Platonism and the World Crisis

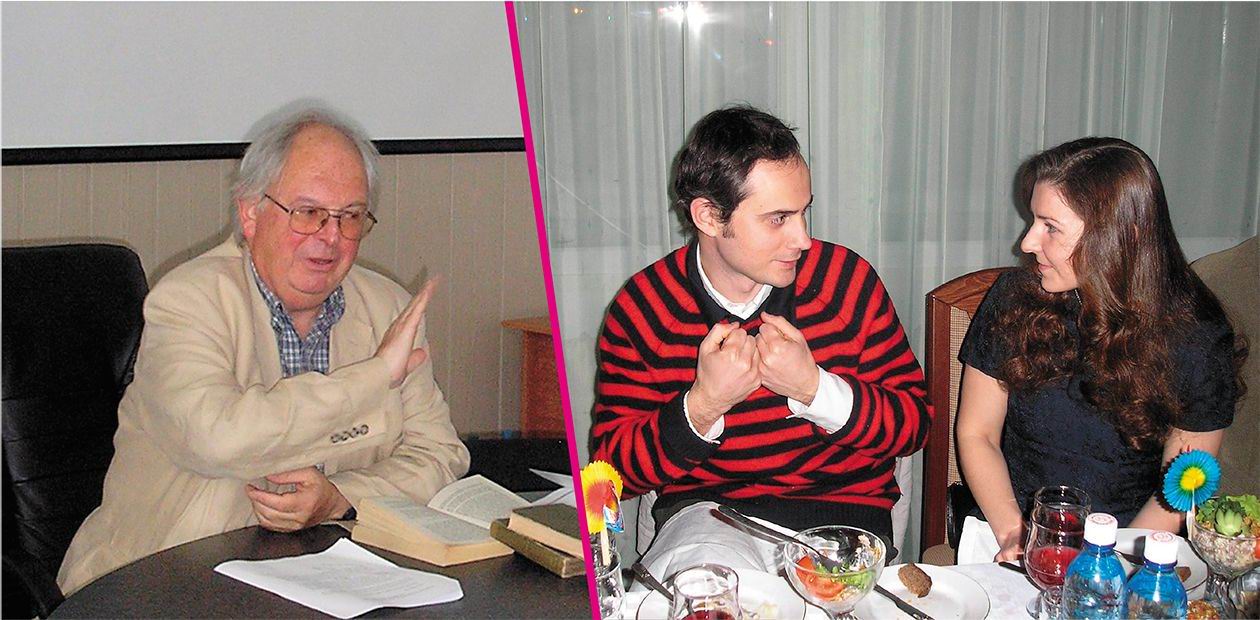

Well-known philosophers, specialists in classical philology, and a group of junior lecturers and researchers from universities of Eastern Europe and Eurasia discussed ancient philosophy and contemporary problems of classical education at two sessions of the interdisciplinary Seminar “Teaching Classics. Fundamental Values in the Changing World”, organized in Novosibirsk Academgorodok in August 2007— and February 2008

It is in fact my deep conviction that Plato, and the tradition deriving from him, has a number of important things to say to the modern world, and the modern world will do well if it listens to them. Of course, Plato had no conception of the nature or complexity of the issues which modern civilization is currently facing, and nonetheless, it seems to me there are many useful insights which we may derive both from his own works—in particular, his last great work, “The Laws”—and from those of certain of his followers, in particular, Plotinus (Dillon, 2007).

With these words Professor John Dillon, President of the International Platonic Society, a world-known philologist and the historian of philosophy from Trinity College, Dublin, whose numerous works are dedicated to Platonism and the Platonic Tradition in its various aspects (cf. Dillon 1996 and 2003), opened his lectures in Academgorodok.

Dillon has chosen three subjects for discussion, which, according to him, play a key role in the contemporary situation and explain how the seemingly abstract ancient philosophy could contribute to the solution of the most important problems of modernity. They “represent the great bulk of what is wrong with modern western society, and what is inexorably putting intelligent life on this planet under mortal threat”. The problems are the following:

(1) The problem of the destruction of the environment and of waste disposal.

(2) The problem of religious conflict and mutual intolerance.

(3) The problem of legitimating the authority and the limits of personal freedom.

According to Dillon, on each of these questions Plato has things of importance to say, and the modern world would do well if it listened to them.

The world sub specie aeternitatis

The contemporary society begins to realize, though slowly, that the root of our problems related to the destruction of environment and its pollution is the modern concept of progress as “a linear development upwards and outwards in all areas of society”: we need more plants, more public facilities, and a better ‘quality of life’, which, in fact, means that we are consuming more. It is clear, however, that this cannot last for long—enormous members of the emergent world like China and India can turn the planet into garbage dumps simply by seeking to emulate the level of consumption in the United States and Western Europe.

The modern man cannot imagine a society where no concept of progress is present, and therefore all suggestions designed to overcome the crisis proposed so far involve the same concept of “development”, only in the “right” direction. Now let us imagine a society where a linear development and constant change are not considered the basic values. Plato and his contemporaries saw the same phenomena we do now: they observed nations’ and societies’ ups and downs, empires rises and falls; technological advances and degradation of moral standards, etc., but never (with a few exceptions to the rule) evaluated all this in terms of progress or regress.

It was universally accepted in pre-modern cultures that change in the physical and human world was cyclical, not lineal, while Platonists proposed a radically new world attitude — they explored each visible phenomenon from the aspect of eternity, “sub specie aeternitatis”, seeking for the essential nature of things—those fundamental values that Socrates was indefatigably looking for in Plato’s dialogues.

What, according to Dillon, “Plato is presenting for our scrutiny is a strictly regulated ‘steady-state’ society, designed to secure both internal harmony by reason of justice of its political and sociological arrangements, and harmony with its natural environment by ensuring that the demands it puts upon it do not exhaust or distort that environment”. Then, having taken his country, Ireland, as an example, he explicated the Platonic concept of the ideal state in some details, including the mechanism of achieving a reasonable balance between the number of inhabitants and the resources available in the country for supporting its population.

The vexed issues of nationalism and religious intolerance provoked in Plato’s time as heated debates as they do nowadays. The Platonic approach to this matter can also teach us a good lesson: having developed in the Republic and the Laws a specific form of philosophical religion, he nonetheless exhorted the citizens to perform traditional religious rites—both for cultural and political reasons.

The Platonian religion knows no religious conflict. Let us, following Plato, allegorize our beliefs and “agree to differ”: each religion goes its own way and none of them is better than another.

On a Democratic Paradox

In the age of a crisis of the concept of liberal democracy it is interesting to look at the roots of the problem and listen to the man who lived in the epoch of rise and fall of Classical Athens — in a sense, the “archetype” of all future democracies.

In Book VI of the Republic Plato employs the striking image of the “Ship of Fools” as an illustration to his criticism of the democratic state. The ship is governed by people who have no idea how to steer the vessel and their “knowledge of naval matters is limited”. Consequently, the ship permanently experiences shipwreck, changes direction or gets lost in the sea. Quite naturally, the captain loses support of the crew and is “thrown off the ship”.

On the other hand, attempts to establish a “controlled democracy” lead to usurpation and, consequently, an equally fast and disastrous collapse of confidence in the authority. Plato perceived this paradox of democracy as clearly as Jefferson or Churchill, and his suggestion, which could appear too simplistic at the first sight, is the following: neither the direction in which the ship moves nor the steersman matter as such; what really matters is education (paideia), that moral and intellectual training which all the citizens share and which should begin in the mother’s womb.

Besides, insists Dillon, everybody, men and women alike, should participate in a system of National Service, viewed as a mechanism for initiating young people into adult life; and if one refused to take part in this service, he or she would no longer be considered a citizen of the state.

Suggestions proposed could, perhaps, appear too extreme to the readers, but, as John Dillon notes, “the situation that the human race as a whole currently faces is so serious that a seismic shift in our ethical consciousness will be necessary”. Therefore, it is reasonable that humanity prepares itself to the future shock now and restricts consumption to the real necessities before it faces more disastrous problems.

Although, admittedly, Plato lived in the world quite alien to us, and the situation in Ireland is different from this in Russia, Dillon has apparently managed to convince his audience that the Platonic tradition “has a number of important things to say to the modern world, to which the modern world would do well to listen”.

From Cambridge and Teheran

After Dillon’s lectures on Plato’s Laws Prof. Leonidas Bargeliotes, President of the Olympic Philosophical Scociety (Athens-Ancient Olympia), gave the course on the tradition of the classical education and Prof. Mostafa Younesie (Teheran) presented to the listeners his approach to the theory of “intercultural thinking”.

The winter session of the seminar (January—February 2008) included further discussions of the topical problems of the classical studies and a round table on ethics, led by the world famous historian of ancient philosophy, Professor Emeritus John Rist (Cambridge) and Dr. Teun Tieleman (Utrecht). For details see the publications and web resources listed below.

Future Plans

The organizers and participants of the seminar are expecting to initiate a number of collective educational and research projects. New materials will be made accessible to the junior university teachers and students in various fields of humanities; new curricula and scholarly publications will be prepared and a new international society established, which will lay the foundation for the future productive cooperation of the Western scholars, regional faculty, and advanced graduate students. Participation in these activities will become an important step towards the professional carrier for young scholars and university educators involved in the project.

It is essential that participants be committed to work as a group for an extended period of time, have a clear understanding of their responsibilities and mission as educators, and be able to formulate their educational strategies and philosophy in teaching classics.

The main justification for this work would be achievement of a real collaboration within the team. This would allow to look at our problem from various perspectives and to apply the approaches originating from different traditions in order to reach mutual understanding and cooperation. We expect that the dialogue will be fruitful and enrich our knowledge of the Classical Tradition and its connections with such important issues as changing values and multiculturalism critical thinking.

References

Dillon J. Platonism and the World Crisis // ΣΧΟLΗ—2007— N 1.1.—P. 7—24

Dillon J. The Middle Platonists, B.C. 80 to 220 A.D. Ithaca, N.Y., 1996. Dillon J. The Heirs of Plato. A Study of the Old Academy, 347–274 B.C. Oxford, 2003.

Rist J. Plotinus: the Road to Reality. Cambridge, 1967.

The Centre for Ancient Philosophy and the Classical Tradition: http://www.nsu.ru/classics/

Interdisciplinary Seminar “Teaching Classics. Fundamental Values in the Changing World”: http://www.nsu.ru/classics/reset/index.htm

ΣΧΟLΗ on-line: http://www.nsu.ru/classics/schole/index.htm