Franklin’s Gift to Catherine II

In the fall of 1779, disturbing news came to St Petersburg from Irkutsk General Governor F. N. Klichka that “unidentified” foreign vessels had been spotted near the Chukotka shore. Those were the ships of James Cook’s third expedition (1776—1780) returning from the Hawaii after the death of their captain. The Russian court took this information gravely, which was not surprising: at the will of history, Russia was to confront the most powerful seafaring nation of that time, England

In the fall of 1779, disturbing news came to St Petersburg from Irkutsk General Governor F. N. Klichka that “unidentified” foreign vessels had been spotted near the Chukotka shore. Those were the ships of James Cook’s third expedition (1776—1780) returning from the Hawaii after the death of their captain. The Russian court took this information gravely, which was not surprising: at the will of history, Russia was to confront the most powerful seafaring nation of that time, England

England conquered, developed and mapped Canada and the entire American continent rigidly and, naturally, without taking into consideration the interests of the Russian Empire. On the English maps, American lands discovered by the Russians got English names; many achievements of Russian geography were ignored or arrogated.

First direct contacts of Russian official representatives with Benjamin Franklin, ambassador of the self-proclaimed United States of America in France, were established because the ships of James Cook’s expedition appeared near the Chukotka shore.

The first “American doctrine”

In December 1779, Russian ambassador in France I. S. Bariatinsky informed Vice-Chancellor N. I. Panin: “By virtue of the order of your Excellency dated 11 October, concerning the report of Irkutsk General-Governor F. N. Klichka on the two ships that had appeared close to the Chukotka islands and were supposed to come from Canada, I had a private conversation with Franklin and asked him whether he had any information on what kind of ships those were and also whether he had a map of those seas and of the assumed route from Canada to Kamchatka. Franklin answered that, as far as he was aware, that route had not been found yet and, hence, there were no maps. He read, though, a certain Spanish writer (whose name he could not remember) who wrote about some vessels that had departed from Hudson Bay, which is above Canada, in the land called Labrador, and managed to reach Japan; he considered, however, such a route, even if found, to be arduous not to say impossible; about the ships mentioned he thought that they were either Japanese of belonged to Captain Cook, who had left England three years ago to go round the world.”1

The documents that became foundation of the USA independence were signed ot only by France, England, and Spain but also by RussiaWe can imagine the feelings of Catherine II, who was known to be an Anglophile and had even received generous sums as a gift from the English ambassador when she was a Princess.

But politics is politics. Relations with England cooled down, which was especially noticeable against the background of the warming up that occurred between Russia and France after the death of Louis XV. These events urged Catherine the Great to make the well-known Declaration on Military Neutrality, as early as on February 27 (March 9) 1780, which, in fact, opened for the USA the way to real independence. The Declaration meant so much for the young nation of “thirteen American states” that some time later the forth USA President James Madison called it the “American doctrine” and emphasized that the initiative Russian government had taken made an “epoch in the history of maritime law”.

Of remarkable importance for the American continent was Russia’s participation in other negotiations that lasted from the early 1780s to the Versailles Congress of 1783. Let us remind you that during the Congress the first global repartition of the world among the great powers took place.

Versailles peace

In September 1783, Anglo—French and Anglo-Spanish preliminary peace agreements were signed in Versailles, which stipulated, among many other issues, independence of the thirteen American states. The USA representatives, Franklin and Adams, were not formally admitted to this most dramatic phase of the Congress, which was England’s requirement. Importantly, the issue of the USA territory was settled by other countries through the mediation of the two empires—Russian and Austrian.

Surprisingly, it is now a little-known fact that the documents that became foundation for the USA independence were signed not only by France, England, and Spain but also by Russia. Almost forgotten is the evidence of the historian D. N. Bantysh-Kamensky, a relation of I. S. Bariatinsky: “On top of the many successful negotiations held by him [Bariatinsky] in Paris with their ministry, he, together with the Austrian ambassador, both acting as mediators, signed the peace agreement made in Versailles in 1783 on September 3 New Style between France, England, and Spain, and received portraits of the sovereigns of the three aforesaid states, strewn with large diamonds.”2 Note that the American representatives present at the Versailles Congress were supposed to be given “bonus” gold tobacco boxes with a miniature portrait of the English King George III strewn with diamonds but they declined the gift.3

On the same date in Paris the final peace agreement was signed between Great Britain and the USA—the final chord of the Versailles Congress. This time, on the English crown insistence, they did without the Russian—Austrian mediation but Franklin managed to emphasize the Russian role during this stage of negotiations, too.

This is how N. N. Bolkhovitinov described the final episode of the USA’s diplomatic recognition: “After the agreement was officially signed, B. Franklin ‘privately’ handed over its text to the Russian delegates, who considered it to be their ‘duty’ to present it to Catherine II. In connection with the end of the war in America, B. Franklin also sent to I. S. Bariatinsky for Catherine “The Book of the Constitution of the United American Provinces and a medal struck to celebrate their independence.”4

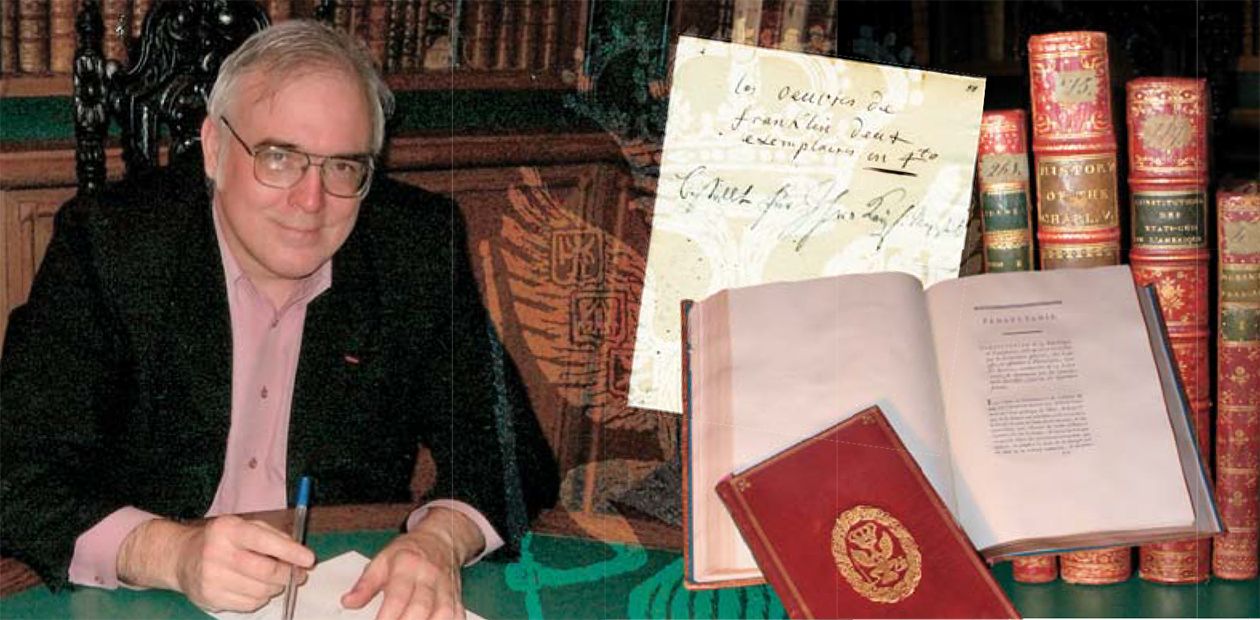

So we see that among the symbols of the USA independence marked in diplomatic papers and letters dating to the Versailles Congress, alongside texts of the agreement, medal to honor the USA’s independence, and official gifts to the ambassadors, was an edition of the USA Constitution published by Franklin in 1781 in the English language and in 1783 in the French language.

It is our good luck that the book sent by Franklin to Catherine II in September 17835 has been preserved in the archives of the Russian National Library, where it came from the Hermitage Library, or, to be more exact, from the Empress’s room library.

Constitution bound in red morocco

The Book of the Constitution of the United American Provinces Catherine received as a gift is bound in red morocco leather, and press gilded in the style of French binders of the time. In the center of the binder is an imprint of the Russian Imperial coat of arms framed in a wreath. The back side of the binder has numerous library codes beginning from the first code of Catherine II room library (584 a.) put by the Empress’s personal librarian A. I. Luzhkov.

The book’s binder deserves special attention. Such binders with coats of arms imprint were found on the several dozens of Paris publications of the 1770s—1780s, which made part of the Russian Empress’s personal collection.

This allows us to advance a few hypotheses on their origin. The first and simplest one is that the books passed over to Catherine II via the Russian ambassador in Paris were bound there by a privileged master.

This may explain the complete identity of the binders of The Constitution of the Thirteen American Provinces and French Monarchy by Chabri, also issued in 1783 and presented (with a dedication) to Catherine II. On Chabri’s book the two-headed eagle has no decorative frame but it is evident that the master used the same binding stamp.

The second and less probable but possible hypothesis is that the books were bound in Russia, at the Hermitage Library. Other interpretations cannot be ruled out either: for instance, in the late 1720s Peter the Great’s binding coat of arms (depicting the two-headed eagle and imperial regalia) was handed over to the Amsterdam publishing company of Janson Weisberg. Sometimes they would send books for binding from Petersburg to Holland, especially if the publications were intended as gifts to imperial persons. Several such books are kept in the Rare Books Archive with the Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St Petersburg, and in the Russian National Library.

Going back to Catherine II, let us note that Franklin sent her The Book of Constitution in French as she had a perfect command of this language and, in all probability, preferred it to English. At any rate, at about the same time she ordered to purchase for her the two-volume Collection of Works by Franklin, and the “highest” order kept in the Romanovs’ files6 directs to purchase the French edition of the American philosopher and statesman.

Catherine II used to read Franklin and appreciated him; she shared many of his political views. It goes without saying that we do not mean his democratic slogans or anti-monarchist provisions of the Constitution of Pennsylvania but his general philosophical ideas concerning religion and natural sciences. Many postulates of his philosophy reminded her of the deceased Voltaire, her loyal correspondent and mediator in literature and politics.

1 Quoted from the book by Bolkhovitinov N. N. “Russia and USA’s war for independence.1775—1783”. Moscow, 1976. — P. 29.

2 “Dictionary of memorable people of the Russian land”, Part 1. Compiled by Bantysh-Kamensky D. Moscow, 1836.—P. 198.

3 Pleshkov V. N. “Benjamin Franklin–the first American diplomat” // Filosfskiy vek. Almanakh 31. St Petersburg, 2006.—P. 32.

4 Bolkhovitinov N. N. Same source. Pp. 84—85.

5 Constitutions des treize Еtats-Unis de l’Amеrique a Philadelphie et se trouve a Paris. Chez Ph.-D. Pierres, Imprimeur Ordinaire du Roi, rue Saint–Jaques; Pissor, per&fils, Libraires, quai des Augustins,1783. The text was translated from English into French by Duke Louis-Alexandre De La Rochefoucauld d’Enville (1743—1792), French politician, member of the Paris Academy of Sciences, who corresponded with the Petersburg Academy of Sciences and E. R. Dashkova.

The book was referred to in the paper by S. V. Korolev “French books with Catherine II’s coat of arms from the former Hermitage Library” (Cahiers du Monde russe. 47/3. Juillet—Septembre 2006. Pp. 659–666). Regretfully, the scholar did not make the connection between this book and the history of Russian-American relationships.

6 The Russian National Library, Manuscripts Department, Archive 650. The Romanovs. Imperial Home N. 432. Leaf 5. I express my gratitude to B. A. Gradova, keeper with the Manuscript Department, for the information she kindly provided.