Nullius in Verba, or is Yoga Useful

and on the Periodic System of the Elements, Quackery and the Evading Research Object

In recent years, the concept of “quackery” has blended into our active vocabulary. When we read about charged water, torsion fields, the influence of moon light on train rails (we’re not joking here), cloning humans or, say, living longer using meditation, how do we know if it’s the truth, a fake, or a mistake made in earnest? Assessing the authenticity of information can be a challenge unless you are an expert in the specific field; however, anyone who has basic knowledge of the subject can assess the tools that the scientists used and the proof they collected, and use it to draw simple logical conclusions

Science is a powerful thing. But what does science mean? As a rule, we use the concept of science intuitively, mixing it into our speech whenever it feels handy. However, each word has a dictionary definition. Let’s look it up in the dictionary.

The definitions of science change from one dictionary to another, but they agree in one thing: science is a type of human activity. The goal of science is in acquisition and systematization of objective knowledge of reality. To achieve this goal scientific workers, or scientists, use a system of tools, which has been defined at the dawn of modern science by the Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge, founded back in 1660.

These tools have not changed much, which means they have stood the trial of time. The slogan of the Royal Society, Nullius in verba (Latin «on the word of no one») states that any theory must be based on repeated observations, experiments or mathematical calculations, but not on words of authorities. Hypotheses are proposed to explain observed facts and are to be confirmed experimentally; next, a multitude of hypotheses constituting a theory serves as the foundation for a cause-effect model of the studied object, which allows predicting its behavior in various conditions.

«What if I’d been thinking about it for twenty-five years…»

Note that the definition of science as a type of human activity does not imply any limitations on the object of study, however, it does prescribe a certain code of behavior for research workers. In particular, researchers must use scientific tools – but not religious tools, for instance. Even though Dmitry Mendeleev saw his famous periodic table in his sleep, his landmark paper, “On the Correlation between the Properties of the Elements and Their Atomic Weights”, published in 1869 in the Journal of the Russian Chemical Society, is not a narration of this dream; it is a systematic description of a new consistency.

As we know, Mendeleev has shown that as the atomic mass of chemical elements increases, their properties change periodically rather than monotonously. To prove his theory, Mendeleev provided a number of observations. For instance, potassium is similar to sodium by its chemical properties, even though potassium is heavier; fluoride resembles chlorine, and gold belongs to the same group of elements as silver and copper.

Moreover, Mendeleev bravely faced the potential storm of criticism, using his theory to pinpoint errors in atomic masses and descriptions of some elements. He went even further: in his table, he left blank cells for elements, which were yet to be discovered. Mendeleev’s amendments turned out to be correct. The predicted elements were discovered rather quickly. These predictions became a powerful proof of his periodic theory. When asked about his prophetic dream, Mendeleev replied: “I may have been thinking about it for twenty five years, and here you are, assuming: he just sat and wrote it down, a dime a line, a dime a line, done!”

Mendeleev was not alone in tackling the systematics of the chemical elements. A bit earlier, D. A. R. Newlands, a well-known English chemist and musician, proposed his own system. His model was called “the law of octaves” and even superficially resembled the periodic system, however, it lacked a predictive value. Newlands strived to explain the periodic properties by a mystical musical harmony, but failed. Which did not stop him from excelling in another field, just as important as science – the sugar refining business.

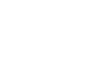

Ghosts as a scientific object

Imagine a successful Mendeleev studying the properties of something different – not chemical elements, but, say, ghosts. That may be hard to fancy: we know for sure that there are no ghosts. However, a true worker of science must be indifferent to the choice of the object of study. The more difficult the task, the more enthusiasm it should spark.

The proof of the “absence” of something is an extremely difficult task. The lack of a ghost in a room, just as the lack of black swans in nature, will remain a valid fact until the moment the ghost appears, or until the researcher reaches Australia, where all swans are black. The observation that “there are no ghosts” cannot be proven by any finite number of observations of the room. The scientist will be forever exposed to criticism from enthusiastic spiritists pointing at the “insufficiency” of scientific method as their main argument.

In 1875, ten years after his groundbreaking discovery, Mendeleev, a true scientist and an ace of the scientific method, oblivious to the risk of being branded a nonsense-mongering quack, rolled up his sleeves and created the Commission on the Study of Mediumist Phenomena at the Russian Physico-Chemical Society in response to the blooming Spiritism in the Russian Empire of the day.

The Commission invited well-known foreign mediumists to Russia – the brothers Petti and the infamous madame Claire. Both the spiritism appreciators and members of the Commission were present at their sessions; Mendeleev personally devised a manometric table, which measured the pressure applied to it. Mediums sitting at this table suddenly noticed that the “spirits” refused to communicate with humans: the precise pressure detection provided accurate proof of the mediums’ dexterous hands. At the end of its work, the Commission issued a conclusion: “Spiritist phenomena ocur from involuntary movements or intentional deceit, and the teaching of Spiritism is a superstition…”

However, the conclusion of the Mediumist Commission is secondary in relevance; rather, we are interested in the fact that a well-respected scientist, the father of modern chemistry, did not consider Spiritism a simple hoax not worth examining, even though it was beyond his own scientific scope. On the opposite, the scientist took the problem of Spiritism as a challenge and tackled it with a correct application of scientific tools instead of simply brushing ghosts off the table of reality.

No ideology involved!

Once scientists add the scientific method to their arsenal, they cannot use it selectively. If instead of the mediums’ cheating Mendeleev’s table had recorded true oscillations of the global ether, the scientist would have to acknowledge the existence of ghosts, just as he had to accept the existence of the yet undiscovered chemical elements earlier. However, that did not happen. Or rather, that did not happen that time. Remember the black swans – they did not exist in nature exactly until the moment researchers reached Australia.

Philosophers of science worked out a very important criterion, which allows telling a true scientist from a quack. The quack cannot formulate the conditions which would force him to deny his own theory. A scientist can. “What should happen for you to abandon your hypothesis?” is the very question that the famous philosopher and sociologist Karl Popper asked Marxists. He did not get an answer and applied the falsification criterion, declaring Marxism a quack theory.

Popper’s falsification criterion is not ideologically tinted in any way. Had the Marxists given in just a bit and described the horrifying society of victorious capitalism – as theoretically possible, Popper would have given up and accepted the theory of Marx as scientific. This is exactly why Lenin, in his famous statement “The teaching of Marx is omnipotent, because it is correct” essentially shot himself in the foot (Lenin, 1913).

Modern scientists en masse fail to reach the same heights as Mendeleev – for a number of reasons, which are beyond the scope of this discussion; primarily, this is due to the lack of classical education, which does much more than just expand the horizons; it forcefully prescribes the scientist to boldly rely on the power of the scientific method, without limiting oneself to “tried” and “safe” research objects in terms of scientific reputation.

For a real scientist, a reasonable argument for abandoning the study of, say, the effect of the notorious homeopathy would be not the “quackery” of this treatment method but the triteness of the homeopathic problem studied inside out in a multitude of published research works. However, even this argument cannot hold forever.

For instance, the study of nonlinear relationships between a dose of a substance and its effect and the phenomenon of hormesis (the stimulating action of low doses of stressors) are not that distant from homeopathy, yet these topics are quite fresh. In contrast to these studies, homeopathy looks like an innocently naïve and a wholeheartedly ineffective attempt to expand a handful of “successful” healings into a universal theory, thoroughly outdated yet alive in the minds of its appreciators, akin to the medieval treatment of leukemia with arsenic preparations, which, by the way, have been reintroduced into the pharmacopeia as differentiating agents to control certain types of acute leucoses.

Yoga against aging – why not?

In the past few years, real “no fear, no blame” scientists carried out a series of interesting research projects on the connection between the scientifically proven phenomenon of cell aging and physiological results of esoteric practices, such as yoga.

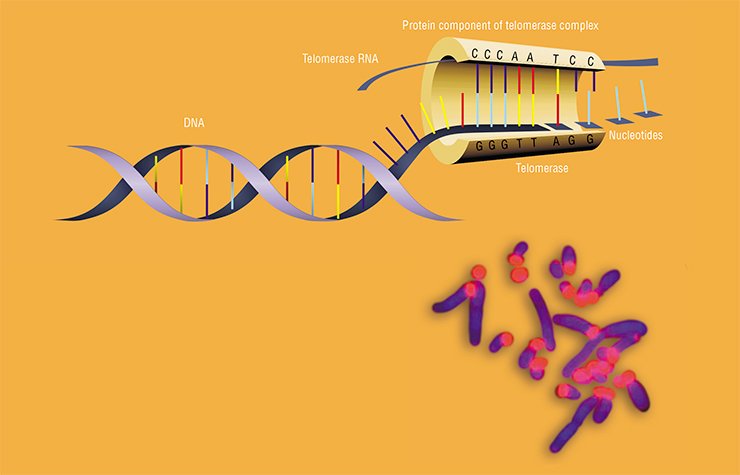

Cell aging is accompanied by a gradual increase of the oxidative stress and the shortening of telomeres, the terminal regions of chromosomes, which function as “safety lids” at the ends of these very long molecules. Both the oxidative stress and telomere length can be measured, yielding an objective estimate of the intensity of aging of an individual organism and of its biological age.

According to one of the theories, aging happens due to telomere shortening with age due to their incomplete replication during the doubling of the DNA strand. Nowadays we know that the length of telomeres and lifespan are not directly connected, but another factor comes into play here – the telomerase enzyme, which can lengthen the telomere regions of the DNA which shorten spontaneously during cell division. Overall, we can think of the telomere-telomerase balance as one of the quality markers of cell aging; in humans, shorter telomeres are likely to be connected with unfavorable processes in the organism. However, exceedingly long telomeres may signal about a high risk of oncological disease.

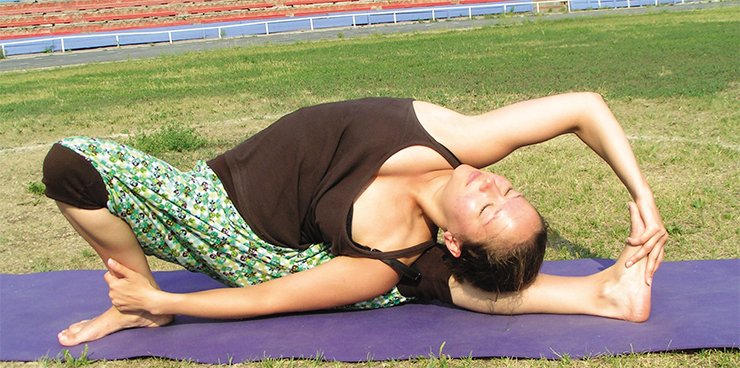

Yoga is a religious and philosophical teaching encompassing a system of techniques and exercises performed to control one’s psychological and physiological processes to achieve a special spiritual state. One of the techniques, the so-called meditation, is used to achieve the state of inner quiet and concentration. Nowadays, however, many people go to “yoga classes” as a set of physical exercises, and “meditative state” is just a way to spend a couple of hours oblivious to everyday problems. No religion or philosophy whatsoever.

But does a complex of physical and breathing exercises and meditative states really improve health and prevent cell aging? Well, why not?

A 2012 review paper summed up the results of 40 years of experiments aimed at understanding whether yoga can help with certain pathologies (Büssing et al., 2012). Researchers focused on psychiatric, cardiovascular and respiratory conditions. A bird’s eye view shows that the conclusions of many of these works often contradict each other. Some articles report positive effects of yoga expressed in the decline of stress levels and of manifestations of psychiatric disorders. In other works, authors fail to provide sufficient proof of these hypotheses. Performing a meta-analysis to be able to draw valid conclusions is hampered by the flawed design of these studies; this is especially true for earlier works. Moreover, the works as such are not numerous, and access to research conducted in India is limited. However, the authors stress the potential of this research direction. Yet everything must be done according to the current scientific standards.

When mitochondria do not «leak»

Research published in 2015 has demonstrated that yoga practitioners with at least two years of experience have a higher total antioxidant status and longer telomeres comparing to people living regular lives (Krishna et al., 2015). The overall conclusion was that yoga slows down cell aging; however, the mechanism of this phenomenon remained unknown.

A 2017 overview states more directly that various meditation practices have one thing in common: they all lead to the decrease of activity of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway, which is the main conductor of systemic inflammation (Buric et al., 2017). The authors conclude that meditation indeed helps to damp down the acuteness of symptoms of inflammatory diseases.

In another fresh article, researchers scrutinized the effect of practicing yoga on cell aging in about one hundred healthy people (Tolahunase et al., 2017). Training took place five days a week and included both physical and breathing exercises and regular meditation. Throughout the period of study, researchers measured changes in the levels of cell aging biomarkers, such as 8-hydroxy 2’-desoxyguanosine (8-OH2dG) – a marker of oxidative damage of DNA, as well as concentrations of active forms of oxygen, the total antioxidant activity, levels of cortisol, the stress hormone, and some other proteins, length of telomeres and telomerase activity.

They found that after three months of practice the subjects had decreased values of “bad” and increased levels of “good” parameters. The stability of the subjects’ genomes and the telomere-telomerase system increased the balance of pro- and antioxidative systems activity and the neuroplasticity improved. However, researchers still refrain from suggesting a possible mechanism of the influence of yoga and limit themselves to abstract speculations on stress in the modern lifestyle and the ability of yoga to reduce that stress, as well as on the role of “regulated mind-body communications” in suppressing subclinical inflammation symptoms.

They found that after three months of practice the subjects had decreased values of “bad” and increased levels of “good” parameters. The stability of the subjects’ genomes and the telomere-telomerase system increased the balance of pro- and antioxidative systems activity and the neuroplasticity improved. However, researchers still refrain from suggesting a possible mechanism of the influence of yoga and limit themselves to abstract speculations on stress in the modern lifestyle and the ability of yoga to reduce that stress, as well as on the role of “regulated mind-body communications” in suppressing subclinical inflammation symptoms.

The reasoning is more or less the same in other recent works: there is likely an effect, but what causes that effect?

For a start, let us have a look at some well-known pathological connections. Indeed, oxidative stress can facilitate premature shortening of telomeres and cell aging – that is a proven fact. Active forms of oxygen facilitate the modification of nitrogenous bases, predominantly forming the potentially dangerous 8-oxoguanine – the predecessor of the mutation of the guanine nucleotide into thymine, i. e. a completely different “letter” of the genetic code. Sequences of the telomere DNA contain many guanine groups, which make telomeres an easy target for the deleterious action of active forms of oxygen.

It is possible that yoga does help against cell aging by lowering the levels of stress in humans, because the stress essentially is active oxygen? If our cells feel uncomfortable, their power plants – the mitochondria – begin “leaking,” producing dangerous oxidants, which cripple the cells from the inside. Say, your boss bawls out at you, you take it too close, begin to worry about getting fired and get upset. This upsets your brain cells, too, and damages them – and they get a bit older. If your boss yells at a yoga practitioner, he or she will literally blow it off and forget about the problem that has not even happened yet. The yoga practitioner’s brain cells will not get upset – and damaged.

This may sound a bit too antropomorphic, but the “upsetting” of cells is based on a well-understood mechanism. The worried state clearly affects the activity patterns of various structures and regions of the brain, with some cells getting “overexcited” and drawing over the resources, affecting the blood flow. Other cells get robbed of oxygen and become prone to self-damage and apoptosis – the cell death. And we know that nerve cells recover very poorly – if at all. Yoga practice supports the total balance of the blood supply to the brain, preventing imbalances in oxygen supply and, consequently, the risk of damage to individual brain cells (Minvaleev et al., 2014).

This may sound a bit too antropomorphic, but the “upsetting” of cells is based on a well-understood mechanism. The worried state clearly affects the activity patterns of various structures and regions of the brain, with some cells getting “overexcited” and drawing over the resources, affecting the blood flow. Other cells get robbed of oxygen and become prone to self-damage and apoptosis – the cell death. And we know that nerve cells recover very poorly – if at all. Yoga practice supports the total balance of the blood supply to the brain, preventing imbalances in oxygen supply and, consequently, the risk of damage to individual brain cells (Minvaleev et al., 2014).

Let us return to our muttons, i. e. ghosts. Suppose a scientist has been measuring the number of ghosts in a room using, say, a “LED Ghost Counter”. A hundred measurements consistently yield zeroes. The conclusion is obvious: there are no ghosts. Later, the observant and tireless scientists hears a story about yoga practicioners occasionally finding ghosts using something called “the third eye.”

They say the scientist spends his days in the basement with a solder, building a new contraption for capturing transcendental essences. No one knows neither the working principle of this device nor the results, because the scientist is all too responsible: he is aiming at the Nobel Prize and does not want to reveal “raw data.” As soon as his ingenious device becomes functional, and as soon as he accumulates the necessary data, our scientist, an equal of Dmitriy Ivanovich Mendeleev, will publish his groundbreaking research in Nature and Science – simultaneously. We will read it and rush to report it to you, our dear reader –everything you wanted to know about ghosts (but were afraid to ask)…

MEDITATON PRACTITIONER – ON THE MOLECULAR BIOLOGY OF MEDITATION My experience with yoga and meditation is firsthand – I have been practicing them for about 8 years. As a molecular biologist, I could not help taking a closer look at the biological mechanisms underlying their positive influence on the organism.

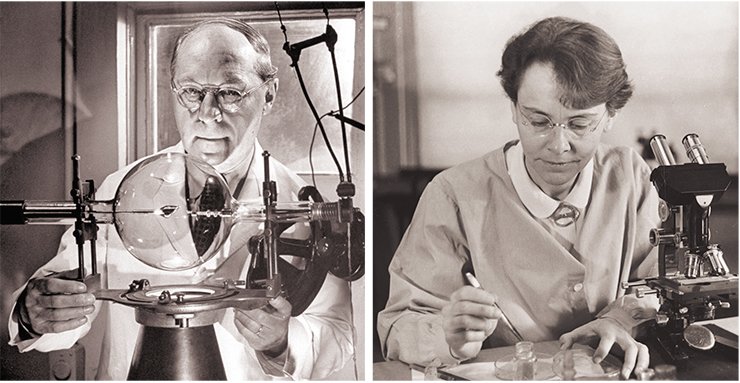

The phenomenon of cell aging is connected with the shortening of the telomeres, which protect the chromosomes from damage during cell division, and with the reduction of the activity of telomerase, an enzyme that restores the telomeres. Elizabeth Blackburn, an American cytogeneticist, was among the first researchers to study the connection between these processes and meditation. In 2009, Blackburn together with Jack Szostack and Carol Greider received the Nobel Prize for the discovery of telomerase and research in cell aging.

In one of her recent interviews, Blackburn noted that if she had been told that she would be studying the scientific aspect of meditation, she would not believe it. Today, a number of her works are devoted to the connection between the telomere parts of chromosomes and telomerase activity with stress – and with meditation. Blackburn believes that meditation has a positive effect on these chromosomal parameters, which serve as a kind of a marker of a person’s age and longevity. The more you meditate, the stronger the effect. Detailed results of this research are provided in a book she co-authored with Elissa Epel, The Telomere Effect: A Revolutionary Approach to Living Younger, Healthier, Longer; it was translated and published in Russian in 2017.

Other researchers came up with similar results. For instance, even a short (12-minute) session of kirtan kriya, a very efficient meditation technique, if practiced regularly, reduces manifestations of depression and anxiety and normalizes carbohydrate metabolism in senior patients (Khalsa, 2015). A remarkable detail: this practice increased their telomerase activity by 43 %! The technique does not require special physical skills; the Internet is full of video tutorials complete with music. There is one requisition, common for all meditative practices – regularity.

As for me, seven years ago, I discovered the dynamic meditation technique, and it turned my life around. It was invented by an Indian mystic and professor of the Jabalpur University, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, known as Osho. Unlike the previously described techniques, this one requires considerable physical efforts. There is very little available research on dynamic meditation. However, the available data suggest that practicing dynamic meditation leads to decreased levels of cortisol, the stress hormone, in the bloodstream. (Bansal et al., 2016). The technique effectively relieves anxiety (Iqbal et al., 2014). Psychotherapists recommend dynamic meditation to patients with depression; Dr. A. Fullham from Harvard University uses it as part of multiple sclerosis complex therapy (Gordon, 2009; Graham, 2010).

Naturally, many people are skeptical about such works, attributing the state of well-being after meditation and long-term preservation of this effect to simple rest. Such skeptics may be interested in the results of a study with two groups: women who had never meditated and experienced meditation practitioners. In the experiment, a half of the first group was “resting” and the other half was meditating for the first time in their lives (Epel et al., 2016). Levels of different biomarkers of all participants were measured, including the biomarkers of aging. It turned out that some values, such as reaction to stress and the state of the immune system, improved in all participants, however, only meditation practitioners – both new and experienced – managed to maintain low levels of stress for long periods.

In 2017, I prepared a lecture called “The molecular biology of meditation (how to meditate to lengthen your chromosomes),” which I presented at the “Science Story Night,” a scientific barhopping event that took place in October in Novosibirsk Akademgorodok. The title alone subjects us to quackery accusations. But meditation does help us cope with everyday stresses and challenges. For instance, in Canada, the Oncology Center of Calgary University has successfully implemented a program aimed at helping cancer patients, called Mindfulness-based stress reduction. It helps patients cope with fear and anxiety and focus on getting better to be able to deal with symptoms and serious side effects of cancer treatment more efficiently

References

Bansal A., Mittal A., Seth V. Osho Dynamic Meditation’s Effect on Serum Cortisol Level // J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016. V. 10. N. 11. CC05–CC08.

Blackburn E., Epel E. The Telomere Effect: A Revolutionary Approach to Living Younger, Healthier, Longer (Russian translation). Moscow: E, 2017. 384 p.

Buric I., Farias M., Jong J. et al. What Is the Molecular Signature of Mind-Body Interventions? A Systematic Review of Gene Expression Changes Induced by Meditation and Related Practices // Front. Immunol. 2017. V. 8., eCollection.

Büssing A. L., Michalsen A., Khalsa S. B. et al. Effects of yoga on mental and physical health: a short summary of reviews // Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012. Epub.

Epel E. S., Puterman E., Lin J. et al. Meditation and vacation effects have an impact on disease-associated molecular phenotypes // Transl. Psychiatry. 2016. V. 6. N. 8. e880.

Khalsa D. S. Stress, Meditation, and Alzheimer’s Disease Prevention: Where The Evidence Stands // J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015. V. 48. N. 1. P. 1—12.

Krishna B. H., Keerthi G. S., Kumar C. K. et al. Association of Leukocyte Telomere Length with Oxidative Stress in Yoga Practitioners // J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015. V. 9. N. 3. CC01–CC03.

Minvaleev R. S., Bogdanov A. R., Bogdanov R. R. et al. Hemodynamic observations of tumo yoga practitioners in a Himalayan environment // J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2014. V. 20. N. 4. P. 295—299.

Popper K. The Logic of Scientific Discovery (Russian translation). Moscow: Respublika, 2004. 447 p.

Tolahunase M., Sagar R., Dada R. Impact of Yoga and Meditation on Cellular Aging in Apparently Healthy Individuals: A Prospective, Open-Label Single-Arm Exploratory Study // Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017. Epub.