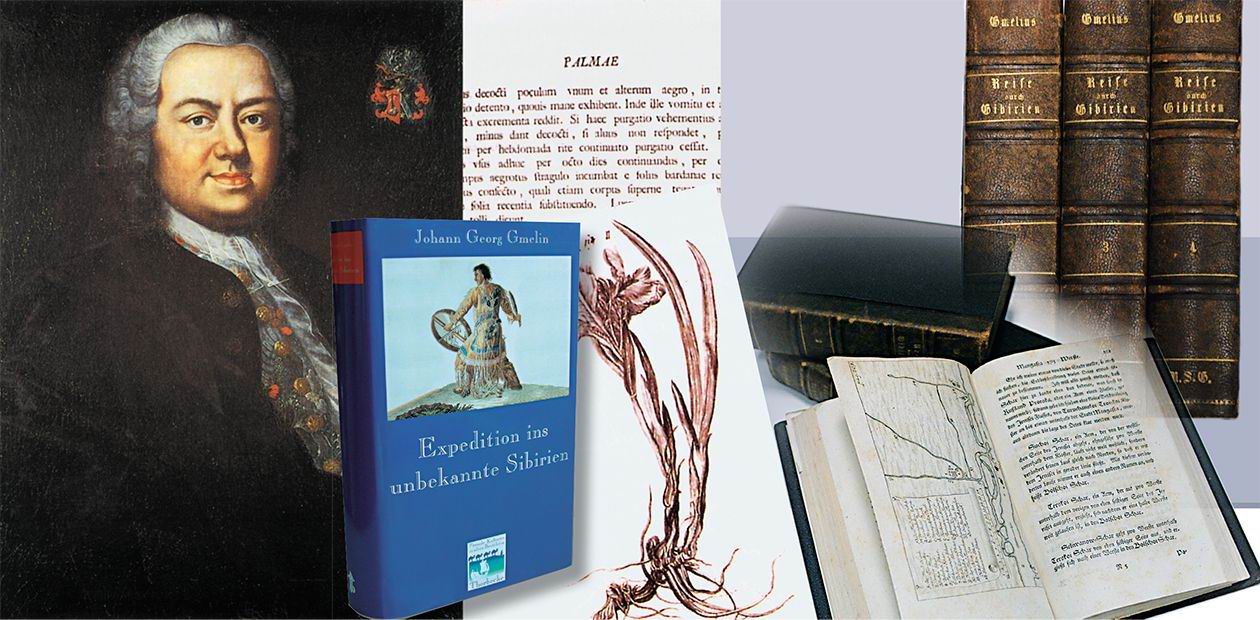

Non-Returnee. A Story of One Escape

Speaking about Gmelin, one cannot pass over in silence an amusing fact of his biography, namely his failure to return to Russia after vacation and disagreeable administrative hearing related to this event.

Yes, Gmelin was a ‘non-returnee’. This circumstance might explain the suspicious attitude of the St. Petersburg Academy to his Journey across Siberia and the Academy’s reluctance to translate the book into Russian. Actually the initial rejection of the monograph was to a certain extent of ideological character, then, as it usually happens, the negative attitude continued by inertia, as a result we still do not have a Russian version of this remarkable book. Well, this is only guesswork, which seems to be quite realistic. As an excuse to our compatriots, we should mention that the full text of the book is nonexistent in modern German either. In this regard, Gmelin and his Journey… had bad luck. We have no choice but to hope that this is not a final sentence and the story may have a happy end...

It is not a secret that throughout the 18th century the St. Petersburg Academy was staffed entirely with foreigners, mainly with Germans. There were no Russians among the first members of the Academy, the first Russians penetrated in the Academy in the middle of the 18th century, first these were isolated instances, then the process accelerated and intensified. It is clear that Russian academicians could not appear from nowhere in 1725. It is also clear that sooner or later, when their research was recognized by the European scientific community, many St. Petersburg academicians got discharged from office and came back to their homeland as honored heroes with honorary titles, dignities and merit pensions.

This was a legal and official way, but the case of Gmelin was completely different. Bluntly speaking he just escaped to Germany. He signed a new contract with the Academy, asked for a one-year vacation, took all materials collected in Siberia, which belonged to the Academy, and … did not return from the vacation. The point is that most probably he was sure that he was not going to come back already when he signed the new contract. There is direct evidence of a barefaced lie, which caused such a strong indignation among the Academy leaders.

At first glance, Gmelin’s misconduct is obvious. But would we still blame him if we considered his motivations?

To do this, we have to look back to the moment of his arrival in St. Petersburg. In 1727, when he arrived in the young Russian capital, he was an eighteen-year-old unknown young man, who had just defended his thesis in medicine in the Tubingen University. It was not a surprise that Gmelin did not get an established post at the Academy, whose members were such great scientists as Bernoulli and Euler. What was his reaction? Нe did not despair and did not leave. His friend and outstanding Russian historian and ethnographer G. F. Mueller recalled, “Since he arrived in St. Petersburg at his own expense, he did not ask for a salary. He had an intent to be a freelancer until he found a way for applying his potentialities.” Gmelin fulfilled his intent working as a volunteer at the Cabinet of Curiosities (Kunstkamera) and dealing with some other everyday tasks. The Academy did not leave the young scientist to the mercy of fate, he was paid ten rubles a month “to compensate for the necessary costs” and granted lodging and firewood in winter, which was not too bad, considering that Academy members were paid fifty rubles per month. But this situation could not be regarded as very good either.

This lasted for more than a month or two, for more than a year, this lasted for three years six months! This proves that Gmelin cannot be accused of an extreme mercenariness. Neither can he be accused of self-interest. Let us keep this in mind. After his return from Siberia, Gmelin was at odds with revengeful, quarrelsome and mean-spirited I. D. Schumacher, a power broker at the Academy at those times, and one of the points was the money. Schumacher claimed that Gmelin’s demands were not corresponding to his rank. But first these were the academicians (not Gmelin himself) who wished to eliminate injustice and interceded for him. Second, they requested only to raise his salary to the level of his colleagues who were elected Academy members the same year. Thus, it seems that this dispute was somewhat far-fetched and anyway was not of primary importance.

But let us proceed in chronological order. In 1731 Gmelin was appointed to a professorship in chemistry and natural history, two and a half years later he started on his journey to Siberia as a member of the Academy team of the Kamchatka Expedition. The decision to join the expedition characterized him as a brave person who was utterly devoted to science. He had a chance to resign the trip to “the unknown” — six months before the trip Gmelin was taken ill with an almost fatal sickness; his candidature was replaced by G. F. Mueller. But after the recovery (the story is that one night he desperately drank two bottles of good Rhine wine and woke up healthy the next morning) he insisted on his participation in the expedition, from which many of its members did not return, having found “eternal peace” in the stern remote parts of Russia. Would it be fair to say that Gmelin was searching for easy ways and peculiar profits in his life? The answer is “no”.

Gmelin wrote, “We undertook this long and difficult journey because we were striving to see new places”. Further he described how petty troubles accumulated to affect the mind first and then the body. In his opinion, Mueller’s illness was caused by these factors. “My mind was less sensitive. As a result, I could resist the difficulties longer and at least did not experience any physical injuries. However I could not estimate how long my resistance would last”.Indeed there were plenty of difficulties: annoying delays, misunderstanding and Bering’s tendency to authoritarianism, obstacles put in the way by some Siberian high-rank officials, and many others. A real trouble was a fire that broke out in Gmelin’s house in Yakutsk in 1736 and destroyed the materials gathered over a year.

It is not a surprise that in 1737 Gmelin and Mueller asked permission to return to St. Petersburg. Of course, the four years of travel across immense and undeveloped territories with minimum conveniences and permanent danger could crush anybody. But the willingness to leave was equivocal. Gmelin submitted the application, but on the other hand, he was afraid of obtaining the permit to leave. As he put it himself, “It was such a pleasure to find new plants, which happened every day, and before forwarding the petition I often hesitated if I should take it back, since at the sight of every new plant I had a fear that this joy could soon be put an end to by an impending permit…” Does not this hesitation characterize him as a true scientist and a sympathetic person?

However his fears turned out to be idle: the petitions were strolling for two years in chancelleries and only in 1939 (after six years of wandering across Siberia) Gmelin and Mueller found replies to their petitions, having come back to Yeniseisk from a scientific trip to Mangazeya and Turukhansk. Mueller was allowed to come back to the capital, while Gmelin was ordered “to hurry up his departure to Kamchatka”.

This decision brought Gmelin to a true nervous frustration. In his Journey he found courageous words to express laconically the “sad effect” of this verdict. The effect was caused by fatigue, common offence, demand for normal human conditions, eager desire for systematization and analysis of the enormous materials collected, and homesickness… Glemin applied to Baron I. Korf, President of the Academy (under Tsarine Anna Ioannovna the head of the Academy was officially called “chief commander of the Academy of Sciences”), “If considering the abovementioned, I am still ordered to stay till the end of the expedition, I shall consider my further stay in Siberia as nothing else but an exile, which I truly have not deserved over the six years of difficult trips and for my exploits and good turns in St. Petersburg…”

After this appeal, the authorities ceased to insist on his mission to Kamchatka, nevertheless he was not allowed to return to the capital. Gmelin spent three more years in Siberia. One could hardly reconstruct the state of his mind during these years, but obviously he was not very happy. Probably the decision to leave Russia was made at that time. He decided to leave immediately after his return to St. Petersburg, the permit for which was signed in summer 1742. Already in winter 1743 the scientist reached the capital and nine months later he handed in his resignation from the Academy.

Let us repeat that resignation was a usual procedure, by that time several academicians had been discharged with honors and awards. But Gmelin was not allowed to go. His application for resignation was backed by solicitations to the Senate signed by other academicians (“Owing to frequent illness he needs to change the climate and come back to his homeland”) — without success. Schumacher who took a dislike to Gmelin did not provide him with a copyist, oppressed him by not raising wages, abused him in public by calling him a “sinful and impudent liar.” In this conflict, Count K. G. Razumovsky, a new President of the Academy, took the part of Schumacher, steadily considering Gmelin’s complaints as groundless. The life in St. Petersburg got unbearable and desperate.

Finally, in January 1747, the decision on Gmelin’s resignation was taken, but six months later he signed a new four-year contract, which allowed him a one-year half-paid leave abroad. The reason for the inconsistency is not clear. Later in private communications (immediately denounced to Schumacher through his German correspondents) Gmelin stated that otherwise he would have been forced to stay in Russia.

By the way, Schumacher had visceral suspicions and tried to turn the situation to his advantage. By hook or by crook Schumacher forced G. F. Mueller and M. V. Lomonosov, his opponents at the Academy, to sign guarantees for execution of the contract. In case of breach of the contract, they had to be penalized, besides their reputation would have been damaged. Roughly speaking, Schumacher tried to expose them.

Gmelin left never to return from Germany. In August 1748 he briefly informed K. Razumovsky about the fact that the Duke of Wurtemburg approved his appointment as professor of medicine at the University of Tubingen with no solicitation from his side.

Everything was too obvious. A storm broken out in St. Petersburg resulted in the condemnation of Gmelin’s behavior as an “indecent act” and they required him to return immediately. To take measures against Gmelin the Academy sent letters to G. Kraft and L. Euler who left St. Petersburg several years earlier. As Honorary members granted pensions by the Academy, they nolens volens had to fulfill the Academy orders. Euler tried to fence Gmelin off gently, “I believe that such a flightiness of Mr. Gmelin is caused by lack of prudence, therefore, I would avouch that he had no intent to insult the Academy…”In the same letter Euler mentioned Gmelin’s fiance who refused to move to St. Petersburg… The fiance was pure fiction, a white lie.

Finally, after an intense exchange, Euler was informed that Gmelin should beg the pardon of Count Razumovsky and shift the blame to G. F. Mueller (the latter was not named directly, but could have been readily recognized, which was another plain intrigue woven by Schumacher). Gmelin apologized but did not blame Mueller. Then the affair was hushed up, Gmelin was granted Count’s pardon on conditions that he should finish the five-volume monograph Flora Sibirica and submit it to the Academy. This happened in summer 1750.

Thus, there was a lot of hot air and an appearance of decent relations was observed, but this was only semblance, because anything done by Gmelin since then was accepted with cold distrust in St. Petersburg. Though this issue was pulled to pieces by third persons, the true reasons for his escape from Russia Gmelin explicitly formulated in his letter to Euler. “Recognizing my mistake, I will prove that I deserve the pardon by thorough processing of the materials that will please His Grace (Count Razumovsky — A.P.). What cannot love for their country do? What heart can resist the requests of beloved mother and sisters? My love for my country has no bounds. I hoped that this feeling would ease in a year, but it grew stronger, while I hoped it would sooth. Finally, a grave disease and subsequent decease of the local professor of botany opened a profitable position for me…”

This sounds logical and humanly understandable. The combination of incongruous emotions, romantic lofty love to the motherland and respect to family values with the profit of the position available after the death of the predecessor, testifies to the frankness of these words. Considering all these circumstances, shall we blame Gmelin for the improper, but forced and well-motivated behavior? The question is rhetoric.

But the story did not finish at this salving and reconciling note.

A year later Gmelin published his Journey across Siberia in Goetingen. After all, the St. Petersburg Academy apriori could not regard the book otherwise than with supreme suspicion. The Academy Chancellery even issued a decree: Lomonosov and Mueller were obliged to make a written analysis of the monograph. The order suggested a tendency for the review: “to reveal excessive, obscene and dubious descriptions”. We do not know anything about Lomonosov’s reaction. But we know that Mueller refused to do the review, explaining the refusal by his misgiving that both the praising and the criticism will be interpreted wrongly to somebody advantage. He concluded his repudiation by the words, “what I personally wished to tell about Siberia, I have already submitted to the archive files…”

To tell the truth, according to the standards of those times, Gmelin’s book contained plenty of the “excessive, obscene and dubious” appraisals. He was and still is reproached for harsh attitude to the Russian people and for mocking judgments on national culture. He explained the encountered difficulties by the crudity, laziness and drunkenness of Russians... God knows what other accusations can be brought against his book! But first, all these do not play the key role and, at any rate, are not the main substance and emotional content of the book. Second, Gmelin tried to be absolutely honest (even in his mistakes). Who will dare to say that none of these has ever happened (and may be even oftener nowadays than two hundred fifty years ago) throughout our vast expanses? Third, one should remember about the common frustration experienced by the scientist during the last years of his stay in Siberia. Fourth, people often recognize manifestations of his derisive character as deliberate treachery and slender, while he seemed to be born with an ironic smile on his lips… And finally, all national apologias (in particular, self-apologias) are doubtful, smug and suspect…

However, Gmelin was not concerned about the St. Petersburg grumbling. In the early 1950s his health was failing, he passed away in 1755 at the age of 45. This untimely death might have been caused by the ordeals he had underwent in the Siberian trip. Gmelin’s widow mentioned these reasons in her petition to Empress Elizaveta “May I hope for the mercy of the most August of the Empresses that the widow and children of her servant who spent his forces and talents on official business to the Russian Empire will take advantage of the charities that were meant for him unless the death would steal him in the middle of his studies…”

The charity was deigned. In 1757 the Academy bought Gmelin’s herbarium and paid his widow six hundred rubles. Earlier the materials that belonged to the Academy and his drawings for the 4th and the 5th volumes of the “Flora Sibirica” were brought back to Russia.

This story really happened in the middle of 18th century with an outstanding scientist, German and Russian at the same time, and his books, including the wonderful diary-style Journey across Siberia, fragments of which are published above.