Archaeology... in the War. Russian Scholars in Trabzon

In 1916, at the peak of the World War I, a group of Russian scholars found itself in Trabzon. Our researchers were traditionally interested in the history of Byzantium, the more so because Russia considered itself to be the historical heir to Byzantium. For the majority of the Russian historians the tastiest morsel for studying Byzantium was Constantinople, and the Constantinople of the time of its golden age (that is, before 1204, when the crusaders destroyed Byzantium). However, during the World War I our historians had to exercise their flexibility and to adjust their priorities. The reason for that was the intricate line of military operations, which resulted in Trabzon temporarily becoming a “Russian” city. Studying its memorials could provide unique material concerning the period of decline of Byzantium Empire...

In spite of Trabzon being one of the oldest towns in the world, it remained one of relatively remote provinces of Roman Empire for quite some time, marking its frontier in the Late Antiquity. The strategy of the Roman army there could be formulated in one phrase — to fight outer enemies with small forces. It led to creating a good road network that connected few and isolated garrisons. It increased the mobility of the army elements that could quickly move along the border to the most dangerous part of it.

But the Roman emperors did not show any particular interest in the land and seldom appeared there.

The newly born Trabzon “Empire” was first heard of after constitution of Latin Empire in Constantinople in 1204. The latter — a “splinter” of the great Byzantium — was threatened from every quarter. It failed to develop a strict centralization — Latin Empire did not manage to bring together even the centers of the Greek culture. In the circumstances Trabzon “Empire”, which got rid of the strict pressing by Constantinople, began its own isolated life absorbing the Byzantine acres in Crimea, which rendered it tribute. However, the Trabzon “emperor” was rendering tribute to Seljuqs being their vassals. There were some purely economic reasons for the appearance of the relatively independent Trabzon Empire. It was formed “around” the center of economic activity, where the commercial routes crossed that connected North Black Sea region and Transcaucasia and the regions of Asia Minor.

However, it is obvious that the very time limits of the existence of the Trabzon Empire prevented it from becoming a more or less reliable source of information on the early history of Byzantium. The majority of the buildings that survived and much of the “evidence” of Christianity (books and cult objects) belong to the period beginning with the last emperors of the Comnenus dynasty. The decorations and frescos of the Trabzon churches are dated by the decade immediately preceding the final fall of Constantinople in 1453.

The reason for sending the legendary Trabzon expedition of 1916—1917 was to study the relics of Trabzon.

Turkey, who became the ally to Germany and Austria-Hungary in the beginning of the 20th century, declared war on Russia when the operations broke out in Europe. Turkey held the key to the situation on the Balkans, which was of traditional interest to our country. Many factors played their role there — the traditional support of liberation movement of the Greeks and the Balkan Slavs, who were striving to leave the weakening embrace of the Ottoman Empire, and the urge to gain control over Bosporus and Dardanelles, which would open an exit from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, and the ideology of integration of all Slavs (“Constantinople must belong to us!”), and the long history of resistance...

Being the largest port in the east of Turkey, Trabzon was its most important strategic position. The Turkish army was replenished through it. Naturally, if the Russian army conquered Trabzon, it would lead at least to establishing Russian control over the part of the Turkish territory and would significantly weaken it (some even supposed that it might end by the complete defeat of Turkey). In January, 1916, General V. N. Lyakhov ordered to attack Trabzon. By April, 1916, the 15,000 Russian detachment was already near Trabzon. Here the attackers gained reinforcement by sea — two platoon brigades counting 18,000. The assault was short. The soldiers made a forced crossing of a rough cold river and with the fire support of the ships of the Black Sea Navy dislodged the enemy out of the trenches. On April 5 the Russian army entered Trabzon.

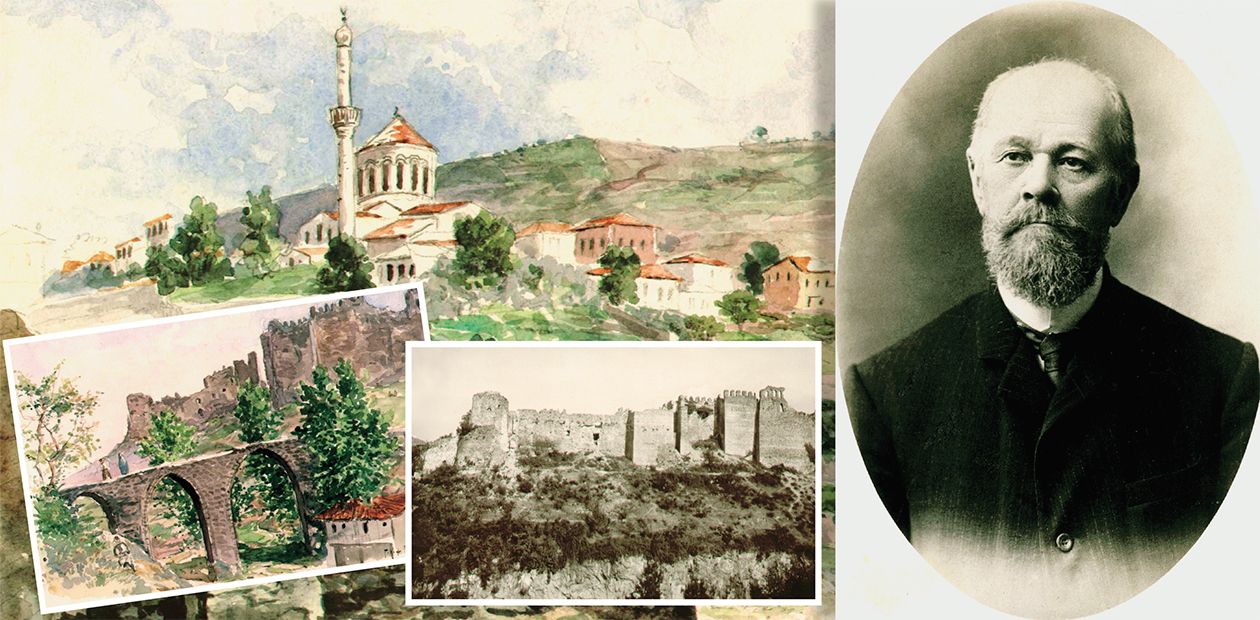

Some time later the town saw the scholars of the Trabzon expedition, whose aim was to study and keep the historical heritage on the territories belonging to Russia by right of war. At first its status was somewhat vague. The expedition was sent with the help of the funds of the Russian Archaeological Institute in Constantinople. Our only scientific institution abroad was established in 1894. Its permanent director was a prominent Slavonic and Byzantium scholar, Academician Fyodor Ivanovich Uspenskiy (1845—1928). Having broken off diplomatic relations with Russia in 1914, Turkey closed that institution. When the Russian army seized Trabzon, the employees of the Institute who found themselves out of work saw a new field of activity. For the sake of justice we must note that Uspenskiy himself considered the Trabzon expedition but a temporary occupation. He was convinced that very soon the Russian soldiers would march along the streets of Constantinople.

The academician’s attitude to studying and keeping the monuments of the Byzantium history in Turkey is clearly illustrated by his report to count P. N. Ignatiev, Minister for Foreign Affairs (which did not reach the addressee, though). He wrote it on April 18, 1916, two weeks after our army conquered Trabzon. Quote: “Dear Sir, Count Pavel Nikolaevich, considering that sending persons who were chosen by the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Russian Archaeological Society to go to Trabzon meets unexpected difficulty, as well as with regard to the fact that the meeting intended to resolve this issue causes severe damage to the very matter for the sake of which the sending was undertaken, I find it suitable to solicit you about ordering the director of the Russian Archaeological Institute in Constantinople to fulfill his duties on the Turkish front.”

The report shows that F. I. Uspenskiy thought that the Trabzon expedition was an urgent matter and that he supposed to involve the Russian Archaeological Institute in Constantinople, which left the town after the beginning of the war.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs took an active part in keeping the historical monuments on the territories under Russian control. It was a matter of “ideological” principle. In the war, which was called by the British and French newspapers the battle between the civilized countries and Teutonic barbarians, not only the army success counted. Creating a “civilized” image of Russia was of no less importance.

The Trabzon expedition was called “archaeological”. The name was partly nominal. Description and preservation of the ancient monuments occupied the first place, while the excavations were to be carried out only when possible.

There is a fragment of the draft report dedicated to the problems to be solved by the Russian scholars in Turkey. It shows Uspenskiy not so much as an outstanding scholar but as a politician with a point of view of his own. “With conquering Trabzon”, the academician wrote, “We have archieved a significant success in terms of politics. Here we have come in touch with the most disciplined political power possessing indisputable influence over the whole coastline of Anatoly. Besides, having entered Trabzon we got control over the empire capital, which had important political purposes and extensive mission.”

By the way, some phrases of the text show that the scholar knew (or guessed) about the existing plans on the territory division of the defeated Turkey and creation of an independent state with Trabzon as its center.

F. Uspenskiy went to Trabzon twice for rather long periods of time. The character of the scholarly works that he organized is seen from his report to the Academy of Sciences. In particular, it says that they “ascertained the historical and artistic value of three Christian churches converted into mosques: 1) St.Sophia, 2) Panagia Khrysokephalos, 3) St. Eugene’s”.

At the same time, Uspenskiy had to solve not only scholarly but also administrative problems in Trabzon. In his own words: “The matter went from the district head to the building squad and city council, all of which did not want to bear repair expenses, even though they had in their budgets a sum for protecting the monuments. To resolve the problem I said that I would pay the expenses from the funds of the archaeological expedition. Thus, the first-rank and unique monument, which the local Greek society could not but regard as their national property, was saved by the Russian funds from the threat of devastation! By my application the monument was fenced with iron grilles, delivered by the city council from their warehouse.”

They had to fight every step, and not always successfully. By 1917 the academician’s optimism began to decline rapidly giving way to understanding that in the given conditions the problem of keeping the cultural heritage could not be solved. Here is a quotation from a report by F. Uspenskiy about his trips to Trabzon, which he sent to the Academy of Sciences in 1917: “To the Special Transcaucasian Committee. I have the honor to ask for the attention of the Committee, whose state significance is becoming more and more evident for me as I go deeper in the matter incumbent on me by the Government. It is my second summer in Trabzon and its outskirts as I work with the archaeological monuments and take measures to their registration and protection as much as it is allowed by the martial law in the country and as far as the war concerns do not prevail over the archaeological requirements, more than once I was deeply embarrassed by the question: how shall we protect the objects of art, manuscripts, books, etc, from plundering and damage if the archaeological expedition has no keys to the monuments (first of all, the mosques converted from Christian churches). Moreover access to the mosques was opened to everybody in May last year and in June of the present 1917, because the doors in the mosques had been taken off (St. Sophia), there were no keys or bolts, though the doors were restored and the locks bought several times a year. The inevitability and repetition of forcing the locks and penetration into the mosques by removing iron bars at the windows of the mosques where the doors could not be broken, is a commom thing in Trabzon, as well as damaging, plundering and selling books and manuscripts and various art objects.” It sounds like a cry of despair, would not you agree?

After the February revolution the necessity to officially confirm the status of the Trabzon expedition arose. What had been done before owing to the authority of influential academicians, who were personally involved with the highest officials, now required “state” registration. In the beginning of March, 1917, the well-known archaeologist I. Ya. Stelletskiy was appointed head of the Archaeological Department of Governor-General of the Turkey Regions Occupied by the Martial Law.

But hard times were approaching. The fate of Russia was uncertain. The plans of the Archaeological Department were not destined to be fulfilled. The majority of the papers were stolen. It was a reason why a comparably small amount of materials on the expedition was left in the archives. In general it is plans and measurements of the churches, copies of wall frescos, photographs of Trabzon regions and its major points of interest. The manuscripts and documents, of which F. I. Uspenskiy and I. Ya. Stelletskiy cared so much, disappeared.

Pictures by G. K. Meyer are used in the publication