Knights of the Round Table

In the middle of the 20th century the profession of a nuclear physicist was regarded as romantic as that of a test pilot or a sea captain. The public’s attitude to nuclear physics was vividly illustrated by the cult film of the 1960s “Nine Days of One Year” featuring A. Batalov. If you pay a visit to the Akademgorodok Institute of Nuclear Physics, you can meet the legendary heroes of the physics’ «golden age» and see its young researchers

— The Institute of Nuclear Physics (INP) stands apart from other research institutes in many ways, including continuity of generations. You have lots of talented young people, which is quite extraordinary for today’s Russian research community used to the brain drain and to the outflow of young specialists to business and other non-academic fields of life. How did you manage to do it?

— To begin with, I’ll tell you a story. Some twenty years ago, at a meeting of the Presidium of the Siberian Branch of RAS, a distinguished academician (whose name I’ll omit) accused our Institute (read me) of being “a capitalist island amid the sea of socialism.” Seven years later, in 1993, the same person came forward with exactly the opposite accusation, “You live in a socialist society!” The funny thing is we have not changed — as far as our principles are concerned. It goes without saying that the situation in the country and in the world has been changing, and we, being an open system, did not escape the effects.

Indeed, the younger people coming to the Institute did not leave, at least not in high numbers. We had some losses, but not as big as those suffered by other institutes of the Academy, of the Ministry of Atomic Energy, and of other ministries… And now our Institute is the largest in the Academy, the second largest one being only half of the INP’s size.

From the beginning, we employ only good students. Formally they come here in their third or fourth year, though in fact we start looking for good researchers much earlier. INP’s researchers teach at Novosibirsk State University, Novosibirsk State Engineering University, and the College of Physics and Mathematics. Note that they teach not only majors, who have already made a choice of disciplines they’ll study in depth, but also University and College freshmen.

In Akademgorodok, this used to be a normal practice and did not require any special efforts from us before 1991. From that year on, however, salaries of the Institute’s research workers started going up, whilst those of University professors were going down. In a couple of years, the Universities lacked lecturers and professors for both junior and senior students. I made a suggestion that a researcher teaching at the University get for his teaching half of his INP’s salary instead of what the University was ready to pay him.

— In fact, you assumed the state’s function to support education?

— We did, and in more than one way. When we raised salaries to our researchers, the problem was solved. Of course, conflicts happened from time to time: one was good at teaching, and another wasn’t; one was invited to teach, and another was not… But the main thing was that our researchers did not reject teaching any longer.

Another action aimed at supporting education is more intensive financial backing of students, which we try to do from the earliest stage possible. We have established two special prizes of our own, the Budker Prize and the Sakharov Prize, which are awarded to eight students every year. Our Institute has always paid students coming to INP to do their pre-graduation practice. Apart from this, we have now doubled the grants paid to junior students who are interested in working at INP in the future.

Let’s move on: a young man has joined INP after graduation. Three things become important for him. The first is his salary, which should be more or less decent. Of course, the young graduate can earn more abroad, while to make more money in Russia he’d have to change his occupation.

Second, he should be confident that he’ll be able to improve his living conditions in the not too far-away future. If the young man gets married and has children, the situation can become desperate. Over the years, the “housing” support we provided has taken various forms depending on the current situation and legislation. We gave interest-free loans, co-financed construction of apartment houses where our employees could buy apartments at cost. Now we are trying to build new apartment houses in Akademgorodok: we organized a non-commercial partnership of research institutes to obtain apartments at cost. Of course, we are not constructing them with our own hands, but there will be no commercial intermediary between the builders and us, no company which would make money on it.

And we do not focus our attention entirely on the young. It would be unfair to leave the older generation in worse conditions. This is why we have the so-called “chains”: We try to build the best housing possible in reason. A senior researcher gets a new, better apartment and leaves his old one to the Institute. He only pays, at cost, for the “extra” square meters. The apartment he used to occupy goes to another INP researcher, who also leaves his old apartment to the Institute. At the end of this chain is a young employee who gets a one- or two-room apartment. If necessary, the bank will provide a loan to buy the apartment. INP guarantees to the bank the repayment of the loan and partially pays the interest. This scheme is quite complicated, and it became possible thanks to our good partnership with Sibacadembank.

And the third thing — probably the most important for our young men — is to be able to do world-level research. It is very difficult to keep up to this level. I’ll tell you about the structure of our budget, and you will see that we get very little from the state. Last year, for example, the basic budget financing that we got, as a research institute, from the Siberian Branch amounted only to 22—23 % of our total budget. The rest we earn in different ways. Our main earnings, about 80 %, come from abroad. How does it happen? About two-thirds we earn by participating, on a contractual basis, in international and national research projects. These contracts then turn into hardware, electronics, and optics. For example, nearly all of the world’s centers of synchrotron radiation use the equipment developed and made by us.

— And how long has the state financed only one-fourth of your Institute’s needs?

— Quite long. Since budget financing has been increasing, our salaries have been going up too. We must raise salaries because we are in strong competition with information industries and production. When production goes up a little bit, we have to increase salaries too to prevent the outflow of specialists.

Generally speaking, we do our best to raise our employees’ salaries regularly, and on a differential basis. The one who works better and contributes more to the project gets more. On the other hand, we believe that the salary should not depend on whether you are working under a contract or your job satisfies the Institute’s internal needs, though the latter does not make money directly: even if it gets the government’s funding, this share is very small.

It goes without saying that we place a special emphasis on our contractual work as it requires that we fulfill our obligations in terms of deadlines, quality, etc. In many years, we have acquired a fairly high rating — the world community knows what we can do. We participate in some very large projects, for example, in the construction of the LHC (Large Hadron Collider) in CERN, for which we provide the equipment.

This project, costing a few billion dollars, is truly global. CERN’s official members are a number of European states. However, all countries whose R&D is at a high level, such as the United States, Japan, and Russia, participate in the project; even though, formally, they are not CERN’s members. This is going to be the largest laboratory not only in nuclear physics but in the world. In terms of modern pure science, this project is the largest.

The LHC is a huge structure in the shape of a 30 km ring stuffed with some very high-level equipment. In the last ten years, we have provided to the Center equipment costing about a hundred million dollars, which made up a substantial share of our financing, about 25 %.

— Not a small amount… And where did this money come from?

— Well, it’s a different and quite a long story. In the beginning of the 1990s, it became clear to me as well as to all my colleagues working in the field of high energy physics that the only chance for Russia to remain in the vanguard in this area was to become an equal member of the LHC project. No need to say, our government could not afford to invest over 100 million dollars of its budget in CERN, as other countries did. Then I came up with an unconventional plan of Russia’s participation in the project, which was sure to satisfy all the parties interested.

The gist of this plan is as follows: Russia supplies high-tech research equipment whose cost, in world prices, is 150 million dollars. Russia’s research institutes — contractors agree to make it for 100 million dollars, which they obtain, in equal parts, from the budgets of CERN and Russia. In this plan everybody wins: CERN gets the equipment for $ 100 million “net” as Russia’s contribution in the project; Russia pays only $ 50 million for its participation in the most ambitious research project of our days and supports, with the same money, its own research institutes; and the Institutes get good money and guaranteed participation in the future experiments to be carried out at LHC. Despite the obvious pluses, virtually nobody believed that the plan would work. It seemed impossible that in 1994 we could agree about what we would do in Russia in the following ten years, at the beginning of the 2000s and, what’s more, using such a sophisticated financial structure.

It took me two years to explain that the plan was beneficial for them, for us, and for the whole research community. The Ministry of Science gave us its support. We organized a Russia-CERN Committee consisting of CERN’s five top executives and five members from Russia: director of the Ministry of Atomic Energy, three representatives of research community, and the Minister of Science as chairman. As a result, the CERN Council made a special resolution to finance our work. (European colleagues asked reasonable questions: why cannot their centers, their institutes, and industries do this work?).

The plan (referred to as “Skrinsky’s plan”) proved workable. By the way, in all these years the Ministry of Science has received no similar proposal from other research fields.

— Your ability to organize seems amazing, the more so that you’re a physicist and not a businessman or a manager…

— In fact, INP learned to earn money some time ago (it was not for nothing that we were accused of capitalist ways). It is just that back in the Soviet times the share of the money we earned did not exceed a quarter of our total budget. The money-making activities were initiated be G. I. Budker, who managed to obtain Kosygin’s* approval to supply our equipment to customers at market prices. In the Soviet Union, there were dozens of accelerators made by us that had various technical applications; some of them are still in operation.

Thus, the money-making principle was laid down ages ago. It is evident, though, that it wouldn’t have continued to work on its own, without our support. In fact, raising additional financing is not only my concern; all leading INP’s researchers, heads of laboratories, etc, are involved in the process… And we don’t have to make any superhuman efforts to achieve this; it is just that the Institute’s top positions — not only those of chief executives but any leading positions — have always been occupied by people for whom the Institute is something that really matters.

Today, most research institutes have split into many small teams. This year, for example, one of these teams has a contract and another doesn’t. As a result, the former gets a salary many times higher than the latter, financed only by the state. In other words, the former team has a lot whilst the latter falls apart or stops doing any work. Next year, however, the situation may reverse and the result will be deplorable for everybody.

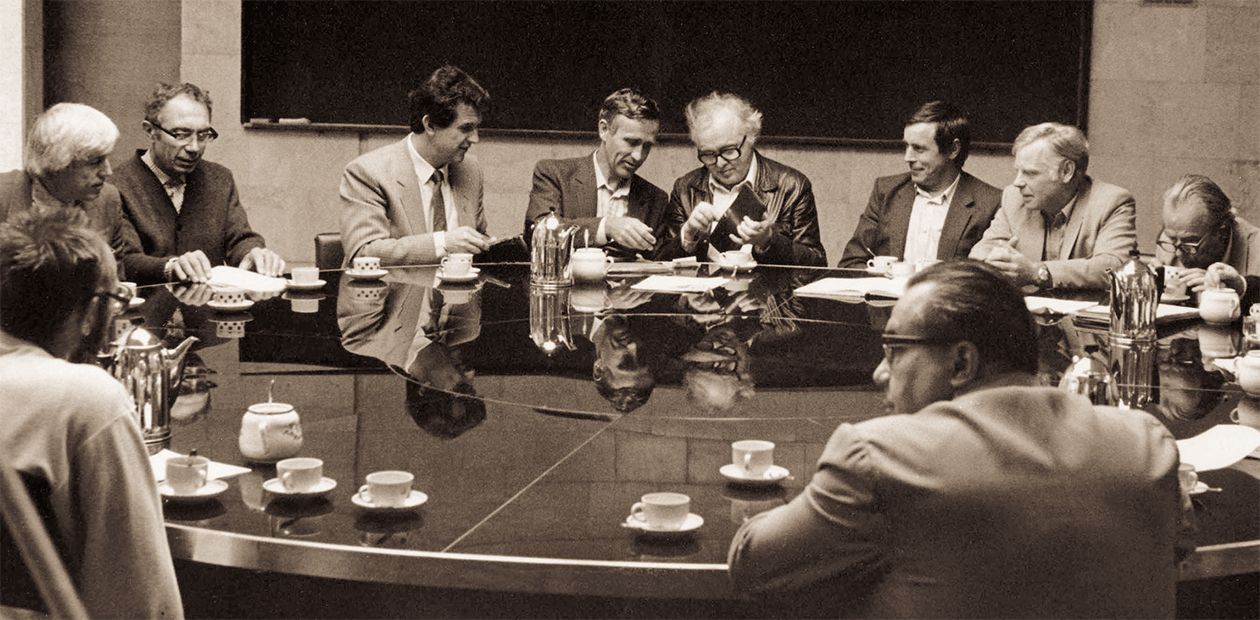

We chose a different strategy, according to which remuneration depends on how good and efficient the researcher is, and not on how well his current project is financed. The contribution of each researcher is assessed by the Academic Council, whose meetings are held around our Round Table. Importantly, this assessment is not a formal procedure performed by voting, but is achieved through discussion. Labs also have a say in remunerating their workers: they can regulate salaries using their own bonus funds. The bonus fund of each lab is made up of a certain share of the money it has earned through contracts. Top executives review the situation with the distribution of funds and can revise it — the directors have much power and, accordingly, bear heavy responsibility.

At first, not everybody approved of this approach to financing, and it took some time to talk people into it. Life has proved that we are on the right track. In the end, virtually all the labs have had their ups and downs: sometimes their contracts brought them good money and sometimes nothing at all. The salaries, however, have varied only within of 10 %. Therefore, in the last six-seven years no more talking has been necessary: everybody have made their conclusions from their own experience.

— What are you personally more interested in: solving professional problems or problems of the internal and external policy of your Institute?

— Professional problems, of course, because they are the ultimate goal, and everything else is a means of reaching it. No doubt, dealing with some organizational, financial and management issues can also be exciting, and solving this kind of problems can bring you satisfaction, but in an indirect way. The most important thing for the Institute is to keep in the vanguard of physics, even if we manage to do it only in some narrow fields, despite our rich research potential. If our funds were not so limited, we could, instead of participating in international projects on a commercial basis, afford to invest money in our work here, in quicker and better construction of some experimental equipment for ourselves.

Recently INP has faced a new task common to many research institutes older than 40—50 years old, which is to find a way, natural and easy both for the institute and for its research workers, of replacing the institute’s top executives, i. e. to ensure “reproduction.” A most challenging task.

Replacement of the older generation is a very sensitive issue. At INP we arranged it in such a way that the financial situation of the people who used to hold key positions (heads of laboratories, directors, etc) does not get worse after they leave their posts. Their salaries continue to increase in the same way as the salaries of other employees. They do not perform administrative functions any longer but continue to do research and participate in INP’s management, to the extent that their health allows them to do this. This practice has helped the older generation to preserve good shape and has given them many years of fruitful work.

— Did you have somebody in your life who was a model for you, somebody whose example you wanted to follow? Maybe your teacher of physics at school or at university?

— As for teachers, the teaching of physics at our school was very poor indeed. Nevertheless, I got interested in physics, including nuclear physics, very early, beginning with the 7th grade (I was 14 years old). In fact, I was a quiet top student. Our grade was not very ordinary: 12 people out of 28 had excellent grades in every subject, though it was not an elite school at all. Two years before I left school (which happened in 1953; it was a time, I can tell you…) I had a conflict with my physics teacher. “What are you smiling at, Skrinsky?” he would ask. I don’t remember why I was smiling, but the teacher didn’t like it.

I didn’t get on too well with the teacher of Russian literature either. We were reading the article Party Organization and Party Literature by Lenin, and I tried to prove to the teacher and to the class that Lenin had meant political literature and not belles-lettres, “It’s written right here, crystal clear!” It was silly of me, of course; and the teacher responded by asking me to leave the classroom or by making me stand in front of the principal’s office as a punishment.

In 1957 I came to Budker’s lab for my pre-graduation practice. At that time, it was known that the lab would grow into a research institute, but no formal decision had yet been made. It was signed only in 1958.

I looked at my life before 1957 as the preparation for this new, real life. At University I went in for sport: track and field athletics, hiking, etc; but in my fifth year I lost touch with the University and focused entirely on this lab, our future institute.

When I said I was going to have a holiday, the head of the lab made a fuss: how could I take a holiday when there was this and that to do! So, much as I wanted to go hiking around Lake Baikal, I didn’t make it. From the moment I joined the lab as an undergraduate, I became an equal research worker, not somebody at the boss’s beck and call. This is how my real life began.

The first few years were very hard, psychologically, because every year we set a task for ourselves and failed to do it. And not just failed to do it that year, but also the following year and the year after that too. The tasks we set were most difficult and arduous, nobody in the world could do the job, and that’s why there was no one we could turn to for help.

There were lots of other questions we wanted to ask Alexander Skrinsky, the man whose life has been so tightly interwoven with the life of most famous research institutes of the country, that it makes you remember Soviet slogans on the unity of “the power and people”. By the way, INP’s researchers gave Alexander Skrinsky a gift — a real royal throne made of metal and precious woods for his previous anniversary. The throne was to be put next to the famous Round Table around which the Institute’s Academic Councils are held. However, the hero of the day refused to do this politely but firmly, in order not to break the long-lasting tradition of democracy started by INP’s first Director and Skrinsky’s teacher Gersh I. Budker. And the throne was just put aside…

The matter was solved a few years later, in Novosibirsk. We were the first in the world (simultaneously with the Stanford Laboratory, USA) to substantiate that it was possible to create an accelerator with colliding beams. A bird in the bush finally became a bird in the hand. To tell you the truth, we had no idea whether we would ever succeed: lots of labs all over the world had been working on it with no result.

A senior colleague and friend of mine, who had decided to stay in Moscow, said, “Are you going to Novosibirsk? How stupid! Take my word, you will fail.” He said that at first G. I. Budker would try to make colliding beams and fail, then “jump” to military orders, and then everything would fall apart. He was sure I would eventually come back to Moscow and even promised to have me back because I was “up to standard.” At that time he was a Candidate of Sciences, but he got his Doctor’s Degree many years after I was elected academician. It happened so that life itself was the impartial judge of our decisions.

The editorial board would like to thank A. M. Kudriavtsev, Candidate of science in Physics and Mathematics, INP’s Secretary for Science, who helped us to prepare this article; A. I. Shliakhov and I. V. Onuchina, Editorial and Publishing Board, for photos from INP’s archive

* Head of the USSR Government from 1964 to 1980