The Kolyma Shaitans: Legends and Reality

A unique “shaitan” burial was discovered on the bank of Omuk-Kuel Lake in the Middle-Kolyma ulus in Yakutia. According to the legends, buried in it are mummified remains of a shaman woman who died during a devastating smallpox epidemics in the 18th c. In an attempt to overcome the deadly disease, the shaman’s relatives used her remains as an emeget fetish. The author believes that these legends reflect the real events of those far-away years

A unique “shaitan” burial was discovered on the bank of Omuk-Kuel Lake in the Middle-Kolyma ulus in Yakutia. According to the legends, buried in it are mummified remains of a shaman woman who died during a devastating smallpox epidemics in the 18th c. In an attempt to overcome the deadly disease, the shaman’s relatives used her remains as an emeget fetish. The author believes that these legends reflect the real events of those far-away years

The Arabic word “shaitan” came to the Russian language from Turkic languages. According to Islamic tradition, a shaitan is a genie, an evil spirit, a demon. During Russian colonization and Christianization of Siberia, all sacred things used by the aborigines as fetishes, patron spirits of the family and the tribe, grew to be called “shaitans.” There are various facts, dating to the 18th and 19th cc., confirming that this word also referred to the mummified remains of outstanding shamans.

In the 1740s, a member of the Second Kamchatka Expedition Yakov Lindenau wrote, “Meat is scratched off the [shaman’s] bones and the bones are put together to form a skeleton, which is dressed in human’s clothes and worshipped as a deity. The Yukagirs place such dressed bones…in their yurts, their number can sometimes reach 10 or 15. If somebody commits even a minor sacrilege with respect to these bones, he stirs up rancor on the part of the Yukagirs… While traveling and hunting, the Yukagirs carry these bones in their sledges, and moreover, in their best sledges pulled by their best deer. When the Yukagirs are going to undertake something really important, they tell fortune using these skeletons: lift a skeleton up, and if it seems light, it means that their enterprise will have a favorable outcome. The Yukagirs call these skeletons stariks (old men), endow them with their best furs and sit them on beds covered with deer hides, in a circle, as though they are alive.” (Lindenau, 1983, p. 155)

Two hats for the idol

In the late 19th c., a famous explorer of aboriginal culture V. I. Jochelson noted the changes that occurred in the ritual in the last century and a half. So, the Yukagirs divided among themselves the shaman’s meat dried in the sun and then put it in separate tents. The dead bodies of killed dogs were left there as well.

“After that,” V. I. Jochelson writes, “they would divide the shaman’s bones, dry them and wrap in clothes. The skull was an object of worshipping. It was put on top of a trunk (body) cut out of wood. A caftan and two hats – a winter and a summer one – were sewn for the idol. The caftan was all embroidered. On the skull, a special mask was put, with holes for the eyes and the mouth… The figure was placed in the front corner of the home. Before a meal, a piece of food was thrown into the fire and the idol was held above it. This feeding of the idol… was committed before each meal.” (V. I. Jochelson, 2005, pp. 236—237)

The idol was kept by the children of the dead shaman. One of them was inducted into the shamanism mysteries while his father was still alive. The idol was carried in a wooden box. Sometimes, in line with the air burial ritual, the box was erected on poles or trees, and the idol was taken out only before hunting or a long journey so that the outcome of the enterprise planned could be predicted.

With time, the Yukagirs began using wooden idols as charms. V. I. Jochelson notes that by the late 19th c. the Yukagirs had developed a skeptical attitude towards idols and referred to them as “shaitans.” In this way, under the influence of Christianity, the worshipped ancestor’s spirit turned into its opposite – an evil spirit, a devil, a Satan.

Tungus saitaana

In the late 1930s, the Yakut ethnographer А. А. Savvin collected from the Evenks (the modern name for the Tungus) living in the Verkhoyansk region of Yakutia evidence about saitaana. This was the name given to the mummified corpses of strong shaman men and women, used as charms. In all probability, the Tungus “shaitans” emerged as an imitation of the Yukagir ones.

Sometimes, these would just be heads of figurines made of powdered wood. Then a “vivification” ritual was conducted: the idol was rubbed with pieces of dried man’s meat, washed in the sacrificial deer blood, dressed in shaman’s clothes, and handed in a small tambourine. It became the family’s charm. It was worshipped as Baianaia, the patron of hunting, and the Yukagirs were wary of giving the idol offence as it could punish them for it. The “shaitan” was kept in a leather sack, fed, and fumed with smoke or vapor coming from sacrificial food. For a long time, there was no evidence about what happened to saitaana later and whether it was buried until, in 1955, a resident of the remote Yakutian village Aleko-Kuel told the author that a few years ago he had seen, on the bank of the lake, a triangular log-house with a “shaitan” seated on a pole inside.

We managed to check this valuable information much later, in 2009.

On the bank of Omuk-Kuel

Residents of the Aleko-Kuel village told us that in the old times this locality was inhabited by the Omuks – this is what they called the Evenks. The big lake in ten kilometers from the village is called Omuk-Kuel, which means the “Evenk’s lake.”

On its woody bank, on a cushion made of moss, reindeer lichen and cloudberry, is the “shaitan’s” grave. It looks like a small rectangular log-house squeezed in between two old tree stumps, without whose support it would have fallen apart long ago. It is roofed with poles, and under it is a small burial chamber (45 cm x 45 cm) with human remains.

In one corner are pelvic bones, and in the other are the bones of lower limb. Between them is a skull, with the lower jaw missing and a hole in the occipital bone. The spinal bones and ribs are placed on the chamber floor in a relatively anatomical order between the pelvis and the skull. The upper limb and shoulder blades are missing. They must have been taken by the dead person’s relatives to be used as talismans or fortune-telling aids. The layout of the remains indicated that the person was buried in a sitting posture, with the legs drawn closely to the chest. Judging from the length of the limbs, he (or she) was at least 1.6 meter tall. The dead person’s face is presented to the south.

Apart from the human remains, the following offerings were discovered in the chamber: a match box, cigarettes, and tea wrapped in foil. Also found in the grave was a wooden stake with a rotten end. The second stake was outside, propped against the log-house. Both stakes were flat, with at least 2 to 3 cm point, which means it was impossible to stick them through the corpse. Another testimony in support of this statement is the intact coccyx.

A history teacher from the village of Ebeekh of the Second Khangalass nasleg V. I. Yefimov told us that in there used to be a “shaitan” in the locality of Duense, sitting tied to a long stake inside a fence. This evidence cannon be verified because, regrettably, the grave is no longer there.

A diver, beads and tokens

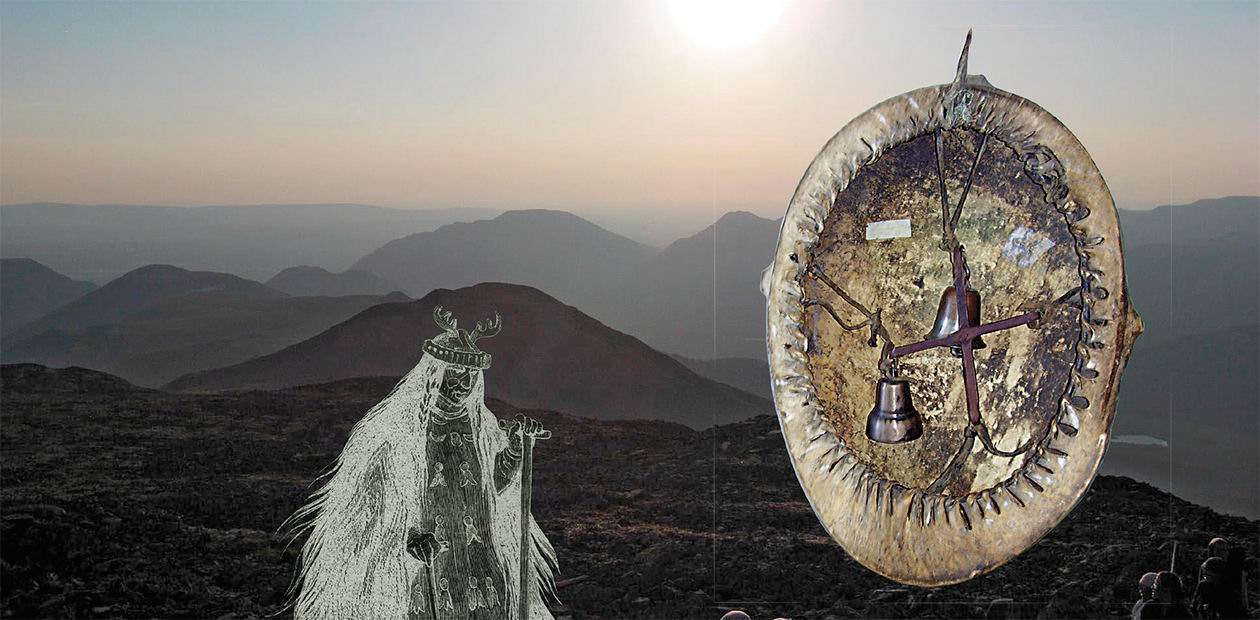

Under the turf covering the chamber floor, things that used to adorn the dead person’s clothes were discovered: an iron figurine of a diver, a bronze disc with an openwork solar chain, three brass tokens with holes and plenty of blue, white, and black beads. Undoubtedly, all these were attributes of the shaman’s costume: the diver was attached to the back or to the shoulders, the solar disc was hung on the chest, the token decorated the breast plate, and the beads were sewn on the clothes and footwear.

Depicted on one of the tokens is a crown and a shield with lilies; the inscription PFENNING can be clearly seen. Another token has the same shield and lilies, and the reverse side shows a man sideways, in a long wig and a jabot, and a circle-wise inscription in Latin letters. The Yakutsk local Lore Museum has 18th-century brass tokens discovered in a horse burial. Two of them are identical to those described above.

There could have been much more decorations. According to local residents, until the early 1980s the grave and remains buried in in had been intact. This statement is confirmed by the head of the Mammoth Museum with the Institute of Applied Ecology of the North P. A. Lazarev, who worked at Omuk-Kuel Lake at the time.

No ritual structures have been discovered in the vicinity of the grave. Sixty steps to the north of the burial is a rectangular foundation of the tordokh chum, a winter version of a dwelling. The proximity of the chum and the log-house suggests that they used to form a single ritual complex aligned from the north to the south.

The village old-timers told us that in about 500 meters from there, near Lake Omuk-Unguokhtakh, there was the grave of another Evenk shaman, but they declined from indicating its exact location.

Legends and facts

According to the director of the local Museum of Local Lore Dmitry Ilyich Vinokurov, in the old days a chum was mounted above the shaman, and on both sides of it, in triangular fences, were buried his two assistants.

When the Omuks were passing by, they would stop and feed the “shaitan,” putting a lit pipe in his mouth. They say that he whiffed in, and the smoke went from his mouth to the chum’s upper hole. Dmitry Ilyich used to be a deer herder and a hunter but he had never seen the “shaitan” there.

The village horse breeder V.S. Bubiakin told us that in the 1960s he saw a “shaitan” stuck on a stake. The stake went through the holes in the backbones and pierced the skull. The “shaitan” had no clothes, only some rags. He was facing the south.

Bubiakin himself was friends with the Evenk shaman N. Ya. Sleptsov, who was buried near Lake Diarkhataakh, in the Laiylla locality. When Bubiakin happens to be there, he feeds the fire, calling his friend by the name and patronymic. He believes that the shaman’s hypnosis lasts 300 years. He says he can still feel the shaman’s power. The former director of the Local Lore Museum Vladimir D. Batiushkin told us that in 1981 or 1982 an architect from Yakutsk, Seraphim Banderov, came to those parts. It was he who unearthed the “shaitan.” Batiushkin remembers the photographs Banderov showed him. There were bones inside a triangular log-house and no head. Vladimir Dmitrievich told us that the architect’s life after that visit was not happy. He believes that his early death was caused by the “shaitan’s” revenge.

The Administration of the First Khangalass nasleg showed us the book by the journalist V.Ye. Vinokurov, which contained an interesting legend.

A long time ago, an epidemic of smallpox killed almost all Omuks. The few survivors stacked the corpses of their relatives by the water and left, taking along with them the bodies of three women. They dried them up, turning them into the emeget fetishes. The Omuks were hoping that with the fetishes would help them to escape the deadly disease but, having seen that the idols were powerless against smallpox, left the mummies on the bank, making triangular fences for them.

Only one of the three graves has preserved. The Omuks moved to the Oluere tundra. At the threshold of the 19th and 20th centuries, shaman Niukulachaan Oilun came to those places three times to perform the ritual of blessing the spirits of his senior aunts (Vinokurov, 2008, p. 22).

A repercussion of the ancient legend must be the grave on the bank of Omuk-Kuel Lake. The “shaitan” buried in it is an Evenk shaman woman who died of smallpox. This could have been the black smallpox epidemic of 1782.

It is known that the arangas (grave platforms) can survive up to a hundred years, and in the northern conditions even longer. If the shaman woman’s relatives came there at the end of the 19th c., they could have readjusted the grave made in the previous century.

An indirect proof of referring the grave to the pre-Christian period of Yakutian history, i.e. late 18th or early 19th c., is the absence of a cross. The small size of the chamber and the unusual layout of the bones suggest that this is the burial of the remains of a previously mummified person. The solar disc and the “shaitan” orientation towards the south are indicative of a connection with the cult of the Sun, which implies that the deceased could not have been a “black” shaman.

References

Vasil’ev V. E. Sajtaan // Kul’turnoe nasledie narodov Sibiri i Severa: Materialy V Sibirskih chtenij. SPb.: MAJe RAN, 2004. Ch. 2. S. 194–197.

Vasil’ev V. E. Jukagirskie sajtany (voprosy genezisa shamanskih pogrebenij) // Sibirskij sbornik–1: Pogrebal’nyj obrjad narodov Sibiri i sopredel’nyh territorij. Kn. 2. Spb.: MAJe RAN, 2009. S. 191–198.

Vinokurov V. E. Velikoe pereselenie: predanija, mify, legendy, stat’i. Srednekolymsk, 2008. 153 s. (Na jakut. jaz.)

Iohel’son V. I. Jukagiry i jukagirizirovannye tungusy. Novosibirsk: Nauka, Sib. otd-nie, 2005. 675 s.

Lindenau Ja. I. Opisanie narodov Sibiri (pervaja polovina HVIII veka): Istoriko-jetnograficheskie materialy o narodah Sibiri i Severo-Vostoka. Magadan: Kn. izd-vo, 1983. 176 s.

Tokarev S. A. Rannie formy religii i ih razvitie. M.: Politizdat, 1990. 662 s.

This project has been performed in the framework of the RAS Presidium program “Historical-cultural heritage and spiritual values of Russia”, section “Sakha spiritual culture: traditions, current state and development prospects”