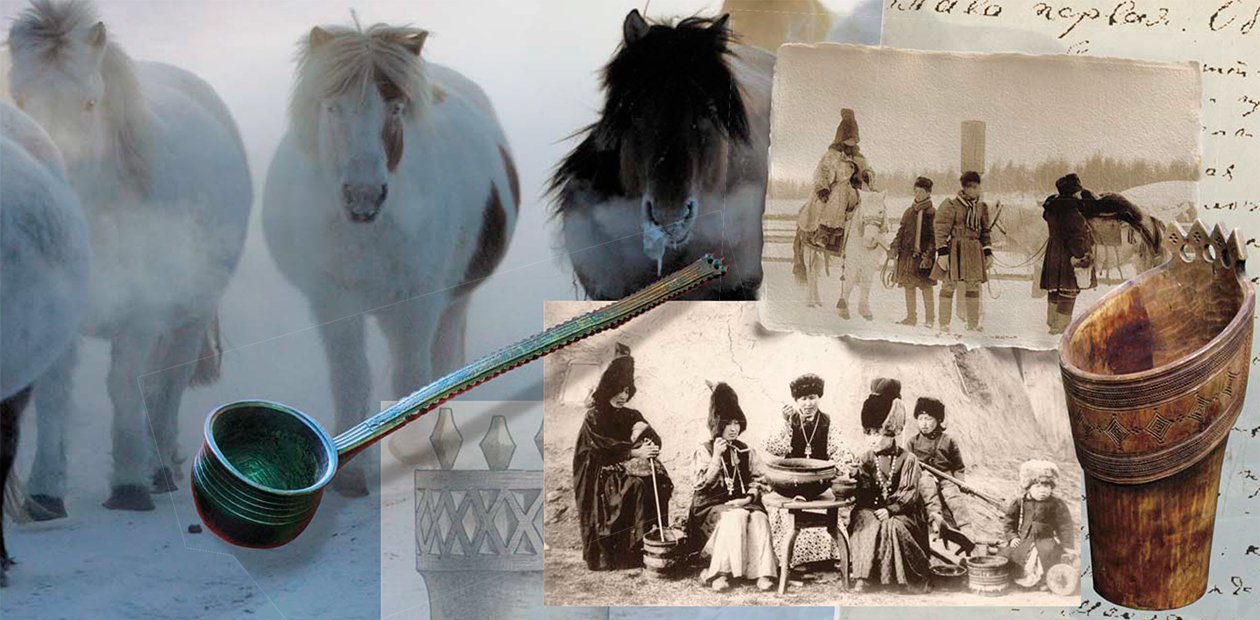

Food without "Soul" Does Not Fill. Social and Ritual Aspects of Yakuts' Traditional Diet

"Food occupies a highly important place in Yakut beliefs, mainly in what concerns sacrifice offerings and "negative" taboo magic. According to Yakuts' beliefs, food (similarly to any other object) has a soul of its own, which is its quintessence, or vital principle, concluded in a material body. In part, it is this belief that underlies the theory of food sacrificing. For example, they used to put dishes with various meals and drinks in front of a god's image; the offerings were later given to old people, who had to do with food without "soul." " This is an extract from the monograph of Yakut ethnographer A.A. Savvin (1896-1951), devoted to Yakuts' traditional nutrition system. It was published first fifty years after author's death.

In this publication we are turning to the unique materials concerned with the spiritual aspects of this northern people's traditional diet. They were collected by the scholar during many years of field research at the time when some of the customs and rituals described were not an ethnographic rarity but a part of everyday life. Ethnographic approach to food studies allowed A. A. Savvin, as early as in the first half of the 20th century, to near the understanding of the food's important role as a universal adaptive cultural mechanism

For the Yakuts, similarly to other kindred nationalities, hospitality was a common national practice. As a rule, people would pay long visits to other uluses without taking any provisions. Thanks to the national tradition of hospitality towards travelers, one would often stay the night with total strangers. Those who visited the Yakut land noted that a traveler making a journey across the Yakut deserts would find in any home warm hospitality and readiness to share with him everything the hosts possessed

We are offering our readers another publication based on the fragments of A. A. Savvin’s monograph Yakuts’ Food prior to the Development of Crop Growing (an experience of a historical-ethnographic monograph) (Yakutsk, IGI ANRS(Ya), 2005).This book was issued half a century after its author was dead. Moreover, only one small article out of Savvin’s enormous heritage was published during his lifetime.

Why did it happen? Savvin was a self-educated scholar from the family of a peasant of average means, who later went broke. His formal education amounted to two years at a non-classical secondary school. He worked as a clerk at the municipal council, judge assistant, bookkeeper, and a village teacher. What attracted him more and more, however, was the study of his people’s ethnography and folklore, and he decided to dedicate his further life to it.

He became an employee of the Yakutsk Institute of Language, Literature and History when he was over forty. At first, he was even expelled from the institute because of “insufficient education,” and more than half of the time he spent on scientific work he was not a staff member.

Nevertheless, the results of his academic activities speak for themselves: Savvin collected a wealth of field data on a variety of aspects of Yakut culture: archaeology, ethnography, folklore, beliefs, language, folk medicine, and meteorology. Today, all these materials are kept in the Archive of the Yakutsk Scientific Center.

The monograph devoted to Yakuts’ traditional nutrition system was published thanks to the efforts of researchers from the Institute of Humanistic Studies, Academy of Sciences of the Sakha Republic (Yakutia), who had done an immense preparatory work (the monograph’s editor is Doctor of History Ye. N. Romanova).

We have already published the chapter concerned with dairy products, which are the most important part of Yakut traditional diet, well balanced and featuring a good ratio of all the elements necessary for the body’s normal metabolism (see SCIENCE First Hand (in Engl.), 2006. # 1 (6). P. 96—105).

In this publication we are turning to the unique materials concerned with the spiritual aspects of this northern people’s traditional diet. They were collected by the scholar during many years of field research at the time when some of the customs and rituals described were not an ethnographic rarity but a part of everyday life.

In Yakutia, well-to-do and hospitable families were never short of guests, whereas the poor did not have many visitors. A great many people would stay with local citizens during public meetings and at the time of fishing with sweep-nets. Even not so well-to-do people would have 10—15 guests staying for the night and provide food for them. The richest would often put up 20—30 people: some of them were friends, some were relatives, and others came on business. Sometimes these were strangers going to a nasleg or ulus, or officials traveling on work

When the Lena mines opened, and so commodity economy and money turnover emerged, there were a lot of rich Yakuts who sought obtaining a credit or habal, a settlement of debt obligations. Having come on business, they enjoyed the rights of guests and would sometimes stay the night with the creditor himself.

All the visitors including total strangers enjoyed the rights of guests and stayed the night free. Generally, paying for the meals and for staying overnight was out of the question as it contradicted the national practice of hospitality. The only exception would be the poor living next to busy roads, whose yurts were a kind of inns. To an extent, they were dependent on the charity of the travelers, who would give them meat, butter, and other products in exchange for staying the night and getting food for their horses.

Gatecrashers

The Yakut custom of hospitality was a mixed blessing though. Taking advantage of this unrestricted cordiality, some people would abuse the old custom and practice frequent visits to their neighbors. Even not very well-to-do people, having only 20 to 30 head of cattle, would often have three or four visitors, some of whom lingered waiting for the evening meal.

Because of numerous guests, in the second half of winter a lot of people of average income would run out of food, which put them in dire straits. Therefore, hosts who did not welcome a concourse of unasked guests were rather common. These dissenters were called greedy, inhospitable people. They would cook their supper late at night, after all intruders had left.

On an occasion, a well-off host could be paid a visit by a rich toyon holding an important public office, together with his relations and friends. The hosts would make a feast in his honor: cattle were butchered; the guests were offered wine, kumis and some more exquisite dishes.

In fact, this treatment was a kind of a mandatory supply of provisions to an important person and his suite, a true survival of times past. The following day, the guests could take away some of the meat of the cattle butchered for them. The day before the guests left, the hosts would give them, apart from the compulsory provisions, other valuable things such as butter, silver decorations, coins, furs, and the toyon himself would often get a horse.

The more well-off and hospitable Yakuts, whose cordiality had no bounds, would have visitors continuously, in summer and in winter, and it sometimes ruined the hosts completely. These people were referred to as the people ruined, “eaten” by gusts.

Lunch “under the shirt”

If a guest was going to stay the night, his bed was carried into the yurt by the hosts or their servants, and made soft for him. The horse was given good hay. If the traveler was an honorable guest who had made a long journey, he could enjoy warm hospitality for several days. If a friend passed by without making a call, the Yakuts were offended and interpreted this as enmity.

More or les honorable guests and good friends were received very warmly and treated with best dishes. People belonging to the poor class were given second-rate meals. If there were many guests, the dishes offered were in line with the public and financial status of each guest.

The poor would willingly share their meals with guests and invite them to have potluck with them.

At small feasts and during occasions with many guests present, the cooked and not too hot meat was put on the table, where it was cut by the people who were skilled in it. The host or the person closest to him would stand nearby, stick pieces of meat with a knife like with a fork and distribute them among the guests, choosing the best and fattest bits for honorable persons. In exactly the same way other dishes were distributed: cooked insides, horse’s lard, frozen hayah (“white Yakut butter”). A similar way of distributing food was characteristic of ancient Mongols.

At large feasts the pieces of meat cut in advance were put into wooden bowls – kytyh – or birch bark buckets and carried to the sitting guests. Also, the guests were offered chorons filled with kumis and diluted butter.

At dinner or breakfast honorable guests were given large slabs of meat, each weighing 4 to 6 kilograms. The guest could take away the part of the piece he did not manage to eat and have it on the way back or give it to the members of his family on return. The meat would be wrapped in dry green hay and put in a leather bag. If the guest did not take the remnant of the meal, this would mean that he was not satisfied with the host and, moreover, that he turned down the generally accepted custom.

If the guest was a woman paying a visit to her relations or good friends, she would take the greater part of the lunch specially made for her (frequently, two big pieces of meat) home where her husband, children, and other adult members of the family were looking forward to her return. Those present at weddings, funerals and other occasions suggesting generous treatment behaved similarly. In the ancient times, a twin custom was practiced by Mongols.

Do not eat up happiness

Food occupies a highly important place in Yakut beliefs, mainly in what concerns sacrifice offerings and “negative” taboo magic. According to Yakuts’ beliefs, food (similarly to any other object) has a soul of its own, which is its quintessence, or vital principle, concluded in a material body. In part, it is this belief that underlies the theory of food sacrificing. For example, they used to put dishes with various meals and drinks in front of a god’s image; the offerings were later given to old people, who had to do with food without “soul.”

It was considered that if the “soul” evaporated from the food, it was a sign that a well-to-do family would grow poor and some of its members would die; in parallel to this, food would lose its taste. And then, no matter how hard the hosts tried to treat and feed their guests, the latter would never feel full. Sometimes at large feasts organized by cattle breeders, regular people would drink vast quantities of butter. This proved that the butter no longer had the soul quintessence or food properties. Basing on this view on food quality, the old people mentally predicted the degree of the hosts’ future material well-being and happiness.

For the Yakut cattle raisers, food, especially dairy products, were associated with richness and abundance in everything. If merry-makers drank and ate all the dishes offered to them without leaving anything behind, the hosts were considered to lose through it their material wealth and happiness. Partially underlying this idea is the principle of homeopathic magic: the like comes from the like. From these considerations, those who were present on the feast tended not to drink up and eat up all the dishes as this was seen not just as bad manners but also as a taboo, it was prohibited. It was so not because those were food remnants but because this could do harm to the hospitable hosts and their kin. Therefore, the old men used to say: “You must not drink the people’s wealth and abundance down to the ground because this is no good, and you yourself will not avoid punishment by gods.”

It was not allowed to pour milk food down on the earth as this would anger the gods who patronized horses and cattle and result in a loss of cattle, especially the youngsters. This is why wealthy cattle raisers would pour excessive dairy products of their household down into the nearest lake.

A spirit must be fed

In the epoch of developed animism, sacrificing to the good and evil spirits imagined as anthropomorphic creatures was nothing but treatment with different dishes and drinks. Sacrifice offering through fire was the main form of feeding gods and spirits, whose ceremonial worshipping during festivities and burial rituals was accompanied by mass meetings and feasts at which the meat of sometimes a large number of animals was eaten and partially burnt.

Gifts to gods-creators and patrons, and in general to the spirits of the Upper World were primarily dairy products, as well as meat and living cattle, mostly horses. The evil spirits of the Lower World were offered a bloody sacrifice: raw meat, clots of fresh blood, blood-producing organs, and blood vessels.

The food that served as sacrifice had to be untouched: gods or spirits were to taste it first. An illustrative example is the ban to drink the kumis prepared in early summer before it has been offered to gods. Drinking the first kumis before the ritual sacrifice even by the hosts themselves was considered to offend the gods, who took it as a sign of disrespect.

According to the traditional beliefs, successful husbandry, good crops of herbs and fruits, and people’s well-being depend on the disposition and good will of patron gods. During travel and at home, not to mention solemn occasions, Yakuts would always treat their gods before having a meal. A piece of meat was cut off the fattest part and put on burning coals. Fat from the soup would be sprinkled over the fire.

As for the sacrificial offering made by the Yakuts with the help of fire, Billings and other travelers who visited Yakutia in the 18th century wrote that “they not only bring the first spoonful of their food to the fire but give it the remnants of their everyday meals as they do not wash their clay dishes with water but clean it with the help of fire.”

The most widely spread food ban was the taboo based on the principle of contagious magic – transmission of negative properties from an object when it is contacted. For instance, in order to avoid in the future different diseases and ailments, not only children but young people as well were prohibited to eat certain organs and parts of the birds’ and animals’ bodies. Yakuts believed that some of them could be suffering from a sickness or ailment, and if people happened to eat the meat from the part of the body affected by a disease, they would catch it. This is why children were not allowed to eat blood vessels and bone marrow of the animals’ upper and lower jaws as some of them could have suffered from teeth or jaws illnesses.

Some taboos sprang from the homeopathic magic law mentioned before – the principle of similarity and imitation of negative properties. For this reason, girls and young women were prohibited to eat certain species of fish, birds, and animals so that in the future they did not give birth to babies who would possess the ugly or bad properties typical of these living creatures.

Also, there were taboos connected with the cult of patron gods and bans on the names of some food product. The things prohibited to the children and young people were allowed for old men including beggars and “bad” people who were not expected to live long anyway. However, even the old men would not have some organs considered inedible: glands, genitals, eye-balls, spinal cord, and neck sinews.

Look out! A taboo

All food-related Yakut taboos can be divided in four groups: I – taboos for the females; II – taboos for pregnant women; III – taboos for children; IV – taboos for everyone.

For instance, women were prohibited to eat divers, grebes, and seagulls (lest their future baby be born with a speech pathology or splay feet), lake lawyer or bear meat (a bear was considered to be a woman in the ancient times).

Pregnant women were forbidden to eat sinews (to avoid cramps at childbirth), meat of the animals killed for funeral feasts (otherwise the baby could sleep in the mother’s womb for three years instead to being born or remain numb or stutter for the rest of his/her life), the head and insides of waterfowl shot from a gun (otherwise the future hunter will have no luck), and so on.

Children and young people were not allowed to eat fried foods made from the lower part of hind legs: it was believed that because of this sores on feet and hands would not heal. And the taboo on the upper part of hind legs was attributed to the belief that the children may grow up lascivious.

SOME RITUALS OF SACRIFICING FOOD STUFFS, CONNECTED WITH THE CULT OF GODS AND SPIRITS

On the day a rich fiancée came to her husband’s home, the morning before the wedding feast, they used to install on a table opposite the fire-place a cooked horse’s head with blood sausages put on it. As the prayers were recited, kumis and butter was poured onto the fire or fat bits of meat were put on coals with a spoon, in three places. The cooked blood sausage made from horse’s meat served not only as sacrifice to the spirit-fire master but also as a treatment of honorable guests, which undoubtedly had a symbolic meaning. The heads (skulls) of pet old horses were hung up in a tree, after meat and fat has been scraped off them.There was a custom to put butter and a cattle heart cooked in one piece next to the newly-weds’ bedstead on the wedding night; the young couple was to eat it at night or in the morning; this was supposed to excite mutual affection and love of the young couple and was a kind of a magic act.

When rich people were buried, a lot of cattle were killed on their graves. Some of the meat was given to everybody present, and the rest went to the funeral feast organized by the dead person’s relatives. When the animal was butchered, they did not use to break its bones but cut it at joints. By legend, there were sometimes up to 70 head of horses and cattle killed. Together with the dead body, they would descend cooked meat and melted butter into the grave pit, and put a leather jack filled with kumis into the monument erected on the grave. These were the dead man’s provisions as he moved to the world of the dead.

When a magic act was performed with a view to summoning a petty evil spirit, so that it would be lured and caught, rank butter would be put on hot coals scattered on cracked pottery chips. The deceived spirit would greedily throw itself on the smoke and smell of the burning butter. At this moment, the shaman would go at it, catch it, and send back to the underworld.

The same act was performed when somebody wished to do away with his personal enemy. In this case, they would make a small fire, put next to it an effigy of a person made out of rotten wood, put rank butter on the coals, and continuously repeat magic words. Then they would strike a sudden blow with a weapon on the effigy. People believed that their enemy was to die shortly because of a disease developed in the organ struck in his wooden twin

Children in general had to obey a great many food taboos: For instance, they were forbidden to eat the base and tip of the tongue (so that not to be intemperate in speech or cantankerous); brain; the base of the tail (otherwise a young man who has become a son-in-law or a fiancée, being in a strange land, could involuntary make an indecent noise and find himself in an awkward situation); spleen; muscles of the inner and outer part of the shins and thighs, as well as muscles going along the back from waist down to the bottom (lest in the future they suffer from the cramps of these muscles), and so on.

Eggs were a taboo too – it was believed that children might become reticent or voiceless, or remain numb for good or stutterers at best.

Numerous taboos for adults included eating the meat of predatory birds: kites, hawks, eagles, owls, etc., as well as of herons, ravens, crows, cuckoos and others, as these birds are associated with the world of evil spirits and were, in part, totems. Neither was it allowed eating a bit of food that fell to the ground in the morning – it was considered that otherwise one could fall ill as this bit collected all the impure and bad things and so had to go to the fire.

The latter taboo was universal; it concerned everybody without any exception. Besides, it was forbidden to eat with the left hand, which equated with drinking one’s own blood. It was also prohibited to talk loudly and make noise over the newly prepared but not yet ready kumis leaven – this was considered to prevent the kumis from fermenting and bring about the “leaven’s death.”

Apart from this, there were hunting taboos on the names of products. These were attributed to anthropomorphism, which is enduing human properties to wild animals and the resulting necessity to conceal from them hunter’s intentions. Before going hunting to the taiga, a hunter would call food stuffs differently from his everyday life (for example, butter was referred to as “the fragrant”, meat as “the red”, and lard as “the spicy.”

Taboos on the names of certain edible wild-growing herbs have the roots similar to the taboos on the names of ancestors and profoundly respected persons. So that a plant was not offended when its real name was called, other names reflecting some of its qualities were given at the time when it was collected. Rush flower, for example, was referred to as “lake food” and fireweed as “grass of a burnt forest.”

Milk libations

Among the most important taboos was the prohibition to pour dairy products onto the ground as this, on the one hand, could cause the anger of patron gods and, on the other hand, bring about the loss of byia, happiness connected with abundance in dairy products, by homeopathic magic law.

From the ancient times, Yakuts had a custom prohibiting everybody including householders from drinking new kumis before the festivities of ysyah, or kulun kymyga, were held, which incorporated a libation ceremony to honor the patron spirits of cattle and animals.

The folk view was that kumis and butter was gods’ favorite beverage. During feasts it was a treatment for gods of the Upper and Middle Worlds – patrons of people and domestic animals, as well as for the Upper World’s celestials, who could send to people various diseases.

For the ceremony, kumis was poured into richly ornamented chorons, with tufts of white hair from the horse’s mane tied to the vessel legs. After reciting a prayer for granting people happiness, cattle, and children, innocent young men and girls would pour, three times and from three chorons, kumis and butter into the fire.

Besides, the white shaman, the good spirits’ favorite, or a person replacing him would sprinkle kumis, out of a special spoon, onto the horse consecrated to the Upper World spirits and onto the ground covered with green grass, which was a sacrifice to the female spirit of the vast world, the goddess of fertility.

Everybody gathered for the feast were offered big chorons filled with kumis. According to the established practice, the chorons were held in the hands and not drunk from until the ceremony of making libations to patron gods was completed.

In the Vilui regions, immediately after the ceremony was observed, chorons with kumis from which the libations were made were passed over to the housekeepers, who drank up the kumis together with their children. Underlying this ritual was the idea that the drinking by strangers of the kumis which had been gods’ beverage amounted to the housekeepers’ loss of their happiness and wealth.

The editors thank I. E. Vasiliev, research worker of the Barashin Museum of the Yakut History of Science with the Institute of Humanitarian Studies and Problems of Northern Minorities SB RAS (Yakutsk), for the photos