various typefaces.

In 1765, there were 13 silversmiths in Tobolsk. Local craftsmen purchased silver from China and Bukhara at the Irbit fair; in the late 1770s, merchants brought 50–100 poods* of silver from Bukhara to the Tobolsk province every year. Silver and niello products manufactured in Tobolsk in the 1770s were decorated with local scenes: a skiing hunter, an equestrian chasing a deer, etc. The collection of the State History Museum has a silver milk jug dated 1778, which is decorated with an image of a man with a dog who are hunting a fur-bearing animal. In the 18th century, a set of three silver glasses cost 15 rubles and 87 kopecks.

Some of the silver items manufactured in Tobolsk in the 1770s had personal hallmarks composed of Latin letters. They belonged to Polish confederate craftsmen who had been exiled to Tobolsk. However, the majority of the craftsmen were Russians.

In his report of July 6, 1891, Priest I. Goloshubin described a ritual devoted to successful bear hunting: “They put the stripped fell on the table in the front part of the room, straighten its paws and head, then put on each of its claws as many rings as it can fit, and fix a silver plate to its nose…” [From the History of the Obdorsk Mission, 2004, p. 181]We know the names of the Tobolsk craftsmen who worked in 1780–1790. The archive of the Tobolsk Crafts Administration of 1788 had a list of silversmiths that included 11 lower middle-class men and 12 men from the guilds. Petr Bryukhanov, 30 years old, was among the latter.

In 1806, the number of silversmiths reduced to 19; in 1809, there were 7 lower middle-class artisans, 5 craftsmen from the guild, and 2 apprentices. In 1819, only “Petr Bryukhanov of the Guild, the disabled retired Yakov Shvyrev and the coachman Yakov Sterkhov” had silver forging furnaces.

Unfortunately, very few articles made in the Tobolsk workshops have been preserved to this day. A few silver articles (oval and rectangular saucers and plates) were discovered by the Polar Ethnography Group, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography SB RAS in 1983–2013 in the home sanctuaries of the Khanty and Mansi. Most of the newly found articles have Petr Bryukhanov’s hallmark on the face side. Before this discovery, the next-to-skin icon “Our Lady of the Sign” was widely known (with the hallmarks on the back: the emblem of the Tobolsk province, 1794, and Bryukhanov’s personal hallmark: ПБ (cyr.)). The icon is stored in the Tobolsk State History and Architecture Museum Reserve. We have found that there are unattributed items with the hallmark ПБ (cyr.) in some other museums as well.

Products of Petr Bryukhanov’s workshop in Tobolsk

At present, there exist 18 pieces of silver articles (beside the icon) manufactured at Petr Bryukhanov’s workshop: eleven saucers, one small square plate, three rectangular and one oval plates, and two anthropomorphic figurines. Three items are kept at the Shemanovsky Yamalo–Nenetsk Museum Exhibition Complex in Salekhard; two, at the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography in St. Petersburg; two, at the Tobolsk State History and Architecture Museum–Reserve; one, at a museum in the village of Sarapul, Berezovsky District of the Khanty–Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra; one, at the Museum of Nature and Man (Khanty-Mansiysk); seven, at the Museum of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography in Novosibirsk; and two, in a private collection in Tobolsk.

The saucers are small plates with a convex bottom; the rectangular plates are flat; the oval ones are slightly curved along the axis. The items were cut out of silver planks; most of the pictures were made by embossment; some items, by engraving.

The earliest product made by Bryukhanov is dated 1793; the latest one available, 1822. A small plate with a curved border (10×10 cm) is dated 1793; it has hallmarks on the face side: the coat of arms of Tobolsk (a pyramid on the podium, with military fittings, flags, drum, and halberds); “…93,” the assay’s mark by M. Bogdanov (the upper part of the letter Б (cyr.) is visible); and Petr Bryukhanov’s hallmark П•Б (cyr.) in a square frame. In a round frame at the center of the plate, there is a deer galloping to the right and a tree behind it.

At present, we know four silver saucers with a deer image at the center (the animal is moving either to the left or to the right) and trees, bushes, and hills in the background. The border of one of the saucers has no images; two items are decorated with branches and leaves; the last specimen has figured rosettes, two fish, and a bird.

The “deer series” concludes with a saucer depicting a hunter chasing a deer.

At the center of three other saucers, we can see an image of a bear hugging a massive tree bough.

Another interesting saucer shows a warrior on horseback; the border is decorated with the figures of four dogs and three birds.

There are three rectangular plates that are also attributed to Bryukhanov’s mark. All the three depict a deer-hunting scene. There are differences in the number of figures: the first plate shows a hunter, a dog, a deer, and a bird; the second shows one hunter chasing a deer, while the other one is setting a dog on a squirrel; and the third plate shows two hunters, two deer, a squirrel, and a bird. The lowest edge of the plates has holes to which small figurines of fish and birds were once attached; now most of them are missing.

The only oval plate made by Bryukhanov is decorated with a deer against the background of trees and bushes.

Two saucers with pictures from J.G. Georgi’s book

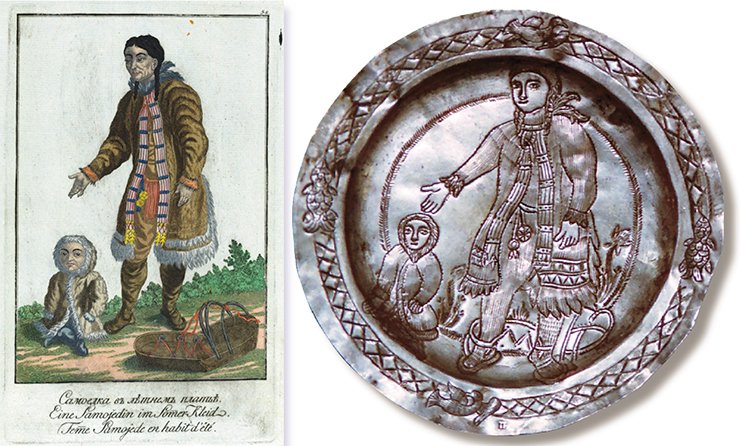

Special mention should be made of the two saucers stored at the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography, St. Petersburg. The face side of the first saucer shows an image of a standing woman and a child sitting beside. The bottom of the second saucer is decorated with a figure of a man with a bow in his hand. N.F. Prytkova found that the images on these saucers (she calls them small plates) were copied from illustrations in J.G. Georgi’s book A Description of All the Peoples Inhabiting the Russian State (1776).

She also noted that the first plate had a hallmark of the letter П (cyr.) and the second, the hallmark of IПБ. According to N.F. Prytkova, both plates were manufactured in St. Petersburg as evidenced by the marks and the images copying the illustrations in Georgi’s book. There are two wrong statements here. First, in the first half of the 19th century, the hallmark was indicated by figures 84 in a rectangular shield. Second, the letters П (cyr.) and IПБ (cyr.) have no relation to St. Petersburg because from 1741 to the end of the 19th century, silver things produced in the capital bore a hallmark with the city’s coat of arms (two crossed anchors and a scepter).

The Kunstkamera staff kindly allowed us to see those exhibits of extraordinary interest. It should be mentioned that hallmarks on Siberian articles were often made carelessly or were damaged; sometimes two similar marks were overlapping.

On the first saucer from the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography, we can see only the letter П; the right letter is missing, and it might have been the letter Б. The hallmark on the second saucer is not IПБ, but IП•Б. The upper line of the frame is uneven; there is a break between I and П. Therefore, it could be assumed that we see two overlapping marks, instead of the hallmark IП•Б. The first application of the П•Б hallmark was unsuccessful, and then it was applied once again. As a result, we can see the vertical line of the letter П of the first mark, and the lower part of this letter a little to the right.

Another argument for the Tobolsk origin of the two saucers from Kunstkamera is a silver saucer with an image of a deer from the settlement of Hulimsunt: it also has the П•Б hallmark. The images of fish and birds decorating the borders of the plates from the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography, and those from Hulimsunt were made in the same manner.

Therefore, my version is that the two silver saucers with Georgi’s scenes from the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography were manufactured not in St. Petersburg, but in Tobolsk by craftsman Petr Bryukhanov, whose Russian initials are П.Б. (cyr.). Both silver saucers have high assay value; the silver mark is 916. The items might have been made from the customer’s silver.

On November 30, 1869, the Berezovo solicitor reported to the Governor of Tobolsk: “In August this year the settler Petersen stole from the shaitan that belonged to the local tribe of 200 people. The shaitan was located 15 miles from Toupogol yurts, in an empty space in the mountains… He had 125 rubles in silver coins. The shaitan’s property was five small golden plates the size of a tea saucer and smaller, one golden cup, a large number of small silver plates …; 50 silver forehead decorations three fingers wide, more than four vershoks (18 cm) long, and thin…” [And Here Comes the Dawn of Christianity…, 2003, p. 231--233]The saucers from the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography might date back to the 1820s. Georgi’s book was published in 1776, so there was enough time for it to reach the province. Culturally, Tobolsk was a fast developing town: in 1790, e.g., the city published two parts of The Historical Magazine Selected from Various Books (excerpts from Description of All the Peoples… might have been easily included there). In 1793, there appeared a publication named The Scientific, Economic, Moralizing, Historical and Entertaining Library for the Benefit and Pleasure of Various Readers of All Ranks. It looks as if the craftsman or the customer had only the third volume of Georgi’s book, which contained pictures of the Far Eastern peoples, not of Ostyaks.

Although the articles made at Bryukhanov’s workshop (silver saucers and square and oval plates) were of different shapes, all of them had the same plot, i.e., hunting scenes. The only exception is two figurines, both depicting a man standing in the same position: one hand up, the other down. The meaning of this posture might be associated with dancing.

Russian articles in the rituals of the Khanty and Mansi

The silver saucers were mostly used to denote the deities’ faces. Sometimes the saucers offered to deities as gifts became the cores of their figures in home sanctuaries. Fixing a silver or a copper saucer to the figure of a guardian spirit, which was made of fur coats, robes or shirts, emphasized its sacred nature. In the settlement of Anzhigort, the Khanty family of the Eleskins used a silver plate depicting a bear as the core of the guardian spirit’s head, which was made by folding shawls.

Quite often silver saucers accompany sacrificial blankets in the home sanctuaries of Khanty and Mansi. As is known, the sacrificial blankets were made as gifts to Mir-Susne-Hum, and were decorated with its figures. After making the blanket, they held a special ceremony of sacrificing a horse to the Heavenly Rider. The Khanty believed that during the ceremony the deity would come on his winged horse from the heaven to the earth. The members of the ceremony put four silver saucers on the grass or on the snow, so that the deity’s horse would not touch the sinful earth with its hoofs.

There are several examples of how the northern Mansi kept silver saucers together with sacrificial blankets in their homes. These are P.E. Sheshkin in the village of Lombovozh, N. Puksikov in the village of Hulimsunt, and K. Pakin in the village of Verkhneye Nildino. The rectangular plates were used in the Khanty and Mansi’s rituals to decorate the figures of their guardian spirits, or as sacrificial gifts for magical purposes and as a head adornment for the members of the bear feast.

In 1962, the Khanty-Mansiysk History Museum acquired a figure of the female guardian spirit of the Kazym Khanty Vut-imi; it had been kept in a holy barn near the Kels-Yugan River, not far from the settlement of Yuilsk (now the Beloyarskii District). The deity’s figure consists of a wooden frame covered with kerchiefs and decorated with metal ornaments that include five silver plates of the 15–17th centuries and six Russian silver and copper plates made in Tobolsk or in craft centers in the north of West Siberia in the late 18th and early 19th century.

Another group of plates could be classified as gifts to a deity; the offering was accompanied by an appeal for successful hunting (it was depicted on the plate). They called these plates yeer, which means “tribute.”

The last group of plates is classified as elements of the headdress worn by men who took part in dramatic scenes and dances associated with heroic ancestors during the bear feast.

Five plates made of silver, silver-plated brass, and tin were stored in Lombovozh in the so-called community house, among other sacred objects that belonged to the Sheshkin Princelings of Liapin. According to V. N. Chernetsov, regular ceremonies with warrior dances were held in Lombovozh. The men who appeared as mythical heroic ancestors had swords in their hands, wore silk robes, and had cotton bands with fixed plates on their heads. The man with a metal plate on his head “transformed” into the deity whose image he wore.

There are very few oval plates discovered in the villages of Khanty and Mansi. They have the same shape as the wrist protecting elements used for bow shooting. Judging by the images on these plates, they might have been offered to the deities with an appeal to protect their deer herds or to favor successful hunting.

The both male figurines played the role of family guardian spirits: one for the Mansi in the village of Yasunt; the other for the Khanty in the village of Zeleny Yar. They were dressed in robes and had small headdresses made of cotton cloth.

After the Voguls and Ostyaks had entered the Russian Empire, they became actively involved in trade relations with Russian people, who could meet the demand of local Siberians for metal articles: dishes, bowls, figurines, saucers, plaques, etc. Russian craftsmen and traders continued the tradition of supplying silver and copper utensils to the north of Siberia. They must have made their articles after the earlier specimen from Iran, Central Asia, Volga Bulgaria, and the Kama region.

The non-Christians of the Berezovo okruga (‘district’) (1783) “have idols made of wooden stumps of different sizes, with faces cut on thin iron…” [Andreev, 1947, p. 96]Large cast silver Iranian and Bulgar dishes were replaced by stamped plates, silver and copper saucers depicting riders, animals, and hunting scenes. Bulgar head adornments might have inspired Russian craftsmen to produce rectangular plates depicting hunting scenes. The ritual practice of the 19th and 20th centuries used Russian votive copper shields (to protect the wrist) that were similar to the earlier Bulgar and Kama items. Thus, the tradition was maintained mainly due to the demand from the Voguls and Ostyaks.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, in Tobolsk there was a center for producing silver dishes for the needs of non-Russians. There were also workshops in Obdorsk and Berezovo. Unlike in the previous centuries, the workshops were set up in Siberia, close to their customers.

Russian silver articles became a part of family worship symbols: small figurines bought by the Voguls and Ostyaks were sacrificed to guardian spirits or were used as a core of their figures. In general, we can speak about a specific cultural phenomenon, i. e., specialized production of Russian metal articles for the religious needs of the Khanty and Mansi during the 18th and 19th centuries. The rightful place in this process belongs to the Tobolsk craftsman Petr T. Bryukhanov.

*Translator’s note. The pood is a unit of mass equal to approximately 16.38 kg (or 36.11 pounds)

References

Baulo A. V. A bogatyr and his bride (a silver plate from the Synya river). Archaeology, Ethnography and Anthropology of Eurasia. 2001. N 2(6). Pp. 123–127.

Gondatti N.L. Sledy yazychskikh verovanii u inorodtsev Severo-Zapadnoi Sibiri (Traces of Pagan Beliefs in Non-Russian Peoples of North-West Siberia). Moscow: Tip. Potapova, 1888 [in Russian].

Elfimov A.G. Tobol’skoe serebro s XVIII v. do nashikh dnei (Tobolsk Silver from the 18th Century to This Day). Tobolsk: Vozrozhdenie, 2010 [in Russian].

Postnikova-Loseva M.M., Platonova N.G., and Ulyanova B.L. Zolotoe i serebryanoe delo XV—XX vv. (Gold and Silver Craft in the 15—20th Centiries). Moscow, 1983 [in Russian].

Prytkova N.F. Metallicheskaya kul’tovaya posuda u Ugrov (Cult metal tableware of the Ugrians). Sb. Muz. Antropol. Etnogr. 1949. Vol. 10. Pp. 39—46 [in Russian].

Sukhorukova N.V. Tobol’skoe serebro XVIII v. (Tobolsk silver in the 18th century). Proc. Conf. Art Museum: Collections and Regional Culture. Tyumen. 1993. Pp. 22—26 [in Russian].