The Story of a Shaman Drum

Added to the ethnographic collection of the Museum of History and Culture of the Peoples of Siberia and Russian Far East at the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography SB RAS (Novosibirsk) is another exhibit - a drum of the Altai shaman Kondrat Tanashev.

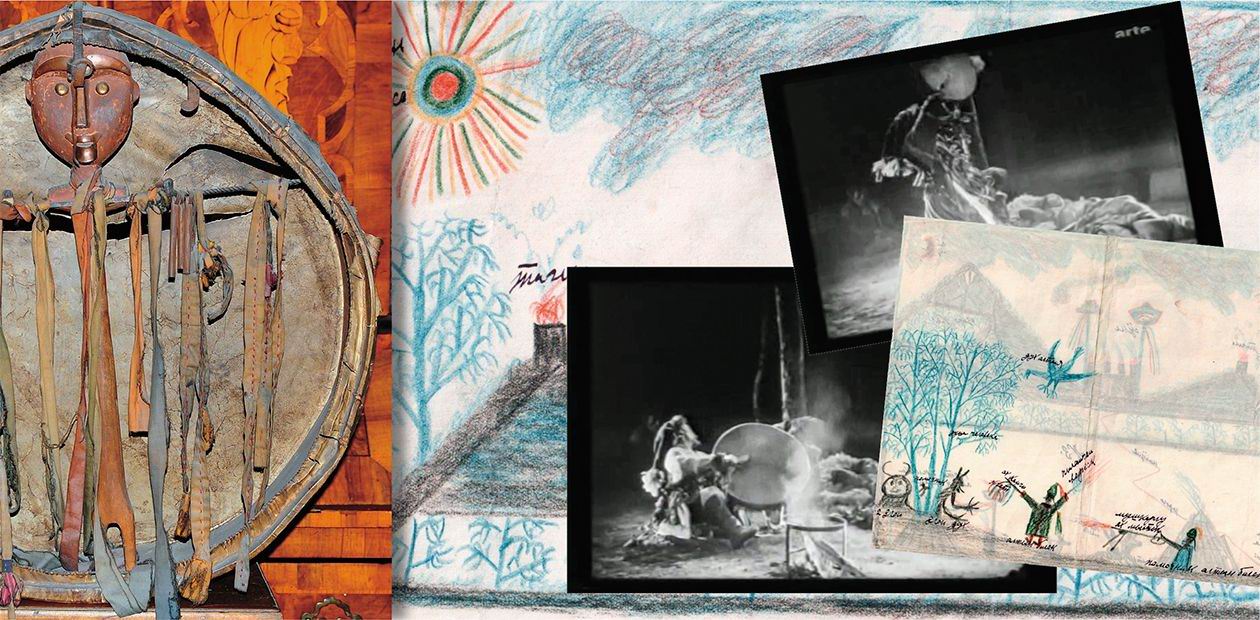

This musical and ritual instrument was kept at the home of the well-known film director Grigory M. Kozintsev. In 1930, he was making his film Alone in Gorny Altai, where he met Tanashev, an unusual person and adventurer, in a sense, but undoubtedly talented. The film director invited Kondrat to Leningrad and shot the episode in which the shaman was beating the drum. The very drum. This was the shaman's winged horse. Speeding it with its whip-tampon, the shaman traveled across the worlds: up to the sky and down to hell. Attached to the drum's handle is the wooden head of Ul'gen', Altaian supreme deity, who grants people the gift of becoming a shaman; on the exterior there is a drawing: the sun, stars, rainbow, and a vertical symbolizing the world tree or a horse line - the Universe in miniature.

Having stayed with Grigory Kozintsev as a souvenir of the filming, the drum held pride of place in his study. And now, eighty years later, it has come back from the banks of the Neva to Siberia.

The son of the film director, Doctor of History and Senior Researcher at the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) Alexander G. Kozintsev has donated the drum to the Novosibirsk Museum as he believes that this is its proper shelter

“The great breaking point,” this is what Stalin called the year 1929. A breaking point in the life of the nation and a breaking point in the hearts of the artists who wanted to keep up with the times and remain themselves at the same time. “It has never been as difficult to think about a new script as it is now,” wrote Grigory Kozintsev to his childhood friend Sergey Yutkevich in May 1929. “I should probably do my best to struggle with my harmful taste and take up things that seem alien at first sight.”

New time, new tasks

At that time, the founders of the FEKS (The Factory of the Eccentric Actor) group – my father and his companions in art, the film director Leonid Trauberg and the genius cameraman Andrei Moskvin – had not yet turned thirty; the artist Evgeny Enei, who worked with them, was a bit older. Behind were the brilliant 1920s, when art was in zenith. “FEKSes” had released seven silent films, some of which (The Overcoat, SVD, New Babylon) were acknowledged masterpieces all over the world; in the Soviet Union, however, they were criticized for pessimism – their characters were mavericks with tragic fates.

And then new time came and new tasks were set. The group, together with the actress Elena Kuzmina, goes to the Ust-Kan district in Gorny Altai to shoot the film Alone. Despite its title, the film was intended to show not only the loneliness a person suffers in the inhuman world but also solidarity of people in their fight against inhumanity. Music for the film, which was designed to be entirely talking but turned out to be half silent because of shortcomings in technology, was composed by Dmitry Shostakovich and lyrics for the songs by Nikolai Zabolotsky. The story of a girl who came to a remote village in the Altai to acquaint children with the new ideology and almost perished in her struggle with the old one was a great success in its tragic part. As for the optimistic finale, my father’s apprehensions came true. As he wrote later, “the last parts of the film were a failure. The theme of the state’s assistance was abstract and schematic.” Whatever the case, this film is still studied by experts in cinema avant-garde and referred to as “one of the most beautiful Soviet films.” Alone, accompanied by an orchestra playing the restored music by Shostakovich (the then sound record was highly inadequate), has been recently screened in France, U.K., and Holland.

In his book Prostranstvo tragedii (The Space of Tragedy), published after my father’s death, he recalls this expedition. “In order to reach the isolated spot in the mountains of the Altai we had to ride a long way along narrow paths. In 1930 we made the film Alone. It was then that I met Kondraty Tanashev. He was a professional shaman and knew his business. He worked on real fuel, never free-wheeling: an epileptic, he knew the signs, how to take advantage of an oncoming fit. Besides that, he was an inveterate drunkard.”

“He was a professional shaman”

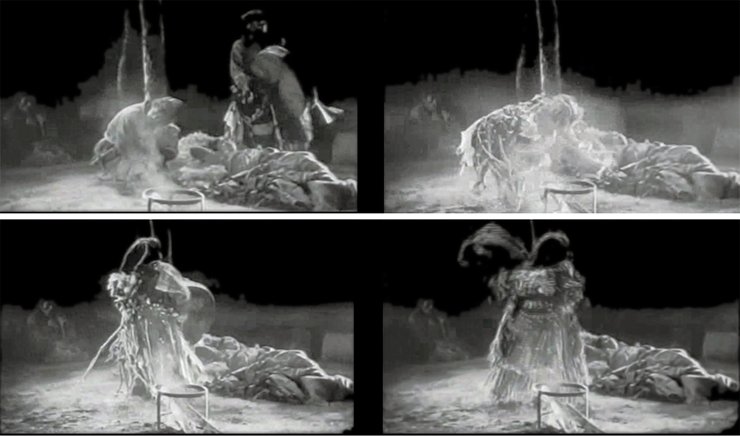

“He used to heal sick children before my very eyes in the dark, smokey yurt. He would strike his drum with a tampon, wail, intone some sort of incantation in a husky voice and then leap up, twirl round and round, stamping his boots. He had a good sense of rhythm. Accelerandos, unexpected pauses, syncopation – he knew how to use them all. The big drum was made after the ancient models; inside the rim on the cross-piece was carved the dark wooden head of the god Ulgen with iron eyebrows and nose and copper bells. Tanashev alternated between striking the leather, tightly stretched over the rim, with sharp taps, and shaking the drum so the bells rang. Sewn on his sheepskin were long narrow rags with some shrivelled rubbish (frogs or tiny creatures) on the ends. When he spun round, the ribbons unwound, the hearth flared up from the movement, the yurt filled with smoke, it became difficult to breathe, one’s eyes smarted, but the shaman speeded up the rhythm of his movements, struck the drum more frequently, everything clanged, jingled, and you could hear coarse cries. And suddenly Tanashev would fall to the ground, as if mown down, his body would writhe in the throes of a fit (real or simulated), his eyes would protrude and his mouth froth.

We had come there to laugh at his performance. However we were in no mood for laughing.

We took Tanashev to Leningrad to film him in the studio. He obligingly repeated (several times) the whole gamut of his incantations. Nothing of their power came over on the screen. There was nothing for it but to ride for five days, to catch sight of the decaying horse-hide on the pole at the entrance to the yurt (knowing that it had been skinned from a live horse), to sit with smarting eyes, with a sick child lying on a rag, the eyes of his mother watching the epileptic drunkard with alarm and hope.

The horror did not at all lie in the ritualistic rhythms and the magic incantations.

Tanashev’s adaption to civilization was sad: he became a complete alcoholic and I do not think he successfully completed his career on returning home.”

The fate of the drum

Tanashev’s drum went to my father and occupied an honorable place in his study for 80 years – 43 years until my father’s death and another 37 years until my mother’s death. Whether my father got it from the Selsoviet (village Soviet), or Kondrat himself gave or sold (drank away, to be more exact) it to him I don’t know. Given the overall picture of those years, this act would not look too blasphemous. In the 1920s, shamanism in the Altai blossomed but when collectivization started, the Altai natives began to abandon their faith in great numbers. They stopped sacrificing domestic animals and hang their hides on poles (such a hide with a skull – taelga – is an impressive symbol of the old world in Alone). Drums were handed in to village Soviets; some of them made it to museums while others were destroyed.

This musical and ritual instrument was kept at the home of the well-known director Grigory M. Kozintsev. In 1930, he was making his film Alone in Gorny Altai, where he met Tanashev, an unusual person and adventurer, in a sense, but undoubtedly talented. The director invited Kondrat to Leningrad and shot the episode in which the shaman was beating the drum. The very drum. This was the shaman’s winged horse. Speeding it with its whip-tampon, the shaman traveled across the worlds: up to the sky and down to hell. Attached to the drum’s handle is the wooden head of Ul’gen’, Altaian supreme deity, who grants people the gift of becoming a shaman; on the exterior there is a drawing: the sun, stars, rainbow, and a vertical symbolizing the world tree or a horse line – the Universe in miniature.

Having stayed with Grigory Kozintsev as a souvenir of the filming, the drum held pride of place in his study. And now, eighty years later, it has come back from the banks of the Neva to Siberia.

The son of the director, Doctor of History and Senior Researcher at the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) Alexander G. Kozintsev has donated the drum to the Novosibirsk Museum as he believes that this is its proper shelter

“My best regards and respect to dear comrade Maksim Grigorievich Levin,” wrote Tanashev (NB: wrote!) to our prominent ethnographer and anthropologist on his return from Leningrad in May 1930. “I am free from the expedition now… The trip went well and was successful. I am now at home and have begun gathering some texts for you... The drum I had promised you was burned during the extremities at the Ust-Kan aimak on the order of the village Soviet chairman… So it goes with these people, they have done a lot here.”

So the person who posed as a savage and insane minister of an ancient cult not only wrote letters in Russian but had a wide circle of scholarly acquaintances in both capitals. In one of his letters (they are stored at the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography archives) he inquires after V.G. Bogoraz’s health and sends him his best wishes.

Whether Tanashev lied, as was customary with him, or another drum is meant I have no idea. The last sentence is oblique but there can be no doubts as to the “extremities” and “have done a lot.” Note, by the way, how sensitive Tanashev was to the new phraseology. One of his notes obviously written in the state of a heavy intoxication is virtually incoherent delirium, and yet it abounds in clichés like “life in our wild country,” “proletarian blood,” “oppressed people of the entire world,” etc. The note ends with a reference, “as said comrade Potanin and other old academic comrades with whom I had a brotherly and c(omradely) struggle in my savage native country…”

One way or another, with an 80-year delay, this drum too has made it to the museum. Who then was its remarkable owner?

“An amazingly parasitic specimen”

Tanashev is a legendary figure; there is a lot of evidence about him. The personality emerging out of it looks different from what my father depicts. Except for one thing – drinking. Though Kondrat mentioned his epilepsy to ethnographers as well, my father’s words about the fit “real or simulated” sound appropriate. There is no other evidence to support the disease claim, and L. I. Potapov – our top authority on Altai shamanism – writes that shamans were not epileptics; in fact, they fully controlled themselves. Kondrat was a talented hoaxer and a skilled actor. He said and did what his role required, fooling not only my father but ethnographers, too.

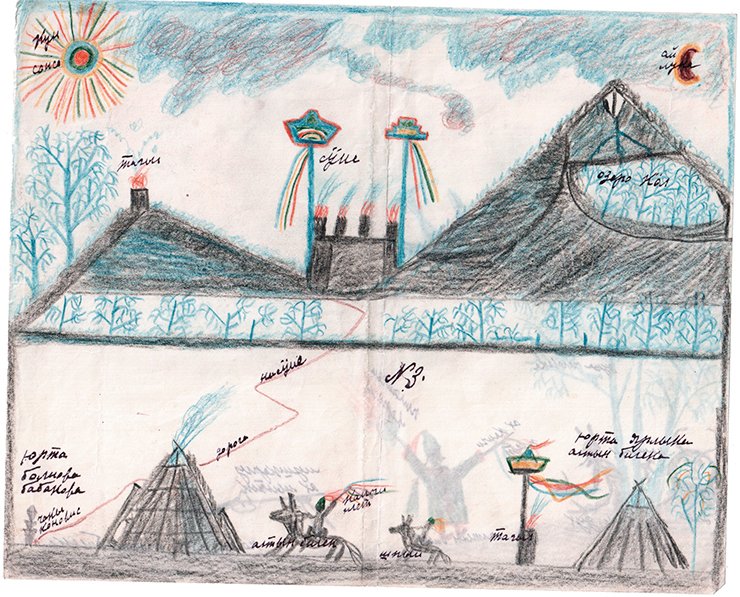

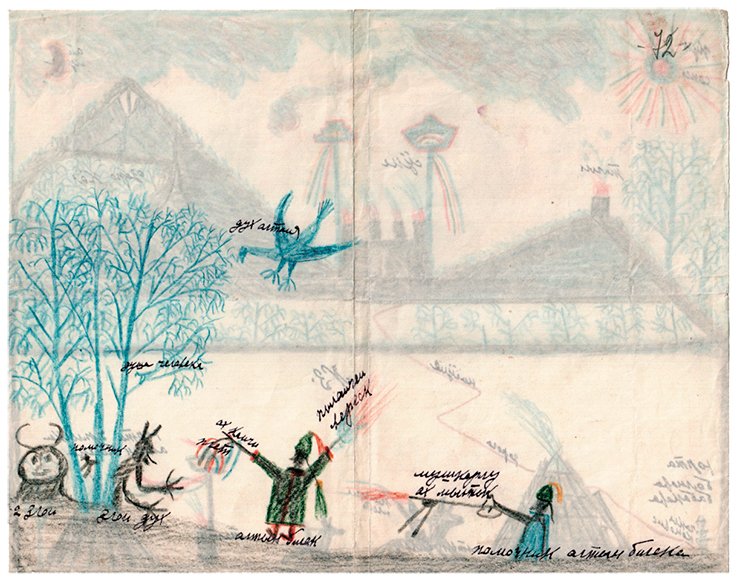

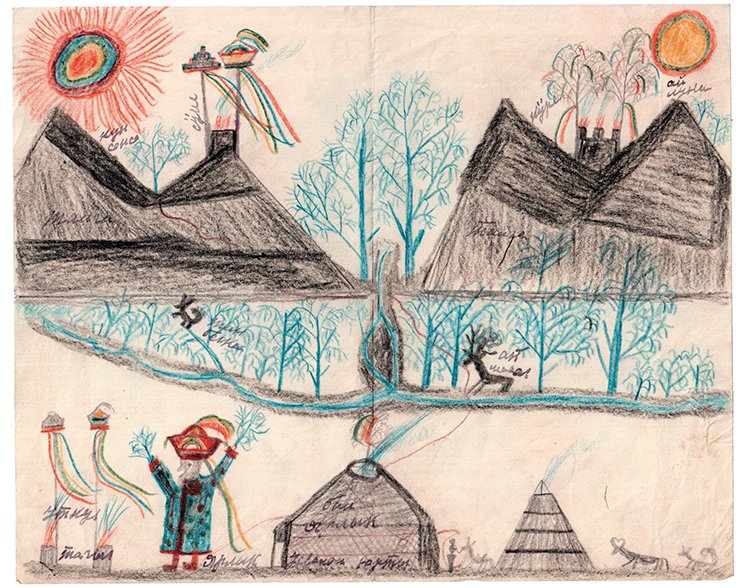

In 1935, a research worker at the RAS Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography L. E. Karunovskaya published a large article on the Altaic image of the universe. The paper was based entirely on Tanashev’s stories and drawings. S. A. Tokarev and L. P. Potapov – prominent ethnographers who later collected abundant data on Altaic shamanism – stated that the information supplied by Tanashev was unreliable. For Karunovskaya herself, Tanashev’s slyness was not a secret either. Her husband A. G. Danilin, a researcher with the ethnographic department of the Russian Museum, who had worked in the Altai together with her collecting materials for a book on another Altaic religion – Burkhanism – also drew heavily on Tanashev’s texts, including autobiographical ones.

“In his autobiography,” writes Danilin, “Tanashev reveals one of the negative sides of his nature – cunningness. Knowing that materials on Burkhanism were gathered to be published, he made up his autobiography so as to produce the impression that he was almost a revolutionary or, at any rate, an active assistant to the Soviet power. Examination of the facts, however, detected that they were partly adjusted and exaggerated, partly fictitious.” Having critically analyzed everything he had heard, Danilin wrote Tanashev’s biography, which we will now render in brief.

Kondraty Ivanovich Tanashev was born in 1885 to the family of an Altaian hunter. His first name was Merei. He grew up in a Russian milieu, and from five years on was able to speak Russian well. In the beginning of the century he was baptized and got the Christian name of Kondraty. He taught himself to read and write. In 1904 in Biysk he met G. N. Potanin, who supplied him with illegal literature. In the same year, after the crackdown on Burkhanists by the authorities and Russian peasants, he recanted Orthodox Belief, adopted the “White Belief” and became a yarlyk (Burkhanist preacher). He traveled all over the Altai, preached the new religion, sang songs of his own making, and alleged that Burkhan had cured him of the right hand paralysis. His name became well known. He got imprisoned. Upon the release, he continued his struggle against Russians – this time, as a Shamanist. He was reputed to be a “powerful shaman.” However, according to Danilin, while being both a Burkhanist and Shamanist, Tanashev believed neither, he just made a living by religious practices. “He is a highly unstable person, ambitious and at the same time foolhardy” (Danilin implies struggle against Russian missionaries). Nevertheless, before the First World War our hero was repeatedly baptized and even became a deacon.

In 1915, Tanashev, together with other Altaians, was dragooned for a work crew in the rear (Chernigov province). People were loading railway cars with coal in unbearable conditions but Kondrat did not break his back – he worked as a foreman and interpreter for the authorities. Also, he wrote letters for the illiterate, who paid him back by doing physical work for him. After the revolution, he was elected a workers’ delegate and attended conferences in Petrograd, in Tauride Palace. On the Soviet of Workers’ Delegates’ assignment, he traveled to towns of European Russia, looking for those who went missing during rear works. On his return, he fought for the Reds, escaped from them to Mongolia, then came back… In 1925 he supposedly made a break with Shamanism and handed in his drum (it made to the RAS Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography). According to another version, the drum was taken from him by a politprosvet (Political Education Council) instructor since Tanashev was going to join the Communist Party. Kondrat became involved in action against illiteracy, propagandized Socialist construction but stealthily continued performing shamanist rituals. In 1929, he cut off his plait in public and announced: “If I go on practicing shamanism and deceiving people, cut off my head as I have just cut off this plait!” But this was yet another trick.

It was at that time that the paths of my father and Tanashev crossed. He came to Leningrad, where he kept playing the role of the shaman in Alone, only this time in a Lenfilm studio. He was staying in a hotel, drinking heavily, and was regularly taken away by militia. Having returned home, he worked for an agricultural cooperative association, at a deer breeding sovkhoz (Soviet farm) and at gold mines, lived on hunting, then became a driver on the Chuya postroad – drove sheep from Mongolia to the Altai. In a word, an accomplished gentleman of fortune, though talented and out-of-the-ordinary.

“An amazingly parasitic specimen,” writes L. E. Karunovskaya in her logbook. “They say he was as active under the Whites as he is now; he goes all out about ‘Soviet socialism’, but should the Whites come back, he would be just as zealous. At home, his family works for him – his 70-year-old mother, his step-father, also of advanced years, and kids whereas he himself gads about and drinks… He is extraordinarily flexible. A diabolic face with sly, evasive eyes… As a former shaman, he is feared – as a result, he is used to undeserved attention and gifts…” Tanashev was called a con artist and a swindler by the Siberian writer A.L. Koptelov, who knew him personally.

The last thing Karunovskaya remembered as she and Danilin were leaving Yabogan was drunk Kondrat waving a red flag in their honor.

Nothing more to say… And yet, let us try to look at Tanashev at a different angle. Speaking about his personal traits, let us not forget that, together with his people, he went through the mayhem. Gorny Altai was the cockpit of four cultures: Shamanist, Burkhanist, Orthodox, and Soviet. How could one survive in this whirl? True, it was time-serving that always helped Tanashev out. On the other hand, people believed him as a shaman, Burkhanists respected him as a preacher and sang his songs. Deception? But then what does “truth” mean with regard to religion?

Nothing more to say… And yet, let us try to look at Tanashev at a different angle. Speaking about his personal traits, let us not forget that, together with his people, he went through the mayhem. Gorny Altai was the cockpit of four cultures: Shamanist, Burkhanist, Orthodox, and Soviet. How could one survive in this whirl? True, it was time-serving that always helped Tanashev out. On the other hand, people believed him as a shaman, Burkhanists respected him as a preacher and sang his songs. Deception? But then what does “truth” mean with regard to religion?

Speaking about the “apocryphal” nature of his texts, let us ask ourselves: how is folklore created? Only through mechanic reproduction? If we look at Tanashev as a man of folk culture, he differs from its ordinary representatives only in his extraordinary talent and resolution with which Tanashev, a carrier of living tradition, dared to alter it. Why cannot he be considered a maker of folklore? Hence, Karunovskaya and Danilin were right when they wrote down and studied his texts. Are they “less truthful” than, say, The Kalevala compiled by Lönnrot? Ordinary carriers of tradition can only reproduce it whereas the most talented, who are always exceptionally few, alter and create it.

In his endless shift, ingenuity and ability to take many shapes Tanashev looked like a mythological trickster – this is yet another tie with folk and even archaic culture. During the rituals, he demonstrated typically trickster-like hocus-pocus like “spewing out stones” or “swallowing” big bells, which he in fact put in his bosom. There is an age-long world tradition behind it. Folk performance art is both religious and burlesque; it does not fit in the schemes invented by pedantic scholars. By the way, this art was congenial to the founders of cinema avant-garde. It’s a pity that back then, in 1930 in the Altai, this affinity was overlooked, obscured by politics and topics of the day.

As years go by, researchers may become a bit more charitable towards both Kondrat Tanashev and his art. And his drum, which has taken a worthy place in the Museum of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography SB RAS, will become one of the countless links between yesterday and today.

References

Diakonova V. P. K. Tanashev: an Altaian yarlykchi or a shaman? // Lavrov (Central Asian and Caucasian) Memorial Conferences 1996—1997. St Petersburg: isd-vo MAE RAN, 1998. P. 132—134.

Karunovskaya L. E. The Altaian image of the universe (materials on Altaic Shamanism) // Sovietskaia etnografiia. 1935. Iss. 4—5. P. 160—183.

Kozintsev G. M. King Lear: the space of tragedy. Translated by Mary Macintosh // London: Heinemann, 1977. 260 p.

Potapov L. P. Altaian Shamanism // Leningrad: Nauka, 1991. P. 302—303.

Tokarev S. A. Remnants of the Altaian totemic cult // Trudy Instituta Etnografii AN SSSR. New series. 1947. V. 1. P. 139—158.