Physicist and Biologist: High Energy Pair

“...The science school of Novosibirsk gave birth to many talented physicists, who now have dispersed around the world yet maintain very close contacts. Graduates of the NSU Physics Department are now working at Fermilab, SLAC, CERN, Oxford... This connection is global, and it works. One can call the Novosibirsk school the global accelerator alma mater. This network has a huge impact on the global accelerator science. I am proud that I belong to this cohort of people who are connected with one another and with Novosibirsk State University...”

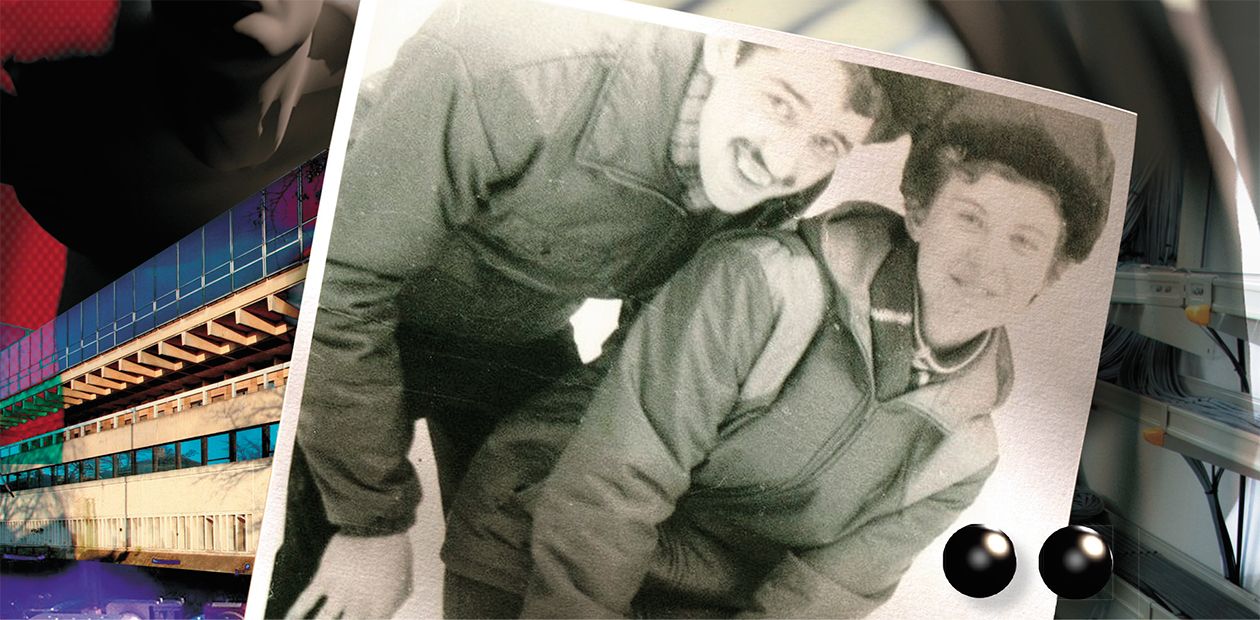

In an interview to SCIENCE First Hand, Andrei Seryi, graduate of the NSU Physics Department (1986), Director of the John Adams Institute for Accelerator Science (JAI, United Kingdom), and his wife, Elena Seraia, graduate of the NSU Natural Sciences Department (1986), Research Assistant at Oxford University (United Kingdom) told us about their scientific career and how it was influenced by Novosibirsk State University and the first love...

Today, Andrei Seryi and Elena Seraia are living in Oxford. Andrei Seryi is the director of the John Adams Institute for Accelerator Science; Elena Seraia works at the Department of Medicine, Oxford University. However, their long scientific journey Kemerovo (Russia) – Novosibirsk (Russia) – Protvino (Russia) – Rambouillet (France) – Protvino (Russia) – Chicago (USA) – Stanford (USA) – Oxford (UK) has not ended yet: “We have the feeling that we are cosmopolitans,” says Elena, “our home is where we keep our suitcases. We used to say that our home is where our kids and cat are, but now our kids have grown up and live in California, and we are citizens of the world. Our home is where we work, so I cannot say that we have settled anywhere.”

What has led a boy from a miners’ settlement in the suburbs of Kemerovo to the Big Science?

Catch up and overtake

Until the eighth grade, I went to school in the miners’ settlement Yagunovka; my father was a chief engineer at the Yagunovskaya Mine. There was only one school at that small village, and the level of physics at the school left much to be desired. One day my brother showed me a newspaper from which I learned that School 1 in downtown Kemerovo was recruiting pupils to a physical and mathematical class. Without hesitation, I went there to sign in.

When I first came to the new school, I saw on the board of honor a photograph of a girl who I really liked, and then we happened to be in the same class... The first months at the school were really tough: I had to catch up with the classmates. I was close to getting a “three” (“average”) in physics in the first semester, but I finally managed to make a “four” (“good”). All the ninth grade, I was studying like mad and, on top of that, had to commute from Yagunovka to the city. By the end of the school year, I caught up and outdid all my classmates and, later, in the tenth grade, won a regional competition in physics. Apparently, at that time I decided that I was “eligible” to approach such an excellent student as Elena Lebedinskaya. Although there were a lot of contenders for her heart, we were sitting at one desk by the end of the tenth grade.

One day Lena asked me where I wanted to continue my studies after high school. I was thinking about Moscow—Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Moscow Engineering Physics Institute, or Moscow State University, but Lena wanted to study only at Novosibirsk State University, at the Natural Sciences Department. At first, her mother (Elvira, aka Lira Kaminskaya, then Lebedinskaya) was a student of the first intake at the NSU Physics Department, and, second, NSU had a very strong background in genetics, which was the most important thing for her. I thought, let it be Novosibirsk, why not? We would go together, and that was the most important thing for me!

Raised by the global accelerator alma mater

I was so worried before my first entrance exam that could hardly sleep. However, I got a “five” (“excellent”) at the first exam and was enrolled “automatically,” without having to take the other exams.

At that time the chairman of the admissions board was Nikolay Dikansky. He then was a very energetic man, always wearing a denim jacket. Someone from the dean’s office ran up to me, when I was sitting on a bench near the university and reading a sci-fi book, and asked:

– Are you Seryi?

– Yes, that’s me.

– Let’s go to the dean’s office, we’re going to enroll you at the university.

At the dean’s office I saw members of the admissions board and secretaries sitting there and drinking tea with condensed milk. They also offered me a cup of tea, and Dikansky began to ask me questions about how I solved the problems at the exam, what my plans were and if it was true that I wanted to become an academician. I don’t know how he knew about that, but I confirmed. I gathered that it was a “microinterview.”

I came to understand that I wanted to do physics related to accelerators at an age of 13 or 14, when I read a sci-fi book by Valery Agranovsky about the discovery of element 104 of Mendeleev’s Table. This element was discovered in Dubna almost simultaneously with US scientists, but recognition for making the discovery was attributed to the Americans. I was so fascinated by this sci-fi detective story, that I decided to do something like that. However, in my dreams I had a highly incorrect idea of my future job: an office with pine trees (a necessary element) outside the windows, I’m sitting at a desk and thinking… So romantic!

ANDREI BELYI…

THAT’S WHY I CALLED HIM ANDREI

In fact, I tried to persuade him to go to Kemerovo Polytechnic Institute. I did not want him to leave, but he did not hold this institution in high regard.

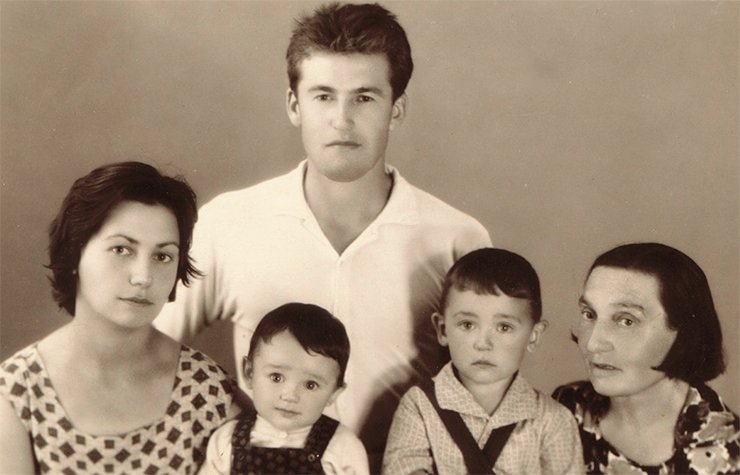

He learned to read at a very early age and took interest in everything! He wrote letters to the editors of the magazines Modelist-Konstruktor (‘Model Designer’) and Yunyi Tekhnik (‘Young Technician’) and received their answers. Since he was seven, he traveled from Yagunovka to the city center to a shop called Yunyi Tekhnik.

When he began to read, he did it upside down. While their granny was reading them fairy tales, he was following the text. That was how he began to read; later we had to teach him the right way.

But this does not mean that he was reading books all the time: he spent days outside with his brother and his dog Ryzhik, they ran down the fields, caught susliks, skied, climbed trees, jumped from the roof down into the snow… it is so good that we did not know about that.

When Andrei was 11 years old, we bought a car, and he immediately began to steer, although one could hardly see him from behind the wheel.

He and his brother were tinkering with something all the time. The older son was always inventing guns, and Andrei was fond of wood carving and building model airplanes. Once he gave me, as a present, a very beautiful carved box, and I still keep it in our home.

The idea of my future job finalized during my university studies. In the first year we had lectures on electrodynamics by I.N. Meshkov. He personally selected the best students and sent them for practical training at different laboratories of the Institute of Nuclear Physics (INP). I was assigned to a lab focused on electron cooling, which was led by Dikansky. My immediate supervisor was Vasili Parkhomchuk. He greeted me, a freshman, showed me the lab, and, as early as in my second year of studies, I spent a couple of days a week working at the institute.

The research conducted by the INP electron cooling group was at the forefront of the world science. So, since my second year at the university, I began to work with world stars: the people who developed this method, demonstrated it experimentally and applied it to real-life projects. It was an unforgettable experience! This training was highly motivating and helped me come to the world level in science. I have always wanted to reach the level of such masters as Parkhomchuk and Dikansky. This bar, which was raised as early as in my student days, I have not yet reached, but I have a goal to strive for.

Elena and I got married when we were in our third year of university studies. Two years later we graduated from the university; Elena began working at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics and entered the postgraduate program to defend a candidate-of-sciences dissertation; I stayed with the same laboratory at the INP. In 1988, the institute announced a call to build a linear collider in the science town Protvino. There were construction works underway to build an accelerator-storage complex (the tunnel had almost been finished). An idea came up to also build a linear collider, and the most part of the laboratory staff, including Parkhomchuk, decided to go. We did not evaluate the prospects at that age: it was exciting, my friends were going, so I had to go too...

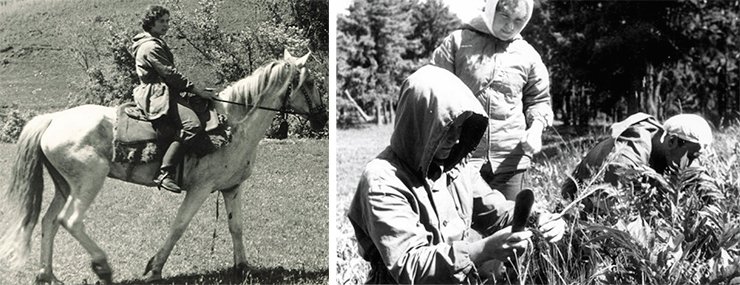

“I KNEW SINCE THE SECOND GRADE THAT I WOULD WORK IN SCIENCE AND BE A BIOLOGIST…”“The funniest part of these studies was when Pavel Borodin was collecting information on cat genetics. I arrived in Novosibirsk, at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics, to meet with Anatoly Ruvinsky. He gave me a map on which I was to put a mark indicating the exact frequency of a particular feline gene in the neighborhoods of Kemerovo.

“There were no stray cats in Kemerovo in 1980; so we went with Andrei to the suburbs, to a settlement near the Pionerskaya Mine, where our classmate lived. In fact, this was a village where there was a cat in every private house. We were very lucky that everyone in the village knew our friend because in that year, a tax was imposed on cats and dogs. We were collecting information about cats, but the people got scared, thinking that we were collecting money. We reassured them: ‘You see, we are asking neither the name nor the number, just show us your cat, please, that’s all!’ It was absolutely crazy! But we collected really good material: 130 cats. There were about 12 mutations on the list. Then I calculated the frequency of the genes, put the figure onto the map, and brought the map to Novosibirsk. These data were included in Borodin’s book”

Leaving Novosibirsk was not an easy decision. First, our elder daughter Eugenia had just been born, and, second, Elena was at the stage of deciding on the theme and objectives of her dissertation, and it was difficult for her to leave the job that she loved. This held us back, but when we saw that the core members of my group were leaving, we decided to go.

We worked in Protvino for a fairly long time. There our second daughter, Sasha, was born.

In 1994, a colleague from France invited me to work for several months at a laboratory of the Saclay Nuclear Research Center near Paris. At that time I was engaged in research on collisions and beam focusing methods. Eventually, we spent two years In France, in the town of Rambouillet. Elena learned to speak French; the kids went to school and kindergarten, and talked fluently in French.

In 1996, we returned to Protvino, and two years later, my friend and colleague Vladimir Schiltsev, with whom we worked together at the INP, invited me to take part in an exciting project run by Fermilab in the United States. This is how we found ourselves in Chicago, with our kids and a Siberian cat.

Multidisciplinary union

At Fermilab there are a lot of physicists from Russia, including from Novosibirsk, over a dozen people. We even called it jokingly an INP branch. One day, sometime in 1998, we decided to set up an international community of friends of Novosibirsk State University and raise money for scholarships. Everyone was excited about the idea. Elena and I decided to encourage natural science “unions” and establish a scholarship for married couples one of whom is a physicist and the other one is a biologist and who show high academic performance. Indeed, a union of a biologist and a physicist can be very rewarding. There was even a joke at the NSU Natural Science Department: “Mathematicians study math; physicists study math and physics; chemists study math, physics and chemistry; and biologists study math, physics, chemistry and biology.”

When I entered the Natural Sciences Department, the beginning of the first year was also funny: all the departments were sent to a kolkhoz to harvest potatoes, but we worked at a vegetable warehouse in Kainka. In the morning, we attended lectures on botany and physical chemistry, and in the afternoon we worked at the warehouse, unloading cars and sorting the potatoes harvested by students from the other departments!

“The potatoes were brought to the warehouse, and we were sorting them in any weather. When it rained, the conveyor was giving strong electric shocks to those who did not wear rubber boots”

We discussed this idea in the association and sent a letter to NSU, but, to be honest, we thought that they would treat our idea as a joke. However, the university authorities were serious about our proposal, and soon there were six couples that met the scholarship criteria. Later, some of the couples wrote us letters of gratitude and sent wedding photos. However, we did not want to interfere with their private lives and never replied to those letters. The project continued for about seven years; then the situation at NSU began to improve, and, at some point, the project was closed.

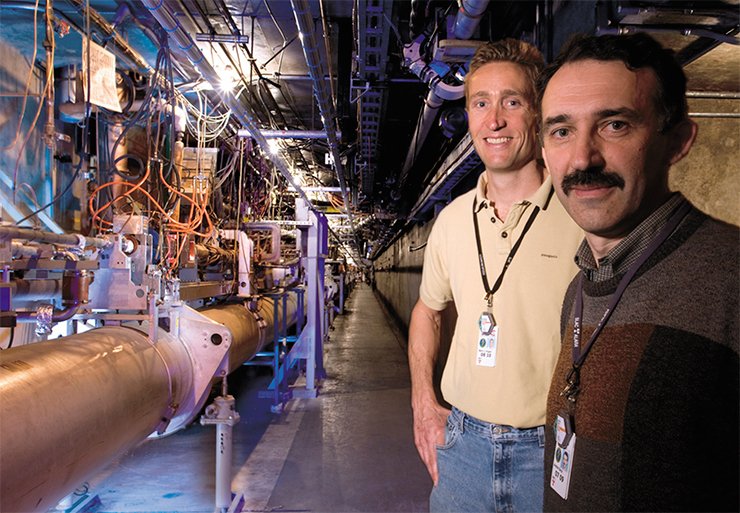

We worked for about two years at Fermilab. I was engaged in the development of a facility to compensate the effects of beam collisions at the Tevatron collider, a circular particle accelerator; Elena took part in the development of a new system of silicon detectors for the collider. Then I was invited to the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC).

We worked for 11 years at Stanford. I was engaged in designing a linear collider and also in developing the plasma acceleration experimental facility.

Elena worked for over ten years at the Stanford Functional Genomics Facility. Although she had no PhD degree, but only the MSc degree from Novosibirsk State University, the head of the facility believed in her and gave her a job, and he never regretted doing that.

60,000 GENES ON ONE MICROSCOPE SLIDE!When we were leaving for Oxford, the head of laboratory at the Stanford Functional Genomic Facility, with whom I had worked for 11 years, said, “I was so happy every day that I hired you blindly because, for more than ten years, you’ve been a key member of our laboratory.”

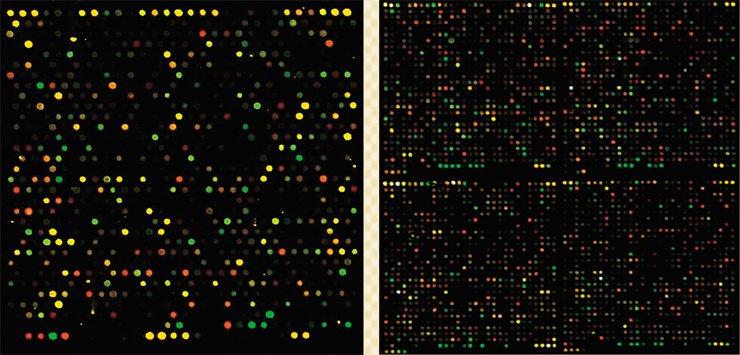

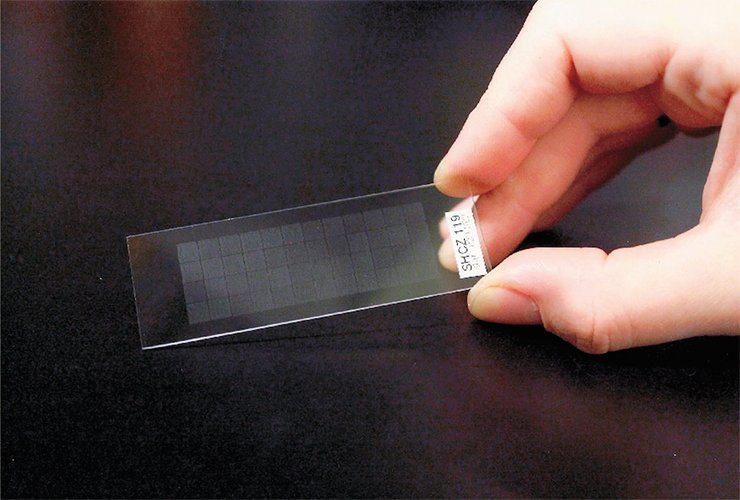

We printed microarrays, which allow researchers to analyze the expression of thousands of genes simultaneously on a single glass slide. The microarray is a 1x3 inch microscope slide carrying “pieces” of double-stranded DNA or oligonucleotides, each of which is a separate gene.

We had to print about 60,000 genes, i.e., 60,000 points with a diameter of 50 microns, on one slide. I was working on a technique how to do that with a high print density (at first we printed only 28,000 genes on one slide). Our work was successful, and we were selling the microarrays to 26 universities in 15 countries.

We had a library of genes, i. e., pieces of DNA that are built into plasmids. To “replicate” these genes, we conducted a polymerase chain reaction for each piece of DNA, made solutions of a required concentration, and printed the gene library on the slides.

If we add to the denatured DNA fragments printed on a slide the patient’s DNA sample (prepared from mRNA) and the control normal DNA (marked by different fluorescent dyes), then the complementary fragments are hybridized.

Thus, we can reveal in a patient the expression of a gene that is normally not expressed. We marked the control normal RNA/DNA with, e. g., a fluorescent dye that gives a green color when applied to the specimen, and the patient’s RNA/DNA, with the dye that gives a red color. Then we applied the two samples on a microarray, scanned the glow in the red and green regions, and superimposed the results (which gave a combination of different shades of yellow). If a given gene worked in a cancer patient, the sample contained a lot of the corresponding mRNA/DNA, which got bound to the DNA on the slide, and we saw red glow. If the patient’s gene did not work, it was only the green-glowing control normal DNA that got bound with the microarray. If we saw a yellow point, it meant that the gene works, to some degree, in both cancer patients and in normal cases.

The robot was printing the microarrays for four and a half days without stopping, 255 slides per cycle. I was responsible for preparing the printing material (125 plates with 16x24 “wells”), starting the process, and organizing the work of the laboratory technicians. If there were problems with the robot, I was called to the lab day and night.

We were the first in this area. There were only five people on our team. Later on, after a few years, this area attracted the attention of large companies, such as Agilent, which assigned hundreds of people to this issue.

Businesses took up the idea and developed new microarray technologies, e. g., for growing oligonucleotides directly on the slide in the cells of a special grid, print samples by the inkjet printer method, or apply them on tiny beads.

However, our glass slides went to academic institutions because they were inexpensive. One microarray cost $130 while those produced by commercial companies cost about $1000. Therefore, universities from the United States to Singapore were using our glass slides.

However, her love for genetics has remained unfulfilled. The decision to abandon her candidate-of-science dissertation and go together to Protvino came at a cost of her academic career, and we knew it. I have always said that Elena is a Decembrist wife, except that they followed their husbands to Siberia, but Elena followed me around the world. Nevertheless, she is an excellent specialist and always finds a job in biology or medicine. There are professors who write research papers, and there are people without whom they cannot do that, i.e., those who prepare and conduct experiments and collect material for research work. Elena compares herself with Gosha (an indispensable golden-hand technical professional behind many scientific experiments) from the film Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears.

From the Wild West to Oxford

If anyone had told us that after working for 13 years in the United States, we would move to the United Kingdom, we would have never believed that. However, the feeling that one is “settled” may appear only when everything is done and all problems are solved, but until then, everything is possible.

So, we moved to Oxford. In the United States, I worked at a large laboratory that was focused on basic science; applied problems were a secondary issue. At Oxford, everything was different: the first priority was to think how to implement a scientific idea and how to move from an idea and its experimental demonstration to specific applications, e. g. in medicine or business. I had to think about it all the time; moreover, one third of the institute funding came from grants, projects, contracts, cooperation with companies, etc.

One of these approaches is the Theory of Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ). It was developed by Genrikh Altshuller in the Soviet Union in the mid-20th century. Since 1946, Altshuller, who worked at the patent office, had analyzed many thousands of patents in an attempt to identify the key points that make a patent successful (this work was interrupted for a decade because of dramatic circumstances in his life, but he managed to survive the hard times, find an unexpected opportunity to get a broad education and resume his studies). Between 1956 and 1985, he formulated the TRIZ algorithms and developed this theory together with his team. Gradually, this theory has become one of the most powerful tools in the industrialized world.

I thought that the TRIZ methods can be applied in accelerator science. With this idea in mind, I reviewed the lecture course on accelerator physics that I had been giving for three years at the University of Oxford.

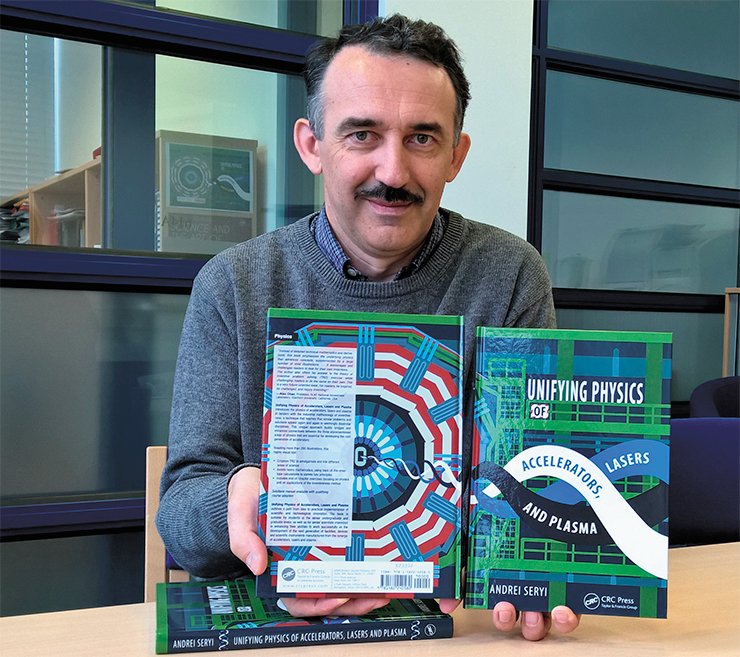

Starting last year, we began to use a new, inventive approach in our lectures. This course was developing gradually and, finally, even changed its name: it is now called in the same way as the book, which will be the main textbook for the course: Unifying Physics of Accelerators, Lasers and Plasma.

I think it is really exciting for students; of course, they have nothing to compare it with since this is a completely new material, but I see that they are truly fascinated by inventive innovations. Moreover, this approach should be interesting not only for students but also scientists from the most diverse fields who wish to expand their horizons.

For us it was very important to translate this book into Russian, so that it would be available in Russian, and each student could buy it, if not at the price of a donut, but at least at the price of a lunch.

We have recently made it through all stages of working with the publishing house URSS, made the last corrections to the text, coordinated the proofs, etc. The book has been released in June of this year. It is interesting to note that the editors from the Moscow publishing house suggested that we change the title so that it would be more “catchy” and better reflect the essence of the book. I agreed with their arguments and came up with a new title: Inventing Instruments for Science of the Future. We also asked our daughter to redraw the cover in a different color scheme: now the spirals are painted in the colors resembling the Russian flag.

Although Russian is our native language, translating the book into Russian was a challenge. We divided between us the odd and even chapters and began translating the text in parallel; however, while Elena was translating consistently and very carefully, I was doing my part from time to time and hastily. So, Elena had to take up my chapters and translate them from my Russian into the literary Russian. In fact, Elena rewrote the whole book; therefore, the Russian book has two authors—Andrei Seryi and Elena Seraia.

The biggest challenge was that the Russian language often does not have the terms that exist in English. In this case, Russian physicists simply pronounce the English words in the Russian manner, e. g., veikfildy for Wakefields. But what sounds good in oral speech, is often unacceptable in serious literature; therefore, we had to put a lot of thinking into it and often introduced new terminology.

While working on the translation, Elena has gained such a profound understanding of the material that she now helps me with everything—with lectures, books and presentations.

She helped me with my lecture at the science festival in Moscow by translating and popularizing the material; sometimes, she acted as a scientific editor by revealing inconsistencies in the logic.

While working on the lectures and the book, we got an idea to write another book that would be more into popular science and cover a broader range of topics, i.e., about inventiveness in biology, chemistry, etc. as well as in the field of laser and plasma accelerators. We discussed the idea with the CRC publishing house, but since it is a very complex task, we will be thinking about it till sometime this autumn.

Frankly speaking, the whole process of writing a book is a big pain. The words do not always flow freely and get themselves down on paper. Sometimes you have to force yourself so that you can “squeeze” out one paragraph a day under a great time pressure: after all, no one is going to do your regular job for you. But later, when you read what you have written, all the pain is paid off.

Then I decided to approach this subject “from afar” and began to explore the process of making inventions and the existing invention methodologies. Apparently, I was driven by my childhood passion for inventions. And very soon I realized that I did not need to reinvent the wheel: the Soviet scientist Genrikh Altshuller developed the engineering methodology called Theory of Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ). I was curious to apply this methodology in science and teaching by “mixing” it with the physics of accelerators and lasers as an ingredient that binds together different areas of science and gives motivation for new inventions. Then I got an idea to develop a university course on TRIZ. I shared this idea with one of my colleagues, a member of the JAI advisory committee of the John Adams Institute, who is in charge of the accelerator science training of under- and postgraduate students in the United States, and he suggested that I should deliver this course the following year. I bought a lot of books on inventions, lasers, plasma, and began to prepare the course. One day a young lady knocked on the door in my office, who happened to be an editor at a publishing house. It turned out that she was looking for my colleague and knocked on a wrong door, but we got to talking. I told her about my course, and she invited me to write a book.

This was the beginning of a big work: first, we have prepared 14 lectures and then began to write a book. Elena was very helpful to me, wrote the part about the DNA damage by irradiation and drew 256 illustrations! Only two photos in the book were taken from other sources; all the rest were made by Elena. And the book cover was created by our daughter Sasha.

The book has already been published in English; we have recently completed a translation, and it has recently been published and now available in Russian too.

What can I say about the Tomsk universities? They have their own specific features: the two very strong universities, whose activities heavily overlap, spend a lot of effort on internal competition instead of the external rivals. In 2005—2009 an extensive analysis was conducted of the potential of the Tomsk Scientific Center, and the experts argued that the combined research potential of the Tomsk universities and research institutes is greater than that of Moscow State University. Science and education is the main goal of the city of Tomsk, as stated in its Charter.

I endorse the merger of Tomsk universities, although I understand that this task is very complicated. There are such trends in the world, e. g., two Manchester universities merged ten years ago. The atomized Parisian universities are also merging gradually. One should not compete with their neighbors; it is better to cooperate with them in order to be competitive on a global level

In the introduction to the book, I thanked the NSU rector Mikhail Fedoruk for the invitation to deliver a lecture to NSU freshmen. I sent him our book, and when there is a chance, we will discuss the opportunity to organize an intensive course “Combining the Physics of Accelerators, Lasers and Plasma” at NSU.

I would love to come for a week or two to Novosibirsk and present this course at our university.

I owe a lot to Novosibirsk State University. It was there that my attitude towards life and towards physics was shaped. The ability to work hard and to build a tight-knit team to work jointly on a large complex project was also shaped at the university and INP. And I am ready, for the best of my ability, to help the university in hard times. I hope that NSU will be developing by an exponential trajectory. We have seen photos of the new building and in July 2016 had a chance to visit it. I think that it will give a new impetus to the university, and the relations between the SB RAS institutes and the university will become even stronger and continue to develop. The graduates who are now working abroad sincerely support their Alma mater.

I am a co-chair of RuSciTech, an association of Russian-speaking science and technology professionals abroad, which is trying to attract the attention of Russia’s government to the problems of science and contribute to the development of science and education in Russia.

I keep saying that Novosibirsk State University is the best university in Russia. I believe that its chances for a leading position among the Russian universities within the 5/100 program are very high, and I think that it should be at the top of the list. NSU has an enormous potential; if it is fully realized, our university will have all chances to be one of the best universities in the world!