Let Him Be Gray-Headed!

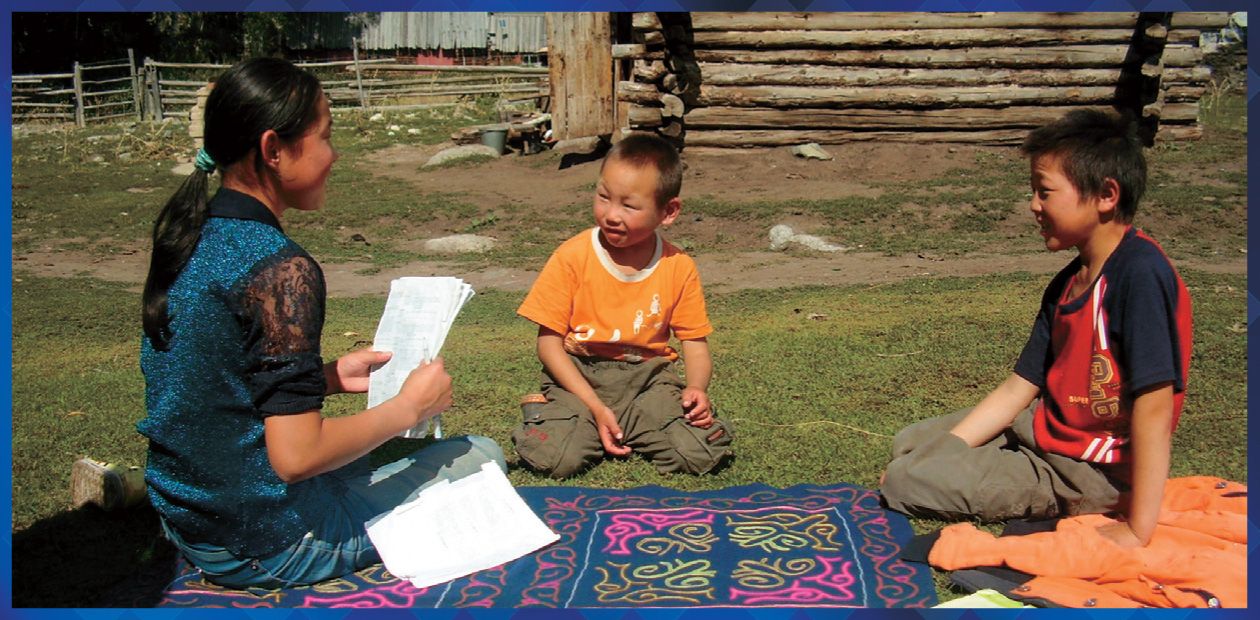

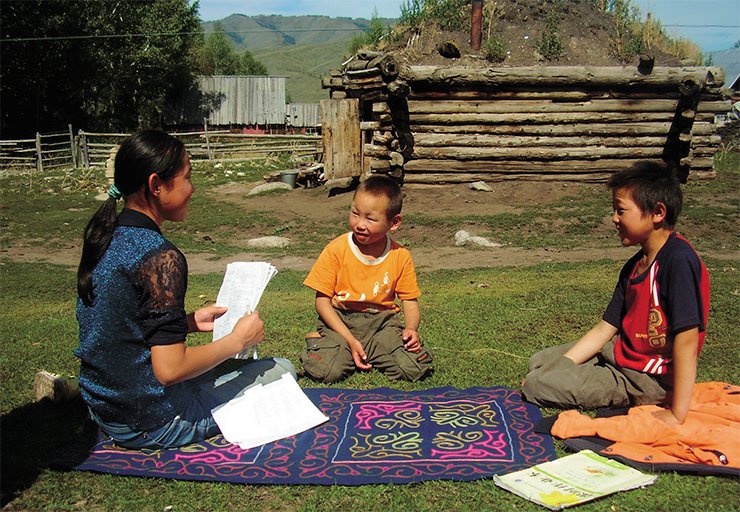

Childhood in the modern culture of Chinese Tuvinians

The Tuvinians—a small indigenous group of Central Asia—today live in three countries: Russia, Mongolia and China. Most Tuvinians live in the Tuva Republic, Russian Federation—in 2010 their number was 250,000. The ethnic groups of Tuvinians settled in China and Mongolia are considered ethnic minorities and have no nationality-based territorial formations of their own.

The Tuvinians of China is a small ethnic group living compactly in the Altai Aimag (province), Il-Kazakh Oblast, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. According to their own estimate, there are about 2,500 of them now. This paper presents the results of the author’s studies performed in 2010–2014 in the places of residence of the Chinese Tuvinians

In recent years, thanks to a rise in the living standards and medical service and strengthening of control over demographic processes in China, all Tuvinian women deliver in maternity clinics instead of resorting to domiciliary obstetrics. Despite this, the Tuvinians of China continue to hold in highest regard the traditional rituals assisting mother and child’s health and welfare. Contributing to this is the practice, still existing in China, of giving to a Tuvinian mother, on her release from the maternity clinic, the placenta of the newly born baby, packed in a special bag. Therefore, in contrast to the Tuvinians of Russia, the maternity cycle of the Chinese Tuvinians still includes the customs connected with the afterbirth and navel-string, which never used to be discarded but were kept in a special place.

The large system of rituals pertaining to childhood, which has preserved a lot of archaic features, is intended, firstly, to protect children against evil eye and evil spirit. Secondly, these rituals should contribute to the children gaining health and becoming sound family and clan members. Therefore, the rituals of the children’s cycle are invariably accompanied by magic acts; they focus on the future.

Placenta burial

A special place among the birth rituals of the Chinese Tuvinians belongs to the acts performed with the placenta. According to tradition, the placenta, delivered after the baby, should be buried inside the home (the teepee) or in the yard, where nobody will “step on it.” This ritual, which remains obligatory, used to be performed on the third day after a baby was born. Today, they go through the placenta burial ritual (songu iesin shygzhaary) on the day following the mother’s coming back home from the hospital. The well-known ethnologist A.K. Baiburin , who studies East-Slavonic ceremonies, notes that placenta burial “is necessary for providing a new birth, preserving the relations of the continuous exchange between ancestors and descendants, non-people and people, life and death” (1993, p. 43).

China’s modern demographic policy Since 1980, China has implemented the sweeping demographic policy “One family – one child.” Today, the exception is Chinese families living in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, who are allowed to have two children. This is attributed to the Uygur issue of Eastern Turkestan separation, which is topical in Xinjiang. Therefore, the Chinese government intentionally populated this territory with the titular ethnic group, the Han. National minorities, making up 2% of the country’s population, also enjoy a sort of privilege. Mothers employed in the public service are allowed to have two children, and housekeepers, three. In the event a working woman decides to have a third child in lawful matrimony, the family will have to pay to the state a fine of at least 5,000 yuan. The authorities conduct the policy against having many children by granting annual allowances to families, thus encouraging them not to have a third child. Township administrations have a special worker whose mission is agitation and handing out free means of contraception.

National minorities, making up 2% of the country’s population, also enjoy a sort of privilege. Mothers employed in the public service are allowed to have two children, and housekeepers, three. In the event a working woman decides to have a third child in lawful matrimony, the family will have to pay to the state a fine of at least 5,000 yuan. The authorities conduct the policy against having many children by granting annual allowances to families, thus encouraging them not to have a third child. Township administrations have a special worker whose mission is agitation and handing out free means of contraception.

Because of the demographic situation, China pursues a hard-line family and marriage policy. Couples who are not legally married cannot live together, there is no such thing as civil marriage, and women cannot have babies out of wedlock. If social workers detect pregnant women who are not married, their pregnancy is terminated.

According to Chinese scientists, the implementation of the demographic policy “One family – one child” has both strengths and weaknesses. On the one hand, having organized efficient control over births at various levels, the Chinese government has managed to decrease the growth of the population by several million people in the last 35 years. On the other hand, the Chinese nation has now to face urgent issues connected with planning and having children.

Since a family can have only one child, many parents, who thanks to modern medicine can find out the sex of the future child, refuse to have a girl. Because of that, doctors are now forbidden to give the parents information about the baby’s sex. Chinese families traditionally prefer boys, who are considered to be transmitters of life and family while girls are treated as temporary members of the family. As a result, according to statistics, the number of men is much higher than the number of women, which entails some problems with family and marriage. Another problem topical for China, as well as for many European countries, is aging of the population.

On March 20, 2014, the Third Plenum of the Eighteenth Central Committee of the Communist Party of China officially announced a policy allowing to have a second child in the event one of the parents was the only child in the family. Subsequently, detailed rules for the implementation of this policy were published in various places around China. This important action, introduced by the new Chinese administration, takes into account the national demographic situation, level of social development and the wish of the people. “However, a year has passed since the policy was implemented, and there are no signs of the expected second-child boom yet” (Chun, 2014).

To perform this ritual, the baby’s parents choose, among their friends or relations, an “umbilical mother” (kindik avasy), who conducts the rituals and who will cater for the child in the future. This demonstrates how the institute of Tuvinian midwives has changed with time—assisting a woman in childbirth and performing the placenta burial ritual used to be a midwife’s primary duty. Today, her role is less important: she only takes part in the placenta burial ritual, which requires no professional skills. At the same time, the “umbilical mother” has to be a most deserving woman, who herself has healthy children. To this day, the custom of honoring the midwife is observed: the child’s parents invite her as a respected guest to family celebrations and give her expensive presents.

The placenta burial ritual involving the “umbilical mother” is conducted at home, in the morning hours, in a narrow family circle—strangers are not supposed to see how the ritual is performed. Males, except for close relatives, are not allowed. The pit for placenta burial is dug in the home or outdoors. For fear that a dog may dig up this place, most families perform the ritual at home; if it is performed outdoors, a place protected from rain and snow is chosen.

Prior to the beginning the ritual, a new mother is treated to mutton broth, cooked especially for the case. Traditional medicine believes that it helps mothers to restore their physical strength and recover after childbirth. According to the mythological beliefs of Chinese Tuvinians, a new mother is “unclean,” so she shouldn’t touch any sacred objects or do household chores.

To perform the ritual, a shallow round pit is dug and its bottom is lined with white felt. The placenta is wrapped in a new white fabric and placed in the pit, on the felt. Then, a sacrificial fire of juniper wood (artyshtyg san kaar) is made above the pit.

The new mother is taken to the pit; her face, hands, chest and feet are washed with boiled juniper water. The midwife whispers the spell for three times to ward off ailments from the new mother: “Azhyg dolgaanny bodun al, achy-buyanny ber!” (Take away rough luck and give her your blessing!). The ritual sayings may differ but their aim is to make sure that the new mother gets rid of pain and complications. After the mother is wetted, alastaar—fumigation with burning juniper—is performed at the same place, three times cum sole (evidently, this ritual act can be traced back to purification with fire). After the mother, the baby, too, is brought closer to the pit to be fumed with juniper. All these acts are intended to protect the mother and the child from malign forces and diseases.

To complete the ritual, a few sacred objects are put into the pit in a certain order. First, the midwife pours in a bowl of meat broth; then goes a cooked mutton shin with a ritual ribbon tied to it, all wrapped in clean fabric. The shin (choda) deserves a special mention: Tuvinians use it as ritual food in three basic ceremonies: births, weddings and funerals.

Some other things can be put into the pit as well. If the newborn is a boy, it is a small willow saadak (an arrow and a bow) to make sure that the boy becomes a hunter and a marksman. For a girl, it is a mirror and a comb so that she grows up pretty and neat. Some families, however, put a saadak for a girl too to safeguard her against malign forces. An interesting detail: before the bow is put in the pit, they shoot an arrow into the pit three times ; after that, the arrow is placed on top of the bow so that it is on full combat alert.

On the completion of the ritual, the pit is covered with a stone and millet is strewn on top of it, which symbolizes prolific progeny. Then the midwife makes a good wish to the child and fills up the pit:

Let him be grey-headed,

Let him be long-living,

Let him be a strong young man,

Let him be a great scientist!

According to Tuvinian traditional beliefs, the performance of this ritual has several aims: it guards the new mother from illnesses and cleanses her of wickedness, protects the baby and provides future fertility.

Feast in honor of a birth

Having performed the ritual, in the afternoon of this very day, the husband’s parents or relatives organize a feast to honor the child’s birth (kalcha doi), where only old and married young women are invited. According to traditional beliefs, this is the first doi-feast for the newborn baby, which marks the beginning of a human’s life. The new mother does not participate: she and the baby are in a separate room since they cannot be admitted to the people’s world yet. As anything new and fragile, they are both too weak and have no protection against evil forces.

The midwife, who had assisted the mother in childbirth, used to be given presents: kurdyuk (sheep’s tail fat), clothes, and alcoholic drinks. Today, the “umbilical mother” gets gold earrings and a ring in acknowledgement of her help.

The feast lasts until late at night, with some guests arriving and others leaving. During the feast, the guests who have arrived must make a good wish (algysh) in honor of the child. Some ritual action, having the meaning of well-being, is performed: the person making a good wish should hold a ritual bowl in his/her hand with the best pieces of meat and pass it in a circle from hand to hand. The aim of algysh is well-wishing, giving advice and instructions for the future. For example, they wish the baby to become a famous scholar so that he will bring fame to its parents:

So that the names of father and mother will be uttered with respect,

So that he will become a great scholar,

So that he will be a rider of a big horse -

Let this road open to him!

The good wish addressed to a girl mentions not only needlework but also her future education:

Let her right hand be deft and beautiful!

Let the ten fingers be educated!

Wishing the child to live long, the well-wisher metaphorically points out the marks of longevity so that the baby will live to an old age:

Let him have endless prosperity!

Let him be long-living!

Let him have a steady destiny!

Let him be grey-headed!

Following a pronounced good wish, all the participants of the feast used to say in chorus the traditional phrases: “Let him be the god’s mandate!”, “Let it be!”, “Let this wish come true!”, thus showing approval and involvement in the event.

In the old times, aged and respected people used to give the name to the baby (at kaar) during the feast because it was believed that choosing a “happy name” was of great importance for the baby’s future life. Chinese Tuvinians used to give their children two names: the true name and home name (og ady, bichii at).

The home name was intended for the family members only. Examples of these names are Tarangai (Bald-head) and Bagai-ool (Bad Boy). It was done to protect the child against evil eye and the works of evil spirits. If in a family children died in infancy, the parents could give a girl’s name to a boy and boy’s name to a girl, with a view to deceiving evil spirits. They told us about an old man who had the female name Saryg-kys (Fair Girl).

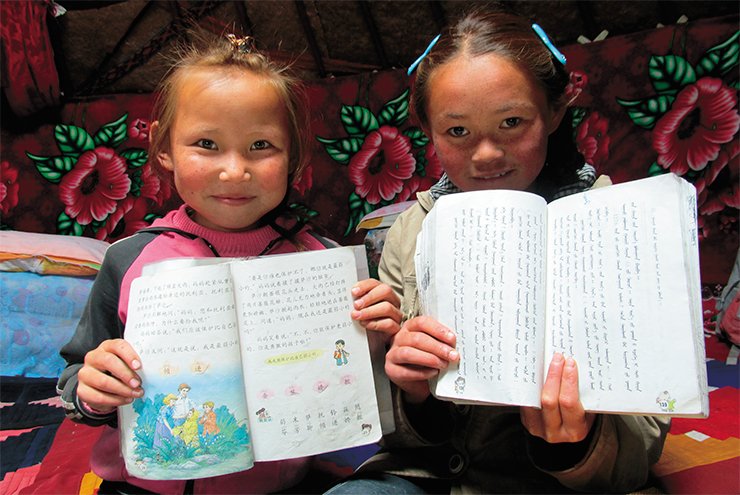

Children used to be called by their home names until they were three: by this age, it was thought, the child has survived the most dangerous period of his/her life. Today, the Tuvinians of China usually give their children names with a good meaning, and many parents ask Buddhist lamas to give a name to their child (as a rule, Tibetan or Mongolian).

The first shirt and the first cut

Seven days after the birth, the “umbilical mother” hands in to the baby’s mother a new shirt with a cutout front, saying “The first shirt for a baby who has come to this world.” This shirt is called kir koilee (dirty shirt), which is probably intended to protect the child against the works of evil spirits. On this very day, a small feast is prepared dedicated to putting the baby in a cradle.

To do this, kin avasy or a woman advanced in years first fumigates the cradle with juniper, and then puts the baby in it. Every participant shall put on the top of the cradle a diaper he/she has brought and make a good wish to the baby:

Grey-headed,

With wobbly teeth,

Long-living,

With a steady destiny let him be!

Often they put “amulets” in the cradle, which is aimed at warding off evil: scissors for a girl and a knife for a boy.

By the way, Chinese Tuvinians still take precautions having protective functions. For example, they try not to take little children outdoors after sunset. If this is necessary, a child’s forehead is covered with soot so that evil spirits cannot see him. In addition, adults perform imitative action, saying “The child did not go out, a grey hare went out.” Besides, they never leave children’s clothes outdoors after sunset because at this time malign forces become more active.

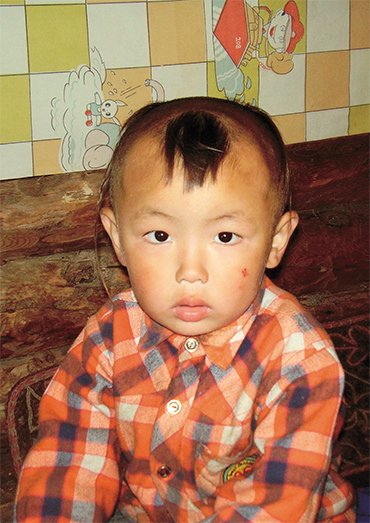

An important ritual of the children’s cycle is hair cutting. When a child is a year, three years or five years old, the parents do his hair (tulum), leaving intrauterine hair on the forehead and temples. Children wear this hairdo until the ritual of the first haircut, which symbolizes the end of the infancy period. According to the Tuvinians’ beliefs, now malign forces can no longer do harm to the baby since his/her life force (kut) has strengthened.

The ceremony of the first haircut is a family holiday. The child’s parents invite all their relatives, friends, and, of course, the midwife. Men are also allowed to join.

Prior to the ceremony, a white cloth is tied to the scissors, which are then fumed with juniper. The first person to do the haircut is the maternal uncle, followed by esteemed people of venerable age. Guests usually give living creatures or money as presents. Cutting a strand of the child’s hair, each person participating in the ceremony makes a good wish, which not only predestinates the child’s happy future but also gives guidance:

Let him have a bale if he stays out overnight!

Let his spiritual strength grow!

Let his well-being multiply!

Let him have knowledge to go to university!

The cut strands of the child’s hair are treated as a “treasure”; they are put in a bowl to be gathered in a bundle, then put in a bag and needled. For some time, Tuvinian children wear these bags on their clothes, and then parents put them away in a coffer. If a child loses his/her bag, this is not deplored.

The performance of the first cut ritual depends of a family’s well-being. On rare occasions when the family cannot afford the material costs necessary to organize the feast, the baby’s parents ask the mother’s uncle to cut strands of hair, which implies that the hair cutting ritual has been performed according to national tradition.

Summing up, we can state that the traditional rituals of the children’s cycle of the Chinese Tuvinians have not undergone any radical changes in the modern context: their ritual culture is alive and well. An important role in the structure of the performed rituals of the children’s cycle belongs to various cultural codes that implement the main idea of the rituals: modeling a child’s walk in life and good fortune.

It should be noted, at the same time, that the original culture of the Chinese Tuvinians living in a different ethnic environment undergoes gradual transformation; there appear borrowings of singular rituals and traditions. For instance, urban Tuvinians, as well as local Chinese, have lately begun to practice the Muslim ritual sundet (circumcision) for boys.

References

Baiburin A.K. Ritual v traditsionnoi kul’ture. Strukturno-semanticheskii analiz vostochno-slavyanskikh obryadov (Ritual in the Traditional Culture. Structural and Semantic Analysis of the East Slavic Rites). St. Petersburg. 1993. P. 43 [in Russian].

Mongush M.V. Tuvintsy v Kitae (istoriko-etnograficheskii ocherk) (Tuvinians in China (Historical and Ethnographic Review). Kyzyl, 1997. P. 5 [in Russian].

Tu Ya. Rozhat’ ili ne rozhat’? // Kitai. 2014. N 12(110). P. 31 [in Russian].

Chun Ya. Povyshennyi indeks schast’ya // Kitai. 2014. N 12(110). P. 29 [in Russian].

Yusha Zh.M. Zarubezhnye tuvintsi v ob’’ektive fotokamery. Tuvintsy Kitaya (Foreign Tuvinians in the Lens of the Camera. Chinese Tuvinians). Folklore and Ethnography Photoalbum. Novosibirsk, 2014 [in Russian].

The photos are the courtesy of the author