Messerschmitt's Archaeological Collection "Comes Back"

Following the order issued on November 15, 1718 by Peter I, Doctor Daniil Gotlib Messerschmitt was commissioned to go to Siberia “to find various rarities and pharmaceutical objects: herbs, flowers, roots, seeds and other medicinal components.” All scholars of the naissant Russian archaeology refer to his name because Messerschmitt was the first to do archaeological excavations in Siberia, in which he was driven neither by mercenary motives nor by curiosity but solely by investigational interests. The collection of Siberian antiquities he brought to St. Petersburg became the gem of the Kunstkamera and marked the beginning of academic research in archaeology

Having completed his studies at the Universities of Jena and Halle and having defended the thesis “On Reason as the Main Basis of Medical Science,” Doctor of Medicine D.G. Messerschmitt came back to his native town of Danzig to practice medicine. At the same time, he assisted Johann Philip Breyne in his investigations and helped him make collections for the Museum of Natural History Collections Breyne had founded. It was in this quality of a collector and investigator that Messerschmitt was recommended by Breyne to Peter I. The life-physician to the Russian Tsar R. Areskin, who also was the curator of the Peter’s Imperial Museum, or Kunstkamera, once dropped a hint to Messerschmitt that in the future he could become head of the Imperial Museum — a very enticing promise!

In 1718 Messerschmitt arrived in St. Petersburg, and in the following year he went to Siberia, as directed by Peter I. You will recall that back in 1719 Russia had no Academy of Sciences yet, and Messerschmitt was registered with the Chancellery of Medicine. This explains why his assignment was phrased so as to be appropriate to the tasks set for such an establishment: to collect everything related to medicine. When in Siberia, the scientist expanded his mission: he began collecting the materials that could “serve to enrich and adorn the Tsar’s library and museum.”

As for the latter task, he managed brilliantly, and the collection of Siberian antiquities he brought to St. Petersburg became the gem of the Kunstkamera and marked the beginning of academic research in archaeology.

Journey to Siberia

In the course of his Siberian expedition, Messerschmitt covered very long distances. On September 5, 1719 he left Moscow for Kolomna, then went down the Oka and Volga to Kazan, and then traveled by sledge to Tobolsk, where he stayed until March 1721. His further itinerary included Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk, the Sayan mountains, Mangazea, Irkutsk, the Nerchinsk factory, and Yeniseisk… Messerschmitt returned to Moscow on January 31, 1727. His expedition lasted the long and difficult seven years and deserves a separate investigation, the same as the personality of this extraordinary scholar of universal knowledge. We will only describe, in brief, the unpleasant position he found himself in.

His expedition completed, Messerschmitt came back to St. Petersburg. By that time, the new scientific center — Academy of Sciences and Arts — had been established. This was why Messerschmitt’s collections had to go to the Academy of Sciences or, to be more exact, to the Kunstkamera, which, by that time, had been ascribed to the Academy.

On Messerschmitt’s return, however, his collections were sealed on the order of President of the Chancellery of Medicine I. D. Blumentrost. The pretext was that Messerschmitt did not give all the objects he had brought from the expedition to the Chancellery of Medicine but kept them in his home. The scholar was instructed to transport all the collections, including his own, to the Academy of Sciences for investigation. A special commission was set up for this purpose. Messerschmitt was on it, and young G. F. Muller was appointed secretary.

The commission evaluated highly the collections and decreed to give them to the Academy of Sciences. As for Messerschmitt’s personal acquisitions, he received back only those that, in the commission’s opinion, the Academy did not need.

Life of the scholar and his collections

In 1728 Messerschmitt left Russia. The collections he took with him were drowned in a shipwreck. Having stayed in Danzig for two years, the scientist came back to St. Petersburg and lived in poverty, supported only by the charity of some people who treated him kindly, including the famous Pheophan Prokopovich.

How come Messerschmitt’s knowledge and experience were redundant at the time when the Academy of Sciences, represented by L. L. Blumentrost and J. D. Schumacher, was sending out invitations to scientists all over Europe to come to work to St. Petersburg? Could it be that the Blumentrost brothers, one of whom headed the Chancellery of Medicine and the other the Academy of Sciences, conspired against him? Or the young academic society of St. Petersburg did not want to have such a strong competitor in their studies of the unique Siberian collections he had brought? No documents have yet been found to answer these questions. Therefore, in order to restore historical justice and give due to this outstandingly hard-working enthusiast, Daniil Gotlib Messerschmitt, let us try “to reconstruct” the collections of antiquities he brought from Siberia.

Later, G. F. Muller wrote about the size and value of the collections brought by Messerschmitt that the Kunstkamera had been enriched beyond expectations. What are the sources that could help us restore the archaeological part of Messerschmitt’s collections and how reliable are they?

Let us bear in mind that, on the whole, the so-called arificialia, i. e. the objects created by man, were not studied as well as the naturalia, or the natural science collections. This is attributable, in the first place, to the situation with science and humanities in the 18th century: natural sciences were developed quite well whilst the humanities were at an early stage.

Another reason was that at the beginning of the 19th century the Kunstkamera building became too small for the constantly increasing number of museum objects, and, as a result, some objects were transferred to other museums. Some artefacts went to the newly established Asian Museum. A number of collections were, from time to time, taken to the Hermitage and returned back to the Kunstkamera. As a result of these moves, records of the origin of some objects were lost.

All these considerations refer in every respect to the early archaeological collections, including these of Messerschmitt. In order to establish the origin of specific artefacts from his collections, that is to attribute these objects, we must solve the minimum of three tasks.

First, to reconstruct, based on documents, the complete list of antiquities brought to the Kunstkamera; second, to attribute these objects and supply each of them with an up-to-date scientific description; and third, to search Russian museums for these objects.

Looking in the archives

To begin with, let us turn to the archives. Thanks to the fact that Messerschmitt scrupulously compiled catalogues of his collections, we have a most important source for reconstruction. Both the catalogues made for each parcel and the final catalogue should be taken into account.

As early as in 1720, Messerschmitt sent to St. Petersburg from Tobolsk several parcels. According to the lists enclosed to the parcels, these contained, among other things, drawings of various antiquities: coins, ornaments, statues, and pagan cult objects. It was about these first findings by Messerschmitt that Office Counsel of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences J. D. Schumacher reported to the Paris Academy of Sciences in 1721. The French newspaper Gazette de France wrote about “a high number of bronze statues found in the woods at Kalmyk burial grounds. Among those the Tsar ordered to put in his study were a Roman lamp in the shape of a Roman general on horseback with a laurel wreath on his head; two figures of people on horseback and in armor worn in the West in the 12th—13th centuries; and a lot of Indian idols, including the goddess used to be worshipped in China and in the Tibet.”

The final catalogue compiled by Messerschmitt and comprising 36 archaeological artefacts alone makes part of the third volume of his manuscript Sibiria perlustrata... (Description of Siberia, or the Picture of the Three Main Kingdoms of Nature). These descriptions, however, vary in format; most of them refer to a group of objects. For example, # 94 is “copper depictions of animals, some used for magic, others for unknown purposes.” Also, the number of objects falling under this description in unknown.

This is why another important source necessary for the reconstruction of the collection is drawings enclosed both to the separate reports and to the final report. In his Siberian journey, Messerschmitt was accompanied by Karl Shulman, a Swede, who made drawings of rock carvings and purchased “burial things,” as instructed by the scholar.

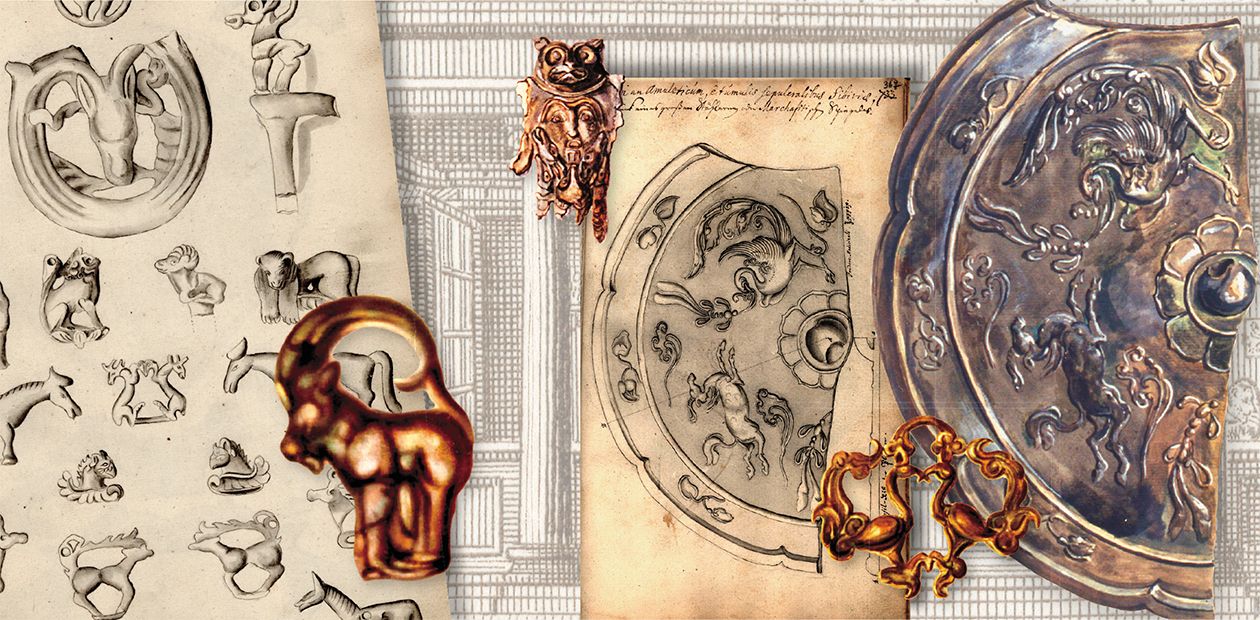

Some of the drawings were made by Messerschmitt. Each description should have had an accompanying tabula, a drawing depicting the object described. For unknown reasons, such a tabula did not come with each description. Therefore, watercolors of the so-called Paper Museum * turned out to be of great help for the reconstruction of the collection.

In the 1730s—1750s museum collections of the St. Petersburg Kunstkamera were drawn by academic draftsmen, mostly students of the Chambers of Drawing and of Engraving. This is also true of the antiquities collection brought by Messerschmitt and depicted on the drawings preserved. For example, in his final report Messerschmitt wrote about a bronze incense-burner in the shape of a four-legged animal, perforated from all sides. There was no drawing enclosed to the manuscript, but we have found this bronze incense-burner in the Paper Museum.

By comparing expedition drawings from Messerschmitt’s reports and watercolors produced in St. Petersburg we can find depictions of the same objects. The quality of the drawings produced in the field was, as a rule, not very high, whereas the Kunstkamera watercolors allow us to see the details indiscernible in the field drawings.

From travel notes

Regrettably, the catalogue of Kunstkamera’s collections Musei imperialis Petropolitani vol. 2 published in 1741 gives us no clues to Messerschmitt’s collection. If the first volume describing the naturalia contains some references to Messerschmitt, the second volume is silent on the origin of the objects making up the art collection.

It is our good luck that there is yet another source for reconstructing Messerschmitt’s antiquity collection — his travel notes. Even though our traveler did not put everything on paper, he sometimes described the objects acquired and how they were purchased or excavated.

Here are some of these notes:

April 4, 1721: “H. Doctor purchased a few small burial idols made of yellow and red copper for ¼ ruble. These include a cast camel and human figures…”

April 17, 1721: “Warrant officer Zeimern told us that lieutenant Grab, who had just returned from the town of Narym, saw, in the Governor’s house, a red shaitan (evil spirit) made of yellow copper, shaped as a semi-beast, semi-man, ¼ lokot’ (c. 10 cm) in size. He said that if we wrote major Borlyut about it, he’d get it for us.” Possibly, it is this red shaitan that made it to the St. Petersburg Museum as part of Messerschmitt’s collection and is depicted on a Kunstkamera drawing.

It is known that in Tobolsk Messerschmitt met captain Tabbert, a Swede taken prisoner during the war between Russia and Sweden. They made friends and followed part of Messerschmitt’s route together, doing joint investigations. The captive’s fate was luckier than that of the Russian officer: when Tabbert came back home, he started doing science and was awarded an aristocratic title — he became Baron Stralenberg. The book he published contained reference to the objects Messerschmitt had brought to St. Petersburg.

For example, here is a metal plaque depicted both in Messerschmitt’s manuscript and in Stralenberg’s book. Messerschmitt described it as an amulet, polished on the one side and beautifully carved on the other: in a garland of verdure, pairs of hounds attack a fox, a lion, a deer and a hare; also, there are letters along the plaque’s edge.

This is what Stralenberg wrote about the amulet: “The Tatars hang four such medals on their superiors — two on the shoulders, one on the chest and one on the back… The Russians took this medal, or plaque, from the Ostyaks near Samarov, who considered it as a rarity and worshipped it.” This was one of the objects described and depicted both by Messerschmitt and by Stralenberg. The latter often made note of materials the objects were made of and of their purpose.

Understandably, D. G. Messerschmitt failed to describe in detail all of his findings and acquisitions. Often, the travel notes only say that the doctor purchased some burial things, mostly made of red and yellow copper, or that Petr, Messerschmitt’s assistant, brought “some trinkets from the burial grounds.” However, if we compare a few sources and put them all together, we will obtain a most interesting picture of the objects Messerschmitt brought to St. Petersburg.

The reconstructed collection of archaeological antiquities brought and sent by the scholar to St. Petersburg has about 500 items! Even these few that can be shown within the limited space of this article stagger the imagination and make us admire not only the mastery of the artists who produced these objects but also the farsightedness and prevision of Daniil Gotlib Messerschmitt, a pioneer of the naissant branch of knowledge — archaeology.

The manuscript of D. G. Messerschmitt’s travel notes is kept at St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Published in: Messerschmidt D. G. Forschungsreise durch Sibirien, 1720—1727. Bd.1—4. Berlin, 1962—1968.

For the most complete biography of D. G. Messerschmitt in Russian see Daniil Gotlib Messer-schmitt by M. G. Novlianskaya. Leningrad, 1970, 184 pages.

*You can read about the Paper Museum in SCIENCE First Hand #3(9), 2006.