Mysterious Artefacts from archaeological sites and ethnographic complexes of the north of West Siberia

Archaeology and ethnography are for romantics, who get an opportunity to explore something unusual, unique and hitherto unknown.

Such finds are often only fragments of long-lost artefacts and are full of riddles and mysterious meanings hidden from an archaeologist or an ethnographer, who are able to solve them relying on their knowledge, experience and intuition, and sometimes restraining their wild imagination

Several years ago, a massive plate forged of white bronze was found in the north of West Siberia. It is a classical example of the famous Permian animal style, which was flourishing in the second half of the first millennium AD. It represents two male figures sitting on the back of a mysterious beast; they dropped their paddles while looking at the fish in the water below. The men’s hands are like bodies of wriggling animals; their palms are like birds’ open beaks. Unfortunately, the plate was broken, and its left part had been lost long ago. The round silver badge found at one of the medieval shrines of the Lower Ob River helped to reconstruct the missing fragment. The badge shows a similar couple of men sitting peacefully on the back of a large animal whose tail, covered with a rhombic grid, makes it easy to identify the animal as a beaver.

Another item of interest was found in the Yamalo–Nenets Autonomous Okrug: it is a half of a large bronze plate. It is likely to have been an image of a bear in profile walking to the right, which resembles a similarly shaped article found on the unknown medieval site in the Tomsk oblast. The Yamal fragment has three paws of a bear, with pictures of two birds and a beaver on them. Thus, the missing paw is sure to have had a picture of an animal on it as well. There are five anthropomorphic figures in the upper part of the plate; the overall size of the article allows us to assume that initially there had to be seven figures.

Faceless

In 2013, the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography in Novosibirsk received a large round badge split into several slices. It was found in the upper reaches of the Konda River, not far from the confluence with the Ess River (Soviet district, Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug—Ugra). The cultural layer of the unknown site, presumably a small necropolis of the 10th–13th centuries that included several burial mounds, had been destroyed by heavy tractors in the course of logging.

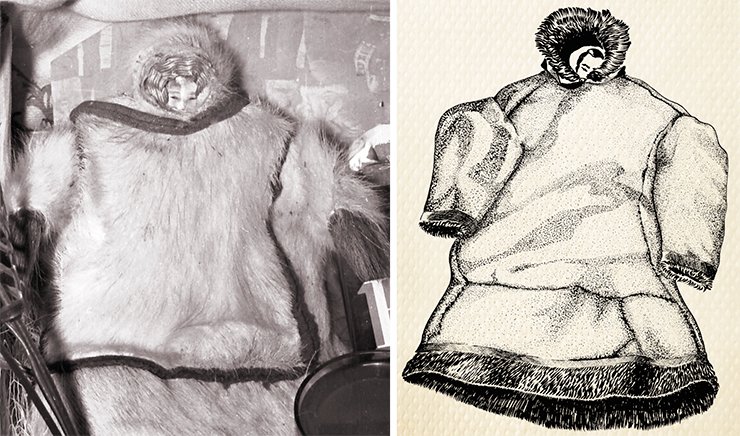

One of the burial mounds contained the remains of a dead person wearing a fur coat of rough black fluff (possibly bear skin). The slices of the silver badge were lying face down in a certain order on the chest part over the fur coat.

Long ago, this article was forged from silver bullion and cut round with metal scissors. The picture on the face side of the badge was made by gilding, embossing, and engraving. Then the article was sold (or delivered) from the workshop to the owner.

Later the badge was improved by the owner himself or by the craftsmen: the edge of the item was ornamented by incusing a row of large-sized “pearls”; then a hole was made to which a brass ring was attached, which made it possible to wear the badge as a pendant.

After the death of the owner the badge was split into slices and put into the grave. In fact, it was destroyed so that it could pass to the other world together with its owner.

The fragment of the badge depicting the man’s face was never found.

The diameter of the badge is 17.5 cm; the diameter of the central medallion is 10.5 cm. It shows a man sitting in an oriental position; he is pulling a bending woman by her long braid and touching her head with his right palm. The background is gilded.

The man is wearing a robe with sleeves rolled up and high boots with a side seam. The robe is ornamented with circles grouped in three: it is a leopard skin motif well known in Middle Asian toreutics of the 9th–10th centuries.

The woman’s figure is depicted more thoroughly: she is wearing a long dress with short sleeves (possibly a mantle, a tunic, or a shirt). Her clothes are ornamented with wavy and parallel lines, which could signify folds or a tabby fabric; the edge of the clothes is decorated with festoons. On her head, she is wearing a fitted polka-dot scarf or cap, revealing some hair. The ankles and the right wrist are adorned with bracelets made of large circles. On her feet, there are thick-soled sandals with a narrow strap and a large button.

The woman has a round face, big almond-shaped eyes with large pupils, long thin connected eyebrows, a straight nose, and small lips. She has a long heavy braid tied with ribbons.

The plot depicted on the badge is hard to interpret mainly because of the missing fragment with the man’s head (face). The simplest interpretation is that it is a scene of violence.

The dating of such finds allows us to presume that the badge was made in the 9th–10th centuries. The place of production is also difficult to identify; it may have been Eastern Europe. The Kondian badge, judging by such details as the man’s oriental position and the woman’s sandals, has a pronounced southern, Central Asian specificity. This is the first time such a plot and a woman’s unusual (round) face have been found in this region.

The fragment of the badge with the man’s face was never found. I am convinced that it had not been buried there at all.

The badge was destroyed by cutting it into five longitudinal slices, and then the right one was split into three parts by blows across its width. Moreover, it was not just cut into three pieces, but the central fragment with the man’s face was cut out from the badge. What for was it done?

It could be assumed that, in his lifetime, the badge owner identified himself with the male character depicted on the badge, and so, apparently, did his tribe. After the man’s death, his “portrait,” the face, was removed from the funerary accessories, most likely with a specific purpose of making his postmortem image, a vessel for his soul. In the late ritual practice of the Ob Ugrians, the creating of a figurine of the deceased, a temporary receptacle for one of his souls (itterma), has been known at least since the beginning of the 18th century.

A tradition of making similar figurines may have existed back in the Middle Ages; for example, anthropomorphic dolls with faces dating back to the 8th–9th centuries were found near Surgut. Their bodies were made of twigs; the faces, made of bronze or wood, were sewn onto the dolls, some figurines had strands of hair that may have signified a connection with a particular person. It is possible that such a doll was made for the Kondian man, but his face was to be the fragment specially cut out of the silver badge.

Figurines of the deceased (itterma, ittarma) were widespread among the northern groups of the Khanty and Mansi in the 18th–20th centuries. The Lyapin Mansi also had a tradition of attaching (sewing on) the dead person’s photograph to an itterma doll. Such close semantic similarity (the fragment of the badge and the face—the photograph and the face) combined with the version that the fragment of the badge might have been attached onto a figurine as a postmortem vessel for a soul allows us to make a tentative suggestion that the burial complex found in the upper reaches of the Konda River was Ugric.

Family joys

Another group of riddles is connected with trying to explain complicated visual plots.

In 2015, a very interesting badge was found in the course of undocumented excavations in the east of the Sverdlovsk oblast. It is made of copper (tin-plate) with traces of tinning. Its diameter is 15.3 cm, and it may date from the 12th–13th centuries.

The face side of the badge depicts two embossed anthropomorphic figures; above them are two birds. Since the plot is unique and has no analogs, we may suggest only a hypothesis.

To the left, there is a woman; the man is to the right. The woman can be identified by her hairstyle and explicit breasts with nipples. She is pregnant, since she has swollen breasts, a large belly (its roundness is underlined by the belt turned down); her hand is over the belly as if defending the fetus. The position of the characters’ arms, stretching towards each other, symbolizes an embrace.

The birds might be of different sexes too (the left one has a longer tail and a crest on the head) and could signify a blessing: medieval art is known to have depicted two doves facing each other, which meant peaceful intentions of the parties; the birds usually accompanied the allegoric figure of concord. A couple of cooing doves symbolized family happiness and sexual harmony, while a gentle dove was a metaphor for a loving and considerate wife. Thus, the scene could be understood as a manifestation of marriage and procreation.

Silver idol

In the 16th–17th centuries, the story of a “Golden Woman,” the legendary idol of the peoples living beyond the Urals, became widely known in Western European literature. The search for it had lasted for decades, but to no avail. When Russian researchers and adventurers abandoned the hope of finding the Golden Woman, they switched their enthusiasm to the quest for a “Silver Woman.” This time their efforts were not in vain. At the end of the 19th century, they recorded a story about the Silver Woman forged as a cast from the Golden Woman. It represented a woman sitting naked; it was kept in a box on the holy shelf in a Vogul yurt in the Urals. When going hunting, the owner wrapped the figurine in an old silk scarf, together with silver rubles, and carried it on his back in a small pouch made from the ear of a young elk. The “woman” was believed to help women and hunters. During the seven- day celebration in its honor, people from the entire neighborhood brought their gifts to the protective spirit: deer, silver, brocade, silk, sables and foxes; women made clothes and decorated it with precious things. The “woman” was offered blood and meat on silver dishes. The Voguls bowed before the deity and prayed to it.

Nearly one hundred years later, in 1962, the Khanty-Mansi Regional History Museum received a figurine of a female protective spirit from the upper reaches of the Kazym River (Beloyarsky district, Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Ugra). Eleven silver plates attached to its clothes allowed the researchers to identify it as one of the variations of the Silver Woman. Nearly at the same time P.E. Sheshkin, a descendant of the Mansi princes, spoke about a Silver Woman, a female figurine with an “Indian” face, which he had seen.

In 2000, the members of the Polar Ethnographic Group of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, SB RAS, heard a story from the northern Khanty about an ancient figurine that had been in one house since the good old times when “the Khanty conquered Rome.”

According to the family legend, the owner’s grandfather, while hunting in the taiga in the late 1930s, stumbled over a trunk lid hidden in the grass. The trunk contained several fetishes including a figurine and small silver figures of animals and birds as well as skins of small animals and scarves–gifts to protective spirits. Since the Ob River Ugrians consider any unusual thing found occasionally to be heaven-sent, the hunter took the items home, thus giving the sacred objects a new life.

In recent years, the figurine has been the family protective spirit; it is kept in the inner porch, in a cardboard box with pieces of cloth as gifts. The figurine itself is wrapped in several scarves and is wearing a miniature deer fur coat. When holidays come, it is offered a glass of vodka and a holiday meal, as are the other protective spirits; then the family members ask it for assistance and blessing. They call it evi, a girl.

Interestingly, this is the second hollow silver figurine discovered in the north of West Siberia. The first one was the figure of an elephant in the Mansi shrine of the “Old Eagle Owl,” in the upper reaches of the Northern Sosva River; it was there in the late 19th–early 20th centuries. The elephant acted as a secondary idol, the “threshold guardian” of a small barn. The legend about the elephant is much the same as the story of finding the female figurine: an Ostyak went hunting, traced an animal and came to the “mammoth” lying in the snow. It was found so long ago that, according to the Ostyak, “my father’s father cannot recall it.”

Oriental silver dishes (plates, chalices, salvers, jugs, etc.) are known to have been supplied to the North back in the 7th–8th centuries: Middle Asian merchants exchanged them for fur, walrus tusks and even hunting birds. Due to the utmost value and sacredness of the white metal, most silver articles went to the Siberian shrines to continue their life as ritual accessories. After the places of worship had disappeared or had been destroyed, silver went under the ground to reappear hundreds of years later as buried treasure. The unique medieval items are sometimes kept at home or in settlement worshiping places of the Khanty and Mansi.

Back to our statuette: the girl is holding the head of an antelope in her hands. The statuette is 25 cm long and 12 cm high. It is made of silver, partly gilded and hollow; the eyes are made of carnelian. In the upper part of the head there is a round hole nearly a centimeter wide. She has an unusual hairstyle: most of her head is shaved; only a narrow line around the forehead remains intact. There are several curls on the left and right of the back of the head. She has earrings made from two rings and a round pendent.

She is wearing a tight jacket with a full collar and short sleeves, and there is a belt wrapped around her waist. She is also wearing high boots with short wide tops.

The antelope’s head has short spiral horns (only the right horn has remained), an opening in the mouth and open ears pricked up. The antelope’ eyes are made of carnelian.

The girl seems to be flying. While the flying anthropomorphic figures depicted on Iranian and Central Asian silver plates have knees bent at different angles, the girl’s legs are kept together. According to Professor B. I. Marshak, the girl’s position reminds us of the position of an acrobat performing gymnastic exercises. The antelope’s head in the girl’s hands might be the answer. It is a rhyton, i.e., a vessel for wine. We see a gymnastic exercise with a wine vessel. The acrobat entertains the guests while serving them wine. The shaven head of the girl looks very much like the hairstyles of putty in the art of Eastern Turkestan. In this case, however, the head was shaved to ensure a tight fit for a cap so that a pole could be set on it for acrobats to perform various acrobatics.

Not only is the head of an antelope an image of rhyton, but the statuette itself appears to be an intricate silver rhyton. Wine was poured into the opening in the girl’s head. Then the statuette was put on the palm, moved aside and upwards, and tilted a little to let the liquid flow along the girl’s hands into the antelope’s head. Then the wine streamed through the tube, which had once been installed in the antelope’s head, into the mouth of a drinking person.

Rhytons, which were once popular in Greece and Rome, were reborn later in the early medieval cultures of Central Asia, especially in Iran. Rhytons made as hollow silver figurines have survived to our days as single copies. For example, there are vessels made in the form of a lying horse in the Cleveland Museum of Art; vessels in the form of a standing horse in the Louvre; and the “Bashkir” horseman in the collection of the Kremlin Armory.

The rhyton was apparently manufactured in one of Central Asian handicraft centers at the end of the 8th century or in the first half of the 9th century. Generally speaking, the decorative rhyton is, first of all, an item of art belonging to the secular and aristocratic culture although its whimsical shape could be associated with some religious symbols. In the course of trade relations, this article was brought to the north of West Siberia and was included into the ritual practice of the local peoples; it has been a valuable and rare image of a female protective spirit for over one thousand years.

To complete our short story about the mysteries of the articles found on the archeological sites and in ethnographic complexes in the northern areas of West Siberia, we should thank our fortune for the admirable finds and for the opportunity to study them, to think about them and to solve the mysteries they hide.

References

Baulo A. V. Without a face: a silver plaque from the eastern slopes of the Urals // Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia. 2013. N 4. P. 123–128.

Baulo A. V. and Marshak B. I. Silver rhyton from the Khantian sanctuary // Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia. 2001. N 3. P. 133–141.

Gemuev I. N. Mirovozzrenie mansi: Dom i Kosmos (Mansi’s Worldview: Home and Cosmos). Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1990 [in Russian].

Karacharov K. G. Antropomorfnye kukly s lichinami VIII—IX vv. iz okrestnostei Surguta // Materialy i issledovaniya po istorii Severo-Zapadnoi Sibiri (Materials and Studies on the History of Northwestern Siberia). Yekaterinburg: Ural. Gos. Univ., 2002. P. 26–52 [in Russian].

Nosilov K. D. U Vogulov (At Voguls. Essays and Sketches). St. Petersburg: Suvorin Publ., 1904 [in Russian].

Sokolova Z. P. Khanty i mansi: vzglyad iz XXI v. (Khaty and Masi: Looking from the 21st Century). Moscow: Nauka, 2009 [in Russian].

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project N 14-28-00045)