Great Northern Expedition: In the Wake of the Academic Detachment

The Second Kamchatka (Great Northern) Expedition of 1733—1743 led by Captain-Commodore Vitus Bering was one of the most grandiose enterprises in the history of world exploration: it encompassed the whole of Siberia from the Urals to the Pacific coast, the Arctic coast from the North Dvina estuary to Chukotka, coastline areas of the Arctic Ocean and northern part of the Pacific Ocean.

Numerous instructions given to the Expedition as a whole and to its separate detachments set the following tasks: a sea voyage to the shore of America; search for a sea route to the Kuril and Japanese Islands; exploration and cartographic survey of coastline regions of North and North-East Siberia; finding out whether there was a gulf between the Asian and American continents; and study of the nature, history and peoples inhabiting Siberia. Coping with these tasks was of both academic and political importance; therefore, information about the Expedition, its progress and results was secret…

The Second Kamchatka (Great Northern) Expedition of 1733—1743 led by Captain-Commodore Vitus Bering was one of the most grandiose enterprises in the history of world exploration: it encompassed the whole of Siberia from the Urals to the Pacific coast, the Arctic coast from the North Dvina estuary to Chukotka, coastline areas of the Arctic Ocean and northern part of the Pacific Ocean. The expedition was launched on the initiative of V. Bering and under the auspices of the Russian government: soon after the First Kamchatka Expedition of 1725—1730, the explorer had submitted a proposal to the Admiralty – Collegium, and an appropriate decree had been issued by Tsarina Anna on April 14, 1732. Numerous instructions given to the Expedition as a whole and to its separate detachments set the following tasks: a sea voyage to the shore of America; search for a sea route to the Kuril and Japanese Islands; exploration and cartographic survey of coastline regions of North and North-East Siberia; finding out whether there was a gulf between the Asian and American continents; and study of the nature, history and peoples inhabiting Siberia. Coping with these tasks was of both academic and political importance; therefore, information about the Expedition, its progress and results was secret. The detachments counted over 500 scientists, officers, sailors, soldiers, geodesists and other members; ancillary staff involved at specific stages amounted to several thousand.

With an aim to investigate whether it was practically possible to take the northern sea route and, also, in order to study the Arctic Ocean and Arctic coast of Asia, four detachments were formed – Dvina-Ob, Ob-Yenisei, Lena-Khatanga, and Eastern Lena – each charged with exploration of a certain area. They sailed the seas and rivers in the vessels that were tiny even by the 18th-century standards (deck boats with masts and oars, ordinary boats and oars) and traveled on land in teams of deer and dogs and on foot. As a result of dedicated work performed by the members of the northern detachments and at the price of many people’s lives, material of great volume and colossal importance was collected. Over 13,000 kilometers of the Arctic coast was described and mapped; areas of lower, and partially medium, reaches of all the large rivers from the Pechora to the Kolyma were described; considerable parts of the Kara and Laptev Seas were mapped; data on ice situation in the seas, tides, climate and population of the North and North-East were gathered. Many of the natural objects described at that time were re-investigated as late as in the 20th century. Voyages performed by the northern detachments showed the extreme complexity and grave danger of sailing along the shore of the Arctic Ocean. For instance, in the detachment led by P. Lassinius 40 people out of 53, including Lassinius himself, died from scurvy and lack of food supplies during the first winter. In the following year, V. V. Pronchishchev’s detachment suffered heavy losses because of the scurvy; the head of the detachment and his wife, the world’s first woman polar explorer, died too. Complicated ice situation made it impossible for the explorers to go round the Taimyr Peninsular by sea and to move farther than Cape Bolshoy Baranov. As a result, projects of high-latitude routes from the Russian European coast to the Pacific Ocean through the Arctic Ocean (project by M. V. Lomonosov and others) were developed; putting these projects into life became possible only in the 20th century when powerful icebreaker fleet was created.

No less dramatic was the fate of the members of the First Pacific Detachment, which sailed off to North America. It had taken about three years to start an iron-making factory in Yakutia and a rope workshop, to make the rigging and procure food and equipment. It took about the same time to move the people and cargo to Okhotsk and to build ships there. Eight years after the departure from St Petersburg on June 4, 1741 the packet ships Sviatoy Piotr (St. Peter) and Sviatoy Pavel (St. Paul), under the command of Bering and Captain Aleksei I. Chirikov, set sail. Both the ships had on board members of the Academy of Sciences: on Sviatoy Piotr, there was Adjunct G. W. Steller, who wrote a description of this voyage, and on Sviatoy Pavel, there was Professor L. Delisle de la Croyere. Separately but almost simultaneously, both the ships, which had lost sight of each other in the fog, reached the shore of America and discovered a few islands: Kayak, Kadyak, the Shumagin and Commander Islands (Komandorskiye Ostrova), Aleksander Archipelago, the chain of Aleutian Islands and some others.

The Kodsk Trinity Monastery on the right bank has two wooden churches: one is dedicated to the Life-giving Trinity and the other to Annunciation. As the former church is old, a new one, made of stone and with two altars, is being built at its site. The monastery has conventional structures such as cells, cellars, and storehouses. Outside the monastery, in three houses, live monastery servants; also, there are 15 households of landless peasants, mostly baptized Ostyaks. They have been attached to the monastery long since; the monastery can use them to do various jobs and pays for it ordinary taxes to the public purse.

(G. F. Mueller)

The tragic fate of Bering and many of his company is well known. During the return voyage, when the crew was wintering and repairing the ship on the island later given the name of Bering, Captain-Commodore and 45 out of 77 members of the Sviatoy Piotr’s crew died. Under those harsh conditions, Steller revealed the best of his qualities: he performed his duty as a doctor and carried on with the exploration. In particular, it was during that winter that he discovered, described and made sketches of the two previously unknown species: the rare animal belonging to the sea cow family (Steller cow) and spectacled common cormorant, both of which were exterminated shortly. Losses suffered by the Sviatoy Pavel’s crew were also heavy: 15 of the staff disappeared on an island of the Aleksander Archipelago, probably eaten by the Indians; another six people, astronomer Delisle de la Croyere among them, died of scurvy.

The Second Pacific Detachment led by Captain M. P. Shpanberg was charged with mapping the Kuril Islands and establishing relations with Japan. The most important result of the voyage made by the four ships of this detachment (under the command of Shpanberg, Lieutenant W. Walton, Warrant Officer A. Shelting and W. Ert) in 1738–1742 was the discovery of the route to the islands of Hokkaido and Honshu of the Japan Archipelago; on Honshu the sailors touched shore and were wholeheartedly greeted by the Japanese. Also, the entire Kuril chain was described (it was bypassed on the eastern side for the first time); the Sea of Okhotsk coast up to the La Prouse Strait and 600 kilometers of the eastern coast of Sakhalin were explored.

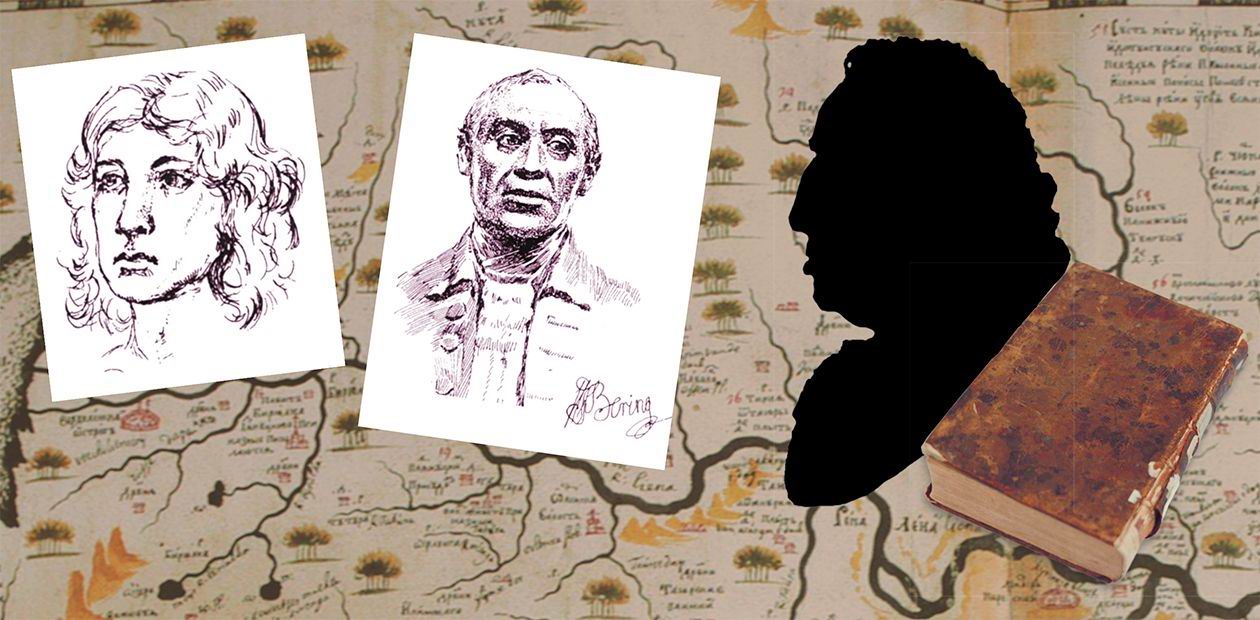

Investigation of the nature and natural riches of Siberia’s inland regions, as well as study of economy, history, and ethnography of the indigenous population was entrusted to the Academic Detachment. Its members were Professors (Academicians) of the Academy of Sciences historian G. F. Mueller, naturalist J. G. Gmelin, and astronomer Delisle de la Croyere; students P. Krasheninnikov, A. Gorlanov, V. Tretiakov, L. Ivanov, and L. Popov; translator I. Yakhontov; artists J. H. Berkgan and J. W. Lurcenius; geodesists A. Krasilnikov, N. Chekin, A. Ivanov, and M. Ushakov. Later, adjuncts G. W. Steller and J. E. Fischer, translator Ya. I. Lindenau, and artist I. K. Dekker joined the Expedition. The scholars were accompanied by workmen and workers, interpreters, and soldiers (including a drummer!). The Detachment must have looked impressive, especially at the beginning of the Expedition, when all of its members were yet there. It departed from St Petersburg in 62 carts: ten carts were due to each professor, three carts to each artist, two carts to a geodesist and translator, and one cart to a student. Though all decisions were to be made collectively, in actual fact, the Detachment was managed by the close friends Mueller and Gmelin; and Mueller was the indisputable leader because of his age, experience, and determined and authoritative nature.

The Detachment left Petersburg on August 8, 1733 and returned on February 15, 1743; some of its members stayed in Siberia until 1746—1747. Routes followed by most of the scholars covered the vast area from Southern and Middle Urals to Yakutia and Trans-Baikal region, and from the southernmost parts of Siberia to the lower reaches of the Irtysh, Ob, Yenisei rivers and middle of the Lena River. According to the estimate made by Mueller, the only member of the Expedition who had been to all the towns and uyezd’s (districts) of the Urals and Siberia, he had covered 35,000 verst’s (1 verst is 3,500 feet) in ten years.

Lack of transportation means and provisions made it impossible for most members of the Detachment to make it to Kamchatka; Krasheninnikov therefore was sent there alone; later he was joined by Steller.

From the modern viewpoint, a lot of things about this expedition seem odd. First, the time during which it was held – the reign of Czarina Anna (1730—1740) and regency of her favorite Biron – was not too favorable for such large and costly projects. Second, by the power transferred to the travelers in virtue of the Czarina’s decree, they had the right not to ask but to demand from the Siberian authorities of practically any level any information (and managed to get it) as well as procurement with transport, foodstuffs, apartments, etc. Third, the young age of the scholars who made an outstanding contribution to the Siberian studies: when they departed to Siberia, Krasheninnikov was 21, Gmelin was 23, and Mueller and Steller were both 27. Forth, it was an international team that included Russians, Germans, a Frenchman and a Swede – and the professors and adjunct were not Russian citizens.

The Detachment was led by foreigners; however, no sign of biased attitude towards Russians could be detected. Supporting this, in particular, is the fact that many notes written by Mueller and Gmelin to the Senate and Academy of Sciences contain exceptionally high evaluation of the work done by student Krasheninnikov, basing on which the professors applied for raising his salary to 200 rubles a year – to compare, a professor of the Academy of Sciences earned 600 rubles a year (1,200 rubles when on an expedition) and a Siberian aristocrat had 12-14 rubles a year. The leaders of the Detachment took the death of the talented translator and investigator Yakhontov in 1739 as a huge loss.

The scholars’ youth predetermined their ardor and passion for the unknown and even dangerous. In his account of going by water to the Upper Irtysh, Mueller noted that in the Omsk fortress another 20 Cossacks and four gunmen with four powder guns were added to the soldiers accompanying the Detachment for fear of an attack by the Kyrgyz-Kaisaks (Kazakhs). Special measures such as spending the night in the middle of the river and patrolling turned out to be redundant, and the scholar remarked in this connection: “We wished sometimes our precautions would not be in vain, but none of our enemies had appeared.” When in Zabaikaliye (Trans-Baikal region), Mueller found out from informants that on the other side of the Argun River, on the territory of China, there were remains of an ancient city, and, at his own risk, crossed the border illegally in order to examine the monument himself. No difficulty or danger could scare Steller, who behaved as though he was asking for them and experimented on himself to see whether he would manage to survive in extreme conditions.

...The Yakuts have sacred places along the roads: if there is headland extending out into a river or the road goes uphill, or there is an outstandingly tall and spectacular spruce or pine tree, every passer-by hangs something on it. It can be a small rag or a piece of an old cloth, a bit of fur or hair from his horse’s mane.

If a traveler goes on foot and has nothing to donate, he leaves his staff here. Also, a traveler should say the following words, “My babushka, here I leave a gift for you, please keep me and my horse satisfied and safe on my way”…

The scientific heritage left by the participants of the Academic Detachment is so enormous that it cannot be given due credit even now, when a great many books and articles have been written on it: thousands of pages of expedition manuscripts in Gothic cursive, with plenty of abbreviations and elements of shorthand, are yet expecting their investigators. A colossal volume of valuable information is contained in the scholars’ travel notes and diaries. They provide unique evidence on many thousand items of geography; toponyms; settlement of the Russian and aboriginal population; architecture of towns and ostrog’s (fortresses); number and ethnic composition of inhabitants of yasak volost’s (small rural districts bound to pay tribute to Russia), their history, migrations, material and spiritual culture; archaeological monuments; household duties of the Siberians; ways to communicate, etc. Many of the scholars’ descriptions are accompanied with illustrations made by the Detachment’s artists – there are plans and prospects of towns; sketches of different physical types of the indigenous peoples inhabiting Siberia, their dwellings, clothes, everyday life, and cult objects; drawings of archaeological monuments, animals, and plants. Truly unique are ethnographic descriptions not yet published, which, in the 18th century, had no rivals in terms of reliability and amount of data revealed.

...Some Yakuts regard the eagle as a deity, others worship swans or ravens. Neither shamans nor ordinary people eat eagles or ravens. Shamans do not eat swans either. Ordinary people can eat swans, but they should tie up all their bones in a bunch and put them on the roof of a shed

(by G. F. Mueller)

During the expedition local magnetic, barometric and temperature data were recorded; in some towns, meteorological stations were set up, where Russian military servants trained by the scholars kept on-going observations. Despite the imperfect equipment, Expedition members managed to determine fairly precisely the coordinates of a huge number of geographical objects, which served as cornerstones for drawing dozens of regional maps of Siberia, maps of geographic discoveries made in the Arctic and Pacific Oceans, and the so-called “general” maps drawn under Mueller’s supervision in 1745–1746 and 1754–1758. Many European scientists felt doubts about the trustworthiness of these maps and other results achieved by the Expedition. Swiss geographer S. Engel and his supporters claimed, in particular, that Mueller, in his strivings for fulfilling the political order of the Russian government, had exaggerated the harshness of the ice situation in the Arctic Ocean and that he had shifted the eastern boundary of Siberia by 30°. Neither did they believe that Bering had reached the shore of America. Mueller’s debate with the opponents, during which he, doing his best to defend Russia’s honor and prove the priority of Russian geographic discoveries, published a series of specific works in Russia and abroad, came to an end only after Captain Cook’s voyage to the Bering Strait in 1778. This journey validated conclusively the reliability of the results obtained by Russia’s scholars: according to Cook’s measurements, Siberia extended a good 4.5° beyond the longitude indicated by Mueller.

Another important line of activities carried out by the Expedition members was working out the projects aimed at the development of Siberia such as Mueller and Gmelin’s project on the organization of medical care, use of medicinal resources of Siberia, and building up a strong metallurgical industry on the basis of developing hard-coal and iron ore deposits in the Kuznetsk uyezd (the latter project was implemented in the 1930s). Also, Mueller was the author of a number of geopolitical projects. To name just a few, he developed a plan for peaceful settlement of the issue of taking in Northern Pribaikaliye (Cis-Amur region) back into Russia (implemented in the mid-19th century), and a plan of handling boundary issues in the south of West Siberia – this included development of virgin lands by Russian peasants coming from European Russia, which would grant them delivery from servitude.

The Second Kamchatka Expedition required mobilization of enormous financial, material, and human resources. The grandiose scope of this exploration effort and heroic behavior of the travelers matched the importance of the achievements. It was an essential step in developing Siberia, prerequisite and beginning of annexing and development by the Russians of North America’s western part. The history of Russian-Japanese relations dates back to this Expedition. Having become a Pacific power and one of the European countries that competed for influence in the Pacific region, Russia changed dramatically its international status. Thanks to the self-sacrifice of the members of the Academic Detachment, scientific discovery of Siberia became a fait accompli.