A Garden Born by Inspiration

There are quite a few iconic places in Akademgorodok; one of them is the Central Siberian Botanical Garden. Rain or shine, the locals walk its trails. Couples and jolly crowds of university students, bikers and joggers, moms with bubbly toddlers, elderly people strolling leisurely… On weekends, people come to the Botanical Garden from all around Novosibirsk and its satellite towns, and visitors to our city are always told to check this place out.

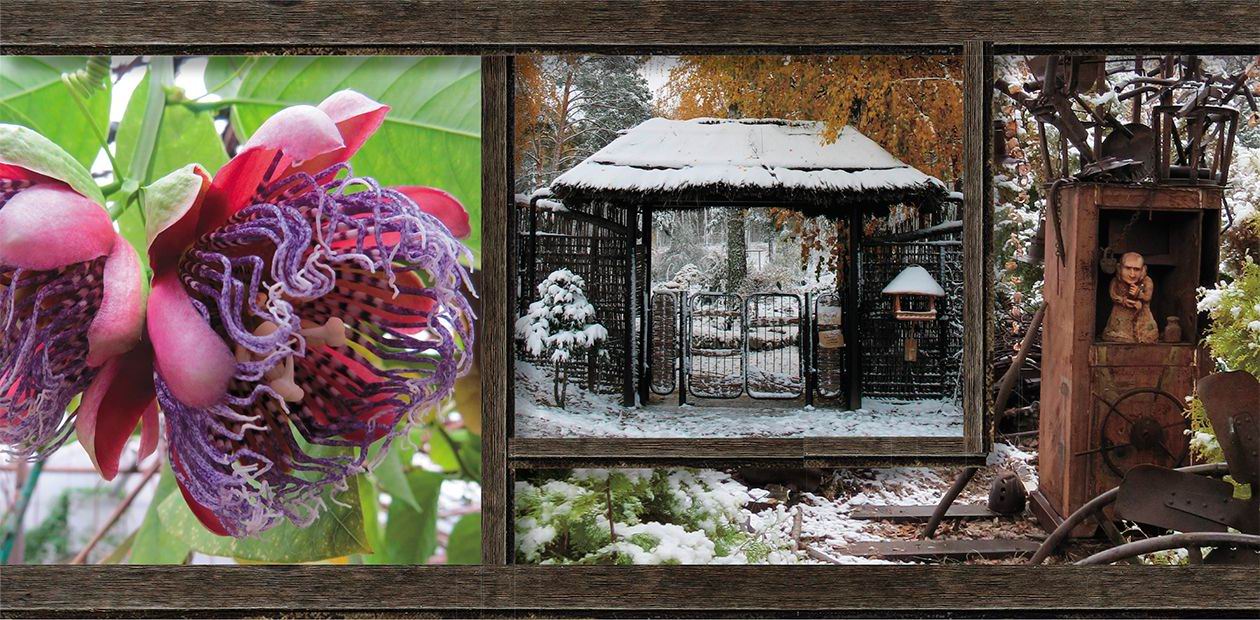

The joy of picnicking on green lawns or feeding ducks, taking pictures in the gold of fall or walking in the snow and listening to the winter silence is open to everyone. But there are secret nooks and sanctuaries in the Botanical Garden that only a tour guide can show…

Some fundamental processes and phenomena are sometimes hard to explain to lay people. Yet there are things that seem simple and obvious to absolutely everyone: for instance, edible, medicinal and ornamental plants. This seeming banality and the fact that botany is one of the oldest life sciences explains the often condescending attitude to field botany nowadays.

You don’t have to travel far to see this for yourself: in the Novosibirsk Scientific Center, the Botanical Garden is thought of not as a leading research institution but rather as a curiosity, an outdated guild with flower pots and vegetable gardens. But is this fair – or, more importantly, true?

Early sprouts

Botanical gardens are created primarily for the purpose of conservation of the global plant diversity. It allows the recovery of species that, for one reason or another, become extinct in the wild. They are a sort of zoos for plants.It is common knowledge that as humans reclaim new land, they interfere with the nature and disrupt the intimate connections that have been forming for millions of years. Quite often, unique locations are destroyed together with their plants, which we will never even know about. We will never get a chance to register the new organism, study its properties and the potential for its use by humans – it goes extinct, unknown and unnoticed. This happens both on the global scale and within a particular botanical garden

The Central Siberian Botanical Garden of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences is a complex structure: a real botanical garden and a full-scale research institution. It hosts a range of specialists sharing a common research object – the exceptionally diverse and complex world of plants and fungi. Nowadays we can study it on various levels: from major landscape formations on the global scale to individual populations, from whole organisms to cells and cellular structures. To solve specific botanical problems, researchers study their objects directly in the field and in experimental plots with plant collections. These are the “fenced gardens” that puzzle pedestrian visitors of the Botanical Garden.

The history of botanical gardens illustrates vividly the implementation of the concept of “living collections.” It all began with “apothecary gardens.” When scientific classification of the plant world began to emerge, it led to the creation of the Systematicum, or collections of related plants, both beautiful and informative. This is how the first botanical gardens in Europe in the XV – XVI centuries began: they had the mandatory collection of medicinal plants and the Systematicum, which served as a living collection and had educational value.

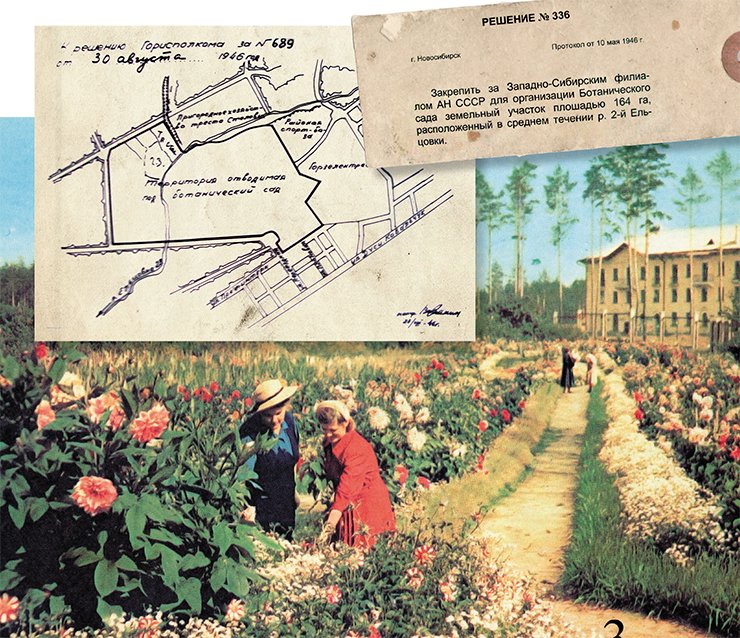

In our country, the history of botanical gardens began three and a half centuries ago, also from “apothecary gardens.” Our Garden is relatively young – it is only 70 years old. It was founded in 1946 together with the creation of the West-Siberian Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences. In the difficult post-war period, the country was recovering slowly; there was a deficit of specialists and resources. As soon as the Garden got its first hectares of land, instead of display collections it was allocated for practical tasks. Only later the first collections of rare and amazing plants appeared, bearing an inherent value and serving to popularize the biological science.

Initially, the Botanical Garden as an independent organization had few staff workers; the newly created experimental laboratories focused on the issues of introduction and acclimatization. First, collections of berry shrubs, fruit trees and vegetables appeared, followed by ornamental plants. A year later, the dendrarium was founded. This was the time when the first dissertation theses were defended, based on the results obtained in the experimental plots.

After 10 years, the living collection of the Botanical Garden included 4.2 thousand species, forms and varieties of plants. In 1955, the Botanical Garden was excluded from the Biological Institute of the Siberian Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences and made into an independent structural unit. When the Siberian Branch of the AS USSR was created, the collections of the Botanical Gardens were gradually transferred to the newly founded Akademgorodok.

The transition was not without losses; some specimens were left in place, much to the delight of the locals – becoming an eternal headache for the city’s officials. The area commonly known as the “Botanical Garden” near the Novosibirsk Zoo testifies to this statement. The name of the nearest bus stop reminds that sixty years ago there was indeed a botanical garden there. Naturally, all collections of herbaceous plants have vanished, and few employees of the Botanical Garden nowadays can name those first plants. But the various trees planted by the first generation of the CSBG researchers are still there.

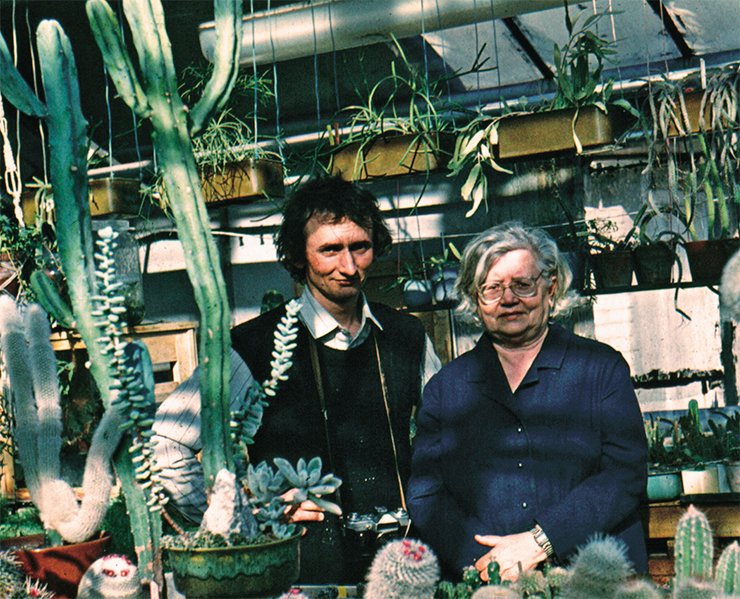

The 1970s—1980s were the true high noon of the living displays of the Central Siberian Botanical Garden.

The high noon

The transfer of the Botanical Garden to its current location, Akademgorodok ended in 1964. The institute received over a thousand hectares – a giant territory even by the standards of that time, unimaginable nowadays, just steps from the residential areas of Akademgorodok. The vastness of the territory has been a subject of unabated envy of our colleagues from other Russian botanical gardens – and real estate developers cannot get it out of their minds, either…

In many ways, such collections are akin to a living organism: they are born, they develop – and they die. Today, there are still a few old school professionals working in our Garden. When they leave, their collections often follow. Collections of art or rare coins are disseminated throughout the world after their owner’s death, but they can be restored someday; collections of plants are deprived of such a possibility. The unwritten rules state that a collection “orbits” a single person, the charismatic leader interested in a specific group of plants. If there are successors, the collection will live and grow even after the leader is gone. If not, the plants will perish

From the very start, the land was managed smartly. First, the general layout of all buildings and landscaping was designed. The institute was busy working on existing subjects and tackling brand new directions, and the construction was going fast. The influx of young specialists was unprecedented: at no other time in history there were so many young researchers working on the creation of collections hand in hand with seasoned experts.

А bit earlier, in 1958, the Botanical Garden was merged with the local Experimental Forestry Station (Russian: ЛОС – лесозащитная опытная станция). This doubled the duties of our researchers: in addition to theoretical foundation of acclimatization, they had to solve the urgent task of radical improvement of the forests and parklands of the Novosibirsk Scientific Ceneter. This is a good time to remind the reader that the current green image that Akademgorodok takes pride in has been created by the experts of the Botanical Garden.

No other town in Siberia can boast of the same diversity of tree and shrub species and forms, well-designed landscaping groups and green areas as Akademgorodok. It is the result of hard work and enthusiasm of many people, who put their souls into the creation of the collection of trees, investigating the possibilities of their acclimatization in South Siberia and literally implementing this knowledge into the living and working space of all citizens and guests of Akademgorodok.

By 1975, the construction of the garden and new displays on the new territory was mostly complete.

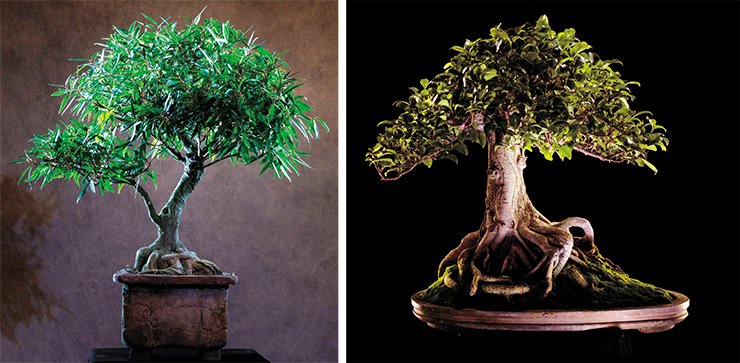

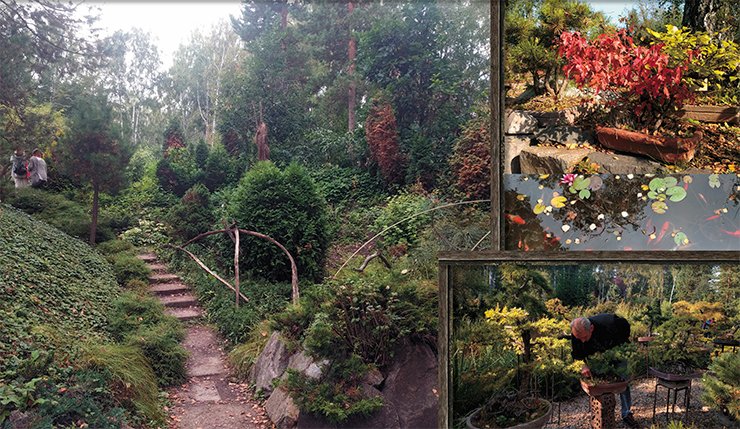

The Bonsai Park of the CSBG SB RAS is our own attempt to create a similarly enchanted space. The concept appeared back in the late 1990s. In the beginning, we just planned to create and display a collection of temperate-climate arboreal plants grown in containers – the Japanese word bonsai literally means “grown in a tray.” But the idea grew, resulting in a plot with about three thousand taxa from East Asia, Far East, European Russsia, Western Europe and North America, distributed according to their geographical origin, including trees, shrubs and herbs. There are bonsai, too, – over three hundred and fifty of them.”

The area was divided into four parts. The largest part was left in primeval state and has stayed like that until the present day. However, it took incredible effort of several generations: Akademgorodok was growing, and beautiful old forest next to residential areas has always been a tasty morsel for the developer industry. In terms of research, this territory was virtually abandoned until the last five years: before that, priorities were different and there were no available resources to study the forests of the Botanical Garden thoroughly and systematically – i. e. create checklists for all groups of the plant kingdom, describe and classify the vegetation types, etc. However, this extensive work has finally been done and published – creating a starting point for monitoring programs.

Another big part of the area has been allocated for the displays of arboreal plants, with a network of trails. The Upper and Lower Dendrariums occupied huge areas; the area around the main and experimental buildings of the Botanical Garden was turned into parterre and park zones. The rest of the area hosted experimental collections, nurseries, seed plots and fields of the experimental research farm of the CSBG.

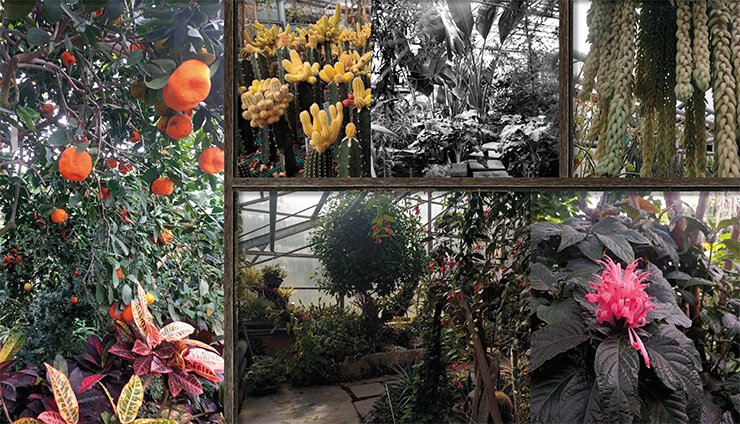

By the end of the 1980s, the living open ground collections of the Botanical Garden occupied about 300 hectares of land. In addition, there were 8500 square meters of protected ground collections, occupying several mostly plastic film greenhouses.

At that period, most of the open ground displays were true gems of the Botanical Garden collections. They were planned as large-scale projects from the start, with annual additions from the well-organized exchange fund (“the seed cabinet”) and with plants brought from numerous and extensive expeditions to different natural zones of the former USSR. The care for the collection, such as watering and seasonal works, the work of the service yard with gardening equipment and motorized vehicles and, more importantly, the management of human resources was so well-organized that today’s generation of botanists simply refuses to believe that it is even possible.

For instance, should a collection be divided into parts? A part with plants that will survive being on display and a part containing rare and unique specimens – that only an expert can truly appreciate? Quite often, this is the case. But if all specimens are stored in the same collection, on the same plot, everything must be thoroughly monitored – both what the visitors and the caretakers do.

Force majeure events happen – and plant collectors are not immune. Insects, epiphytotics, power and heating outages, light-fingered visitors – or just guests seduced by rare specimens – are the true plague of any protected-ground collection. Everything must be taken into account. For instance, there is a unique specimen of the common dandelion growing in the Bonsai Park – and every passer-by tries to pluck it out, because people think dandelions are weeds. I found it at the other end of the world – in the Andes! How did it get there? Maybe it was the great German scientist Alexander Humboldt who brought dandelion seeds on the soles of his shoes while studying the flora of South America. And here it is – a spectacular plant, with leaves almost a meter long – doing well in Siberia. It has been plucked on numerous occasions, but half-heartedly: the roots survived and sprouted new growth. It is alive and well, thank God.”

There were amazing collections of medicinal plants and wild flora of Siberia, which also served as the Systematicum, and the flora of the Far East; collections of fodder and ornamental plants – gladioluses, peonies, roses, chrysanthemiums, lawn grasses, selected forms of pasque flowers and dendranthemiums, rare and redlisted plants, fruit trees and shrubs, vegetables… everything was blooming – a delightful sight for the visitors and a fruitful bough for the researchers. This yielded a rich harvest of publications and results of theoretical and applied research that can be found in reports of that time and in the 1981 “Guide to the Botanical Garden.”

What survived and what has been added? In the post-Perestroika turmoil of the 1990s, when the influx of new people into science skipped a whole generation, it was no longer possible to persuade the state officials that botany was no less important than physics or molecular biology, and supporting the collections on this scale became an unaffordable luxury.

To save the remaining herbaceous plants, the experimental collections had to be transferred directly to the main building of the Institute to provide the necessary care. The collections were dying in agony. People were leaving, funding was decimated, and enthusiasm was trickling down the drain…

The Systematicum in its initial form became a thing of the past; patches with ornamental and edible plants shrunk and withered; the nurseries dying and the collections of fodder plants lost. The collection of medicinal plants is still alive, but in the future, the institute administration is planning to end the studies of pharmacologically important species, which means an imminent death of the collection. The parks and dendrariums are failing to cope with the increasing recreational stress.

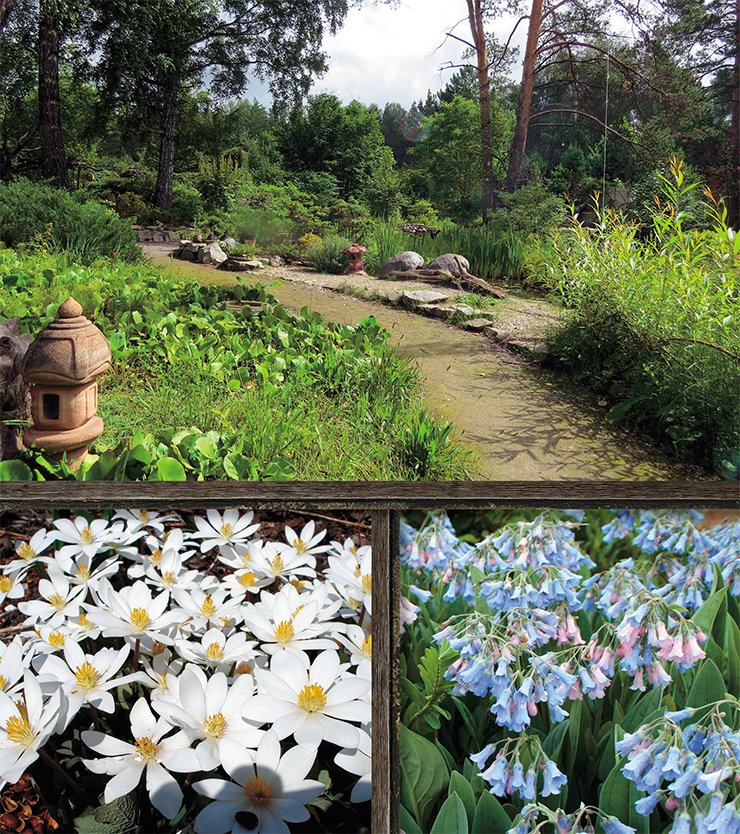

Things are not that bad however. The walking trails in front of the main building are thriving, forming an amazing blooming belt. The Upper and Lower Dendrariums are well-groomed, and the Syringarium is developing well, with a collection of varietal lilacs. The Endless Blooming Garden and the Rock Garden are doing well, too; the latter was the first landscaped garden in the Garden with wild and ornamental plants, created back in the 1970s. In 2017, a new patch appeared, dedicated to topiaries, i. e. trees and shrubs with crowns clipped into ornamental shapes.

The greenhouses are changing, too. The protected ground collection of plants in the CSBG includes 7500 different taxa. The ten greenhouse exhibitions include only a part of the collection: it is in the process of moving, and soon, it will be possible to exhibit more specimens. For instance, the cactus exhibition used to be limited to 20 species, but after the opening of the succulent exhibition, there are now 350 species! The same is true for orchids and ferns – nowadays, we “stock” about 800 species, which have never been shown to the public before; now we have the possibility to do that.

The Bonsai Park is developing as well; it essentially became the New Systematicum, but on a larger scale. At the same time, it serves as a vivid example of the way to turn a boring systematical collection garden into a majestic and enchanted landscaped park.

Research in experimental botany continues as well. The Edible Plants and Rare and Endangered Plants turned out to be the most tenacious and long-living collections of the CSBG. It was made possible by the continuity of tradition and charisma of our experts, which we cannot but keep mentioning. The Botanical Garden owes its remaining assets to the amazing devotion and motivation of the people who conceived, created and cherished their living collections – and managed to pass them into the caring hands of their successors.

The Central Siberian Botanical Garden has a lot to show to its visitors – for the time being…

References

Korolyuk E. A. On the occasion of the Herbarium Anniversary: a FAQ for poets and physicists. SCIENCE First Hand. 2014. V. 56. N. 2. P. 64—87 [In Russian].

Plant diversity of the Central Siberian Botanical Garden of SB RAS / Koropachinskiy I. Yu., Banayev E. V. (eds). Novosibirsk: “Geo” Academic Publishing, 2014, 492 p. [In Russian].

Sedelnikov V. P., Korolyuk A. Yu., Lashchinskiy N. N. A Lost Archipelago: The Altai Krai through the Eyes of a Botanist // SCIENCE First Hand. 2010. V. 25. N. 1. P. 30–45.

The Central Siberian Botanical Garden: A Guide. Novosibirsk: Nauka, Siberian Division, 1981 [In Russian].

Photographs by the authors and from the Botanical Museum of Siberia Archive, Novosibirsk