Pineapples under Pine Trees. The Botanical Garden of the Basnins Merchants and How We Can Fight Them

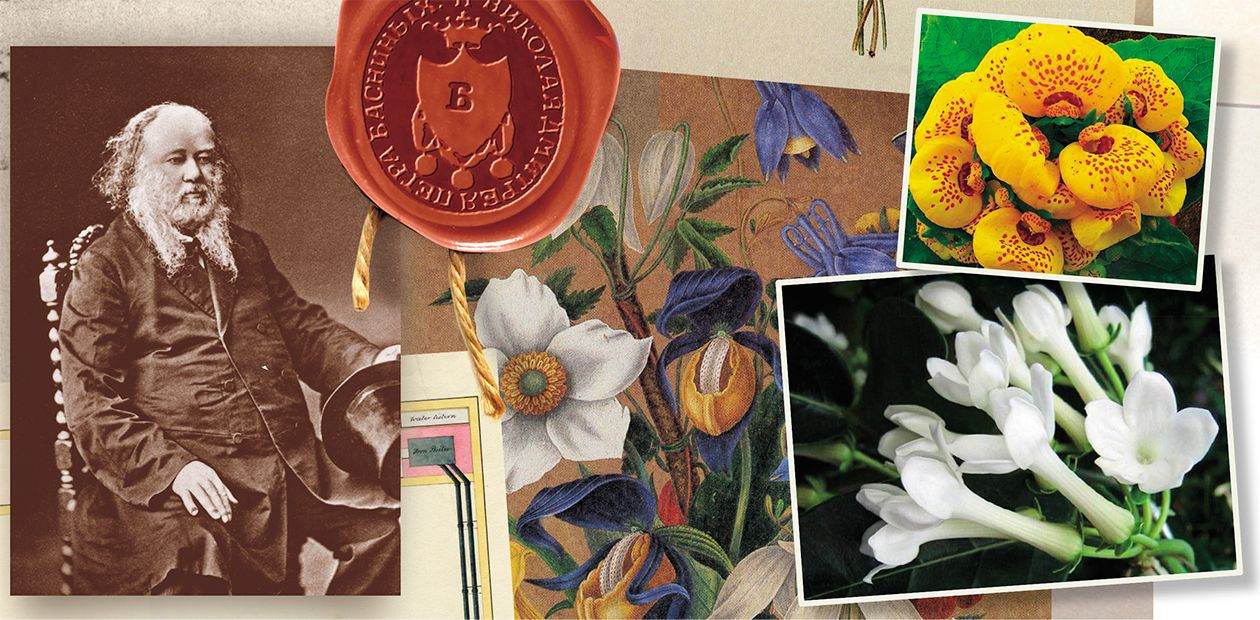

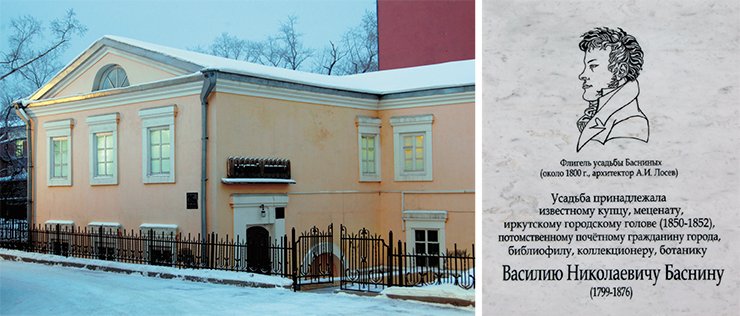

Deeds done by enterprising and creative people, living ahead of their time, tend to be perceived as eccentricities, and only descendants can appreciate their true meaning for the culture and national flourishing. A remarkable example of this kind is Vasily Nikolayevich Basnin – not only a successful Siberian merchant and representative of a well-known merchant family, but also a talented and diverse personality, devoted to the idea of public service. Apart from music, theater, and collecting books and works of art, his interests included botany and gardening – to the extent that he set up, in Irkutsk, the legendary “Basnins’ garden,” famous far beyond the Russian Empire

Тhe tradition of creating gardens – man-made “oases” of life – dates back to the faraway past . Many beliefs closely associate happy life with a beautiful garden-paradise, a place of god.

By the modern classical definition, a botanic garden is a “documented collection of living plants used for public display as well as for educational and scientific purposes” (Jackson, 1999). In fact, botanical gardens are kind of “bridges” connecting plant kingdom and man, conventional botany and agriculture, forestry and medicine, as they promote the study and preservation of biological diversity (Kuzevanov, Sizykh, 2005).

BASNINS FAMILY The founding father of this Irkutsk and Kiahta merchant family, famous in the 18th and 19th cc., was Maksim Basnin, a peasant from Kholmogory (or Velikiy Ustiug, according to some evidence). Engaged in commerce and, similarly to other tradesmen, attracted, on the one hand, by an itch for gain and, on the other hand, by the desire to see unknown lands, in the early 18th c. he settled in the upper reaches of the Lena River, in the village of Orlinga (one of the oldest villages of the Irkutsk Oblast, mentioned in the documents since 1658; now belongs to the Ust-Kut region).

His son Timofei ferried merchants’ goods along the Irkutsk-Yeniseisk route, and traded in furs and bread on the Lena. Even today, the cliff on the river against which broke the wooded barges of Timofei Basnin is called the Basnin Telka (cow). In 1789, he and his family moved to Irkutsk and joined the 3rd class of merchants, in which he remained to the end of his days; he owned three houses evaluated at 880 rubles. Timofei Maksimovich Basnin, member of the municipal court in 1793—1795, was the first in the family to start public service. Before his death, he made a will to his sons to the effect that they should live in the inherited house “by general consent and all together” and trade “hand in hand.”

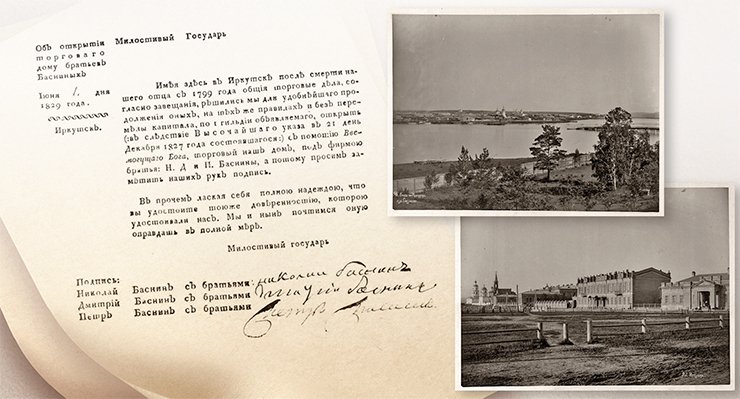

“Fulfilling his sacred will,” the brothers supplied provisions to various Siberian towns, traded in bread and fur, exchanged it for Chinese goods in the boundary Kiahta to be sold subsequently at the Nizhny Novgorod fair and in Moscow. In 1814 they registered as Kiahta merchants, and in 1829 started The N., D. and P. Basnin Merchant House in Irkutsk. The House played a leading role in the Russian-Chinese trade and was in business until mid-19th c., when the heirs divided the capital between themselves.

Among the Basnins brothers – intelligent, enterprising, ambitious, dynamic, and with broad horizons – the best-known and brightest personalities were Nikolai Timofeyevich and Petr Timofeyevich. The former was a 1st class merchant of Kiahta and Irkutsk, a commerce councilor, honorary citizen by birth (since 1834), head of the Merchant House, Burgomaster of the municipal court in 1805—1808, the elder of the Epiphany Cathedral in Irkutsk, and an art patron.

His interest in books (some of them, with the inscription “From the library of Basnin brothers merchants,” are kept to this day in the Academic Library of Irkutsk University) and in gardening (in 1834 he was one of the first in the city to lay out a garden) became a passion of his son Vasily Nikolayevich Basnin (1799—1876), a well-known representative of this merchant family, who went down in the history of Irkutsk.

In the early 19th c., the Russian Empire officially had two botanical gardens, called imperial, one in Moscow and the other in St Petersburg. At that time, the east of the country had no gardening structure that could pretend to be referred to as a “botanical garden,” a definition implying a certain degree of publicity, though some successful private horticultural businesses were in place.

A country without gardens

In the 18th c., European Russia featured three main types of cultivated landscapes: home gardens, having a practical and commercial function; botanical (“state”) gardens, originally called to be scientific and educational centers; and public gardens (parks), meant for recreation.

As new settlements were arising in East Siberia, fruit and vegetable gardens were mainly laid out next to churches and monasteries. Local inhabitants would have small kitchen gardens but these were not of great importance because wild-growing berries, nuts and edible plants were abundant and easy to gather. Rare experiments on growing fruit and decorative plants did not have much influence on the situation, and attempts made by a number of municipal governors to beautify their towns, like Irkutsk, were fruitless because their population took them as an onerous duty (Andreyeva, 1958).

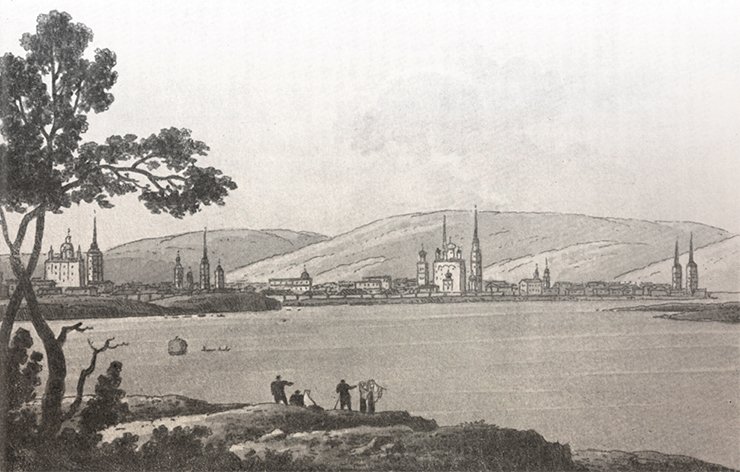

However, by the late 18th and early 19th cc., the situation in East Siberia was changing: the population grew, the layer of educated people in different social classes increased, gold mining was thriving, and the role of Irkutsk as the capital of the Irkutsk Province and the main route for trading with China became more important. It should be added that the Irkutsk Province of the time covered a vast area stretching to the east of the Yenisei Province up to Alaska and Northern California; it included East Siberia, Russian Far East, Chukotka, Kamchatka, and the north-west of America.

My great grandfather BasninIt is not known whether the first Basnin was handsome or just bright red in memory of Europe’s Celtic past; what is known is that he was deft and dashing. He bravely left his native Kholmogory in the early 18th c. and headed for Siberia with a gang of daring people. The name of this young man was Maksim, and the nickname was Basny. He settled on the Lena River, got married and began ferrying goods along this greatest of the world’s rivers. Out of his children, Timofei was the one who succeeded in goods transportation. His smartness and enterprise laid foundation for the future richness of the Basnins’ family.

Being very well aware that “money makes money,” Timofei Maksimovich nonetheless stuck to his father’s motto, which he bequeathed to his children: “Get richer in praise of God.” “Remember,” told Maksim to his son Timofei, “treasures are not money but good deeds done for the sake of God.” To us, pragmatics, who hate all kind of pathos, these words addressed to conscience evoke no trust but they make understandable the love of the first Basnins for reading and collecting spiritual books and notes. All the Basnins seem to have kept in their souls this behest of their predecessor Maksim.

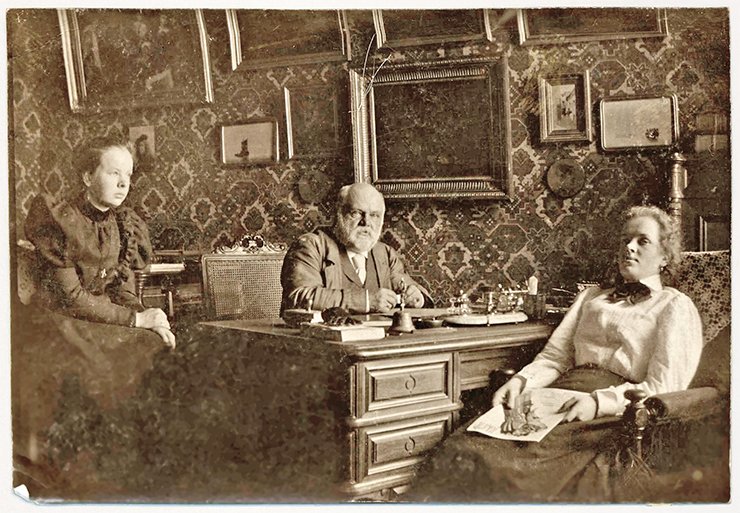

All the Basnins’ characteristic hereditary features focused in Nikolai Vasilievich’s father, Vasily Nikolayevich Basnin: deftness, good looks and luckiness, permanent drive for self-education, an observing and ironic mind, the Old Testament understanding of fairness, musicality, love for books, drawings and engravings, and love for gardens and greenhouses.

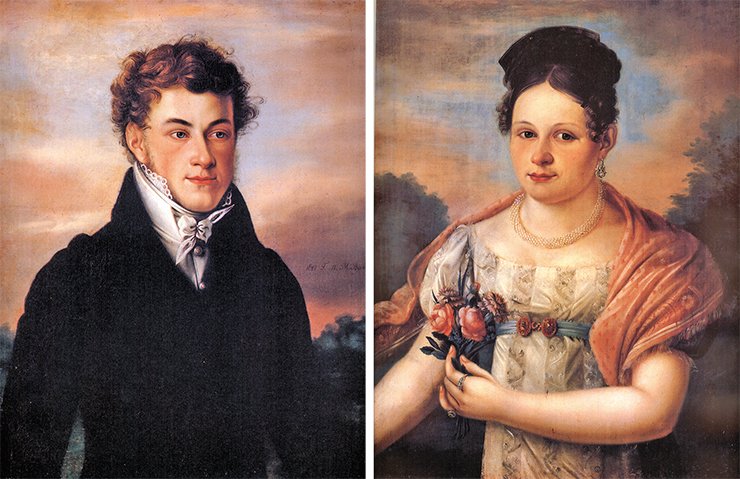

In my youth, I saw the portraits of V. N. Basnin and his wife, painted by the Irkutsk artist Mikhail Vasiliev in 1821. Until 1955 they used to hang on the walls of S. N. Basnina’s rooms. Let me note that even nobility often ordered their family portraits to bondsmen rather than to professional artists, to say nothing of merchants who couldn’t order a portrait from Lampi. The merchant family portraits lack a proper perspective, the palms are not well drawn but, surprisingly, the head is almost always built ideally, the eyes are artfully placed in the orbits, and the ears are well-shaped and occupy a proper place with respect to the cheekbone. The similarity is striking, almost that of Velásquez. These primitive paintings are so expressional that smooth Brullov looks awkward by comparison. In Vasiliev’s portrait of V. N. Basnin we can see a dapperly dressed young man, so attractive that we could compare him to Eugene Onegin. His face is serene, as it often is with handsome and lucky people. The similarity to the original causes no doubt, and a proof to it are the photographs of his children taken by Carl Mazer, a Swedish painter who made a trip to Siberia.

V. N. Basnin’s young wife, Yelizaveta Portnova, portayed by the same Mikhail Vasiliev, looks astonishingly innocent and kind-hearted. Her face is that of a peasant girl, despite the nobility-like hairdo and dress cut, with the waistline right under the chest. If we look at the photographs of the couple taken during their life in Moscow, we’ll be struck by the expressions of resentment or even bitterness, and a look of distrust in their eyes. How life presses the soul! How many disappointments and lost hopes! Vasily Nikolayevich was tired of trade, which he never liked deep in his heart. His frictions with Muravyev, East Siberia’s General Governer, seeem be be nothing but an excuse for disposing of the business and leaving Irkutsk. He couldn’t put up with Muravyev’s cruel policy towards the Chinese. Vasily Nikolayevich remembered well his youth, when he was in charge of the Kiahta trading house. The Chinese merchants took a liking to the sharp and good-looking Russian. Va Sin Ka, they used to call him lovingly.

And what about Yelizaveta Osipovna, why does she look so stern? She is the mother of eight, which was not a heroic deed at the time. Only two sons out of the eight are alive: Ivan and Nikolai the younger. The older Nikolai, a dragoon, perished in the Crimea, during the battle of Kuriuk-Dare.

Let us go back to the portraits on which the spouses are still young, charming, and full of hope. In 1828, V. N. Basnin took a trip to St Petersburg. In his letters, he shared all of his impressions with his young wife. The language in which these letters are written is as provincial as the portraits by the talented citizen of Irkutsk Vasiliev. Ostrovsky could have easily used this kind of wording in his comedies: “Istomina, years ago as light as Zephyrus, is now filled by the goddess of health to the degree that makes her dancing less enchanting; however, as far as depiction of passions is concerned, she is different from others...”

All of Basnin’s letters posted to Irkutsk and written to the young wife were intended to be read in the family circle, which explains the somewhat elevated phrasing. And yet, the colorful language more than makes up for all the provincialisms: “Yesterday, till late at night, I was standing on the Isaakievskiy (Saint Isaak’s) Bridge: a ship was being launched. How curious it is to look at this mammoth of a boat, which will soon carry the threat and power of Russian arms to the ocean waters. There is another ship built at the Admiralty shipyard, much superior in size to the first one. Without seeing them, it is impossible to have a true idea of how colossal these horrible floating houses are...”

Not commenting on the well-known connections between the Basnins and Decembrists, I would like to highlight a remarkable trait of V. N. Basnin’s character – his love for natural science. He was the first to acclimatize European and exotic fruit trees and plants to the harsh conditions of Irkutsk. Everybody could get cuttings and seeds from his garden, which soon turned from private to public.

The citizens of Irkutsk had easy access to his rich library, and I still use the Dictionary of Painters and Engravers, published in Zurich in 1779, that used to belong to him. The dictionary was published in German in a complicated Gothic face, and on the pages with the biographies of quite a few engravers there are pencil notes left by my great-great-grandfather...

From: (Time Link: The Basnins in the History of Irkutsk, Irkutsk, 2008)

The first “public botanical garden,” the largest plant collection to the east of the Urals, was set up in Irkutsk by a member of an Irkutsk merchant dynasty, V. N. Basnin. In 1829, the Basnins (Basniny) ranked among the wealthiest merchant families of Kiahta and Irkutsk. At the time, only enthusiasm of such wealthy people as Basnin could afford to collect very expensive things, out of reach of ordinary citizens. In contrast to other dwellers of Irkutsk, they were not only able but also willing to keep, in costly greenhouses and orangeries, plant collections unique for the region – all the year round.

Let there be a garden!

Vasily Basnin first got acquainted with European horticulture and with the Moscow and St Petersburg botanical gardens quite early: at the age of twelve he completed his “home education’” and began helping his father with the tea business, taking part in “commercial trips across Siberia” and Russia. This was the time of transforming and renovating the “apothecaries’ gardens” founded by Peter I, which came to be called “Imperial botanical gardens,” after the European manner.

Basnin’s botanical interests formed and developed under the influence of a young finance officer, State Counselor N. S. Turchaninov, who moved in 1828 from Moscow to Irkutsk to work for the Ministry of East Siberia General Governor. The matter is that this graduate of Kharkov University, awarded with the degree of a Candidate of Physics and Mathematics, devoted all his free time to...botany. Turchaninov got interested in going to live and work in Siberia thanks to F. B. Fischer, director of the St Petersburg Botanical Garden. It was Fischer’s dream to start a new botanical garden in Siberia, and Irkutsk was the supposed location (Gaponenko, Aseyeva, 1996).

In 1821, Fisher wrote in the “Project of Forming an Economic-Botanical Garden in Siberia”, published in the Zemledelchesky zhurnal (Agricultural Journal): “ Siberia lacks for good fruit trees, and the fruits themselves are not being improved in this land, which could be achieved through good gardening. In many locations of Siberia, the climate is not as harsh as people think by prejudice; and this is why it needs a well-organized horticultural establishment, where plants precious for this land could be grown and adapted to the climate... This is my plan on this subject. The plan that is to be followed in establishing an economic-botanical garden in Siberia does not differ much from that of similar establishments for any other country. There should be two objectives. The first is to grow all plants, adapt them to the climate and distribute all the plants that can be useful, in this or that respect, for Siberia. The second objective is to grow the plants typical of this land so as to send them to all European gardens and to receive from them new products, according to a regular exchange plan... The geographic situation of Irkutsk and its climate is less harsh, and owing to various locations, the garden can have special conveniences. The chief gardener can be booked in other lands...and supplied with two assistants, knowledgeable and skillful people, who would alternatively travel across Siberia with a view to gathering plants for the garden’s use and growth’” (Gaponenko, Aseyeva, 1996, p.168).

In 1821, Fisher wrote in the “Project of Forming an Economic-Botanical Garden in Siberia”, published in the Zemledelchesky zhurnal (Agricultural Journal): “ Siberia lacks for good fruit trees, and the fruits themselves are not being improved in this land, which could be achieved through good gardening. In many locations of Siberia, the climate is not as harsh as people think by prejudice; and this is why it needs a well-organized horticultural establishment, where plants precious for this land could be grown and adapted to the climate... This is my plan on this subject. The plan that is to be followed in establishing an economic-botanical garden in Siberia does not differ much from that of similar establishments for any other country. There should be two objectives. The first is to grow all plants, adapt them to the climate and distribute all the plants that can be useful, in this or that respect, for Siberia. The second objective is to grow the plants typical of this land so as to send them to all European gardens and to receive from them new products, according to a regular exchange plan... The geographic situation of Irkutsk and its climate is less harsh, and owing to various locations, the garden can have special conveniences. The chief gardener can be booked in other lands...and supplied with two assistants, knowledgeable and skillful people, who would alternatively travel across Siberia with a view to gathering plants for the garden’s use and growth’” (Gaponenko, Aseyeva, 1996, p.168).

According to Fischer’s design, the State Counselor from the capital was meant for the director of the Economic-Botanical Garden. During many years, Turchaninov, using his own means, made trips in the vicinity of Irkutsk and along the southern bank of Lake Baikal, exploring the flora of Cis-Baikal and Trans-Baikal regions. Elected in 1830 a Corresponding Member of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, during five years he performed the duties of a “scientist-traveler between Altai and the Eastern Ocean” (Lipshitz, 1964).

It was this botanist of highest qualification that gave the idea of a “botanical garden” to the young merchant. In the letters to his relations in Irkutsk, written in 1828, Basnin described ethusiastically his first, unforgettable impressions of visiting the Imperial Botanical Garden in St Petersburg. “This day I will never forget! ‹…› but my strongest impression was the plant collection in Fischer’s botanical alleys. What gigantic plants! What diverse form nature has given to many of them! Regretfully, I was struck only by the novelty of these objects, and not by their rarity, of which only the botanists are aware.”

Summer all the year round

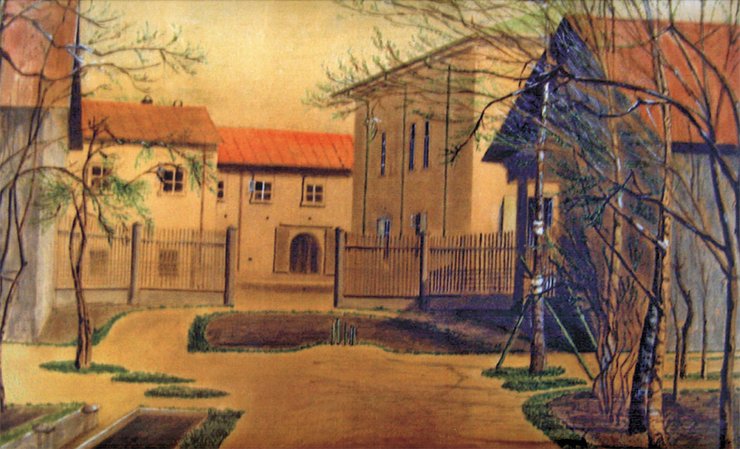

The garden at the Basnins’ mansion was laid out for the personal needs of the large family by Vasily Basnin’s father, Nikolai Timofeyevich, back in 1834. His son became actively involved in developing the garden: he planted a great many trees, bushes and flowers on open spaces, and built big greenhouses and hothouses.

He was the first not only in Irkutsk but in all East Siberia to acclimate fruit trees on a large scale, grow a wide diversity of flowers and exotic plants in great numbers, and not only in greenhouses but on beds as well. This is why he is considered the initiator of popular gardening in the Baikal region, even though before him, in the late 18th c., some attempts had been made to set up greenhouses for growing subtropical plants in the conditions of East Siberia.

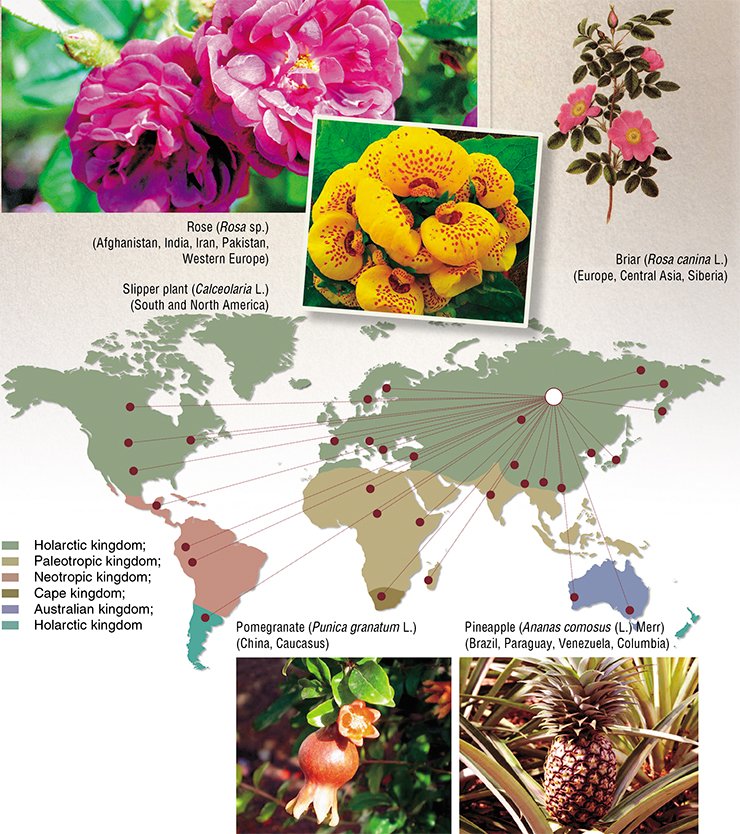

To increase his collections, Basnin gathered plants from all over the world. During many years, he communicated with Fischer: Basnin and Turchaninov sent to the Imperial Botanical Garden seeds and herbaria of Siberian plants and received seeds of exotic plants in exchange. A lot of plants were booked from other places in Russia and in China.

Regretfully, the original drafts and specific plans of the garden plots and greenhouses have not been preserved. Today, we can reconstruct the plan of the Basnins’ Garden only basing on the notes of Basnin himself and disparate memoirs of his contemporaries.

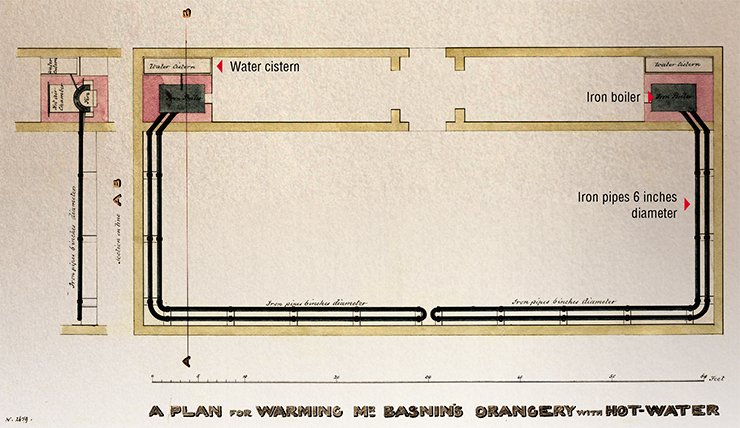

Covering over half of Basnins’ estate, the Basnins’ Garden had a large system of greenhouses comprising three interconnected glass houses and hothouses with a total length of 70 meters and width of 10 meters (Selskiy, 1857). The garden itself, where open-ground plants grew, occupied no less than 5,000 m2.

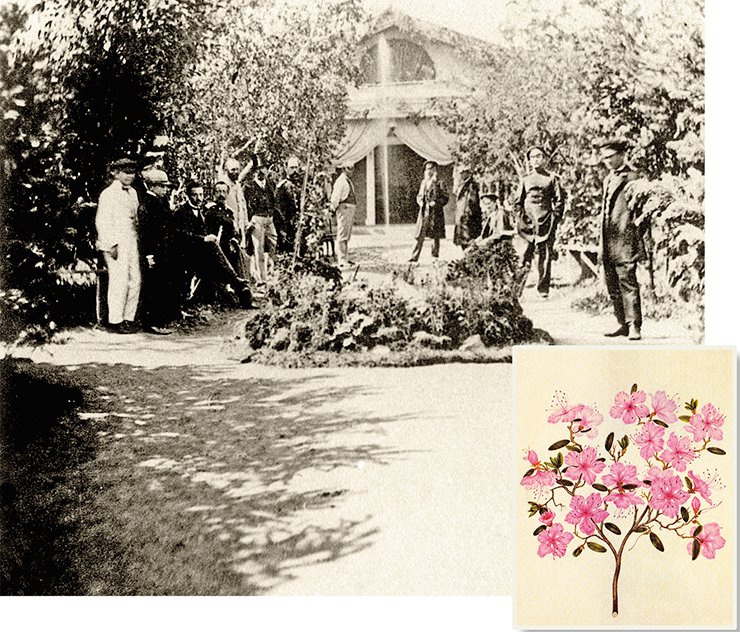

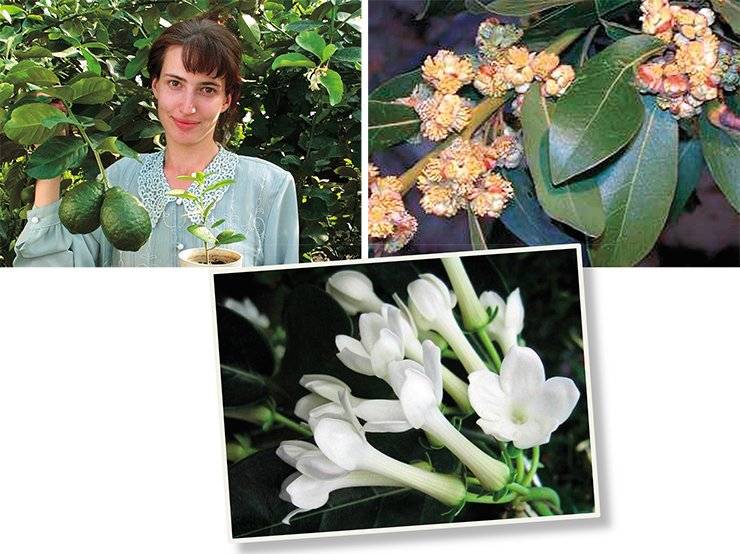

By and large, the Basnins’ Garden met the criteria of a botanic garden as it represented a documented collection of plants with labels in the Russian and Latin languages. At the same time, it was a favorite recreation ground of Irkutsk citizens, attracting a lot of strollers, especially nannies and kids (Selskiy, 1857)According to the memories of Irkutsk citizens, the greenhouses were a great piece of work and were kept in perfect order: the visitors were impressed by the immaculate cleanliness and “artistic” arrangement of plants. The greenhouses themselves contained a special hall for the so-called flower exhibition, where Basnin put the best plants in blossom. In the fruit greenhouse, peaches, apricots, pears, apples, cherries, lemons, oranges, grapes, and other fruits ripened (Andreyeva, 1958).

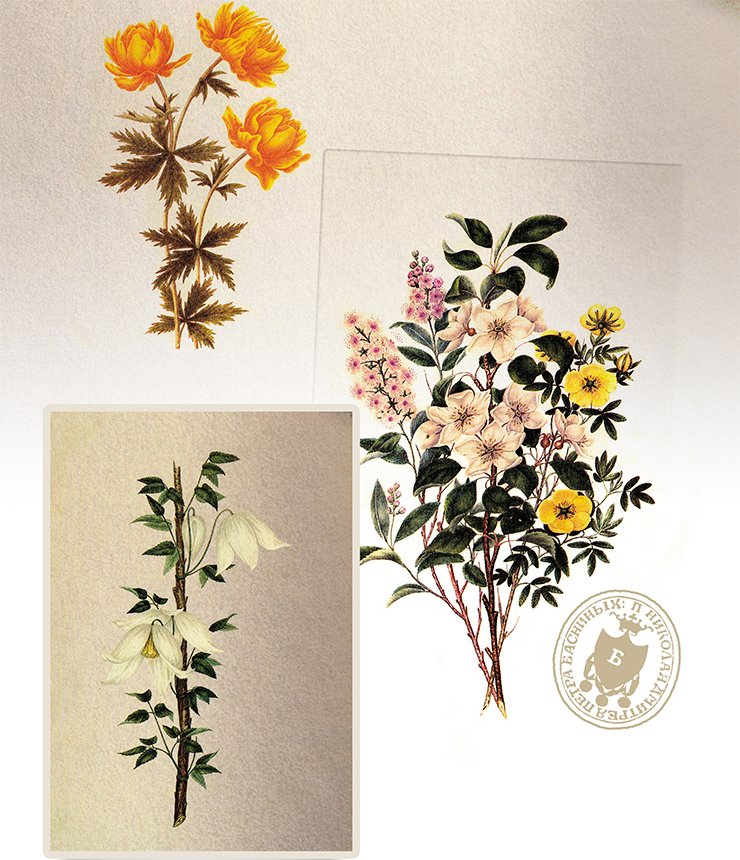

Here is Basnin’s description of a greenhouse in the early April 1856: “In the ample flower area it is luxurious summer. ‹…› 42 species have come out. Wonderful old roses, lilac, amaryllis, rhododendrons, double-flowering cherry and peaches, Chinese dicentra, azalias, and so on.” In the letter of August 24, 1857 to his son Osip: “Take, for instance, the view of a few hundred colossal dahlias blossoming at the same time; one of the plants was over a sazhen’ (two meters) high, over an arshin (28 inches) and a half in diameter and had 60 open flowers and another 60 buds.” A lot of interesting details can be found in Basnin’s special Garden Diary, having six volumes: “On Ilya’s Day (August 2) we had the first pineapple in this summer. And then ripen apples, pears, and plums...peaches and grapes should come later. We will have melons, cucumbers, radishes, and greens constantly, beginning with March” (quoted from: Manassein; p. 19, 22).

The diversity of the living collections Basnin gathered from over 120 local and exotic species of all the continents astonished the contemporaries: it had no analogues in Siberia, whose cold and harsh climate, as it seemed, made the idea of growing warm-loving and tender exotic plants absurd.

The diversity of the living collections Basnin gathered from over 120 local and exotic species of all the continents astonished the contemporaries: it had no analogues in Siberia, whose cold and harsh climate, as it seemed, made the idea of growing warm-loving and tender exotic plants absurd.

Everybody interested could buy flowers and seeds from Basnins’ Garden, and the garden was visited not only by the citizens of Irkutsk. Judging by the list of plants from the Basnin’s garden archive (camellias, passion fruit, hibiscus, ivy, fuchsia, lemon, Seville orange, pineapples, cacti, etc.), the planting material for growing home plants, perennials and fruit trees might even have got to the Decembrists, who had been deported to Siberia and lived quite far from Irkutsk. It is not without reason that S. P. Trubetskoy wrote about his wife’s home orchard: “My Sashenka likes messing with flowers, and today she has, among others, good dahlias, beautiful heart’s ease, ‹…› all sorts of cacti, gloxinias, camellias, tuberoses, amaryllis...fuchsias” (Lagus, 1890, p. 9). In all likelihood, these plants, rare for Siberia, were dispatched to the Decembrists by their kind-hearted friend, V. N. Basnin.

Gardening becomes a job

In 1858, the whole Basnin family moved to Moscow. The garden was left to the care of their friend and gardening consultant, a highly placed officer of East Siberia Main Headquarters, I. S. Selskiy and gardener Karp, who, over the following few years, bore without fail the burden of keeping it. For example, the French traveler V. Menian, who visited Irkutsk at the time, was struck by the luxurious way of life of some of its citizens and by the abundance of exotic plants. “These gentlemen build huge stone palaces, fill them with Seville oranges, bananas, various tropical plants, which cost a fortune” (quoted from: Andreyeva, 1958; p.143).

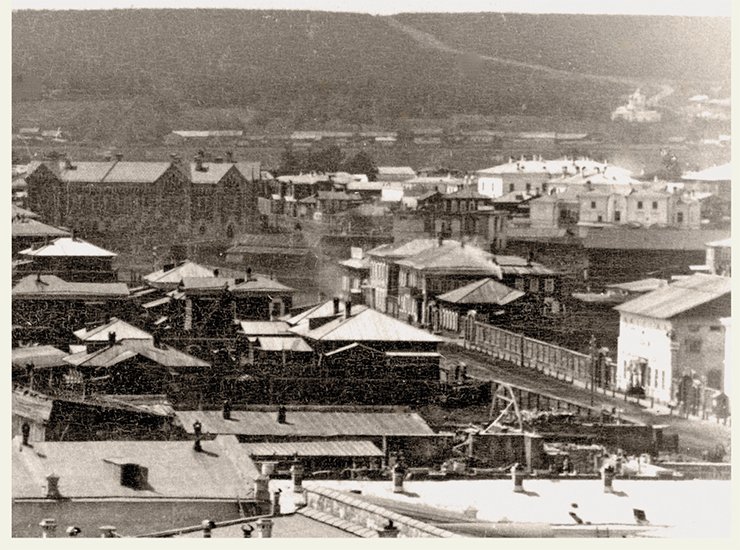

“Those who lived in Irkutsk or visited it 15 or 20 years ago,” reads the chronicle of 1857, “will not recognize it. Its population has almost doubled since. It is growing like a house on fire – both in width and upwards. Apparently, everything testifies that the city is becoming richer, gaining in importance, and it is turning into a true center, for East Siberia at least; its position on the great Siberian way is really among the most profitable, and it will never lose its role of the inevitable crossroads on this way” (Romanova, 1914, p. 356).

V. N. Basnin collected fascinating and unknown plants in the vicinity of Irkutsk and on the coast of Lake Baikal. One of the new species of water plants found by him was described by the well-known botanist N. S. Turchaninov as “Basnin’s nymph,” or Nymphea basniniana Turcz. In this way, the name of Basnin went down in history in the name of a beautiful water lily (Cherepanov, 1995). At present, this plant is usually referred to as white water lily (Nymphea candida J. et C. Presl.). Today, this rare species is listed in the Red Books of Russia, Irkutsk Oblast, Buryatia, and MongoliaIn 1868, the first flower and vegetable exhibition was held, participating in which were over 100 amateur gardeners. Since then, the exhibition was held annually and attracted thousands of visitors. Gardening was turning into a job: for example, according to the population census held in November 1878, “in Irkutsk there were 10 gardeners having an occupation and 4 without an occupation.”

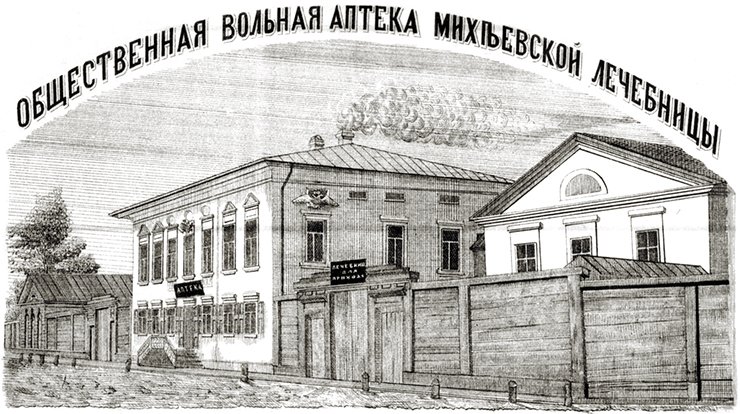

For ten years the Basnins’ Garden and estate waited for their owners to come back. However, Vasily Nikolayevich’s dream of returning to Irkutsk did not come true. The mansion had to be sold. The new owners set up the Mikheyev Clinic with a drugstore, and in 1870 added to it the Maak, Schmidt and Co Establishment of Artificial Mineral Waters.

The former Basnins’ Garden lived on though: it was open for visitors, music played a few days a week, and spaces for gymnastic exercises and games were organized. Several years later, the garden was closed for the public.

The Basnins’ Garden existed for about 45 years. Its unexpected and tragic end came in 1879, when a gigantic fire destroyed the central part of Irkutsk. There was nothing left of the garden – the fire ruined the greenhouses, and the unique collection of exotic plants was irretrievably lost

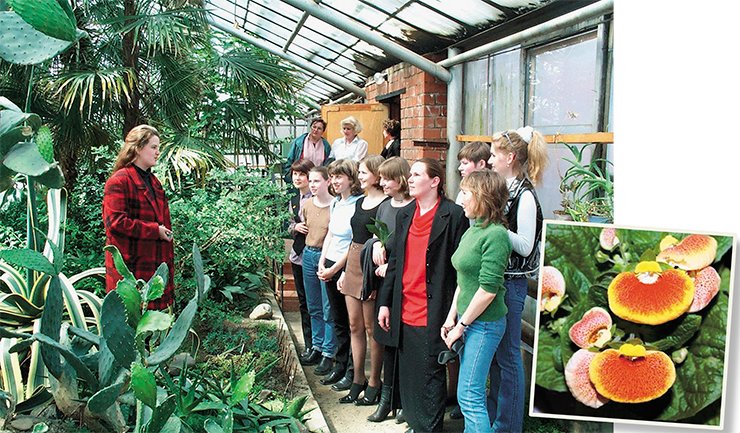

Over half a century after the Basnins’ Botanical garden was destroyed by the fire, the irkutsk Gorispolkom (Municipal Executive Committee) supported the initiative of setting up a new botanical garden, which was handed over to Irkutsk State University. After Basnin, this was the first successful attempt out of many to start a botanic garden in Irkutsk.

Today, this is the only botanic garden in Baikal Siberia which is a member of the Botanic Gardens Conservation International and has the status of a Nature Monument and a strictly protected area (Oldfield, 2007). In line with the Basnins’ traditions, the Irkutsk State University Botanical Garden has gathered and maintains a collection of over 3,000 plant species and forms, the biggest in East Siberia. In the Irkutsk State University Botanical Garden, over 750 species of arboreal plants from different corners of Siberia, Far East, Europe and North America have passed the test on climate resistance, and over 150 of them now grow in the towns of Baikal region.

The activities of the University Garden focused on mobilizing the genetic recourses of plants from the various places of the Earth allow us, similarly to the founding father, to enrich the region’s cultivated flora with new plants, important for the economy and ecology. The tradition of Basnins’ Botanical Garden is upheld by a constellation of East Siberian amateur gardeners, who enthusiastically test new plants in their apartments and dachas, hothouses and greenhouses, proudly calling themselves gardeners-experimentalists.

References

Andreeva R. A. Cvetovodu ljubitelju. Irkutsk, 1958.

Aseeva T. A., Surkova N. S. K istorii sozdanija botanicheskih sadov // Problemy introdukcii rastenij v Bajkal’skoj Sibiri… S. 18, 19.

Gaponenko V. V., Aseeva T. A. Sady Vostochnoj Sibiri v pervoj polovine XIX v. //Istoricheskoe, kul’turnoe i prirodnoe nasledie (sostojanie, problemy, transljacija). Vyp. 1. Ulan-Udje, 1996. S. 164–176.

Kuzevanov V. Ja., Sizyh S. V. Resursy Botanicheskogo sada IGU: obrazovatel’nye, nauchnye i social’no-jekologicheskie aspekty. Spravochno-metodicheskoe posobie. Irkutsk, 2005. 243 c.

Kujbysheva K. S., Safonova N. I. Akvareli dekabrista Petra Ivanovicha Borisova. M., 1986.

Polunina N.M. «Sovershennyj kupec» // Zemlja Irkutskaja. 1996. № 5. S. 62.

Svjaz’ vremen: Basniny v istorii Irkutska. / sost. S. I. Medvedev, E. M. Pospehova, V. N. Chebykina. Irkutsk: Irkutskoe otdelenie Muzeja svjazi Sibiri, 2008. 152 s.

Lipshic S. Ju. Zhizn’ i tvorchestvo zamechatel’nogo russkogo botanika-sistematika N. S. Turchaninova (1796–1863) // Botanicheskij zhurnal. 1964. T. 49. № 5. S. 5–24.

The author and editors thank Director of the Irkutsk Branch of the Museum of Siberian Communication V. N. Chebykina and well-known Irkutsk local historian S. I. Medvedev for their assistance with the preparation of the illustrations