Traces of Chinese Chariot

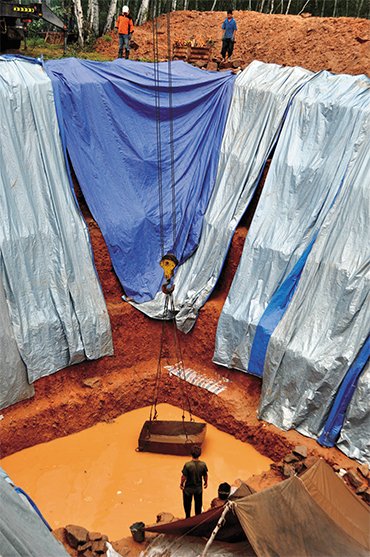

In summer 2012 the Russian-Mongolian archaeological expedition organised by the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography SB RAS (Novosibirsk) and the Institute of Archaeology (Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Ulaanbaatar) continued to study the Xiongnu burial site at Noin-Ula in Nothern Mongolia first explored by the expedition of the Russian traveler P.K. Kozlov in the beginning of the last century. Three months after the excavation in Noin-Ula mound 22 began, a Chinese chariot was discovered at the entrance of a huge burial pit at the depth of almost 10 m below the ground

Three months after the excavation in Noin-Ula mound 22 began, a Chinese chariot was discovered at the entrance of a huge burial pit at the depth of almost 10 m below the ground

The chariot was rolled down a steep dromos after the deep pit where the remnants of a noble Xiongnu repose was tightly filled with the ground.

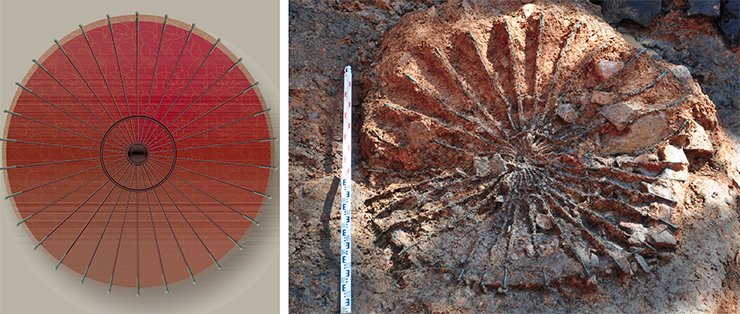

Everything in this fine article of the Chinese masters testified to a high status of the deceased. A magnificent red silk umbrella doubled with a more intensive purple silk was stretched over 30 wooden ribs covered in black lacquer, with cast iron spikes. The hooks of the spikes to which the umbrella material was attached were wrapped in strips of purple silk. A light basket was covered in black lacquer on the inside and the red one on the outside. The lacquered sides were supplemented by wooden “flying grids” over which Venetian red silk was stretched.

The cart tightly filled with stones had been taken off its wheels and placed at the south side of the entrance to the burial pit. Two large wheels had been put flat down at the front on both sides of the basket; the umbrella had been taken off the pikestaff and put outside half covered with stones. Only after that it was buried in the ground for centuries.

Two thousand years have not passed without losses for this magnificent ancient creation: wood and silk fell to ashes while the metal parts became rusty. The chariot disappeared as a thing, but its traces have been preserved in clay similarly to the footprints of fossilized animals. Today it continues to exist in detailed drawings and photos.

Looters came first

The chariot discovered in Noin-Ula mound 22 belongs to the “yao che” type of chariots widely spread in the Han times. It is a type of light two-wheeled carriage with an umbrella harnessed to one or two horses. Such carriage which could be used as a military or pleasure vehicle could carry 2 people.

Along with the other dainty things, such chariots were among the gifts the Han court gave to the Xiongnu rulers chányú. The purpose of making such presents was to weaken the people of Xiongnu and make them dependent on the Han Empire by introducing them to the temptations of a higher material culture. Such policy resulted in a considerable number of Chinese chariots crossing the steppe back and forth. Their images can be seen carved in the rock in the mountains in Mongolia (Novgorodova, p. 192—206), while their fragile remnants have been preserved in many elite burials excavated before (in Kondratievsk mound 7; in Noin-Ula mounds 25 and 6; in the mound 7 in Tzaram burial ground; in the mound 1 at Gol-Mod burial ground, etc.).

Who was then buried in the burial pit at the depth of more than 16 m with such a significant gift? It is always a rhetorical question when we talk about the Xiongnu elite because their burial grounds are distinguished by being completely looted. It can be concluded that the buried themselves were main aim of looting because not a single Xiongnu mound that has been discovered so far contains the bodies buried in them.

How can such an unusual fact be explained? Without doubt, the buried were accompanied by some things, such as armour and jewellery of value for the looters. However, the bodies themselves were of a particular interest to them too. It is well-known that dismembering the enemy’s body parts was commonly practised in the ancient times as well as in the Middle Ages. Its purpose was to destroy completely the connection between the living descendants and their deceased predecessors whose help and protection they could no longer count on after the destruction of a carefully preserved body.

It is interesting to note that not only the Barbarians treated the bodies of the deceased this way, but also the Xiongnu. It is known that in 15 AD the Chinese Emperor Wang Mang ordered his ambassadors to dig out the body of Zhizhi Chanyu and flog it. It is not known whether it was done or not, but the fact that it was possible remains.

That is why it is not surprising that there are no skeletons of the deceased in the burials of noble Xiongnu, with only separate bones or teeth occasionally found in the burials. As a result it is almost impossible to identify who belonged to the Xiongnu elite using the results of anthropological research only. For this reason it is so important to research even the scarce anthropological material Noin Ula mounds give access to using paleogenetic methods. This information could help to clarify quite a lot in the history and culture of this legendary ancient people.

Under the sign of Unicorn

Noin Ula mound 22 has not escaped the fate of all Xiongnu burials as it was looted in due time as well. The looters left the tool with the help of which they forced open the vault and the coffin at the bottom of the burial chamber. It was a wooden sledge hammer, simply a piece of trunk with a bough, a primitive tool which allows us to judge how well the looters – in essence nomads similar to the Xiongnu themselves – were technically equipped.

In the inner burial chamber of the mound the coffin rested on two wooden support posts, with the coffin cover lying next to it. Initially the coffin was decorated with a rhomb ornament from criss-crossed wooden planks and four-petal rosettes whose form repeated that of the persimmon receptacle resembling a leaf “skirt” at the base of the fruit. In ancient China this fruit symbolized happiness and joy of life. The rosettes were covered with a layer of thick golden foil, which the looters torn away.

The coffin was practically empty inside, with only some decayed tissue and a layer of decomposed millet grains left at its bottom. In China covering the coffin’s bottom with millet was a tradition connected with the idea of rebirth. There were also a number of original small golden clothes decorations in the coffin.

The bottom of the burial chamber was covered with a thick felt carpet covered with a cloth with a spiral ornament. Fragments of textile articles left by the looters were displayed besides the coffin.

In the north-eastern corner of the corridor between the outer and inner burial chambers, several human bones were discovered lying over the silver plate of the horse’s harness. They were heavily burnt, with the traces of fire also spotted on the horses’ brasses. It seems that the looters had used a torch, later throwing it into the corner as a result of which the bones and jewelry were charred.

In the north-eastern corner of the corridor between the outer and inner burial chambers, several human bones were discovered lying over the silver plate of the horse’s harness. They were heavily burnt, with the traces of fire also spotted on the horses’ brasses. It seems that the looters had used a torch, later throwing it into the corner as a result of which the bones and jewelry were charred.

Horse harness plates are made of silver and decorated with elegant images of the unicorn. In the ancient Chinese bestiary this animal was the third in order of importance among the mythic animal, with the dragon and magic “sun” bird Fenghuang, coming first. It was also the leader of fur animals.

According to the ancient ideas, the unicorn appeared in public only at times of general happiness and wealth. This is probably why its images were present in horse harness decorations manufactured during the rule of Wang Mang (9—25 AD). In the end he was the only state leader of the Early Han who officially announced the start of tai pin, an era of complete world order for the Chinese and Barbarians. He tried to present his rule as the arrival of the “era of great tranquillity”, with the images of unicorns becoming its visual representation.

Similarly to the other Noin Ula mounds, a great amount of thin tightly braided hair was discovered in the corridors formed by the walls of the outer and inner burial chambers. (The total number of braids discovered in Noin Ula mounds has exceeded 150). This discovery remains a mystery and leaves a lot of questions to be answered: who did the braids belong to and how did they end up in the tomb. The most important question though is what for they were placed there.

A number of different hypotheses have been suggested in an attempt to explain this phenomenon. According to one of them, the cut braids could serve either as a sign of mourning and as such substituted human sacrifice in the form of supporters and concubines or gifts to the ruler from subordinated tribes. However, at present none of these hypotheses can be backed by some proof.

Unfortunately, the hair from the Xingnu burial cannot be studied using paleogenetic methods because unlike the hair of the Pazyryk people preserved in permafrost, it has severely degraded. However even so it remains an invaluable source of information which can be obtained by means of its element analysis.

Made in China

The research carried out at three large mounds on the territory of Noin Ula burial ground by the Russian-Mongolian expedition in 2006—2012 as well as the excavations of the burial mound 7 at Tzaram burial ground (Minyaev, 2000–2005) and the burial mound 54 at Ilmovaya pad burial ground (Konovalov, 2008) in Transbaikal helped to single out a number of patterns in the burial ceremony the Xiongnu elite observed. All these burial mounds were dug by hand, thanks to which it was literally possible to see a typical structure of the burial pit.

A typical Xiongnu burial presents a deep five-step pit, to which a corridor known as dromos oriented towards the south leads. It is known that the orientation of the main entrance towards the south as well as deep burial pits with stairs descending to them are typical of a variety of Chinese architectural complexes (Kravtsov, 2004).

A typical Xiongnu burial presents a deep five-step pit, to which a corridor known as dromos oriented towards the south leads. It is known that the orientation of the main entrance towards the south as well as deep burial pits with stairs descending to them are typical of a variety of Chinese architectural complexes (Kravtsov, 2004).

There is a double wooden (pine) burial vault at the bottom of the pit. It presents an airtight, finely adjusted building created by the people who had good skills in working with wood. The same can be said about the coffin itself made and decorated according to the Chinese tradition.

Contemporary Mongolian historian Baabar, the author of the book “The History of Mongolia: from the world dominance to a soviet satellite” (2010), points out that “a nomad is indifferent to the notion of constructing a building he did not and could not do” (p. 379). Thus it is clear that the Hans were directly involved in erecting the burial constructions of the Xiongnu elite.

The things that constitute the balk of the finds, including silver badges, silk material and things made of it, jewelry made of jade as well as the fragments of lacquer items are of the Chinese origin as well. The rest of funeral gifts, for example, wool fabrics, are represented by the items imported from the west. The Chinese archeologists point out that it is very difficult for them to single out the Xiongnu burials among those of the Han the because the difference between them on the Chinese boarder (for example, in Qīnghǎi) has practically worn away.

It should be admitted that the culture of the Han China conquered the Steppe, since the nomads had nothing other than their lifestyle to oppose it. However, when the Middle Kingdom was torn by internal conflicts and wars, the Hsiung-nu, as the Chinese called them, conquered and looted the Jinyang capital Luoyang. Then by the middle of the second decade of 4 A.D. Early Zhao, the Empire of the Hsiung-nu tribal leaders, almost completely occupied the basin of the Huáng Hé river. Similarly to the traces of the Han chariot, the culture of the Ancient China in the Steppe has irretrievably disappeared in time and space.

The field study of Noin Ula mound 22 is complete. What lies ahead is a thorough study of this burial complex, which contains a large number of unique items in need of restoration and conservation. For now the mound is still full of mysteries.

N. V. Polosmak , Doctor of History, and E. S. Bogdanov, Candidate of History

(Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography SB RAS, Novosibirsk), Russian-Mongolian expedition, Noin-Ula, July 2011

References

Novgorodova Je. A. Drevnie izobrazhenija kolesnic v gorah Mongolii // Sovetskaja arheologija. 1978. № 4.

Kravcova M. E. Istorija iskusstva Kitaja. SPb: Lan’, Triada, 2004.

Rudenko S. I. Kul’tura hunnu i noin-ulinskie kurgany. M.-L, 1962. 206 s.

Konovalov P. B. Usypal’nica hunnskogo knjazja v Sudzhi (Il’movaja pad’, Zabajkal’e). Ulan-Udje, 2008.

Polos’mak N. V. i dr. Dvadcatyj noin-ulinskij kurgan. Novosibirsk: Infolio, 2011.

The research has been supported by RGNK grant No.12-21-03554е(m) and Gerda Henkel Stiftung grant