"Semi-Finished Mother-in-Law" With a Chain Saw. How Siberian Aborigines Combine the Old and the New

The author of this article, explorer of the indigenous nationalities inhabiting northern West Siberia Vladislav M. Koulemzin, has participated in dozens of expeditions and has often spent months among indigenous population, living under their roof and sharing their meals. Today, Vladislav relates his observations made over many years and comments on the intricately interwoven features of the traditional, almost Neolithic, and modern way of life

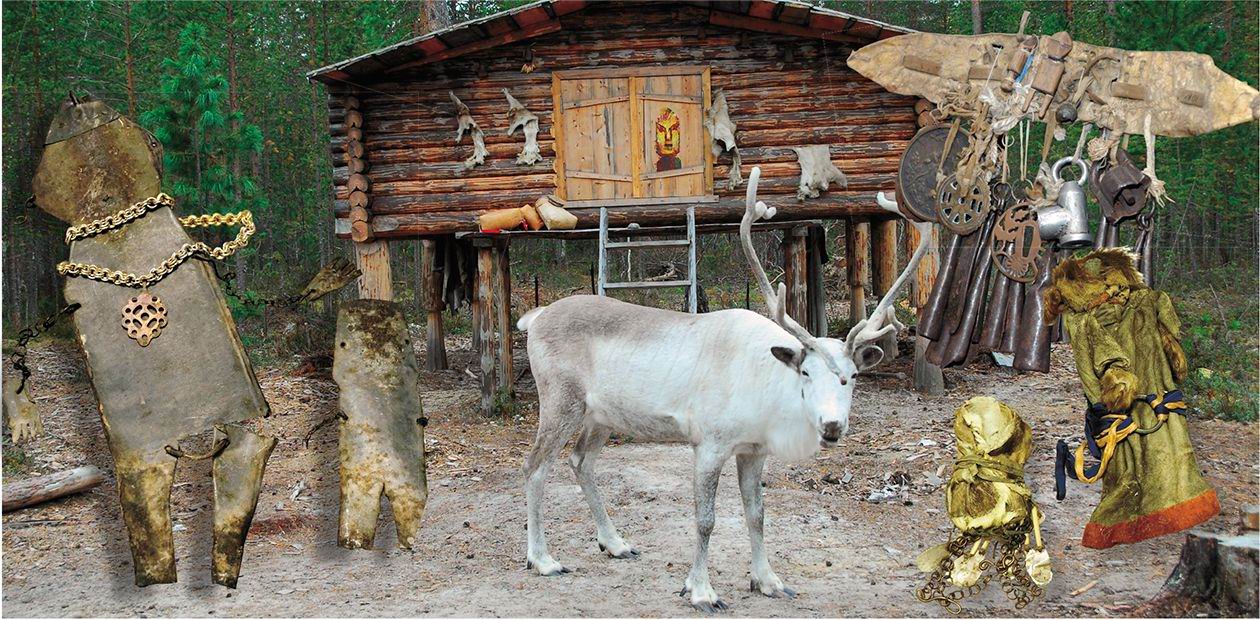

Ihave been taking notes sincethe 1960s, when the USSR greeted its new heroes—cosmonauts. In those days, they used to deliver some “cultural” things, totally unnecessary for the northern Siberian population, to local stores with a view to “enlightening retarded nationalities”. It looked utterly ridiculous but I was always impressed by the clever and even “innovative” applications the Khanty, Selkups, or Kets, living at their camps in perfect harmony with their cold forests, marshes, birds and animals, found for these knick-knacks.

Isn’t surprising when a numbered disk from the lotto shoots out of the gun barrel and hits a squirrel without ruining its skin? This kind of the “right bullet” was used in the 1960s—1970s by the Khanty, Selkups and Forest Nenets—their ancestors used to have blunt-pointed arrows and a bow to shoot squirrels so that the precious hide remained intact.

And why on earth would a store at a god-forsaken hunters’ camp need a gymnastic hoop? Clear as a day: this apparatus designed for waist-building of unapproachable beauties made an excellent spear shaft when the aluminum circle was straightened and cut to pieces. It was no problem to drive a point made of stone or mammoth tusk into this light and hollow tube shaft.

In a word, practically all supplies intended for the remote North, in line with the five-year plan of the Soviet government, were in demand including the English-Russian dictionaries and ladies’ felt hats. Both of these were used to make quality wads for guns.

It goes without saying that representatives of the most ancient trades—hunters and fishermen—do not lack for resourcefulness. One day (it was in 1963 during the expedition to the Narym krai headed by the well-known ethnographer specializing in the Selkups G. I. Pelikh), under the sacred cedar tree at a Selkup camp, we found a tambourine beater with the solar sign glued to it—and the sign was made out of a clock wheel!

A Nenets hunter replaced the tip of a worn-out rubber tube of a boat motor with … skin ripped off a goose foot.

Empty barrels discarded by the oilmen served to make pontoon-bridges, stoves, and smoke-houses for smoking fish and meat.

Electric iron and electric furnace insulators were the best pendants for jackets.

A lucky find for a needlewoman was bits of electric wires in bright insulation: the wire was drawn out and the insulation tubes cut into pieces, which made smart beads for embroidering clothes, footwear, and mittens. The colors of such beads did not fade in the sun or in the frost!

One time, in the late 1960s, a serious Khanty hunter came to me to talk. He was aware of the spacecraft going high in the sky. Also he knew that the frosts up there were even more severe than in the upper reaches of the Vakh river (a tributary of the Ob). And he asked me to pass on a piece of advice to the cosmonauts: spacecraft parts should be smeared with grease produced from the deer shin-bone—the Khanty have been using this grease to lubricate their gun-locks and these worked perfectly despite any frost.

And there goes another “innovation”. The Khanty hunters use glue made in a traditional way out of winter crucian scales, sterlet float and moose horns. This glue is applied to paste fur to skis as its smell attracts the cautious sable (whereas the smell of any modern glue scares it away). It has been found out that the guitar sounding-board glued with this traditional glue produces a softer and richer sound.

Also the hunters noticed that in a heavy frost a trap makes a sound not perceived by the human ear but very well heard by animals. However, if you cover the trap with a paper napkin, it will be “silent”.

And here is a remarkable observation made by the Yenisei Kets. They noticed that the moose would not go near high-voltage lines. Moose traces crossing a line signal that the wires have been torn. And in this case, the Ket hunters (contrary to the electricians) rejoice: the noise produced by the voltage lines, same as noise coming from river navigation, restricts the animals’ freedom of movement, which results in “incest”. The Kets realize that accidents are good for their herds.

Today you can see some truly amusing things. For example, here goes a hunter who sets a trap invented back in the Neolithic times. He makes it with the help of a knife—all the rest that is needed can be found in the forest: a cedar root serves as the rope, a stone goes for the counterweight, and a dry fir branch makes the shaft of the bow. Having set the trap, he takes a mobile out of his pocket and calls home to warn the family of a storm approaching: the capercailzie have been flying from the edge to the heart of the forest.

And this woman has exchanged three sables for a chain saw and is now learning how to use it. The matter is that division of labor with Siberian aborigines follows the sex and age principle. Hunting and fishing are men’s occupations, and all the jobs involved are done by men. Cooking is for women, and, as a result, chopping firewood is women’s work. The women’s ax is big and heavy because it is used to chop blocks (the men’s ax is small, and the head of the family takes it when he goes hunting and carries it on straps behind his back), whereas a chain saw is lighter and quicker. I once watched a young lady sharpening the saw chain with a file while her husband was sitting nearby, tranquilly observing the process.

All the life and work of small nationalities focuses on their future and survival. Since their green days, children should not only absorb all traditional skills but also learn modern things so as to be able to adapt to the present and future. It is not by chance that in the Mansi language “daughter-in-law” literally means “semi-finished mother-in-law”. She is yet to become a mother-in-law, and for the time being she is bound to give birth and raise girls, who later, when she becomes a mother-in-law, will give birth to other Mansi!

In 1998 an international conference of traditions and innovations used by the hunters, collectors, and fishermen was held in Sapporo, Japan. It was generally acknowledged that the most interesting material was presented by the scholars specializing in Siberian studies. Maybe sometime such a conference will be held in Siberia?

The editors are grateful to Doctor of History A. V. Baulo (IAE, SB RAS), Candidate of History I. V. Salnikova (IAE, SB RAS), and researcher K. A. Sagalaev (Institute of Philology, SB RAS) for their assistance in preparing this publication