Chokhryn-oyka – “Dragonfly Old Man,” “Knife Old Man” – a forest doctor, official, lifeguard

Taiga sanctuaries of a Mansi deity

The Northern Mansi are a large local group of the Ob Ugrians, the only one among the Mansi that preserves the living tracks of traditional culture. Mansi gods and spirits still have an influence on the life of modern population: when a baby is born, it receives its own safeguarding spirit, a personal patron that accompanies the newly born throughout his/her life. Moreover, people constantly encounter the spirits-masters of the surrounding grounds, which mostly function as patrons of trades. Like any people, the Mansi have some special and particularly revered deities. Their “popularity” shows, among other things, in the number of sanctuaries dedicated to them. One of the best-known patron spirits of the Northern Mansi is Chokhryn-oyka, a tutelary of Mansi’s most important occupations: hunting, deer breeding and fishing

Chokhryn-oyka (Sekhryng-oyka) – “Dragonfly Old Man,” “Knife Old Man” – is one of the best-known guardian spirits of the Northern Mansi.

The Mansi believed that in summer Chokhryn-oyka had the habitus of a dragonfly and in winter turns into a man who goes on otter-lined skis. One of the tales describes him as follows: “From outdoors there came in a man all covered with narrow-blade knives, with a silver staff is his hand – it was the Knife Old Man.”

The Mansi believed that there were seven Chokhryn-oyka brothers: one lived in Ust-Tapsui, another in Khalpaul on the Northern Sosva, the third one on the Ob, in Neremovsk yurts near Berezovo, the fourth in Shaininsk yurts lower than Berezovo, the fifth in Kazym, the sixth in Tursunt-paul, and the seventh somewhere lower Obdorsk (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958).

Chokhryn-oyka roles

They believed that all the spirits living on the earth paid tribute to the younger son of the supreme god Mir-susne-khum, and Chokhryn-oyka was the tribute collector. The legends written down by A. Kannisto tell us about another “administrative” function of the deity: the court hearing of guardian-spirits held once over a forest spirit that had stolen a dog from a Vogul authorized Chokhryn-oyka with passing the sentence (ibid. p. 144).

Among the Voguls, Chokhryn-oyka was a well-known healer: he “helped” those suffering from aural diseases. If ears ached and rankled or a person was becoming deaf, they would take a knife, wrap it in a cloth rag and send it to the nearest of the deity’s sanctuaries with an appeal for help.

He also protected all those who happened to be in a difficult situation on the water: “Once the Vogul Lobsinia going in his boat hit a snag – a split formed. He pleaded to his patron, Chokhryn-oyka, and threw a knife to him into the water. The leak in the boat stopped” (Nosilov, 1904, p. 7). According to an informant of A. Kannisto (early 20th c.), in case the boat leaked, one had to wind three tobacco leaves round a knife, fix them with a red ribbon and thrust the knife into the kayak’s cover. Later, this knife should be sent with a fellow traveler to Chokhryn-oyka’s keeper (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958, p. 149).

When they made tobacco, they would also appeal to Chokhryn-oyka: a person would take a cup with tobacco in his hand, lift it up and say, turning it in different directions: “Smell it, Chokhryn-oyka, smell it and make more tobacco! Let it be so strong that everybody who smells it will cry!” (ibid.).

Small Mansi villages are located in the Berezovo region of the Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous District-Yugry on the banks of the river Severnaya (North) Sosva and its tributary LyapinIf a deer was lost in the forest, Chokhryn-oyka was there to help. The master of the house would make three notches on the handle of its narrow knife that symbolized the face (eyes and mouth) of the patron spirit, then he wound a red ribbon around the blade and the handle so that only the tip of the blade showed. This knife would be thrust into the back (sacred) wall of the room and left there for seven days, no matter whether the deer was found or not. At the same time, the deity had to be offered a sacrificial kerchief, money, food, or a bottle of vodka. Cloth and money would be sent to Ust-Tapsui, to the keeper of Chokhryn-oyka’s sanctuary, plus a sacrifice was to be offered to the patron spirit near the back wall of the house: the knife would be forced vertically into the table, next to it was a bottle of vodka and a plate with meat; at the same time they would ask Chokhryn-oyka to bring the lost deer home. If there was no sacrificial table, a bottle of vodka and a plate with meat would be put on the roof of the dwelling (ibid. s. 149–150).

They would also plead to the Knife Old Man for good luck in hunting:

Above the cape, from a lake swan’s eye view,

Above the cape, from a lake swan’s eye view,

Enchanting, with seven knives,

Accepting the bloody sacrifice,

Enchanting, with six knives,

Accepting food as sacrifice!

Your windswept clothes,

Fling them on your shoulders dressed in sable,

Your windswept hat,

Lay it on your head with seven braids,

Gird yourself with a belt soaked with rains!

Your many sons, who have grabbed an arrow, entreat you,

Your many sons, who have grabbed a bow,

Weep and lament in sorrow, calling out to you.

Your Supreme dear father

Made you the power of the earth,

Your Supreme dear papa

Told you with your seven knives

To accept the bloody sacrifice (ibid. p. 151).

By the early 21st century, three sacred places of Chokhryn-oyka worship remained: on the eastern slope of the Urals, at the estuary of the Tapsui River and above the village of Vezhakary on the Great Ob.

Chokhryn-oyka and Ner-oyka sanctuary on Lake Turvat

Lake Turvat (Yalbyn-tur, Yalpyng-tur, “Sacred lake”) lies close to the eastern slopes of the Ural Mountains; the Malaya Sosva flows from here, then runs into the Bolshaya Sosva, turning into the central waterway of the Lower Cis-Ob region – the Severnaya (North) Sosva. The appearance of Lake Yalping-tur belongs to the earliest events of the Mansi mythological history and is connected with the legend of the Earth’s origin. The Mansi believed that the Ural Mountains were where the supreme god Numi-Torum had cast his buttoned belt. As for the rivers, they were made by the vitkul vitkas, a mythical mammoth able to dig through the ground with its horns. Two vitkuls channeled the Sosva: vitkul ekva went along Lyapin, and vitkul oika went up to the head of the Sosva, where it dug two lakes including Yalpyng-tur.

From of old, the lake belonged to the Mansi line of the Sampiltalovs. As a rule, fishing was only allowed “for the caldron,” that is as food for the day; large-scale fishing could only be done in the years of famine by the decision of the entire family.

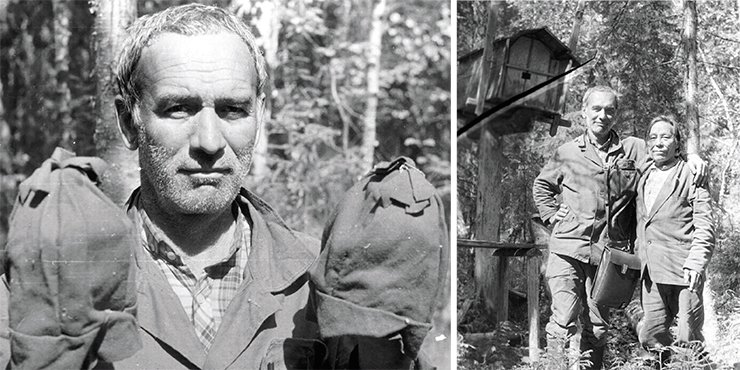

In 1990, N. I. Gemuyev and I had a chance to visit a unique Ural sanctuary – the cult place of Ner-oyka and Chokhryn-oyka. Lake Turvat is about a kilometer wide but spreads such a long way that its right bank gets lost behind a narrow strip of the forest. The other side boasts of a gorgeous view of the Ural Mountains, where reindeer breeders used to take their herds for the summer.

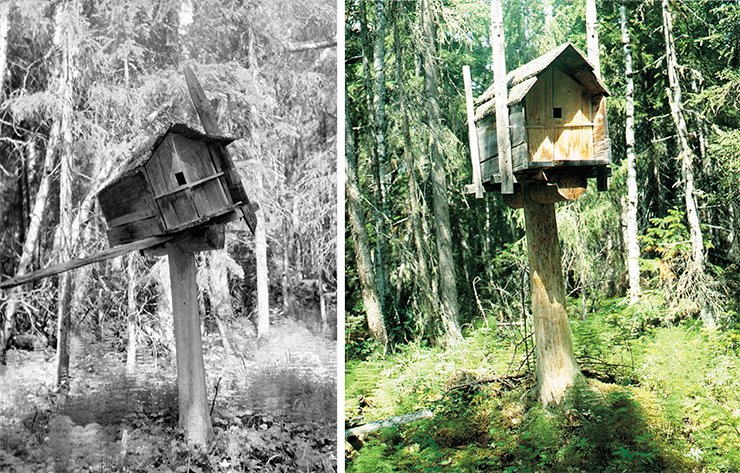

The bank that welcomed us turned out to be boggy, we first had to jump from tussock to tussock; then the lane became drier and the wood thinner so in some time we caught sight of the first small barn propped up on a single support: a little crooked house at the point of falling down. There were three small barns (sumiakh’s), a dozen meters apart from each other, and the difference in age was well noticeable. The first two turned out to be empty. We stopped and made fire at the third one.

The sumiakh was erected on a cedar stump and was made of chopped planks; nailed to the four corners of the structure were vertical columns, and the front two were topped with the masks of evil spirits, menkv’s. The front wall of the barn with a little square window in the middle was at the same time a door, held by a transverse cleanly carved out stick passing through the holes in the sidewalls. Next to the barn was a log with grooves which served as a ladder.

The sumiakh was erected on a cedar stump and was made of chopped planks; nailed to the four corners of the structure were vertical columns, and the front two were topped with the masks of evil spirits, menkv’s. The front wall of the barn with a little square window in the middle was at the same time a door, held by a transverse cleanly carved out stick passing through the holes in the sidewalls. Next to the barn was a log with grooves which served as a ladder.

To the left of the barn was a table on four supports, and five meters away we saw a bonfire site.

When we arrived at the location, our guide V. P. Sambindalov made a fire, put a fir branch in it, and when it caught fire, passed it over the sumiakh in circular motions in order to “clean” it. After that, he leaned the grooved log against the barn doorstep, went up along it and, having removed the transverse perch, opened the door.

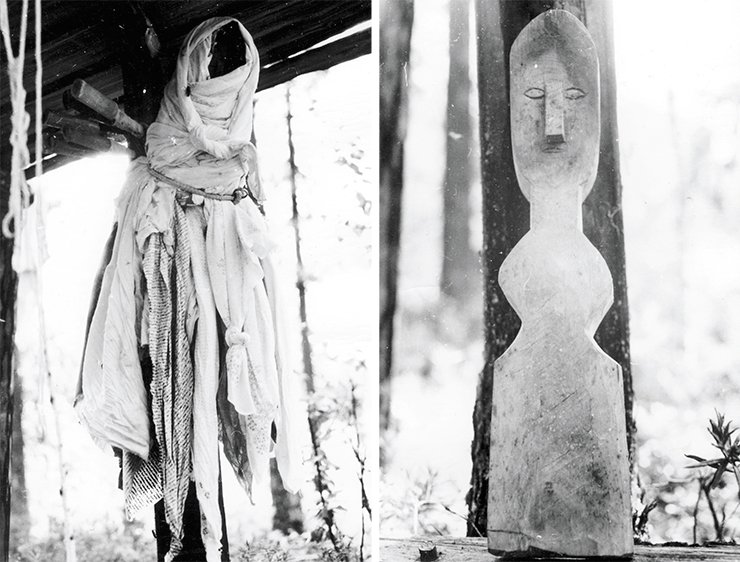

Inside the house, next to the back wall, there “sat” two figures, both in red-black peaked hats with tassels; their bodies were made of several dressing gowns wrapped in numerous light-colored kerchiefs. The kerchief tied over the hat accentuated the “face” of the patron spirit. The left figure – Ner-oyka – had a round face while the right one – Chokhryn-oyka – had an oval elongated face. The figures were about 60 cm high, and the diameter of the heads was about 20 cm.

Apart from the figures, there were gifts: bundles of kerchiefs, hats, and in front of Chokhryn-oyka, a few knives with wooden handles; right behind the door were shot glasses.

The guide poured vodka and put it in front of the patron spirits and the fire. Then, having doused a fir branch in vodka, three times waved it in the direction of the open entrance to the sumiakh (there were three shot glasses). They kept the spirits so as not to fall ill. If you happen to fall ill, you should come here, offer a treatment, and the pain will go. Chokhryn-oyka is the chief surgeon (V. P. Sambindalov).

Ner-oyka and Chokhryn-oyka are taken out every seven years, when a sumiakh is changed. It usually happens in spring, and a new barn is put not far from the previous one.

The wooden figurines placed on each side of the barn were called aras-ovyl-menkv-oyka (literally, “edges of the menkv-old man fireplace”) – these are the guardians; when the patron spirits went on business, the spirits-guardians were left to keep an eye on the dwelling. Each person who came to this sanctuary for the first time had to carve a menkv on wood.

After a traditional joint meal – purlakhtyn, during which the spirits were the first to be served, I. N. Gemuev went on enquiring the sacred place keeper about the details of the visiting ritual while I was taking pictures of the barns, taking their measurements and drawing the plan of the ritual site. Finally, the door was placed back, the ladder was put down, and we set off on our trip back home.

***

In the 19th c., each of the characters mentioned above must have had a sanctuary of its own, though they were all located in the same area. A. Kannisto wrote that in the north of the upstream Sosva there was a big lake called Yalpyng-tur near the mountain of Yalpyn-ner (“Sacred Ural”), where the patron spirit Ner-oyka (“Ural Old Man”) lived. It was prohibited to climb the mountain, and people who tried to do it died. Fishing in the lake was allowed only to men, but the fish caught could be eaten by women as well (ibid. p. 151).

In the second half of the 19th c., there was another sanctuary on Lake Yalpyng-tur. It was dedicated to Chokhryn-oyka, which was considered the patron of hunting and trapping. Nobody could climb Yalbyn-ner Mountain under penalty of death, but when the deity was in a good mood, it drove wild animals down, providing hunters with easy game. If hunting was not good, the Voguls would come to the sanctuary’s keeper and offer bloody sacrifices to Chokhryn-oyka. Travelers going past the mountain would surely stop and bow to the local deity. They would throw a piece of meat, pour a few drops of vodka and put a coin wrapped in silver foil under the tree trunk. A poverty-stricken person could tear a flock off his deerskin parka and fix it on the pine-tree trunk. Every three, seven and twelve years Chokhryn-oyka was offered public sacrifice. The Voguls, Ostyaks and even Samoyeds from all over the region would get together and offer up dozens of deer. The sanctuary’s keeper was at the same time the treasurer of his deity, often lending money or valuable pelts kept in the sacred barn to the needy tribesmen (Nosilov, 1904, p. 79–82).

K. D. Nosilov described a typical situation that took place when the Vogul Semen Salbantalov (misspelled for “Sambindalov”) was paying tribute:

“Having produced a package wrapped in birch bark, he passed it to the scribe…Old silver coins fell out of it.

– Where did you take so much silver? – the head shouted at him.

– From the shaitan, – whispered the Vogul, – from Chokhryn-oyka...

It appeared that, having no money, the Vogul went to the shaitan Chokhryn-oyka and under the shaman’s surveillance undid a few kerchiefs in which the worshippers put silver, and took it to pay tribute” (ibid. p. 196).

During one of his trips to the North, K. D. Nosilov managed to take part in a sacrificial offering conducted at a Chokhryn-oyka sanctuary. On a winter morning, several Voguls, led by the site keeper and the old man Sopra, who the researcher believed was a shaman, loaded onto sledges (there were at least ten of them) cast iron and copper caldrons, a huge fork made of iron and wood, trivets and supports of a similar size, and set off past Lake Yablyn-tur to Mountain Yelbyn-ner. Running after the sledges were deer meant to be sacrificed.

In two or three versts, the caravan arrived at its destination, and the animals were tied to the sledges. Walking ahead was the old man Sopra, who, from time to time, would take down long thin blue threads from the huge, combat ready bows with sharp arrows. These bows were all over the perimeter of a cedar wood so that you could only get in there following the path known to the keeper alone.

In the center of a wood clearing was a small barn on two supports, with antlers mounted on its roof. The Voguls knelt three times, praying to the deity. The old man Sopra climbed up the log with nocks for steps to the barn door and opened it. The Voguls knelt again in prayer, then got up and looked at the deity’s figure in silence.

Inside the barn was the materialized Chokhryn-oyka in furs, scarves and girdles; on its head were three topped hats of black, red and blue cloth decorated with copper jingles. The face was wooden, with a crude knot for the nose and lead bullets for the eyes. Around the idol were about a dozen painted and gilded wooden cups – in some of them were swirls and in the others, spice cakes and white bread. In the corners, there were dozens of broken knives; hanging on the barn walls were pelts of beavers, dark-brown foxes, sables, squirrels and gluttons.

Inside the barn was the materialized Chokhryn-oyka in furs, scarves and girdles; on its head were three topped hats of black, red and blue cloth decorated with copper jingles. The face was wooden, with a crude knot for the nose and lead bullets for the eyes. Around the idol were about a dozen painted and gilded wooden cups – in some of them were swirls and in the others, spice cakes and white bread. In the corners, there were dozens of broken knives; hanging on the barn walls were pelts of beavers, dark-brown foxes, sables, squirrels and gluttons.

The figurine of the guardian spirit was a wooden pole with a face carved on its end, ears and arms made of sticks, and no legs. The idol’s neck was wrapped in scores of silk kerchiefs, with Catherine and later times’ silver coins tied up in their ends. The sable gown was also smothered in kerchiefs, scrapes of brocade and cloths of all colors. Silver snowed in – silver coins of various denominations and ancient chiseled cups; the bottom of one cup had depictions of dragons and some monstrous birds and beasts, which reminded K. D. Nosilov of Egyptian and Persian art. The old man Sopra gave the researcher a 20-kopeck coin with Catherine II depicted on it and assured him that from then on every animal and bird would come his way.

The sacrifice was offered not far from the barn. Mounted above the fires were caldrons filled with melting snow. When the deer were put in front of the fires and two people clutched each looped rope, the old man Sopra suddenly started singing in a loud voice. The Voguls became vociferous; some of them strangled the deer with ropes; others shot arrows at them. The deer were butchered; the meat was placed in the caldrons, and the hearts, kidneys, ears, brains and livers were put in bowls. The treatment was doused with blood and carried to Chokhryn-oyka, with Sopra at the head of the procession. At the sight of the idol, the Voguls knelt with a cry and then howled wildly and frantically. The old man was the first to climb up the ladder to the barn and put the bowl in front of the figurine; all the others followed, after which they fell into the snow again continuing their loud prayers. After that, the pelts of the killed deer were hung on a perch next to the barn, and again the old man chanted incantations, throwing up his arms, with the Voguls chiming the prayers after him or falling into the snow and lying silently. Returning back to the sacrifice site, the Voguls had dinner made of the cooked meat (ibid. p. 86–95).

Chokhryn-oyka sanctuary in Ust-Tapsui

The village of Ust-Tapsui is situated on the right bank of the Severnaya Sosva, in the place where its right tributary, the Tapsui River, runs into it. In the late 19th c., it was a large Mansi community of 15 households counting 40 men and 39 women. The sanctuary is a kilometer away from the village.

In the mid-1920s, the aspiring researcher V. N. Chernetsov arrived here and described what he saw in one of his first papers (1927, p. 21–25):

“I will write about how the Vogul Khury-Kostia offered sacrifice to Chokhryn-oyka before going hunting in the forest. Early in the morning, Khury-Kostia, or Khury-khum, accompanied by the residents of the village, set out on a journey to the deity’s lodgings. At the head of the procession was a man in a small boat with home idols placed in a black box set on a deer hide. After him went Khury-khum with his son – they were carrying a white deer calf intended for the offering and a small bundle with home idols. Following them in their boats were all the Voguls of the village, who carried caldrons, bowls and all the rest of it.

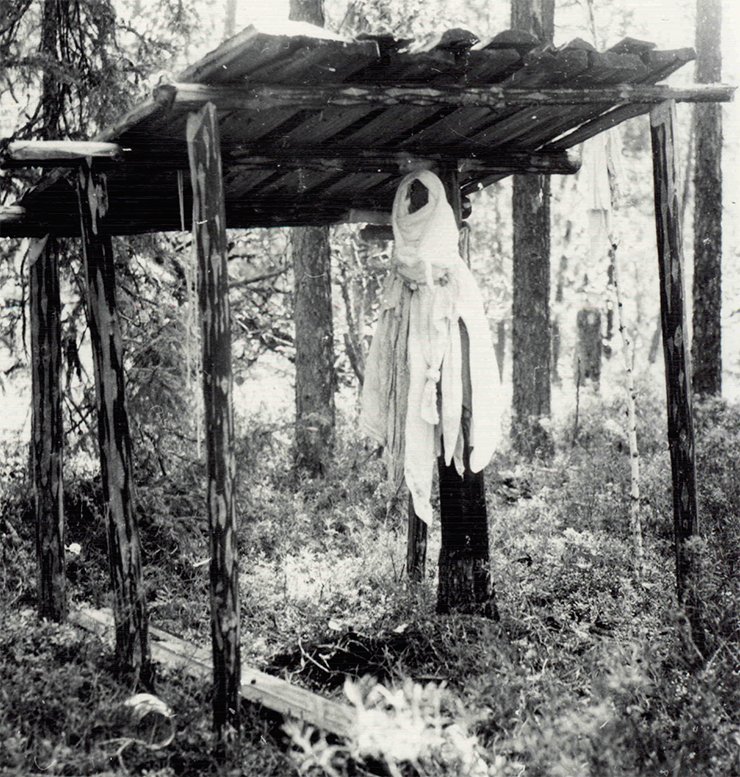

There was a butterfly type shed over Chokhryn-oyka and a scaffold next to it, where the gifts to the deity were kept in birch bark baskets. The rear column of the scaffold was stabbed with sharp knives, which had been sacrificed at different times. The scaffold was made at an old birch tree with plenty of deer antlers and a grey cow pelt in its branches. On the right was a big fireplace.

Chokhryn-oyka itself (the spirit-master of a narrow knife, a tutelary in hunting and fishing) has the form of a two-arshin log with a sharpened upper end. The deity’s nose, mouth and eyes were crudely carved; on its head was a cap made of seven strips of colored cloth and beaten up with sable. Its body was wrapped in a thousand kerchiefs and variegated cloths. In the ends of the kerchiefs and cloths money was tied up…

Once a year, the deity changes its clothes; no more than three of the oldest and most respected people are allowed to participate in this ceremony. During the changing of clothes, they put a birch bark screen round the deity so that no stranger can see the figurine. Young people are prohibited from looking at it...

Upon the arrival at the site, a fire was made. At the same time, Khury-khum put some butter, cracknels and bread into a wooden bowl and placed it in front of Chokhryn-oyka. After the bowl had stayed there for some time, it was removed, and its content was eaten. On the site, a log was put in front of the scaffold. A Vogul sat on it and began practicing sorcery on an old sabre. The sabre was hanging under the shed; they tied a towel to its ends, and the old man took the middle of it with his left hand. He was sitting planting his left elbow on his knee. Sometime later, his hand started jerking convulsively, and the jerking spread to the rest of his body. Consequently, the sabre was swaying too.

Having practiced sorcery for about ten minutes, the Vogul announced Chokhryn-oyka’s reply, favorable for Khury-khum, that there would be plentiful killing. The sorcery completed, the calf was brought to the site, its head turned towards the idol, and Khury-khum covered its head with a kerchief with coins tied up in its ends. Another Vogul came to the calf’s right side and knocked it senseless with a blow of a butt between the horns, after which Kostya stabbed a knife into the calf’s heart.

The calf was left for some time in front of the scaffold; then it was pulled aside and dressed out. Some parts – ribs, legs, liver, lungs and throat – were eaten raw whereas the rest of the carcass was put in the caldron that had been hung above the fire. When the meat cooked, it was put in a bowl and placed in front of Chokhryn-oyka, where it remained for about ten minutes. During this time, everybody present was standing silently in front of the scaffold, their heads down, with women behind all the others, their faces veiled with kerchiefs.

After that, they turned to eating and, having stood in front of the scaffold once again, began preparations for the journey back, which was performed in the same order as the journey there.”

***

Today, there is a house in Ust-Tapsui where a representative of the once big family of the Anemgurovs still lives. We managed to make it to the sanctuary three times: in 1989, 2007 and 2014.

It is situated on a clearing bordered with a thick fir grove. In 1989, the figurine of Chokhryn-oyka carved out of one piece of wood about 60 cm long and wrapped in white kerchiefs with coins tied up in the ends was fixed to a tall thin stump under a tent. Six knives were forced into the stump, and another seven knives were forced into the trunk of a nearby fir tree. The blades of the knives were wrapped in white cloths with coins at their ends. It is for a reason that the deity’s dwelling is a tent because one of Chokhryn-oyka incarnations is a dragonfly, which lives in the open air.

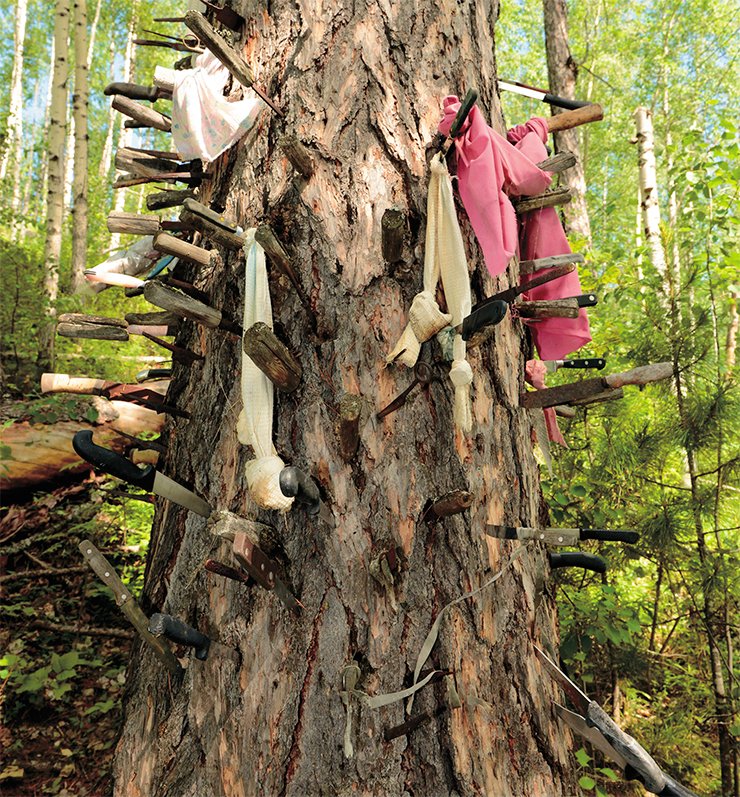

About a hundred meters from the tent were the remains of the old Chokhryn-oyka, which was described by V. N. Chernetsov. By the time of our visit, the scaffold had long fallen down. The pine tree growing next to it had 50 knives forced into it, and a lot of knives were on the support, where the figurine of the parton spirit used to be. On the planks of the scaffold were two birch bark baskets filled with rotten sacrificial kerchiefs. Inside one of the baskets were two anthropomorphic figurines with metal saucers made in the 1830s and depicting St. George for the faces. Also, there was another saucer of the same time with a deer depicted on it.

According to our guide I. V. Anemgurov, they would approach Chokhryn-oyka in case of an illness and would bring it a knife without fail. Besides, the patron spirit was paid a visit before a new moon, and a deer or a horse were sacrificed twice a year.

In 2007—2014, the sanctuary was functional in the same location, though in the center of the site a new clapboard tent with a backward batter was mounted on four pinewood columns. In the middle of the area under the tent, another column was dug in to which a figurine of Chokhryn-oyka, wrapped in white kerchiefs with coins tied up in the ends, was attached with ropes.

In front of the present tent, there lies the tent that had fallen, with a fireplace three meters away. Thrust into the trunks of the trees growing nearby are knives – offerings to the deity – with mostly wooden handles and narrow, iron blades. Also forced into the trees are a penknife, half of scissors and knives with plastic and wooden factory-made handles. The knives’ blades are wrapped in white cloths with tied-up coins.

The sanctuary looks somewhat neglected, which shows, for example, in the rotten pieces of the cloths making the deity’s outfit.

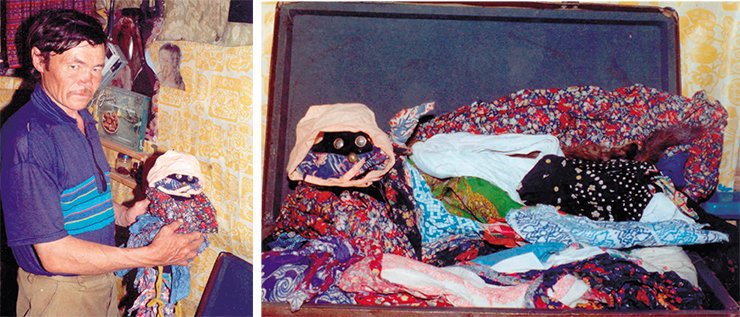

Interestingly, the Mansi Dunaevs, who live in the village of Timka-paul of the Tapsui basin, keep a figurine of the family patron spirit – Chokhryn-oyka`s son. It is made of kerchiefs of different colors; the outfit is girded with a yellow woolen string; there is a pink hat on the head; the eyes and mouth are metal buttons, with the hammer and sickle, sewed onto the black fabric. A sacrifice offered to this patron spirit was a deer, which was killed right here, in the room: “We put a deer pelt on the bed and a suitcase on top of it. Then we draw the kerchiefs out of the suitcase, put them on the deer’s back and pray. We make seven bows to the deity, turn one time cum sole, all in silence, you cannot make noise, with women standing a little apart, not coming close. Then we take the kerchiefs off and slay the deer. The animal’s blood should not spill on the floor: when the skin is cut, the host scoops out the blood with a mug, pours it into a bowl, puts a piece of meat into another bowls, and offers this together with a glass of vodka to Chokhryn-oyka-pyg. Even if a child falls ill, you have to ask gods to have mercy – I promise to slaughter a deer for the child to recover, put a kerchief into the box. Then you carve a deer out of birch bark, as though offering a sacrifice. After a real deer is sacrificed, we burn the birch bark deer” (A. T. Dunaev).

Chokhryn-oyka’s sacred site on the Great Ob

Another sanctuary of Chokhryn-oyka is situated two kilometers away from the village of Vezhakary, higher up the River Ob, on its right bank, on the slope of Chokhryn-oyka Mountain. In 1965, Z. P. Sokolova, a well-known ethnographer from Moscow, came here. There was a table under a tall larch, where they put a sacrificial meal for the deity. There was no figurine of Chokhryn-oyka – it was believed that he lived there but was invisible to people:

“On a high wooded peak there is a tall old larch with about 150 knives forced into it (sometimes, instead of a knife they offered a needle, a lancet or scissors). Attached to each knife is a cloth with tobacco (a traditional offering – Chokhryn-oyka is keen on smoking). Chokhryn-oyka “helps” to cure diseases. They offer knives and tobacco to it; in the winter, they thrust a knife into a wall of the house, and in the spring or summer, into the larch. This is the second larch tree; the first one, thrust with knives, dried up.

Khanty and Mansi used to come over here from all around. Those who could not come here to make an offering left it in Vezhakary. Our informant had several knives left by other people, and he brought them to Chokhryn-oyka. Women did not use to approach the larch tree; they would make a fire by the river. Men would make a fire near the tree. There is a wooden table close to the larch, and they put on it treatment and the knives brought. The sacrifice offeror pours some wine in a cup for Chokhryn-oyka; it remains on the table for some time, and then he drinks it. As he is drinking the wine, he appeals to Chokhryn-oyka asking for the recovery. Then he forces his knife into the tree. You cannot break trees or pluck grass on Chokhryn-oyka Mountain” (Sokolova, 1971, p. 220–221).

We visited the sanctuary in 2009, 2010, 2014, and 2015. On the mountain slope, there is a tall larch tree with knives –offerings to the deity – forced into it. Most of the knives (as well as of lancets and scissors) are thrust into the tree trunk at a height of about 1.0–1.5 meters from the ground while several knives are thrust much higher: they used to believe that a knife should be thrust above the others. “They used to stand on each other’s shoulders to force a knife as high as possible. And these knives – I can even remember who brought them. Babushkas would send them here for somebody who was not feeling well. A smith, he kind of forges health. They come here to be healthy.

They come to the larch tree quite often: both the few citizens of Vezhakary and numerous travelers along the river. How often do we come here? Maybe, three, four or five times a year. And not just us, other people come here, too. They may come on their own. We were here on June 7, and someone came here after us but they did not go through the village. Last fall we came here too, in September. So I came here twice last year. It is a rule with us: if somebody is not well, if he is ill or if the children are ill. And he is like a smith, a smith is healthy. My grandfather used to bring wild tobacco here” (V. Filippov).

When they visit the sacred place, they put a meal by the larch and thrust a knife into the tree trunk, the handle of which is wrapped with sacrificial cloth.

To sum up, we have quite detailed information about the three of Chokhryn-oyka’s sanctuaries located on Lake Turvat, in Ust-Tapsui and in the village of Vezhakary. In the two former cases, the evidence belongs to two chronologically different periods (late 19th century and 1990; 1926 and 1989–2014). According to the information supplied by V. N. Chernetsov, the patron spirits of Lake Turvat and Ust-Tapsui sanctuaries were brothers; the functions they had in common were patronage in hunting, deer breeding, fishing, and treating diseases as well as a distinctive token of offerings – a knife with a blade wrapped in a cloth. Virtually indispensable elements of the ritual space were a table, perches for sacrificial pelts, a fireplace and trees with knives forced into their trunks. Another matter that stands to mention is the wide popularity of these sanctuaries in the entire basin of the Severnaya Sosva, which has led to the custom of handing over gifts to Chokhryn-oyka through the keepers of the cult places dedicated to the deity.

Nonetheless, each sanctuary had its specific features. The figurine of the main character was made in different ways (and at different times): as a rule, it was an anthropomorphic wooden statue (Turvat, late 19th c., Ust-Tapsui, 1989—2014), and less often, it was made of fabric (Turvat, 1990). Sometimes, there was no physical image at all (the village of Vezhakary). The Ural Chokhryn-oyka has a more strongly pronounced function of a deer-breeding patron.

Chokhryn-oyka has two types of lodging: a plank barn and a tent (reasons for the latter have been discussed above). Some characteristics allow us to categorize Chokhryn-oyka as a forest spirit: decorating of the side columns of the Tuvat barn with the masks of the Menkv’s, the similarity of the Chokhryn-oyka figurine in Ust-Tapsui (1926) to a wooden Menkv statue; a larch (Menkv’s tree) taking the central stage at the Vezhakary sanctuary; and legends of Chokhryn-oyka executing justice together with other forest spirits.

Summing up, we should note that Chokhryn-oyka is one of the most popular characters in the pantheon of Mansi gods and patron spirits, which shows in the mass production of its (or its son’s) figurines and in keeping them at the village and home sanctuaries. Its popularity is attributed to the protection it offers to the Mansi’s most important trades: hunting, deer breeding and fishing, as well as to its well-known healing talents.

References

Baulo A. V. Sacred places and attributes of the Northern Mansi in the early 21 st century: an Ethnography Album. Khanty-Mansiysk. Yekaterinburg. Basko. 2013. P. 208, illustrated.

Gemuev I. N., Baulo A. V. Mansi sanctuaries of the upper reaches of the Severnaya Sosva. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAEt SO RAN. 1999. P. 240.

Nosilov K. D. With the Voguls. St Petersburg: Izd. A. V. Suvorina. 1904. P. 255.

Sokolova Z. P. Vestiges of religious beliefs of the Ob Ugrians // SMAE. 1971. V. 27. P. 211—238.

Chernetsov V. N. Voguls’ sacrificial offerings // Etnoghaf-issledovatel. Leningrad, 1927. N. 1. P. 21—25.

Kannisto A., Liimola M. Materialien zur Mythologie der Wogulen // MSFOu. Helsinki. 1958. V. 113. S. 444.

The photographs are the courtesy of the author