Children's Dolls Nerym Yakh. Toys As an Element of Traditional Culture

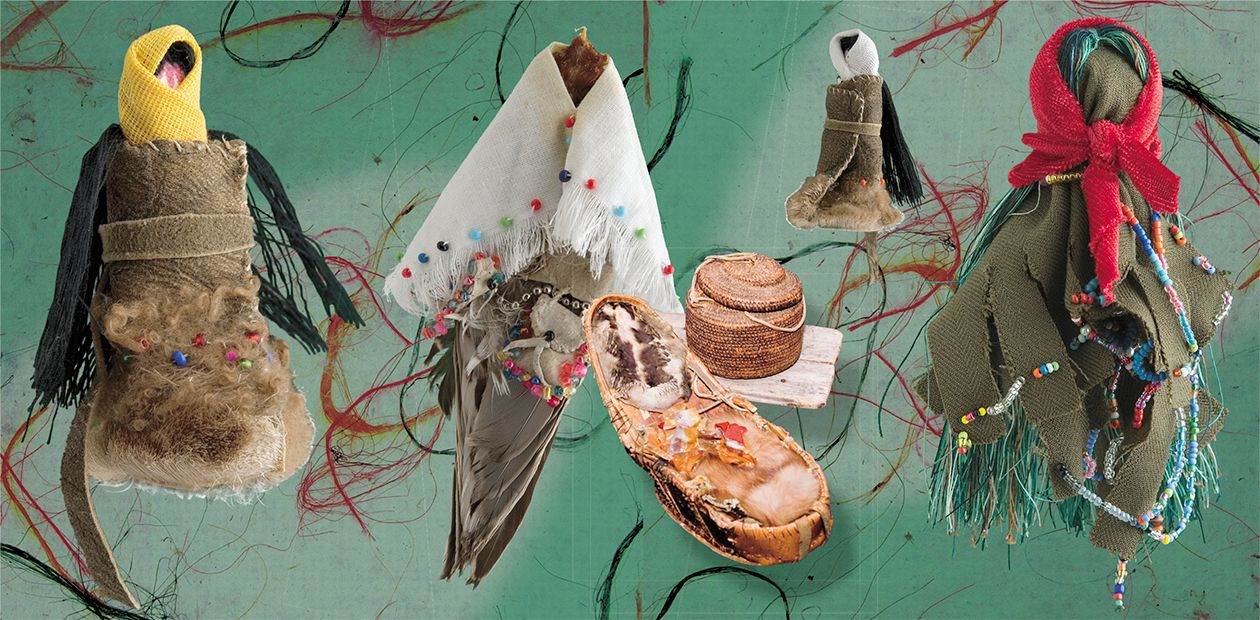

The ethnographic collection of the Nerym Yakh dolls ("Nerym Yakh" translates as "marsh people", a group of east Khanty inhabiting the marshes in the River Trom-Agan (a tributary of the Ob) catchment basin) of the Surgut Regional Museum of Local Lore was started at the beginning of this century. It came as a result of reconstruction of the process of making these dolls, which was performed with the assistance of Nerym Yakh craftswomen-consultants. Based on this collection, the book "Nerym Yakh Fairy-tales and Dolls" was published, and the Museum's Ethnic Puppet Theater was created. Today, both the collection and the theater have won recognition beyond Surgut: the project "Nerym Yakh Dolls and Fairy-tales" was presented at Eurasia 2006 competition among children's museum projects held in Moscow and St Petersburg and was awarded the Gold Medal in the category "In one's own way"

The primary goal of any museum is preservation and exposition of the most vivid samples of cultural heritage. This is especially true of regional local lore museums, which study traditional cultures and collect, investigate, preserve, and popularize their singular heritage.

The ethnographic collection of the Surgut Regional Museum of Local Lore does justice to the typical features of everyday life of the east Khanty inhabiting the catchment basins of the rivers Pim, Trom-Agan, Bolshoy and Maliy Yugan and their tributaries. The Museum’s interests mostly focus on the Khanty* communities living within the boundaries of the Surgut region.

Among the Surgut Khanty there is a geographically isolated group that lives in the Trom-Agan river (God’s river) catchment; they call themselves Torum Yaun Yakh (God’s river people). The Trom-Agan Khanty include three groups: Lapka Yakh (village people) living in settlements and villages, Lav Okh Ty Yakh (river people) living in camps along river banks, and Nerym Yakh** (marsh people), who live in marshes. The latter are the most difficult to access. Until mid-last century they were virtually isolated from both their neighbors and modern civilization, which has allowed them to keep intact many features of their ancient culture. Not surprisingly, it is this group that interests ethnographers most.

Until the beginning of this century the museum had practically no exhibits showing the culture of children’s games. This happened because by 1963, when the museum was set up, this part of the traditional Khanty culture had gone. The Khanty children spent most of their time in boarding houses, far from their homes, and the rules of the boarding houses did not allow the children to wear national clothes or play national games.

In 2004 the museum launched a project focusing on children’s games, toys, and their role in building the national social structure. Toys, undoubtedly, are an important element of any traditional culture. It is in toys, especially girls’ toys, that subtle nuances of material and spiritual national traditions are manifested. Toys not only reflect the diversity of sub-ethnic or geographically isolated communities of any nationality but make an important contribution to children’s skills development. On the other hand, toys reflect changes taking place in the world. For instance, the traditional Khanty toys depicting deer pulling sleds have been almost universally replaced with copies of snowmobiles—as they play, children more often imitate the sound of the motor and not the voices of the deer or squeaking of sledges sliding on the snow.

In order to resume the tradition of making and using toys, the Museum decided to reconstruct the way in which they were made. A few Nerym Yakh women of retirement age (consultants) were asked to reproduce the things that used to fill their doll bags. When making the toys, the craftswomen kept to the tradition. Studies into the data obtained have allowed us to describe certain elements of the play culture and create a collection of Nerym Yakh dolls.

The doll collection was created with the great assistance of Olga Shcherbakova, a retired nurse and Nerym Yakh descendent story teller. Olga not only helped make all the possible models of dolls but took an active part in preparing for publication the book Nerym Yakh Fairy Tales and Dolls and in the production of these fairy tales by the Museum’s Ethnic Puppet Theater.

Doll traditions

Khanty girls used to make their first dolls when they were about seven years old. By nine, they could make dolls’ clothes and accessories from plain materials: scraps of fabric and fur, threads, and beads left from their mothers’ needlework. The girls were allowed to play with dolls only in the daytime. There were age restrictions as well: by the age of ten or eleven games with dolls virtually stopped. Younger girls, from three to five years old, who could not yet sew on their own, made dolls for themselves out of a scarf or a small pillow. The scarf was folded in the shape of a baby nest to imitate a baby, and the pillow was put vertically and covered with a scarf to depict a baby lying in a Khanty cradle.

The dolls were no bigger than a child’s hand—a bigger doll was considered to resemble a child and therefore was unfit for playing. The smallest dolls were the size of a small finger—those were “babies” looking like swaddled babies in a cradle. No clothes were sewn for them because tiny clothes belonged to the obituary and burial practices.

The main distinguishing feature of Nerym Yakh dolls is their temporary nature. After the game was over, the doll had to be disassembled so that it did not become alive: the bits of fabric or grass from which the head and body (a doll mold) were made were flattened and hid till the next game.

Making of dolls and their belongings was controlled by senior female relations. The girls were prohibited to copy other girls’ dolls and to create characters imitating specific individuals. A doll could not have any traits of a specific person lest it received his/her soul. A constant doll, moreover having a name, was believed to be able to absorb part of a living person’s soul and do harm to his/her health.

Each Khanty girl used to have her own needlework and doll bags. The former contained things necessary for sewing and the latter had dolls’ clothes and molds. In fact, the toy was not the mold but the clothes used to dress the mold, every time in a new fashion. This is why the doll was very flexible. It could change clothes many times to depict different actions. Toy dresses, scarves, and sakhi (Khanty upper clothing) did not belong to any particular doll and were common playing property. During different game stages the doll would have a proper name or an appellative name, or both.

Dolls’ clothes used to be decorated with traditional materials, buttons, and ribbon and fabric applications. Nerym Yakh usually sewed buttons in rows on narrow and wide stripes of fabric attached to the sakhi’s laps and foreparts whilst the “village” and the “river” Khanty used buttons to embroider clothes. In the marshes, they kept making fabric scarves with tassels and “old-fashioned” (straight tunic-like) dresses for dolls until the 1960s, longer than in other localities.

Nerym Yakh dolls fall into two large categories: plant-dolls and people-dolls.

Plant-dolls

Almost all plant-dolls were made out of fabric and thread. The plants included a variety of trees, berry bushes, and swamp-growing berries.

A tree-doll (yukh pakyt) was made from a piece of fabric twisted in a roller and folded in such a way that the lower part served as “legs” and made the figurine stable. A characteristic feature of yukh pakyt is long hair in tresses, made from thread. In games, plant-dolls were always immobile, they could only stand still and perform the function of scenery.

Berry-dolls (kanek pakyt) were also made out of fabric. A small bit of fabric shaped the head, which was stuck through a cut in a rectangular or square patch-scarf and fixed with thread around the “neck”. Such a doll had no hair and did not move much either—as a rule, it used to sit with the dress lap smoothened around it.

Among the berry-dolls the cloudberry in a red scarf made a figure. The reason for this was that the cloudberry was considered special: it was the earliest and sweetest among all berries. There used to be a folk custom to put a special red scarf on the biggest cloudberry found during the first berry-picking. In fact, proper berry-picking did not begin until such scarf-giving was observed.

Dolls made from grass (pom saveli, a bluegrass plait) formed a separate group. The grass-dolls were made from long bluegrass culms folded in half. An indispensable attribute of such a doll was its grass plait that played the role of support: with its help, the doll was held in the vertical position. As a rule, these dolls were many—they were arranged in a dense line depicting growing grass.

Grass-dolls used to be placed next to berry-dolls. The cranberry doll was the permanent neighbor of the grass-doll because they were both characters of the same fairy-tale. The fairy-tale went that once upon a time there lived two friends, Cranberry and Grass Plait. Cranberry was a hard-working craftswoman, and Grass Plait was very lazy. Exasperated with her friend, Cranberry left for the marshes. Grass Plait, starving without her friend’s support, went to the marsh to look for her and stayed there as bluegrass, which warms the cranberries until the spring comes.

Sokh pakyt: people-dolls

Sokh pakyt were made both from fabric and natural materials (grass, skins of small animals, birds’ wings, tails and feathers). Nerym Yakh people-dolls had gender and, surprisingly, age: there were boys and girls, men and women, old men and old women. Age groups were referred to appellatively based on the dolls’ functions: ko was a young, strong, and good-looking man; pyrs ko was not a young but strong and well-groomed man; pyrs iki was a slovenly old man; auveli was a pretty girl; auvol inki was an agile, casual, and naughty girl; paerl inki was a boy; and par perry was a slovenly and lazy boy.

Dolls were called by their occupation or place of residence: nerm ne and nerm iki were adult man and woman living in the forest, voch ne and voch iki were adult man and woman living in the town, voch kor ai ne (literally, “a girl walking along town streets”) was a town beauty.

When natural materials were used, the dolls became zooanthropomorphic: a bird-man or an animal-man. Such toys were mostly of the male gender—boys, young men, adult men, and old men. Sometimes they had appellative names coinciding with the names of the animals (plenki was a mouse, kucher iki was a chipmunk, ok iki was a male fox) and their traits of character. It was a taboo though to give the toys the names of the kin’s totemic animals—Moose, Bear, or Beaver (depending on the kin of the players).

“Male” dolls were usually made from fur and leather, and fabric was needed only to make tunic-like shirts and scarves serving as mosquito head nets. Often, whole skins of small animals like squirrels or chipmunks or skins ripped from paws and heads were used.

Horror dolls

The role of these Khanty dolls was totally different: horror dolls were not toys but a way of abusive communication, a kind of strong language—in fact, they assumed the humans’ speaking functions. Since traditional culture prohibited abusing somebody verbally, the abusive function was performed by a horror doll. Adults did not allow the children to make such dolls or to show them to anybody—in the same way as we forbid our children to use violent language.

As one could not reply the insulter (a doll character or a human friend) verbally, they would show him a horror doll, identifying the doll with the offender. “When younger brothers and sisters disobey or an older sister is stubborn, instead of scolding or beating them, you can show them a horror doll, which is interpreted as a threat, ‘you’ll have crooked arms like that because you are fighting!’”, explained one of the Nerym Yakh consultants.

A horror doll could be slipped (but never shown face to face) to an adult as protest against an unfair (from the child’s point of view) punishment. Sometimes such a demonstration provoked laughter, but more often lead to further disciplinary measures. Men (father, grandfather, or uncle) were usually slipped a punykh iki (hairy man) or nerym okh (a marsh head). These dolls were made from crooked dry fir (or sometimes birch) branches, with fir lichen twisted around them.

Typical horror dolls were pom kot imi (a moss woman), companion characters porsa ne (a cheerful girl who does everything quickly, sloppily, and spreads herself thin) and torsa ne (a trumpet-tongued and easily amused girl who would rather sit idly than do any work), kolh porekh imi (a horrible woman sitting at a tree stump or fir tree), lanet ne (a hurriedly walking woman), lapsa ne (a woman whose clothes are too loose), and companion fairy tale characters kunvan and tuivan (who overheard and spread gossip), which during the game sometimes acted as servants of the older spirits or gods.

Standing by itself was the horror doll por ne (the bad slovenly woman living in the forest). She was, in fact, an idol, a figurine of a spirit, a Khanty ogress. This doll could not be disassembled as it was made of small scraps. If the adults discovered this toy, they gave the girls a hard time: in the presence of such a doll at home, moreover at night, god knows what might happen.

As a rule, the person who possessed and made horror dolls was also a bit scared of them. In order to keep herself safe, she would say the following “spell”: “Let them do no harm to me or anybody else! Let them be my protection! We’ll be together!”

Small horror dolls personifying monsters and evil spirits were made from wild rosemary, fir, or dog rose branches that resembled in shape a human being or an animal: vague, not pronounced, zooanthropomorphic features of horror toys helped to emphasize their evil nature.

Nerym Yakh fairy talesfor Surgut children

Popularization is a topical issue for any museum in any time. The Surgut Regional Museum of Local Lore, actively engaged in popularizing the cultural heritage of indigenous population, has chosen an unconventional popularization technique, an ethnic puppet theater. It gets across to different age groups: both children and their parents enjoy its performances.Of greatest value is interaction with physically and mentally disabled children—those suffering from locomotor apparatus disorders, impaired hearing and sight, and early children’s autism—who attend special schools and the local rehabilitation center called Dobryi Volshebnik (Kind Wizard). Museum personnel not only allow but make children touch the dolls so that they can get an insight into their images and imitate their actions.

Working with children became possible thanks to the project “Nerym Yakh Dolls and Fairy-tales” which includes familiarizing children with the Museum’s collection of ethnic dolls dated mid last century, watching the performance of the Puppet Theater “Surgut Tales of Marsh People”, and discussing the fairy-tale plot after the performance. The ethnographic materials become even more attractive thanks to master classes during which children make dolls for new performances and act as puppeteers.

The author and editors thank L. L. Frolova, head of Studies and Education Department, Surgut Regional Museum of Local Lore, and A. V. Zaika, an employee of the Museum, for their assistance with preparation of this publication.

The photos used in this publication are from the archives of Surgut Regional Museum of Local Lore and courtesy of A. Zaika

* Surgut region of the Khanty-Mansi autonomous okrug is home to 2,940 Khanty, or 10 % of this nationality

** Yakh (people) denotes arbitrary kinship based on geographical location. Yakh is characterized with particular landscape and trade features, which form a specific material and spiritual culture