Mongolia: "… A Call from Afar Awakes My Soul"

“ ‘The soul of a nomad can hear a call from afar…’ A settled life for a traveler is like a cage for a bird… the mysterious voice from afar wakes up my soul and, again, calls it back… How many times did I feel genuine happiness facing the wild, grandiose nature; how many times ascended the extreme absolute and relative heights; how many times imbibed the beauty of magnificent ridges… Ever since ancient times the solemn grandeur of nature has commanded the attention of man…”

With this poetic declaration P.K. Kozlov—one of the greatest explorers of Central Asia—begins his book Mongolia and Amdo and the Dead City of Khara-Khoto. You cannot but agree with him, especially if a fair portion of your life is spent in expeditions. No matter what you do, before each trip you feel excitement, particularly intense if you are going to travel to the places little known to you.

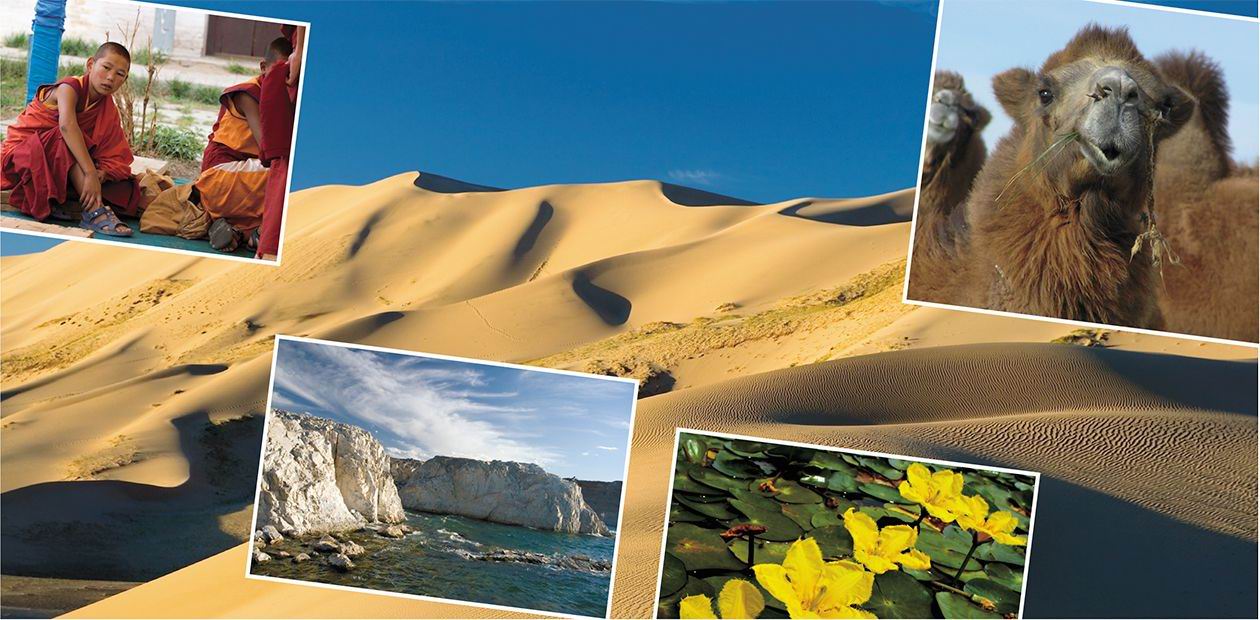

This is the way it was with us: setting off on our first trip to Mongolia, we could hardly imagine what a remarkable country it was. It goes without saying that we had a picture drawn in our mind based on literary sources and stories told by eyewitnesses, but it turned out to be a very rough reflection of the reality.

We have used very little academic data in this article. Instead, we are quoting some outstanding travelers who visited Mongolia in different periods. Their notes can continue to serve as a splendid guide for those whose soul is awaked by “a call from afar…”

“A Mongol… is true a nomad”

If you open up any geographical reference book, you will be surprised to discover that, apart from Mongols (mostly Khalkha-Mongols), this country is inhabited with many other peoples. These are Kazakhs (residing predominantly in the western aimaks), Bayids, Dorbets, Buryats, Zakhchins, Oolets, Torguuds, Tuvins, Khotons, Chinese, Russians and so on, though all of them taken together make up less than 10 % of the national population.

When you see the unsophisticated life Mongols lead, these eternal herds, and the harmonious blend of the people and the environment, it springs to mind that, in fact, so little has changed since the times of Chinggis Khan (except cities). Satellite dishes and solar batteries made in China do not disrupt this harmony but add a certain degree of piquancy to the picture.

A Mongol and his horse never part. We witnessed this more than once, and could not help admiring the dexterity and supernatural bond of man and animal. When some boys made up their mind to help a member of our expedition to catch dragon-flies in the bottom land of the Kobdo (Khovd) river, they quickly learnt how to use butterfly-nets and galloped daringly about the bushes, whooping every time they caught an insect. None of them left his horse—they were moving among the rocks like centaurs.

“A Mongol is a rider par excellence; also, he has sharp eyes, is used to the saddle and weather adversities, in a word, he is a true nomad… He breaks the monotony of his journey with prayers, songs, tobacco and tea… He prays at mountain passes, sings in the valleys, smokes and rests with a cup of tea in any yurt along his way…” (Kozlov, 1974).

These days, obviously, Mongols do not pray that often and yet stop at each pass where there is an obo and leave something there. If they have a chance, they will mark this event with a cup of strong drink. To make the road less dull, they will sing a song. As a rule, they have clear voices and sing beautifully and with pleasure.

Mongols move a lot and cover long distances. All their things they carry with them, mostly in the USSR-made cars—UAZs and ZILs. Although you can still see people moving like their grandfathers used to do, that is, using camels or yaks.

In the old days, Mongolia had 700 monasteries; now, there are much fewer of them. The monastery of Erdene-Dzu is one of the most ancient in Mongolia. It is considered to have been built at the place of Mongolia’s 13th century formidable capital—the city of Kharakhorum founded by Chinggis Khan in 1220. In 1586 Khalkhi Abtai-Khan ordered to build a Buddhist monastery opposite the former site of the city. As Mongolia’s first monastery was being erected, a lot of construction materials were taken from Kharakhorum ruins“A traveler, writes G. N. Potanin, is amazed at these wandering monasteries and altars with their numerous pantheons, roaming libraries, portable felted temples a few sazhens (a sazhen is 2.134 meters) high, literacy schools fit in nomads’ tents, wandering medical men, and moving infirmaries at mineral waters—all these things that one does not associate with the nomadic way of living; in terms of literacy prevalence, Mongols are undoubtedly the only nomadic people in the world” (Potanin, 1881).

“They carry their homes along everywhere they go”

Even though the total national population is not large (less than 3 million), you can see yurts and plenty of herds of various domestic ungulates in every valley. In all probability, this was the sight Marco Polo saw during his famous journey. “Their homes are made of wood and covered with ropes, round in shape; and they carry them along everywhere they go; these homes are easy to carry, they are tightly tied up with twigs…” (Polo, 1999).

The Mongols are very hospitable, and if you happen to be near them, you will certainly be invited to the yurt and offered a treatment. In contrast to other nomads, Mongols, despite a large number of cattle, prefer dairy food.

Obo (ovoo in Mongolian) is an ancient sacred place inhabited by the host spirits of the locality where they should be worshipped. Obos are constructed in sacred places where spirits have manifested themselves or where they act. As years go by, an obo grows in size because of the sacrifice stones brought here during annual rituals or left by travelers. Obos often spring up at mountain passes, where there are caravan paths; at the tops of worshipped mountains; in sacred places; and near Buddhist temples“They drink cows’ milk; and do it as though it were white wine, it tastes delicious and is called shemius.” (Polo, 1999).

“They make sour milk, kumis, and various cheeses… butter and tosu. Tea is had with very tasty urium, which is a thick plate of very dense cream skimmed from cooked milk, and tosu, a lumpy cheese mass that is a mixture of lard, millet, milk, and barley flour.” (Potanin, 1881).

Mongols, as a rule, are not importunate; if they pass by your camp, they will surely say hello and sometimes come closer to have a better look at the uninvited guests, but more often will just ride on. Mongolian children are overwhelmed with curiosity typical of all the children. They feel very much at ease and at the same time carry themselves with dignity.

Mongols love their children dearly, and yet inure them very early to the hard realities of life. Mongolian girls wear braids and smart, though sometimes not neat, tops. Relations between brothers and sisters, to say nothing of parents and children, are very moving.

The Gobi has a harsh climate. For a greater part of the year it is very cold here. Winter begins in mid-October and lasts almost till April. In May and at the end of summer, winds and sand storms rage, though they can also occur in mid-summer. The winds, these so-called sculptors of the desert relief, form rocks of weird shapes and grandiose masses of sand-hills.In comparison with Central Asia, the Gobi features a shifted rhythm of precipitation. If in Central Asia maximum precipitation falls in winter and spring, in the Gobi desert if occurs in summer, as a result of which the plants omit summer vegetation and wake up to life later.

As a rule, precipitation on the Gobi plains does not exceed 100—200 millimeters a year; in the central parts of large hollows, where summer heat feels stronger, raindrops may evaporate even before they reach the earth surface.

“... the face of Mongolian nature changes sharply”

We mostly explored the western part of Mongolia, though during our last trip in 2007 we crossed the border in the north and went across the country to Gurvantes, and then went to Khermen Tsav. The northern part of the country looks very different from the central and, especially, from the southern part.

Relief changes after Ulan-Bator (Urga). This is how P. K. Kozlov described this part of the country:

“And there goes Urga—the spiritual and administrative center — after which the face of Mongolian nature changes sharply, the mountainous relief smoothes down, the plant cover becomes poorer, and the population grows scarce, particularly to the south of the mountains that are an eastward continuation of the Mongolian, or Gobi Altai. Here lies the true Gobi desert that sometimes looks like a sandy and stony tablecloth and sometimes gently folds into rocky hills picturesquely lit with sunset in the evening hours… And, finally, southern Mongolia, almost all of which is a sea of quicksand, mostly ridges of meridian sand-hills often hundreds of feet high.”

Especially impressive is the quicksand of Khongorin Els, which is an extensive row of sand-hills whose height reaches 200 meters. On our return trip from Khongorin Els, we gave a lift to a Mongol who had on him a primitive metal detector. He was one of the so-called treasure trove seekers, who have recently became abundant in Mongolia thanks to the numerous “cultural miracles” found here. As tourism is developing, the demand for ancient artifacts is huge. In fact, ruins of ancient towns have always aroused interest, which was noted by P. K. Kozlov almost a hundred years ago as he was setting off to the ruins of the town of Khara-Khoto. “They told me that Torguuds come to the ruins and dig up looking for hidden riches…” (Kozlov, 1947).

It is not easy to describe your emotions when you see the Khermen Tsav canyans: all your feelings grow sharper when you realize that this place abounds in the remains of dinosaurs. As somebody aptly remarked, this is a kind of a communal grave of the Jurassic period.

Here, everything changes during the day. In the morning the landscape looks Martian: long shadows, red upright walls, and scarce plants found occasionally in dry river beds do not hinder the impression that you are on the “Red Planet”. As the day proceeds, the temperature goes up and by noon the heat becomes scorching. It is + 45—48° C in the shade, which makes being in the open quite difficult.

Dry ground and practically utter absence of vegetation encourage active windborne accumulation—generation of sand-hills from particles carried along by the wind. The greatest part of Mongolia’s sands is concentrated around lakes and along large dry river beds.In the hollow between the Sevrey and Gurvan-Saikhan ranges lie the sands of Khongorin Els. This unique sand tract displays a wide variety of eolic shapes. It is here that you can find Mongolia’s highest pyramid sand-hills (up to 200 meters), chains of sand-hills, cumulus and hummocky sands

In the afternoon, as the shadows stretch, you start seeing life everywhere: jerboas are fidgeting around, lizards are busying themselves in the bushes, and various beetles (darkling beetles mostly) are hurrying on. Later in the day, when the sun looms over the horizon, sinister shadows cover the quaint remains and clefts; a breeze comes up, giving rise to peculiar sounds in the narrow crevices— could these be ancient animals waking up?

“The Sea of Khiargass”

We devoted most of our time to the western part of Mongolia, namely, the Big Lakes basin. The basin is predominantly composed of slanting lowlands dotted with uplands and wavy areas. Also, you can spot stand-alone rocks or groups of rocks, hills, and sometimes even highlands made of sand and granite. In some places the basin is crossed by the ranges of mountains, branches of the Khangai or Altai.

A unique feature of the basin is that it is home to a few natural zones; to begin with, there are sand deserts, clayey deserts, and dry steppes. Along the mountain sides you can see high-grass steppes that often turn into forest-steppes.

Geese, ducks, sandpipers, cormorants, various kinds of herons, and other birds feel at ease on the numerous lakes of Mongolia. The seagulls (silver gulls, black-headed gulls and great black-headed gulls) and several species of terns form huge coloniesUp in the mountains there are mixed broadleaf and cedar forests; and as you go higher, these give way to tundra, alpine meadows, bald peaks, and permanent snows. The lowest parts of the basin have lakes and salt marshes. The largest and deepest of them is Lake Khiargass.

The lake located at the foot of the Khan-Khukhiy range stuns by its size and unique harsh beauty. The impressions of our first visit have remained vivid. Mongols call it Khiargass-Nur while we respectfully refer to it as the Sea of Khiargass. “Khiargass” is the Mongolian for “Kyrgyz”. As Mongolian legends would have it, at the time of the Great Migration from the Minusinsk steppes to the Tin Shan Mountains, tribes of Kyrgyz nomads would stop here.

The main water arteries of Western Mongolia are the rivers Tes and Khunguy springing from the Khangai Mountains and the full-flowing Kobdo running from the west. Virtually all the other quite numerous rivers come to a stop as they leave the mountains, resulting in alluviums and gigantic debris conesThe legends do not lie: in the vicinity of the lake you can find a great many burial-mounds and statues that belonged to the ancient Turks. The Dzabkhan River carrying its waters down from the Khangai range flows into the lake. At the river mouth, the freshwater lake of Airag is formed, which is separated from the salty Khiargass by a narrow isthmus.

The result of the three expeditions we made to Mongolia was that we were enchanted by this harsh yet wonderful Eden. And time has not healed this affection: we are still attracted to its expanses, its gorgeous and various landscapes, its animals and plants… Also we have preserved the memory of the amazing buoyancy, kindheartedness and hospitality of the people who inhabit this land—people over whose souls and way of life the time has turned out to have no authority.

“What is conspicuous at the very first meeting with these people is their level of culture that makes us acknowledge that the Mongols have not lived fruitlessly; what we see there proves that even in such a lonely and poor country as Mongolia people can lead a peaceful and cultural life” (Potanin, 1881).

References

Mongolia and Amdo and the Dead Ciry of Khara-Khoto by P. K. Kozlov. Moscow, 1947. 328 p.

A Book about the Diversity of the World by M. Polo. St. Petersburg, 1999. 381 p.

Essays of North-Western Mongolia by G. N. Potanin. St. Petersburg, 1881. Volume 1 (425 pages) and Volume 2 (268 p.).