Nomads' Gold. On the "Siberian Collection" of Peter I

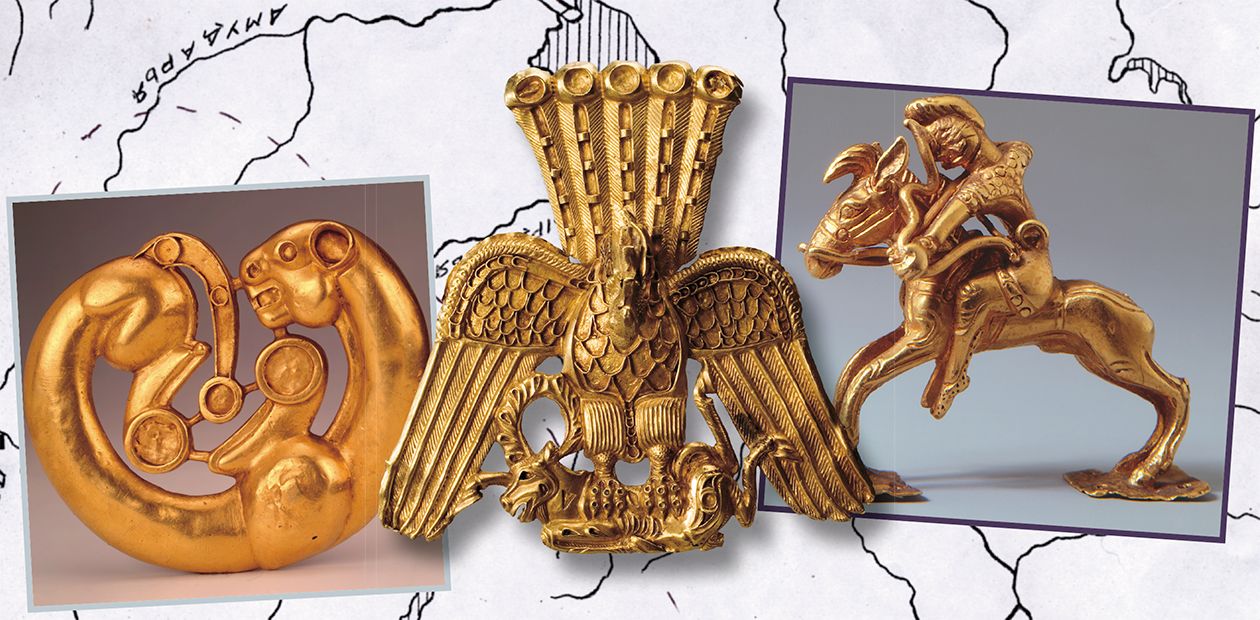

Russia’s earliest archaeological collection is actually the so-called Siberian collection of Peter I – about 240 unique gold artefacts related to the ancient nomads of Eurasia and kept in the Hermitage

The outstanding story of this famous archaeological collection reflects the spirit of Peter’s epoch, the time of radical transformations occurring in all spheres of public and private life. Apart from the economy, drastic changes took place in people’s minds, stirring up their investigative abilities and arousing their interest in the outside world. The Russia of Peter I, impetuously turning into an empire, encouraged research into the history and geography of the peoples inhabiting it. Crucial to the spirit of the time was the remarkable personality of the Tsar with his keen and tireless mind and unbounded scope of interests. The great statesman and reformer was more than a curious collector of antiquities — his collections covering various branches of knowledge formed the basis of the Kunstkamera, the first Russian museum established on Peter’s initiative in 1714...

It was Peter I who created the first collection of archaeological antiquities, which has been known since the 19th century as the “Siberian collection of Peter I.” To the end of his days, the Siberian collection remained in Peter’s palace — testimony to his special attitude towards it. After the death of Peter I and his wife Ekaterina I, the Supreme Secret Council was apprehensive that the ancient gold might be divided among the heirs. To prevent this, the curator of the collection, court quartermaster P. I. Moshkov made a list of the artefacts, in accordance with which the collection was taken to its new home, the Kunstkamera, on December 22, 1727. For a long time, this handwritten list was the only document shedding faint light on the origin of the objects from the collection since accompanying letters and registers got lost among other papers of Peter’s epoch.

In 1859, during the reign of Alexander II, the collection was transported to the Winter Palace and handed over to the Hermitage. In late 19th century the archaeologist A. A. Spitsin discovered, in the archives of Peter I, a few interesting papers related to the collection brought from the Kunstkamera. Later, a high number of scholars of this country studied the collection and its history: V. V. Radlov, I. I. Tolstoy, N. S. Kondakova, S. I. Rudenko, and many others.

Hunters for the treasures of “Tatar graves”

The ancient gold kept in the Kunstkamera and then in the Hermitage became an enigma as early as in the 18th century. The objects making part of this collection not only originated from separate archaeological sources but had been created in different periods, from 7th century B.C. to 2nd century B.C. Back in those times, Siberia was inhabited by nomads, who buried their dead at tribal cemeteries. Gold artefacts occasionally found at ancient graves in the 17th—18th centuries — the period of Russians settling down in Siberia — spread a lot of rumors about countless treasures.

The possibility of getting easy money attracted treasure seekers: burial grounds of tribes’ chiefs with expensive golden objects became the source of a profitable business. Tomsk and Krasnoyarsk voevodas (commanders) fitted out detachments of the so-called bugrovshchiki (“hillockers,” or mound-diggers), whose loot was at times very rich (burial-mounds of ancient nomads used to be called “hillocks,” or “Tatar graves”). These expeditions were of an ambiguous nature: on the one hand, their participants were entrusted with the national goal of developing Siberia, as they made maps and searched for gold deposits (ancient burial-mounds were at the time considered as such!); on the other hand, members of these raids could make their fortune through barbarous excavations of ancient graves.

Detachments of “hillockers” counting 200—300 people had a real seasonal business, digging graves from spring through fall. The objects found were sold at the markets of big Siberian towns. Siberian mounds were robbed to such an extent that in the 17th century rumors about burial artefacts reached Moscow.

One of the earliest documents on Siberian “grave” gold was discovered in the Chancellery of the Siberian Province in 1708. It was a copy of the dispatch dated by the year 1670 to the Tsar Alexey Mikhailovich to the effect that in the Tobolsk uyezd (region of a province), “Russian people dig out gold and silver things, and dishes in Tatar graves.” This information made the government bodies interested in the source of “grave gold.” From the early documents making reference to the precious finds, it became clear that the area in question encompassed Siberia, the Urals and part of Central Asia.

Witsen’s collection

One of the first people to value highly the collection of Siberian antiquities, both from the artistic and from the historical point of view, was the Dutch scholar Nikolaas Witsen. Having arrived in Russia in 1664 as a member of the Dutch embassy, he stayed for a year, collecting geographic, linguistic and ethnographic data. After leaving Russia, Witsen continued to communicate with his Russians correspondents — he spent 28 years to collect materials for his fundamental work, the book about Russia North and East Tartary.

Through his Russian agents, Witsen purchased valuable artefacts from the ancient burials, as well as bronze and iron objects usually thrown away by the bugrovshchiki. The scholar was amazed by the contrast between the shabby life of indigenous population and the prevalence of precious art objects in the old days: “How civilized must have been the people who buried these rarities! The gold objects are so artfully and sensibly ornamented that I don’t think European craftsmen could have managed better.”

In his book, the scholar mentions the silver cup given to him by the boyar F. A. Golovin. Golovin had taken possession of the cup when he was going through Siberia to China for negotiations. In the place where the Irtysh fell into the Ob, the eroded bank revealed an ancient burial with silver bracelets and a cup. This vessel was shown in a geographic table made by a Dutch draftsman on Witsen’s order with a view to depicting how the rarities he had collected looked.

The attempt of Peter I to acquire the collection after Witsen’s death failed — the objects were sold at an auction and their further destiny is unknown. In the 19th century, however, researchers noted a striking resemblance between the objects depicted in Witsen’s tables and some objects from the collection of Peter I handed over to the Hermitage. Though no exact counterparts were found, some objects like belt plaques or temple pendants must have formed pairs.

For example, the belt plaque from Witsen’s table depicting a wolf struggling with a snake pairs with the similar plaque from Peter’s collection: without doubt, they were found in the same mound. Judging by his letters, Witsen acquired this object in 1714. The twin plaque must have been handed to Peter I at about the same time. The Russian tsar was acquainted with Witsen, held him in respect and considered him a great authority.

It has been speculated that many objects from Peter’s collection were presented to Ekaterina I by the factory owner Demidov on the occasion of her son’s birth in 1715. This speculation is based on the following excerpt from the work by I. I. Golikov dedicated to Peter I: “During one of Demidov’s visits to St. Petersburg, the monarch’s son was born, Tsarevich Petr Petrovich. When the nobles congratulated the monarchess and, according to ancient tradition, presented her with generous gifts, Demidov gave Her Majesty expensive golden things from Siberian “hillocks” and a hundred thousand rubles, which was an extravagant amount for the time.” However, since the author makes no mention of Demidov’s initials, nor supplies a list of the objects presented, any identification is out of the question.

Gold for the sovereign’s treasury

The main sovereign’s supplier of golden artefacts became the Governor or Siberia, Prince Matvey Petrovich Gagarin, a rich grand and a noted character in the Tsar’s intimate circle. It was in Tobolsk, the then capital of Siberian province, that a great part of the objects from the Siberian collection was kept; in line with the Tsar’s instructions, they were subsequently transported to St. Petersburg, in small batches.

In the notes of Dalmtovsky Uspensky monastery there is evidence that as early as in 1712 the voevoda (commander) Prince Meshchersky sent people, on the order of Prince Gagarin, to search, with the help of poor peasants who had found shelter at the monastery, the interior of mounds for gold, silver, copper and other things for the sovereign’s treasury.

The Tsar’s decree dated February 13, 1718 instructed to collect everything that was “very old and extraordinary” and promised award for the old things found in the ground or in the water.

The Governor was charged with, among other things, gathering data on the possible sources of obtaining gold. Archival documents on the subject are scarce, because everything that concerned gold deposits and could give clues to finding this precious metal, including, probably, the co-ordinates of “hillock” excavations, was a closely guarded secret.

In 1721 Prince Gagarin, the sovereign’s deputy in Siberia, was hanged “for the abuse of authority and obstinate concealment of accomplices,” relying on the report made by the ober-fiskal (senior supervisor) Alexey Nesterov, head of the service set up on Peter’s order for conducting surveillance over all government officers. It was Nesterov’s duty “to survey everybody without their knowledge and find out about unjust affairs, including money raising,” which he performed so zealously that a high number of well-known statesmen, including senators, caught in accepting bribes or in treasury embezzling had to pay their lives for the abuse of power.

Investigation proved Prince Gagarin guilty of many other crimes. The full confession of guilt and late repentance did not help: the former Governor of Siberia was hanged in front of the building of the Ministry of Justice in the presence of the Tsar, dignitaries and unfortunate relations. A few days later, the executed was hanged for the second time and displayed to the public for edification. Bergholtz wrote in his diary that “for greater intimidation, the body of this Prince Gagarin will be hanged for a third time on the other side of the river and then sent to Siberia where it shall rot at the gallows.”

Fifteen pounds of rarities from “the land of ancient treasures”

The parcels sent by Prince Gagarin can be considered the earliest contribution to the Siberian collection. The first of these contained only 10 items, which were examined by the Tsar according to the list and handed over to Moshkov for keeping. The second parcel sent from Tobolsk had 122 items — in terms of its contents, nothing that had arrived from Siberia before or would be sent afterwards could be compared with it. As the parcel arrived when the Tsar was absent, the objects were received by P. I. Moshkov. Gagarin wrote in the accompanying letter: “Your Majesty has instructed me to search for the old objects buried in the land of ancient treasures. According to this instruction of Yours, I am sending You as many gold objects as it has been found. Descriptions of these objects and data on their number and weight are enclosed to this letter. Your Majesty’s humblest slave Matvey Gagarin. Tobolsk, year 1716, twelfth day in December.”

Enclosed to the letter was a list indicating the weight of the objects, which allowed their identification with the artefacts from the Hermitage collection. The last items on the list were “twenty small gold objects for Tsarevich Petr Petrovich found together with the objects described above.” These twenty objects intended for the young heir have yet not been identified in the present collection, though it must be them that gave foundation for the Demidov’s gift speculation.

Yet another document, dated October 1717, mentions sending a third parcel of Siberian artefacts including 60 gold and 2 silver objects. Their identification though is a problem because of the muddle in the archival papers. Of great interest is another document of the Tyumen voevoda’s (commander’s) chancellery kept in the State Archive of the Tyumen oblast (region) in Tobolsk, which gives evidence about the search conducted by Prince Gagarin on the Tsar’s order for the gold and silver “grave objects” found and sold by the “Tatars”. The paper indicates the weight of the objects sought — 15 pounds, which coincides with the weight of the artefacts contained in Gagarin’s third parcel, which means it might have held the “hillock” artefacts found.

“To punish grave diggers by death…”

The glitter of gold did not mislead Peter I about the highest artistic level and great scholarly value of Siberian artefacts. Owing to his good judgment, ancient gold was not melted in furnaces to turn into hard cash but has been preserved to this day as part of the unique collection. Peter the Great was interested in archaeological antiquities for yet another reason: the Tsar entertained the idea of compiling the complete annals of Russia and the peoples inhabiting it. Siberian gold, similarly to other “old things and coins of all rulers and tsars” could have “enriched ancient history.” This project was not put into effect because of the sovereign’s premature death.

Evidence of remarkable artefacts found in Siberia, which has reached the capital, and a few parcels sent by the Governor of Siberia made Peter turn his attention to the looting of archaeological valuables and issue a number of decrees — in fact, the first decrees designed to protect monuments to the past. Apart from the order to send all the artefacts to St. Petersburg and to hand them over to the treasury, the Tsar decreed that all the grave diggers “searching for gold stirrups and cups” be punished by death if caught. The far-seeing Tsar wished not only to keep the artefacts themselves but also to have reliable information about them, so he required that “all the objects found be drawn.”

The latter order must have proved impracticable, judging by the absence of archival data on the exact location and circumstances under which objects from the Siberian collection had been found. We cannot fail to mention though Peter’s attempt made in 1716, following his visit to Doctor Breyne’s natural history museum in Danzig, to organize research in Siberia. The Tsar asked the scholar to refer him to a colleague who could be charged with scientific work and information gathering for research in Russia. Breyne advised the Tsar to contact Doctor of Medicine Daniil Gotlib Messerschmitt, who had profound knowledge of history, geography, botany and other areas.

Messerschmitt was invited to St. Petersburg, where he signed the contract that obligated him to go to Siberia “to describe it physically” and “to search for various rarities.” In his report dated April 18, 1721 the scholar wrote: “By His Majesty’s order, in Siberian Province and in all the towns I shall look for herbs and flowers, roots, birds and so on…and also for ancient burial objects, copper and iron and cast shaitans (devils), portrayals of people and animals, Kalmyk mirrors; and I am ordered to announce in towns and uyezds (regions of a province) that everybody must bring me such herbs and roots and flowers and ancient burial things and all the other things indicated above; and if any of them are found worthy, the burial objects shall be paid for generously.”

On the whole, in seven years Messerschmitt’s expedition “did not procure any curiosities” — this may be attributable to the scholar’s excessive thrift: he bargained stubbornly with finders of “hillock” artefacts, evaluating them mostly based on the weight of metal, and not on their artistic quality. Having noted the scarcity of worthy objects, Messerschmitt came to the conclusion that by the time of his expedition all rich mounds with gold artefacts had been robbed.

In order to ascertain that it was true, Messerschmitt dug a few ancient burials in 1722. In the burial dug next to the Abakan ostrog (settlement) the travelers did not find anything of value, but Messerschmitt made a sketch of the burial. Actually, in Russia this was the first attempt to carry out archaeological excavations with scholarly purposes. Neither did excavations of other Siberian burial grounds produce the desirable result — there was no gold in the graves.

There is no doubt that after Gagarin had sent his parcels from Tobolsk, very few Siberian antiquities arrived in St. Petersburg, though it is evident that some objects became part of the Siberian collection after the death of Peter I. The “hillock” business lost its mass character, partly owing to the government’s bans: thus, in 1727, the Senate issued the decree prohibiting grave-digging under pain of severe punishment. Interestingly, this was done not to protect ancient monuments but to save the lives of mound robbers who were often killed by the local population.

Later additions

And yet — what do we know today about the places where the objects comprising Peter’s Siberian collection were found and the circumstances in which they were found? Most of them are likely to originate from the ancient monuments located in the steppes close to the Altai mountains, between River Ob and River Irtysh.

Tobolsk “hillockers” were searching for gold-bearing mounds along the rivers, including River Iset’ — moving upstream, they crossed the Urals. Thus, in 1718 the diggers handed in to the treasury small gold and silver objects discovered in the South Urals, close to Ufa, which later became part of the Siberian collection.

The collection contains a lot of objects richly ornamented with turquoise whose style resembles that of the artefacts originating from the Sarmatian monuments of the Lower Volga and Lower Don regions. This similarity may not be attributed entirely to the genetic kinship between the nomads of South Siberia and the Sarmatian tribes who settled west of the Volga at the beginning of our era. Objects from the Volga region could have become part of the collection without being documented properly. For example, Das Veranderte Russland by Weber (1721—1739) makes reference to some antiquities found in the epoch of Peter I between the Volga and the Urals and later sent to St. Petersburg.

The German scholar G. F. Muller is often considered “the father of Siberian history” because he has collected invaluable data on the history, ethnography and geography of Siberia. As a member of the Siberian expedition of 1733—1743 headed by V. Bering, Muller collected antiquities which were purchased in 1748 by the Academy of Sciences for the Kunstkamera and also became part of Peter the Great’s Siberian collection.

Among Muller’s outstanding acquisitions was the miniature figure of a galloping archer, cast from gold, which he had purchased at the Kolyvan-Voskresensky plant in 1734. In Muller’s time, ancient graves produced no more remarkable gold artefacts, therefore the travelers mostly purchased art objects made of bronze. In 1764 Muller wrote: “I saw a lot of people in Siberia who used to do this [grave-digging] for a living, but in my time nobody was doing it because all the graves that could have held treasures had already been dug.”

Despite the investigators’ attempts, the origin of many objects from Russia’s first archaeological collection — the Siberian collection of Peter I — is an unsolved mystery. This, however, does not diminish the huge scholarly value of this unique collection of masterpieces produced by the ancient nomads of Siberia and by their neighbors. Some objects, clearly originating from Iran, have close analogues among the artefacts of the famous Amu Daria treasure kept in the British Museum.

The Siberian collection comprises exceptional artefacts created during different periods in Siberia’s history and in different regions. The collection has become Russia’s unique cultural testament to the first quarter of the 18th century, and researchers continue to investigate the people and the periods in which these unique objects were created.