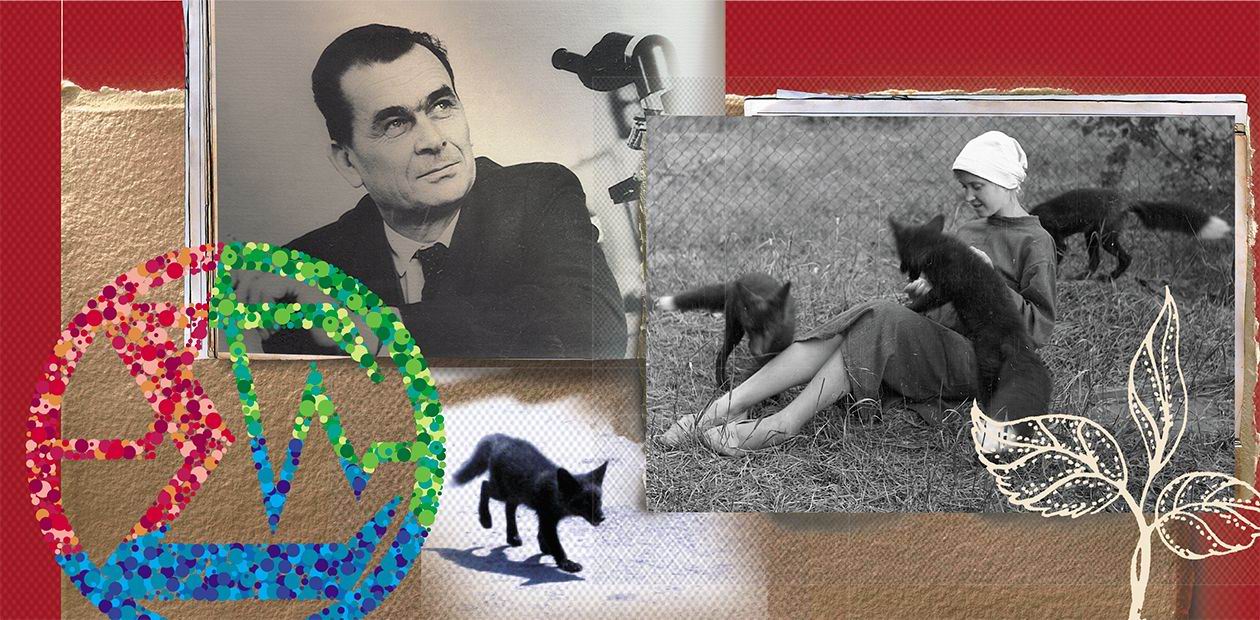

Dmitriy Konstantinovich Belyaev

Brush strokes in the portrait

I have wanted to write about my father, an outstanding geneticist and evolutionist, Dmitriy Konstantinovich Belyaev, for a long time. There are a number of reasons. Apart from my natural desire to collect memories and a promise given to my mother, Svetlana Vladimirovna, I came to realize that his life could be of interest to many people, and not just my children and, perhaps, my grandchildren…

In the wonderful book by B. Hare and W. Woods, “The Genius of Dogs,” published in 2013, there is a line: “There is hardly any information on Dmitri Konstantinovich Belyaev. There are no biographies on his life, other than a few eulogies. After Belyaev`s death, his wife published a book of memories from those who knew him, but this was distributed only among friends and colleagues, and it is impossible to obtain a copy.” This statement is not entirely accurate, although the book was indeed a small print, and it was never printed again. A lot has been said about my father – in articles, books and the Internet. Yet people tend to focus on the results of his famous evolutionary experiment and say very little about his personality. Unfortunately, the little they do say is full of errors. I would like to correct that. After all, many people, especially young people, ask me about details of my father’s life, which I thought were well-known. But this is not so, and I must answer these questions here

Dmitriy Konstantinovich Belyaev: a Book of Memories (2002) is a collection of memories of Belyaev’s friends and colleagues, journalists, and war veterans. It was published by the effort of several people, especially my mother, Svetlana Vladimirovna Argutinskaya, Vladimir Konstantinovich Shumnyi, father’s comrade and friend, and Professor Pavel Mikhailovich Borodin, who had worked with my farther for many years.

ABOUT MYSELF I graduated from the Department of Natural Sciences of Novosibirsk State University with a specialization in Biology in 1972. In 1972—1991, I worked in the Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the SB AS USSR: started out as a senior lab assistant and eventually became a senior researcher. L. S. Sandakhchiev and V. G. Budker, both outstanding biologists, were my teachers, and I am deeply grateful to them. But most of all I am grateful to my father, Dmitriy Konstantinovich Belyaev, for his advice and constant support.From 1991 through 2000, I worked in the University of Birmingham in Great Britain; from 2000, I have been working in the Institute of Cellular and Molecular Biology in the University of Leeds in England. My professional interests focus on epigenetic regulation of gene expression in neurodegenerative diseases. I have the degree of a Candidate of Biology and authored over 80 research works

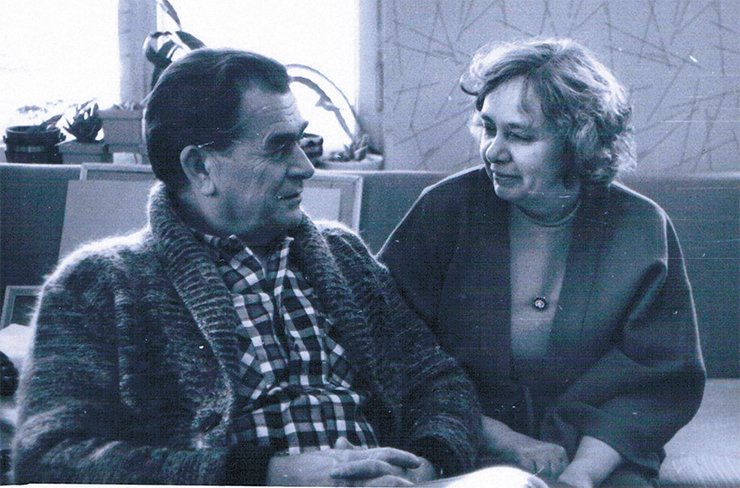

My dear mother wrote a chapter about the father, titled “Dima”; it is the first chapter of the book. It is written with endless love and respect to my father. It turned out to be a wonderful tale of love written by a nearly octogenarian woman. Pasha (P. M. Borodin) and I were invited to edit the chapter. We were unanimous in that the writing was too pompous – something the father never liked and would not approve. But my mother, so old and frail, just listened patiently, looking at us with her kind blue eyes, and did not object much. In the end, she did it her way. And she did the right thing, because the chapter was great. By the way, it was my mother who began to call my father “Dima.” The family called him “Mitya” [another diminutive of the Russian name Dmitriy]. It is interesting that my relatives and my mother decided to name my brother Misha, while my father wanted to name him Ivan. The relatives were insistent, and my father gave way, but he called my brother Ivan all his life.

I have received a number of proposals asking me to write for this book, and I even started writing a few times. But each and every time I eventually realized I was writing about myself – and I did not want that. I am more than reserved in my opinion about my writing skills and I gave up after several attempts because I thought it was better not to write anything at all than write badly.

But time flies. I have reached my father’s age. And I decided to write about him as well as I can. Will I be subjective in my narrative? No doubt. Otherwise I would not be my father’s son. I stress that I am writing for my children and for anyone who may find it interesting. I believe I am free to write what I consider necessary and possible.

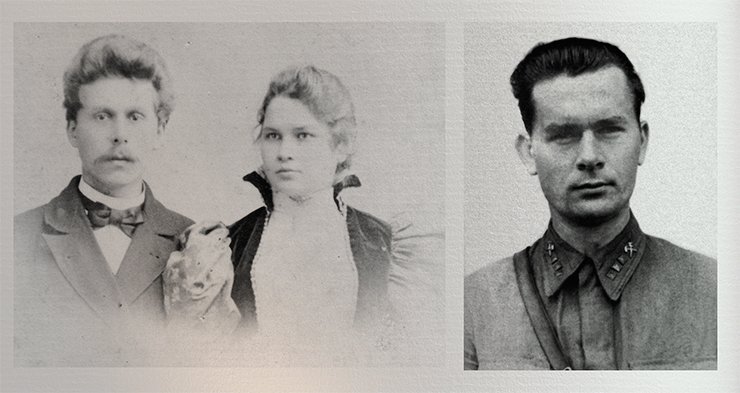

Family and environment

It is a commonly accepted opinion that my father was exiled to Siberia for disagreeing with the regime and for being an advocate of classical genetics. But this is not true. He was offered a position by the founding director of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, N. P. Dubinin, and he did not hesitate a moment.

He left military service in 1946 and became a laboratory head in the Research Institute of Fur Industry in Moscow. From 1957 – head of evolutionary genetics laboratory in the new Institute of Cytology and Genetics of the SB AS USSR in Novosibirsk. From 1959 through 1985 – director of the ICG SB AS USSR. From 1964 – Corresponding Member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, from 1972 – acting member of the Academy. 1975 through 1985 – deputy chair of the Siberian Branch of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. From 1978 through 1983 – President of the International Federation of Genetics

An amusing fact: in his story about my father, G. Paderin, a writer from Novosibirsk, wrote: “Dmitriy Konstantinovich told his wife that he was invited to Novosibirsk to run a laboratory in Dubinin’s institute, and she suggested that he should see a psychiatrist.” These words made my mother deeply indignant, a feeling that lasted for years. Naturally, she never said anything like that. On the opposite, she realized right away that this transfer would be an excellent opportunity for my father to practice science and would provide a very decent apartment for the family. Back at the time we were living in Raisino, on the outskirts of Moscow, in a tiny two-room Finnish house with a wood stove, an outhouse and chickens in the backyard.

The very expression – “see a psychiatrist” – was absolutely impossible and unacceptable in our family. The atmosphere in our family was dignified and calm, if not idyllic. We all understood how busy the father was and tried to help him to the best of our ability. Our parents did argue at times, but never lost dignity. My mother adored my father, and I dare say that he owes much of his lifetime success to her. He understood that, cared for her and loved her very much.

Father never openly disagreed with the regime. He went through the war and directly experienced lysenkovschina [state research policy based on the teachings of the influential Soviet agriculturist and geneticist, Trofim Lysenko, who rejected conventional Mendelian theories in favor of selection based on acquired traits, which was ideologically attractive for the government]; after the infamous VASKhNIL session [VASKhNIL, ВАСХНИЛ, a Russian acronym for the Lenin All-Union Agricultural Academy] he lost his position, but was reappointed right away. He was never afraid of anything or anyone but realized clearly that open dissidence would ruin his laboratory in Moscow and eventually lead to the termination of the Institute in Novosibirsk. He remembered all too well what had happened to his brother Nikolai. I take the liberty of reminding the reader the story of Nikolay Belyaev. He was one of the brightest students of N. K. Koltsov, a brilliant geneticist. Together with Koltsov and N. V. Timofeev-Ressovskiy he was invited to Germany, but ended up in Tashkent, because he was already under suspicion of being of clerical descent, probably due to activity of informants. Nikolai left for Tbilisi, only to be slapped by more informant reports, this time from Georgian geneticists. In 1938 he was sentenced to death and executed.

Father never expressed any agreement with the regime, either. He stayed out of the Communist Party his whole life, and did not sign even one of the public letters against A. D. Sakharov. He never made a show out of it but always managed to find a way not to sign those petitions. He knew the rules of the game, though, and did not want to harm the institute, so he stayed on good terms with the Party officials. Luckily, the local officials in Novosibirsk and in Akademgorodok in particular were quite reasonable and adequate people.

Another episode is described by R. Pimenov, a famous dissident mathematician, in his memoirs. His father, I. G. Scherbakov, who was one of our neighbors back in Raisino – a man who had spent quite a lot of time in prison camps after the war and was an ardent dissident even back in Stalin’s lifetime – asked my father for a favor: to bring a Knuth Gamsun’s book, which was considered anti-Soviet at the time, from abroad. Father went to Scandinavia for three months with a delegation to study fur farming and to negotiate the possibility of exporting fur. Father bought the book and brought it back. Actually, he did a lot of things he was not supposed to do. P. M. Borodin recalls an episode when father brought a cage with long-tailed roosters from Japan. It was risky; something not anyone would dare try. Father’s spirit always had a rebellious element to it…

His attitude to religion was that of a decent, educated person. He was a son of a priest and could not but treat religion with respect. He knew the history of religion well, and quoted the Bible sometimes. However, he did not observe any church rituals: he did not go to church and did not pray. There were no icons in the house. But I believe he did have an understanding of God in his soul. He used to say he could not comprehend the origin of butterfly colors without the Creator’s intervention.

Regarding his attitude towards Stalin, I assert that for as long as I remember myself (and I remember myself from the time of Stalin’s funeral, i. e. from when I was four) my father always said Stalin was a bastard. That is precisely what he said. I grew up with it and never questioned it. He could not think any different, having lost his brother who he loved deeply. His father, a priest, was dekulakized; his house was torched, including a wonderful library.

Father took all attempts to exculpate Stalin very painfully. When I. D. Bodul, the First Secretary of the Moldavian Central Committee of the Communist Party, gave a speech at one of the Party conventions, filled with curtseys for Stalin, father became very worried and showed this speech to everyone. People tried to calm him down: “Who is this Bodul, anyway?” “Bodul may be a nobody, – father replied, – but he does not speak for himself; he has been allowed to say these things today! Tomorrow, Brezhnev will repeat these words.” In essence, this is what happened.

A few words on arts

Father is usually pictured as a sort of an academic general, and it seems that we all, including the family, are partly to blame. After his death, mother asked for a favor – that a copy of Tvardovskiy’s poem, “Vasiliy Terkin,” be put on his table in the memorial room in the Institute. Indeed, he loved that book and knew parts of it by heart. This is what probably produced the opinion that he liked exclusively war stories, poems and songs. However, I must say he was a brilliantly educated and eclectic man, and arts were not an exception. Father excelled in his knowledge of literature, music and fine arts. Our home library, in my opinion, was larger and better than any other home library I have ever seen. And the books were not there for decoration. In a way, father was a self-made man. He used to quote both prose and poetry all the time: in his speeches, in his papers, and in daily life. The choice of authors was eclectic: Russian poems and Burns, Zabolotsky and Lugovskoy, Bulgakov, Chekhov and Mayakovskiy.

Lifestyle

In my father’s lifetime, I was unhappy with him for two reasons – and it was not only I: so were my mother, our family and our friends. First, he never wrote down anything – or barely anything – from his thoughts on evolution. His work gained worldwide recognition only because of the efforts of Lyudmila Trut, his student and follower. Still, his lectures were stunningly captivating and it was a sheer pleasure to listen to him. He was always happy to teach as long as people listened, but he never wrote anything down. He may have thought he had time and expected to live a long life. His mother lived to 92 and some relatives passed the centennial mark. But he did not.

The second reason is that father never took care of his health. He was essentially a healthy man, and neither his heart or his blood pressure gave him any trouble until he was around 65. But he was a chain smoker, although he did make a few half-heated attempts to quit. He never got any exercise and virtually never walked and did not acknowledge any sports. Our pleas to take his health more seriously never caused anything but irritation: “Where am I supposed to find the time for this nonsense!?”

We had a beautiful garden around the house where we lived. Father would sometimes sit there, but he never worked in the garden – he said he had toiled enough in his childhood. Indeed, he grew up in a rural area and had quite a few skills. He knew how to cut grass with a scythe, but he never did any gardening. There was no use trying to make him do anything, no matter what it was. Everyone remembers that.

All this is exceptionally frustrating. Father had so many plans and wishes. One of them was the Cherga project, which he cherished. He was obsessed with the idea of creating a nature reserve for endangered animals and found a place in the Altai Mountains near the village of Cherga. The task was a complex one and required time, effort and good people, all of which was hard to find. Even though the idea of creating the reserve was supported by the head of the Siberian Branch of the Academy of the time, Academician V. A. Koptyug, the concept itself encountered criticism and lack of enthusiasm: who needs this sort of thing?

On many occasions the father demonstrated a lot more visionary insight than others around him did, and this was the case with Cherga. Cherga was his dream, the purpose of his life in his later years. He breathed the dream. But he did not have the time. And he is partly to blame.

He worked a lot and was always busy with the Institute management and research issues. Unfortunately, not all of these things were necessary and useful. He had to deal with conflicts, both local and those coming from Moscow: he rushed to help people who then wrote atrocious things about him. He had to attend the sittings of Gorisporkom (the municipal executive committee) because he was an elected member of the city council. He used to tell funny stories about those sittings. Usually, a good half of the members tried to play hookey during the first break, and for this reason, the сoat-check was closed and they would not hand out the coats. But father used to leave his coat in the car, where his driver waited for him. In the morning, all members checked in, and during the break, father pretended to go for a smoke and left. He said that listening to the jibberish in those sessions was unbearable, and he was very proud of his shifty trick. Actually, father had quite a lot of such stories.

If they asked me how he spent his free time, I would answer – working and chores. He had no free time, no hobbies, such as stamp collecting, to speak of. He did not collect edible mushrooms and did not hike in the woods.

His old friend and one of his first economic deputies, Mikhail Nikitich Zhukov, sparked his interest in fishing.

Father got into it, and bought a motorboat. Together with the Kerkises and the Rauschenbachs, father’s colleagues, we went sailing on the Ob reservoir and the river Berd’ with all its inlets. We went with our families, fished, swam and had basket dinners. Here, father excelled as well. He was a skilled sailor. Once we got into a storm, and a serious storm it was – I was certain we would capsize! – and he steered clear of danger. In the early 1960s, he bought an actual small cutter, with a steering wheel and cuddy. But I never even saw it – father got too busy at work and did not have time for it anymore.

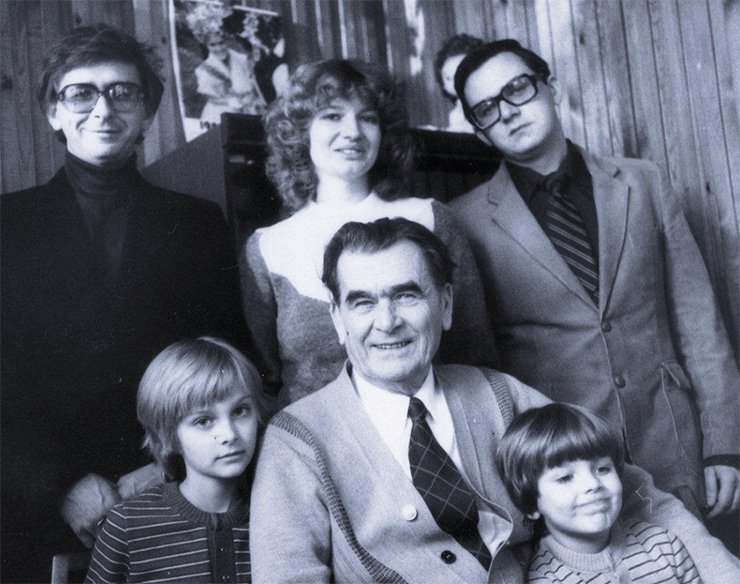

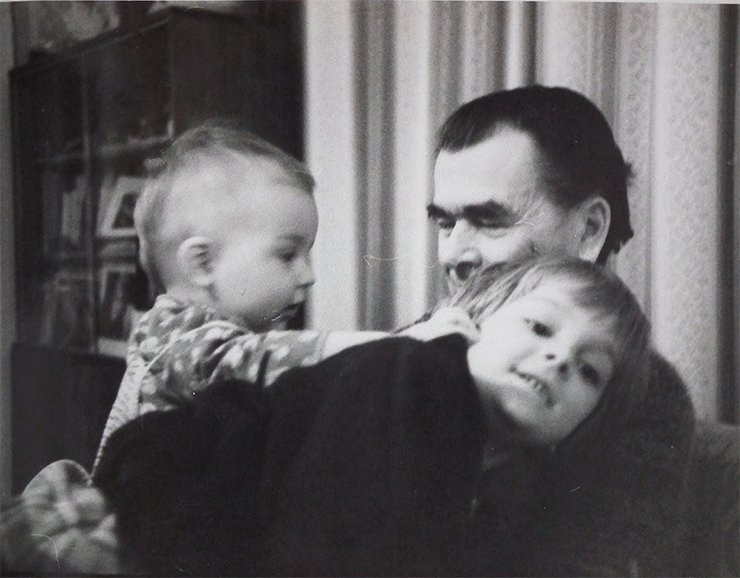

He usually returned home around eight, and often brought along friends or colleagues. We had dinner, talked, usually about the Institute business. Sometimes these talks were meant to stay confidential, and we all understood it. When grandchildren were born, he always tried to spend more time with them and rushed to see them before dinner when they were still up. He was very close to my daughter Ekaterina and treated her as an equal. I must say, my father never liked routine chat. It was not forbidden, yet we all strove to talk about things that were truly important and serious. That was normal in our family.

Sometimes he would watch a soccer game with me – or at least tried. I loved soccer and tried not to miss it when it was on TV. Unfortunately, my father’s behavior is impossible to describe. His face and his words bore a mixture of some interest and an ironic attitude. However, the interest faded quickly. Father would conclude the players were worthless or could find better and more useful things to do in life. He left for his study and worked until two past midnight, or read books. He loved Russian literature, including some relatively obscure writers, such as Leskov and Melnikov-Pecherskiy… The latter he read shortly before death, knowing it was inevitable, and faced it calmly, still immersed in his Institute business. He knew and loved Anatole France, a writer gone into oblivion in our days. He made me and my wife, Tamara, read all eight volumes of his works. I cannot say we regretted it. On the opposite, Tamara often says that it was my father who acquainted her with Anatole France.

War

Memories of the War were sacred for my father – please forgive the pathos. Starting around April 30, he would begin recalling: “Zhukov moved the forces there, and Konev went there… on May 3, they took Berlin… so many people were killed…” He knew the history of the War until the last day.

On May 9, he would put on all his medals and go to the veterans parade in Akademgorodok, where he always was one of the prominent figures. Yet he did not like to talk about the war. Sometimes he would tell war stories and anecdotes. For example, in 1945 they ended up in a place controlled by Germans and they had to cut and run. In another story, General Beloborodov, who would later become the commander of the Moscow military district, wanted to execute him. It would be a funny story, were not it so scary.

It happened in Belorussia in 1944. Father was driving on a frozen crust across bogs when another car caught up with him and signaled, demanding that he make way. There was nowhere to turn, because they were in the middle of a bog. They reached solid ground and got out of their cars. Beloborodov, who happened to be in the following car, yelled:

– I will execute you!

– As you wish, Sir General!

– I will shoot you right here, right now!

– As you wish.

– Okay. Go, major (father was already a major then), and tell your unit commander to put you in detention for ten days!

Father did not tell anything to anyone, quite naturally. Later, he met with Beloborodov. They both remembered this episode and had a laugh, although for my father, it was no laughing matter back then.

When he spoke about the War, he said it was all blood and dirt. There was nothing even remotely romantic about it. He would remember a shed in Belorussia, and what they saw there after the Germans had fled, and go silent. He said: “I cannot talk about it.” And he never did.

Father blessed me and sent me to the army when I was recruited. We did not have a military department in our University, and by law I was obliged to serve in the army for a year after graduation. Father helped quite a few people to avoid enrollment, but he told me: “I will not help you. Army will do you good and it will build your character.” I honestly replied that I was not planning to dodge. Together with my mother they went to see me off at the train station. I served in the Air Force in the Krasnoyarskiy Kray. And what a place it was: at times, the temperature plunged to minus 50 degrees Celsius [–58 Fahrenheit]. We had to dig ditches and fill them with earth again, or shovel huge mounds of snow only to put it back where it had been in the first place – the usual army routine. But I made real friends there who I still love a lot. In the army, I came to realize how I loved my father and mother and how much I missed them. I went to see them when I got a three-day leave warrant, and father was utterly happy to see me.

My current thoughts about my father

I had an intention to write about the people who wrote reports and complaints about my father – such things happened, too. But on second thought I decided not to do it. I do not want to mix the good and the bad in one pot and remember my father along with these people. I do not want to translate my writing into criticism and negativism. In essence, history has put everything in its place, and I have got nothing to add to it.

If I was asked to describe my father in two words, I would say that he was an extremely serious man. This means a serious attitude to the things he served: to genetics, to his own work and to the work of other people, to the Institute, which was always in his heart and mind; to his responsibilities, which were numerous, and quite absurd at times; to his family, which always needed his help; to his friends, whom he loved endlessly, protected and supported to the best of his abilities. He did it all selflessly and unsparingly. I can feel the pathos here, but it is the truth and there is no other way to put it into words.

This does not mean my father was a gloomy and morose man, although it did happen, especially near the end of his life. He had a fantastic sense of humor: when he laughed, you could not imagine a man more amiable. He used to say that people completely devoid of the sense of humor bothered him. When he was in a good mood, the Institute meetings, seminars and research councils sessions turned into a perfect drama theater.

I remember one of those sessions. I have never worked in my father’s Institute, even though I was and I still am a biologist, but I had many contacts in the Institute. I happened to be there because our work with O. L. Serov and his team had made us popular. It was late afternoon but there were still a lot of people present. I think it was a research council session of the Siberian VOGIS (ВОГИС – a Russian acronym for the Vavilov Society of Geneticists and Selectioners), where father, as its chairman, was handing out various awards. There were several awards and father was in a great mood.

– Okay, – he said, holding on to his cigarette, – here is a VDNH certificate (ВДНХ – Russian acronym for the Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy) awarded to R. I. Salganic (a famous biochemist and deputy director of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics for many years) for his series of work on nucleases. Rudolf Iosifovich, you owe us a drink!

– Will do, Dmitriy Konstantinovich.

– A bottle of Cognac!

– Sure, sure, sure.

– Don’t procrastinate.

– Of course not!

– Here, take your certificate, maybe you can hang it where it belongs…

Next.

– A VDNH medal and a monetary award goes to O. L. Serov for his work on chromosome transfer. Oleg, are you here? Where is Serov?

– I’m here, Dmitriy Konstantinovich.

– Here you go. A medal, and the money up to you. Wait, what’s that work? Is this what you were doing with Nikolai?

– Exactly, – Serov says slowly and soberly.

– Okay, pin it to your suit, here, come and take it, and it’s up to you with the award. Call me, I’ll help.

– Okay, Dmitriy Konstantinovich…

Actually, father took these sessions very seriously and took a lot of effort to prepare for them. He never read from paper but always drafted his speeches. And his speeches were amazingly good. On many occasions he scolded me for my inarticulacy, and that was fair criticism.

Father had a striking voice, a beautiful baritone. He used it masterfully, could change its tone or hold a pause when necessary and always kept his audience hooked, like a good actor. No surprise he was a relative of Kastorskiy, a famous bass singer in the Mariinskiy Theatre in St Petersburg early in the 20th century. Kastorskiy was viewed as an equal of Shalyapin, and my wife plays his records to our guests, claiming its Dmitry Konstantinovich voice. And it is, indeed, similar.

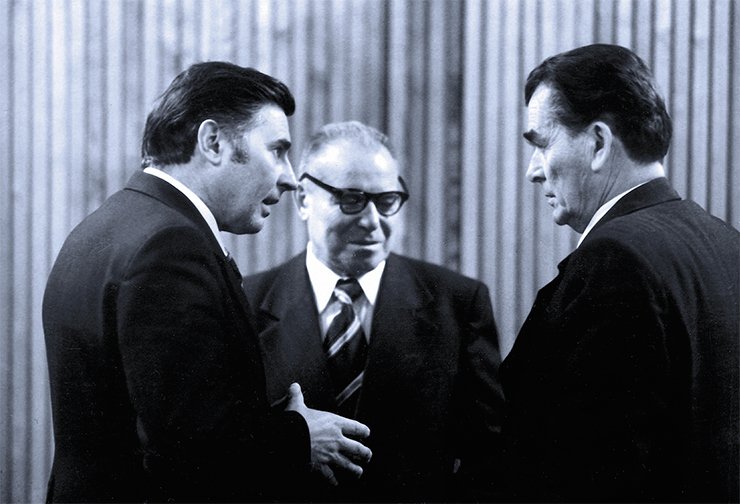

Father loved his friends and treated them with tenderness. He constantly said that there is no bond holier than friendship and followed this principle to the fullest. At this point, I should recall his closest friends: B. L. Astaurov, B. N. Sidorov, N. N. Sokolov, V. V. Sakharov, V. V. Khvostova, V. K. Shumnyi, L. V. Krushinskiy, V. I. Evsikov, L. S. Sandakhchiev, P. M. Borodin, A. O. Ruvinskiy, N. B. Khristolyubova. I ask for apology if I have failed to mention somebody.

He loved just to spend time in a company of close friends or discuss serious Institute business, and sometimes his friends would face the music – which was not always deserved and fair. But they loved him and did not hold grudges for long. Father believed that one should always tell the whole truth to a friend, otherwise you are not such a good friend yourself. Sometimes the friends would talk back, and father, in turn, would not be very upset.

Another episode. Once father came home in a rotten mood. My friend Pasha Borodin had dropped in to see me. Father attacked him: “Aha, there you are, my dear. What’s with all the mess on the farm? The cages are all torn, the sheds are broken, and you are tight as a clam!” “How would I know? I never even go there.” Father got even more upset. “And why don’t you know what’s happening on the farm?” “[X] is supposed to be taking care of it.” “Outrageous! – father says, – these are your comrades, your lab, and you are hiding behind their backs? This won’t do!” I interfered: “This is unfair, why are you scolding Pasha? Find the people responsible for all this.” This is when I caught it bad for aiding. Father went on: “This man, [X], is he your friend? I will fire him if it all goes on like this, for heaven’s sake! He is a loafer and an empty man.” Pasha and I defended the man, of course. Father continued: “You are not his comrades if you cannot tell him the truth. You must be the first to tell him he is lazy and that I am going to kick him out. Tell him.”

We did not tell him anything, of course, and everything turned out well in the end. Including the sheds.

Sometimes father is pictured as a coarse man. This is hardly true. He was a strict and consistent person and always stood his ground. He was not soft, but he was kind and fair. Sometimes job cuts were declared in the institutes, and that always made father sick. The very idea hurt him. But ultimately, all people kept their jobs, and I still have no idea how he managed that. Yet he was constantly worried about these layoffs, and rushed to help selflessly. If an employee’s child got sick, he would drop everything to find the best doctors.

Once – I think it was in 1972 – Pasha’s son, Grant, got sick. I think he was a year old back then. The illness was serious, and Pasha was away – in the Moshkovo sovkhoz near Novosibirsk. He had gone there with A. O. Ruvinskiy to castrate foxes. Father called me up and said: “Pasha must return. The situation is grave, and he should be staying here. Can you cover for him?” I said: “Of course, and I have time.” I packed up and took a boat to the sovkhoz. Pasha had been notified, met me and left on the same boat. Luckily, everything turned out well for Grant. And I had a good time at the sovkhoz farm – not without use, too.

Such episodes were numerous.

The main things in life

I think that one of the most important things my father accomplished in his life was saving the Institute from closing down. Not everyone remembers that the ICG SB RAS was next door from dismissal from the very beginning for its adamant adherence to the principles of classical genetics, which was completely orthogonal to the ideas of high-ranked biological (and not only biological) executives of the time, headed by Lysenko. Khrushchev was friends with Lysenko and supported him in all ways. The Institute was an annoying eyesore for these people. Complaints, reports, audits and squelchers happened all the time.

R. I. Salganik, a well-known biochemist, was the first deputy director of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics for many years. They were not close friends with my father, yet they shared a common past: both went through the war and began to celebrate the Victory Day together in the fifties, back when we were living in downtown Novosibirsk and our apartments were in the same house. Both worked in the Institute from the start, and bore the burden of all quarrels, complaints and reports together.

R. I. Salganik, a well-known biochemist, was the first deputy director of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics for many years. They were not close friends with my father, yet they shared a common past: both went through the war and began to celebrate the Victory Day together in the fifties, back when we were living in downtown Novosibirsk and our apartments were in the same house. Both worked in the Institute from the start, and bore the burden of all quarrels, complaints and reports together.

Rudolf Iosifovich once told me: “You know, DK and I (he called father DK in that story) were different. We saw eye to eye in some things, and disagreed in other. What you should know, – he said, – is that without DK, there would be no Institute. In dealing with this crowd, he showed his outstanding intellect, his wit, his agility. Of course, many people helped the Institute, but it would be in ruins if not for DK.”

Rudolf Iosifovich told me this in 1997, during the Readings on the occasion of my father’s 80th anniversary. He had already been living in the USA but came to the Readings and gave a speech in Russian, translating it into English simultaneously. Rudolf Iosifovich passed away a few days ago. May he rest in peace…

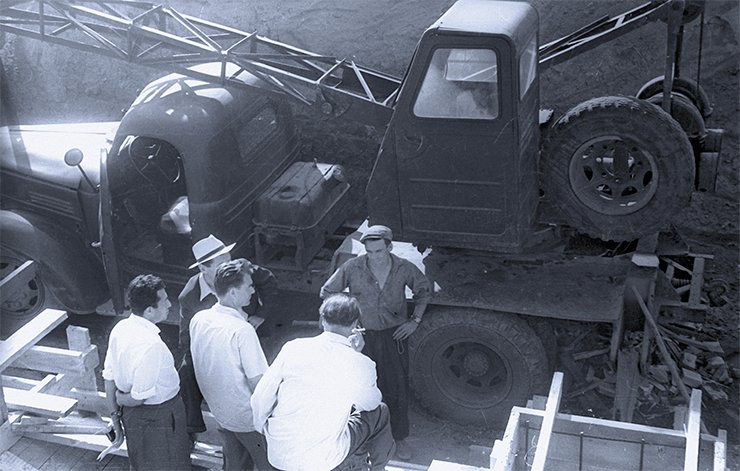

This is a good occasion to recall here how the current building of the Institute was populated in the very beginning. This story must remain in the records as the perfect example of personal responsibility. The building was erected in 1962, and before that, its various laboratories were quartered in buildings belonging to a number of other institutes: the Institute of Organic Chemistry, Institute of Catalysis, and Institute of Chemical Kinetics and Combustion. Some people stayed in downtown Novosibirsk in the building on Sovetskaya Street, 20, where it all began. Shortly before the transfer, a gossip spread that the Institute was going to be closed, and the building would be given away to another institute. Father commanded: “We are moving in tomorrow, no ifs and buts!” And they did. This is what I call taking responsibility without fear.

After the relocation, M. A. Lavrentiev summoned father and asked:

– Did you move in illegally?

– Yes I did, Mikhail Alekseevich.

– Good job! Go work now.

No matter how much I speak about Lavrentiev, it will not be enough. Father held him in immense respect and considered him a man of incredible scale. As head of the Siberian Branch of the Academy, Lavrentiev often helped my father; he fought for the Institute and defended it in the face of attacks from Khrushchev’s administration. It was Lavrentiev who pushed my father to become an Academician, although father did not see any point in that. A toast for Lavrentiev was raised on all special occasions and feasts in our home.

In 1985, father was elected the academic secretary of the Department of General Biology of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. This turn of events caught him off-guard. He said that when he went to the election he had no idea he was among the candidates. He never intended to get that position and he never worked for it. And suddenly, despite objections from his superiors and promotion of another candidate, father was nominated and elected, and it was a clear-cut victory.

The offer would be a serious career boost and would grant him direct access to many powerful officials. And I must admit that father was extremely flattered, especially because it was unexpected. But he thanked the Academy members, his colleague biologists, and declined. He explained that this position demanded long stays in Moscow, and he could not abandon his Institute for long periods. Moreover, he had plans in Siberia. The plans included the Cherga nature reserve, where he was planning to move after leaving his position as the Institute director. In one word, he turned down the position. Another person was elected.

I did not touch upon the subject of my father’s scientific research here. A lot has been written about it, but again, I stress that his work became world-famous by the effort and works of Lyudmila N. Trut. I tried, to the best of my memory and recollection, to tell about his character, his interests, and what kind of person he was. It makes me sad that father never knew, at least in some measure, the degree of recognition his scientific results would receive.

He brought glory to Russian science; there is no doubt about that. Alas, there are so few people like him left out there…

References

Hare B., Woods V. The Genius of Dogs: How Dogs Are Smarter Than You Think. Dutton Adult. 2013. 384 p.

Dmitriy Konstantinovich Belyaev: Book of memories. Novosibirsk: SB RAS. Geo Branch, 2002. 284 p. [in Russian]

The editors thank P. M. Borodin, D. B. S. (ICG SB RAS) for his help in organizing this publication

Photographs courtesy of family archive and ICG SB RAS archive