Description of the City of Irkutsk and Its Suburbs. "Irkutsk Customs and Life-Style"

Georg Wilhelm Steller was born on March 10, 1709 in the city of Windsheim (Franconia). When he was four years old, his father, local chorister and organist, enrolled him in the gymnasium. In 1729 he entered Wittenberg University, then in 1731 moved to Halle University. In both universities, Steller combined studies in theology and medicine, but was more interested in sciences, first of all in botany and zoology. In Halle, he started teaching at the school for orphans founded by the famous teacher and eminent pietist August Hermann Franke. The atmosphere of Halle, the recognized center of pietism, deeply influenced Steller’s fate and world outlook. Throughout his life he followed the philosophy of this protestant trend, not only advocating the ideas of rationalism, but also trying to be actively involved in practical rearrangement of the world...

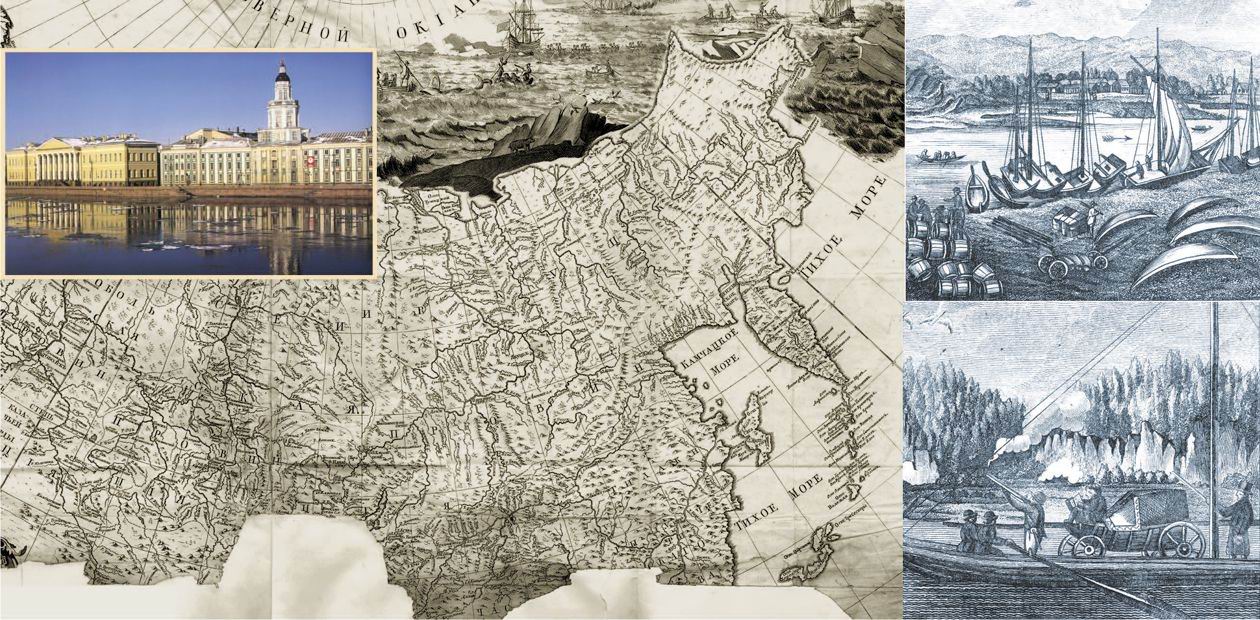

Having received a brilliant education, Steller, like many German scientists, decided to try his luck in Russia, where in 1725 the Imperial Academy of Sciences was founded. In Russia, the young scientist became the home doctor of archbishop Feofan Prokopovich, the eminent statesman and religious figure, companion-in-arms of Czar Peter the Great. Due to the support of Feofan Prokopovich and Johann Amman, Professor of botany, whom Steller assisted in compiling a herbarium for the Academy, in 1736 the young scientist was invited to the Academy as a junior scientific assistant in natural history. A year later, Steller, as a volunteer, left for Siberia to take part in the expedition of the Academy Detachment of the Second Kamchatka Expedition.

The twelve years that Steller spent in Russia were filled with adventures, hardships, and tragic events, but also with tireless studies and scientific discoveries that brought him world fame. The itinerary of his journey from Petersburg to Kamchatka (1738—40) was set through Kazan, Tobolsk, Tomsk, Yeniseisk, Irkutsk, Zabaikalie (Trans—Baikal region), Yakutsk, and Okhotsk. In 1741, Steller reached the shores of North America on the boat Sviatoy Piotr (Saint Peter) under the command of Vitus Bering. They were the first Europeans to reach Alaska (to be precise, Kadyak island near Alaska’s shore) and Steller was the first European scientist to describe it. In 1742 he returned to the continent after the tragic end of the expedition full of sore trials and continued his research at Kamchatka and on the Kuril Islands. He summed up his research results in The Description of the Land of Kamchatka (Beschreibung von dem Lande Kamtshatka, 1774), which appeared in Russian as late as in 1999 (in two independent translations simultaneously!).

For his criticism of the government actions with relation to Kamchatka’s aboriginals and his involvement in the unauthorized jail release of the Itelmens who, as he believed, had been wrongly accused of rebellion and treason, Steller was taken into custody in 1745. Although he was acquitted in Irkutsk and allowed to return to Petersburg, in the summer of 1746 he was arrested again in Solikamsk based on a warrant issued in Petersburg (the news about his acquittal had not reached the capital) and sent under escort back to Irkutsk. In October 1746, the mess was cleared up and the arrest warrant was cancelled. This information reached Steller in Tara. Having acquired his freedom, he headed for the capital, but only reached Tyumen where he died in November, 1746.

Steller’s travel diaries and a number of other expedition notes have not been published until recently and have been, hence, practically inaccessible for researchers. In the early 1990s, German, Russian, and Danish scientists undertook a joint large-scale project aimed at studying and publishing the scientific heritage of the members of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, and most importantly, that of Georg Wilhelm Steller. Many of his studies dealt with the topographic description of Lake Baikal and its surroundings; Zabaikalie; local flora, fauna and mineral resources; as well as the lifestyles of local inhabitants. His fundamental study The Irkutsk Flora is highly rated by today’s botanists. We are publishing a fragment of the Description of the City of Irkutsk and Its Surroundings (Irkutsk Customs and Life-Style)1 written by Steller during his stay in Irkutsk from spring 1739 to spring 1740. This work was recently published in German in the series Sources on the History of Siberia and Alaska from the Russian Archives. Currently a translation into Russian is being prepared for publication for a Russian-language version of the series.

Steller was a man of unusual integrity: all his works are connected as far as the fundamental ideas that interested the scientist are concerned. Upon formulating a regularity, he then sought its justifications, not forgetting to discuss exceptions to the rule.

As an example, the fragment we are offering you starts with Steller’s thoughts on the impact of natural conditions on human characters and habits. During his trip in 1740 from Irkutsk to Yakutsk Steller found much evidence that supported his idea. He had a liking for Siberian peasants and was amazed by their excellent health, firm moral principles, and diligence. All these qualities complied with the Protestant ideals he cherished. According to the traveler, the peasants from the Russian villages along the Lena River were more prosperous than those living in more favorable climatic conditions. The former had many children, were healthier, and lived longer (the scientist talked to two long-livers, 116 and 137 years old). Steller attributed this to a deeply-instilled habit for work. He was pleased to notice this habit in women and children: “In every house they make sacks of spun hemp, weave shirts, pants and sheets... One can see that because of the lack of meadows here women mow grass in the forest, like in Germany... Women and children aged 8—10 often drive carts, so that adults can do their household work and trade.” By contrast, when depicting the habits of city-dwellers, Steller became ironic (quite typical of him): “In Irkutsk, when the tea and shchi (cabbage soup) are ready, all the women sprawl out next to each other on the Russian furnace like sausages and smoke their bottoms, otherwise they would fall to pieces and rot as a result of excessive dissoluteness...”

Some years later, after he had traveled much across North-East Russia and experienced its severe climate, the researcher admitted that his general rules did not always work. Describing the local sluzhivye (government-employees) and people of Yakutsk, he wrote that they “differ from other Siberians and aboriginal Russians in their malignancy, incredible perfidy, sham, and cruelty as much as serpents differ from pigeons.” Steller attributed this to the lack of control over government-employees in remote forts and winter quarters, as well as by their social marginality. In his opinion, these were the dregs of society, “fortune hunters, fugitives from justice, or exiled here from Russia for committing offence”.

Many of Steller’s observations are surprisingly topical. This is valid not only for such obvious analogies, as the role of “new Russians” and “capitalists” (Steller’s definitions) in the development of the Siberian economy. The scientist was concerned about the birth rate reduction in the cities, moral dissipation, and the spread of venereal diseases. He worried about the inefficiency of the police whose apparatus growth paradoxically affected the increase in the number of crimes, and the undermining of public finances by the “shadow economy” (in distillation and trade), as well as about the predation of natural resources. All these concerns (and the list is far from being complete!) seem to be taken from today’s newspapers.

Steller’s biography shows that the stereotypes of a “true German scientist” do not always apply to certain personalities who have a rich individuality. Thorough education, professionalism, diligence, and traditional German accuracy in research were combined in Steller with a passionate temper, irrepressible energy, undemandingness in daily life, readiness to withstand hardships and dangers, true democratic views, and implacability towards any manifestations of injustice.

We must admit that these are the properties our time lacks. Longing for them makes us turn our glances back, to the past — and this is one of the reasons for this publication.

"IRKUTSK Customs and Life-Style"

Translation and publication by A. Ch. Elert

The name of this northern or north-eastern part of Asia, [Siberia],2 is so general and vague that it would be absurd to use it to designate all local inhabitants with all their different customs and ways of living. The varying climate partly changes and partly forces them to change their habits and traditions. The same is valid for the animals that we find here: in some places they are smarter and more eager than in others; they are more sly, as the food is scanty, and more quick-wittedness and diligence are needed to satisfy one’s appetite. All wild animals in these places, horned cattle, bears, wolves, and foxes, provide themselves with food for the winter. Particular differences are observed in dogs: the closer to the north they live and the heavier loads they carry because of the lack of horses, the cleverer they are in hunting and the better memory they have for long distance routes. On the basis of incidents concerning dogs and their local use, one could compose a thorough history of dogs that would be rather edifying because European readers still believe that certain stories about the duties of dogs in Asia are absolutely incredible.

Besides the climate [of Siberia], a lot depends upon the vicinity. Contacts with strangers and trade, which makes the people compare the quality of goods, makes them rather haughty. The Siberians themselves are aware of this; thus, inhabitants of many provincial towns or locations have been given humorous nicknames based on their main qualities. Thus, for example, the residents of Tomsk are called bulygi for their rude arrogance that was noticed by the travelers; people living in Yeniseisk are called skvozniki, that is sly; Irkutsk residents are called ivany because of their trade and considerable political pride as opposed to Tomsk residents. In such a manner there is no place in Siberia that has not been given a nickname. This proves that the local inhabitants have a distinctive life style depending on where they live: in Tobolsk, Tomsk, Yeniseisk or Irkutsk…

It is the latter that I would like to discuss in particular.

What can be observed in the history of European countries can be seen here, in Asia, namely, the more firmly people reject their old customs and ways, the more they suffer from imitating others, whereas the latter is not always caused by real necessity. Irkutsk, which dates back to the descendants of the courageous streltsy (Cossack musketeers), gradually began using German clothes, food and drink, and combined these with Chinese self-conceit.

The city is constructed near the junction of two rivers with a third one. The first river [Angara] flows out of a large lake [Baikal], the second [Irkut] comes here from virgin mountainous places, and the third [Ushakovka], which hardly deserves mentioning, received its name from the surname of a miller who lived here. The origin and development of this settlement is best characterized by the fact that it was founded by the Cossacks as a place for wintering, which later grew into a village. It has become a town thanks to the efforts of the convicts exiled here in a great hurry from Moscow and other places of Russia. Buryats, as the indigenous people, hardly deserve special attention; there are very few of them, and they live in yurts outside the city.

Thus, the city hosts three categories of inhabitants: Siberians, exiled or “new Russians”, and Buryats. Promyshlennye, or traders involved in trade, craft, and mining, can also be considered as inhabitants. They have come from the poorest places in Russia to become richer than they were previously; many of them have stayed here for good. There are not many old-time Yenisei and Krasnoyarsk cossacks here now, probably because almost all of them have left for the stockaded towns, Barguzin and Idin around Lake Baikal, and further on when the city expanded. They left because the great number of convicts in these places meant they were no longer needed as guards. There are only few families of Russian merchants who moved here on their own free will, such as the Milutins and the Brechalovs. The majority of merchants descend from convicts. Today they are wealthy people and not in the least are they rebellious. Moreover, they blush when they hear the word streltsy. They make up the trading quarter, posad, together with the Cossacks, or as they are now called, they are the soliders, or sluzhivye, employed by the government for military and civil service. However, they prefer to be occupied so that they have a chance of being engaged in commerce and making profit. These sluzhivye are paid a salary in cash from the State Treasury and are given provisions, but sometimes this is arranged otherwise.

Some of them do not get the salary or provisions but pay themselves to have the right to be appointed for collecting yasak (the tribute) or be sent with the money to Russia, because in this case they would get extra income from trade. The poorest receive money and provisions and are appointed to the hardest work. Today, for example, they are assigned to Okhotsk and Kamchatka as bonded laborers and carpenters. Others get a parcel of land from the Chancellery to construct winter camps, houses, and farms there; they ranch much cattle, raise crops, trade with Buryats and feel quite comfortable. Dealers also get lots from the Treasury to build houses and farms. In time these buildings grow into villages and eventually slobody (the outskirts of towns). The majority of Irkutsk outskirts were formed in this way. The money for the land is paid to the Treasury immediately.

The traders, or promyshlennye, originate from all cities of Russia and Siberia, but most of them arrived from the Arkhangelsk province and the cities of Ustug, Vologda, Sol’ Vychegodskaya, Yarensk, as well as from Arzamas, Yaroslavl, and Ryazan, after trade in Arkhangelsk stopped. In Russia, they are called barge haulers or idlers. Here they are called traders, or promyshlennye, and they do whatever they wish, while earlier this word was used only for those who were engaged in the fur trade of sable, fox, beaver, and polar fox, fishery or supplying mica and similar goods to merchants. The traders can be divided into two groups. Some come here at their own will to earn some money and then go back to Russia, buy real property there, and live as decent people should. These are government workers, tax-paying townsmen and peasants, or various kinds of craftsmen. They obtain passports for three to six years in the chancelleries of their native places. In all cities, the passports are signed by the voyevodas (military governors) who provide references for the passport holders. They arrive here mainly with the merchants who employ them as workers on their boats. Or they work somewhere, start trading, move from one place to another, and thus finally reach these places. In Irkutsk or other cities, they hand over the passports to the Chancellery for their signature, and then the townsmen submit them to the Ratusha (from German Rathaus)3. Upon settling here they get involved in various business activities.

Some of the traders fish from board boats on Lake Baikal, in particular, at the mouth of the Barguzin River, on the Chivyrkui River 50 versts away from Barguzin, and on the Upper Angara River. However, today nobody dares to go to the Upper Angara because local Tunguses take away the fish from the traders more boldly than elsewhere, even killing the fishermen in case of resistance; this has happened more than once.

Starting their business, 14—15 traders gather to agree on the arrangements, and pool their money together, usually each giving about 50 rubles. They buy a board boat, a side sail, a mast and cordage, which, together with the sweep-net, (a fishing net from 130 to 150 cubic sazhens4 long), costs about 500 rubles. Then they visit the Chancellery and humbly request a decree, so that the salesclerks will not hinder them. The decree states that the trade is duly registered in the Ratusha and indicates that seven rubles was paid for the sweep-net. Then the Chancellery informs the Customs about the place assigned for fishing because,when they return, the traders show the fish at the customs post, which checks that they do not import any goods under the guise of fish. Then they pay the tithe to the customs office, one tenth of the price established by the tseloval’nik (tax-collector). When the traders settle all the problems, they buy salt, provisions, meat, and various utensils and go upstream on the Angara River to Lake Baikal on St. Nicholas day. They take barrels as staves, which they knock together near the estuary. There they build a winter camp, a Russian steam bath, a shed in which they salt fish and repair the sweep-net, and a frame for drying the sweep-net. The board boat is anchored, while they fish in two smaller boats.

The crew includes the following members.

The foreman does not contribute any money and is senior among them. He knows the way to the lake, warns about the dangers, and determines the places for halting and the places suitable for fishing. The foreman should be experienced in drawing and boating a sweep-net, as well as in repairing it. Along with these duties he makes the order when it is time to go fishing.

There is also a cooper. Throughout the winter he makes barrels; then he knocks them together. He does not contribute any money, but gets only half share of the revenue. The other half is paid to a cook who, by the time fixed and in the order prescribed, brews kvass, bakes bread, butchers cattle and salts meat, delivers salt, serves meals, and attends the crew. He does not contribute any money either and is not involved in common work.

The remaining eleven crewmembers, each of whom has contributed fifty rubles of his own money, are split into several groups, so that several persons can in turn take the helm when they are on the lake. The foreman gives the orders “Port!” and “Starboard!” from the prow. When on land, they all work together. The crew members get along well with one another, voluntarily settle all quarrels, are friendly and considerate. Before meals they pray reverentially. While eating they never talk; it is as silent there as in the dining hall of the orphanage in Halle. After meals the crewmembers pray again and return to work. Reckless workers are not admitted to the crew or are driven out, because, as they say, disorder can annoy the deity of the lake. The crew has plenty of good food. They enjoy being their own masters, when nobody governs them.

In late August, the boats come back loaded with sturgeon, whitefish, and omuls. The traders always fish for sturgeon. To this end they go to the Chivirkui River, and then in mid-August there begins the season for omul. When sturgeon was very abundant, the fishermen did not take other fish. But now sturgeon is so rare that they thank God for omul. In the old days they caught sixty barrels of sturgeon in one haul near Olkhon Island; now before the omul season the whole crew hardly gets seven full barrels. They catch whitefish as well, and when it is omul season they catch 10—13 barrels in one fishing. Then in early September, the traders return to Irkutsk with seven barrels of sturgeon, 25 barrels of white-fish and 100 barrels of omul on board. One barrel stores from 1,000 to 1,100 omuls. A barrel of omul costs on the average three rubles, or at least one and a half rubles. A barrel of whitefish costs seven rubles, at least five rubles. A barrel of sturgeon costs seventeen rubles, the lowest price being thirteen rubles. The total is 594 rubles, which is 42 rubles per person.

In the winter the crewmembers live in the winter camp, and though their life is not as ample as during the fishing season, they do not suffer need. Since they live together, the food costs each of them no more than five rubles for nine months. Their life becomes slightly more difficult if their board boats are taken for the Czar’s service as carriers for provisions and are driven from one fair to another. The crew members themselves are often sent to do unpaid labor; however, they tolerate this with greatest obedience, at least, during the war5 and as long as the decree on their return to Russia is valid.

In former times after the sweep-net money had been deposited, fishing was free near the Selenga River, at Prorva near the Posolsky monastery, near Barguzin, the Chivirkui, around the Olkhon gates and elsewhere around Baikal. But now a decree of the Irkutsk Province Chancellery bans to fish the selenga omul. This measure was taken upon the request of Master Brigadier Buchholz from Selenginsk who justified it by the fact that the fish near the Selenga estuary is partly caught and partly frightened away, and does not go up the Selenga, and thus the local people are deprived of fish and undergo hardships. The Posolsky monastery drove out traders from the Prorva and secured fishing there exclusively for itself. As for Olkhon, the traders left it on their own because the sturgeon from there moved the Selenga several years ago.

In the winter some traders do the jobs they are skilled in for monasteries or do short-term jobs for peasants.

Seal fishery, the second important trade, will be described in detail below.

Concerning the third important trade, the fur trade, including the sable fur trade, it was thoroughly described by Doctor Gmelin.

The fourth important trade is mica mining, upstream of the Vitim. All details of Chancellery procedures are similar to the fishery.

Some traders are engaged in selling various goods on their own or as salesmen of merchants; thus, many merchants who are now rich have become wealthy in this very manner.

Others mine iron and heat it, paying the tithe to the Treasury, as for example, in Kamenka downstream on the Angara, and before that in Ushakovka, Bugul’deikha, and Anga. The latest mines are now built as factories and belong to Afanasii Dementiev and Lanin.

Those who cannot live on commerce and are employed by peasants usually earn 20—24 rubles per year in addition to meals.

There are also those who winter along the uninhabited roads, for example along the roads to Yeniseisk and Lena, who brew beer, stack hay, raise wheat, and keep salted fish.

Some traders work at kashtak6 of Her Majesty as lumbermen and distillers.

Almost all craftsmen in Irkutsk are from these traders. Sometimes one can hardly determine if the castings, smithery, embossing, and graving on gold or silver were made in Moscow or Irkutsk. They even manufacture mathematical tools (quadrants, astrolabes, and bow compasses); they are so skillful that one might think that the tools were produced in England and not by Russians in Siberia. Gravers, wood turners, blacksmiths and silversmiths, engravers on horn and bones, copper smelters, wire drawers, button-makers (making buttons of gold, silver, as well as silk, the latter is considered to be women’s work), smiths, locksmiths, and whitesmiths mainly come from among the traders. A cloth factory with dye-works is located near the Belaya River in Telma and Irkutsk. The above list can be supplemented by tailors who compare well in their skills with their Petersburg colleagues, as well as by shoe-makers, embroiderers, artists, sculptors who carve and ornament beautiful French decorations on the buildings, saddle- makers, needle-makers, and wig makers (barbers) that appeared here not long ago. Furthermore, there are knife-makers, copper-smiths, tin-smiths, comb-makers, and weavers of tafetta and kamka7 cloth.

However, one should admit that among the traders there are many who neither want to be an apprentice to a craftsman nor to work, because earlier, while they lived on the Volga, they acquired a taste for stealing and murder. Then they moved to Siberia, where they live without passports and significantly reduce the safety of Siberian cities which is so praised. They are homeless and try to conceal themselves to avoid passport checks, which frighten them because their passports have either expired or are nonexisting. However, the current strict investigations and decrees on the examination of passports give grounds to believe that these weeds will be rooted out soon.

Summarizing the traits typical of the traders, one should emphasize the following:

1. They are very diligent; with great pleasure we observed how they work with skill and vigor, three times faster than the lazy native Siberians.

2. The traders have a high opinion of themselves and their skills, which is supported by the fact that local goods are twice as expensive as those produced in Moscow.

3. They maintain, supply, and protect Irkutsk, because they are fishermen, peasants, and craftsmen. At first summons they become good soldiers and to this day they make up the local Russian garrison.

4. The traders bring harm to Irkutsk morals, because they cannot get married; this leads to a general spread of debauchery and an increase in syphilis.

(G. W. Steller, S. Krasheninnikov, J. E. Fischer. Reisetagebucher 1735 bis 1743. Halle, 2000, p. 28–36).

1The fragment is slightly abridged; however, the abridgements are not marked in the text, since they do not distort the logical narration (Editor)

2Explanations in square brackets and comments are provided by the translator (Editor)

3Ratusha is a Town Hall, the seat of municipal authority (Editor)

4Russian sazhen is a bit more than two meters (Editor)

5The war against Turkey that Russia waged in 1735–39 in coalition with Austria to get an outlet to the Black Sea (Editor)

6Kashtak is a small distillery (Editor)

7Kamka is Chinese pattern silks (Editor)