The map of Russia's Northern Shore of 1612 by Isaak Massa and The Book of the Great Map of the Moscow State

The outset of the Russian-Dutch relations in publishing business and book trade dates back to the end of 16th century. In the early 17th century, detailed maps of the Russian territory were first published in Holland. What were their sources and principle? The concern expressed by many scholars that The Old Map of the Moscow State and The Great Map of 1627 perished without from the maps that made part of The Old Map of the Moscow State. This is how the map of Russia's northern shore delivered by merchant and traveler Isaak Massa to Holland became the first publication of the Russian manuscript route maps. A hundred years later, Dutch specialists invited by Peter I to the Russian service contributed greatly to the development of Russian cartography, and Dutch publishers supplied books to the library of Peter the Great, and later to the library of the Academy of Sciences

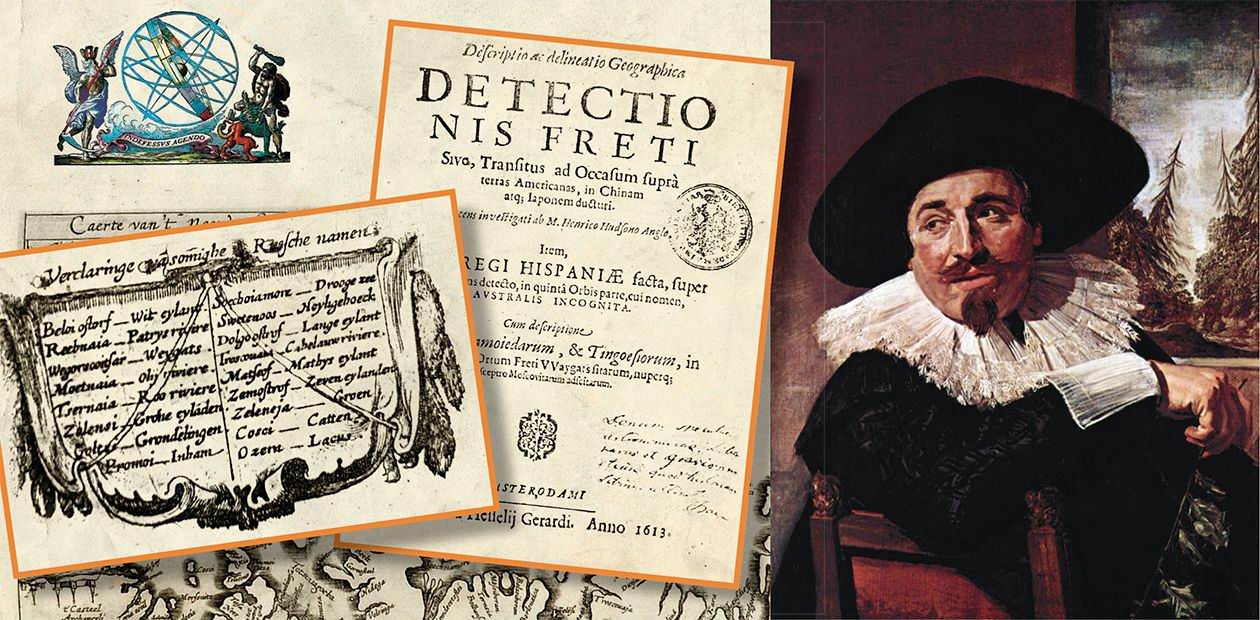

In 1612 in Amsterdam, the geographer, cartographer and publisher Hessel Gerritsz issued a collection of articles headed Beschryvinghe Vander Samoyeden Landt in Tartarien (Description of the Samoyeds’ Land in Tartaria), which included two articles about Siberia written by the Dutch merchant and traveler Isaak Massa. One of them was about the conquest of Siberia and trade with the indigenous population started by the Stroganoffs; the other gave a brief account of the routes leading from Moscow to Siberia, rivers of the Russian North-East and a list of Siberian towns set up by the Muscovites1. Enclosed to the articles was a map of Russia’s northern shore with the following inscription on the top: “Caerte van’t Noorderste Russen, Samojeden ende Tingoesen Landt: also dat vande Russen afghetekent en door Isaac Massa vertaelt is”, i.e., “The map of northern Russia, Samoyed and Tungus lands and the part of Russia Isaak Massa related”. Massa’s articles became a true discovery for western readers and were promptly translated to many European languages. The important new map of the vast cold ocean attracted a lot of attention as well. For a long time, scholars have wondered about the map’s origin and its sources. Now, we can finally solve this problem.

The man who brought the map to Europe, Isaak Massa, was a descendant of rich Italian traders, who moved to Holland at the very beginning of Reformation, and a Calvinist in his beliefs. He was born in Haarlem in 1587. According to Isaak’s story, in his childhood he failed to get not only systematic education but any education at all, and the thorough knowledge acquired later he owed entirely to himself. By his parents’ wish, Isaak began living on his own quite early. At the age of 14, he was sent to Russia to study commerce. There, Massa took an interest in the Russian North-East, among other things – firstly, probably, as a sales and raw material market and also as an area opening a trade route to China. However, the extensive geographic and ethnographic data he collected and subsequently published betrayed him as a person with a bent for Earth sciences, in historian M. P. Alekseev’s apt words. Massa spent eight years in Moscow, was witness of the famine of 1602 and was in Russia at the Time of Trouble, which made him leave Moscow in 1609 and return home through Archangelsk. A few years later, Massa came back to Russia as an ambassador of the States General and, doing diplomatic errand for his government, traveled a lot between Moscovia and Holland. His last visit to Moscow was in 1633—1634. In spring 1635, Massa welcomed the Tsar’s embassy in Amsterdam and participated as an interpreter in the negotiations with the States General. This must be the last thing known of him. He died in 1643, at the age of 57. After his first coming back from Russia in 1610, while his impressions were still vivid, he wrote memoirs entitled “Een coort verhael van begin en oorsprongk deser tegenwoordige oorlogen en tpoeblen in Moscobia, totten jare 1610 int. Cort overlopen ondert gouvernement van diverse vorsten aldaer” (“A brief note on the beginning and origin of modern wars and trouble in Moscovia that occurred before 1610 in a short period during the rule of several sovereigns”) and presented it to Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange, but a long time passed before this manuscript was made public. At the same time he put forth in two articles the data he had on Siberia. The destiny of these works was more fortunate: both the articles and the map agitated European readers at once.

“The map of Northern Russia, Samoyed and Tungus lands and the part of Russia Isaak Massa related”

The map of Russia’s northern shore covers a huge space: the northern part of the Kola Peninsular, European coast of the Russian North, Yamal and Gydansky peninsulas, and part of Taimyr to the River Piasina estuary. In the left-hand corner of the map there is a small vocabulary – Verclaringe va Somigne-Russche namen – giving Dutch translations of some Russian geographical names: Beloi ostrof – Wit eylant, Reebnaia – Patrys riviere, Wegorscoitsar – Weygats, Moetnaia – Ohij riviere, Tsernaia – Roo riviere, Zelensi – Grone eylanden, Goltsi – Grondelingen, Promoi – Inham, Soechoiamore – Drooge Zee, Swetenoos – Heyligehoeck, Dolgo ostrof – Lande eylant, ...Matseof – Mathys eylant, Zemostrof – Zeven eylanden, Zeleneia – Groen, Cosci – Catten, Ozera – Lacus.

This shows that Isaak Massa drew on Russian sources to construct his map, and the author himself confirms this hypothesis: “At that time a brother of a friend of mine lived in Moscovia and took part in these discoveries in Siberia; this friend passed me over the map narrated to him by his brother, now dead, and drawn by him; my friend himself has sailed through the Bay of Vaigach and knows all locations up to the Ob; as for the lands beyond this river, he learnt about them from the others.”2

So this was a source of data on the eastern segment of Massa’s map. It remained unclear though what the sources of its western and central segments were and when they were constructed. In the meanwhile, this map, for a long time the only map of North-East Siberia, had always riveted a lot of attention.

As for the dates of the Russian source of this draft, two opinions have existed for long. Academician J. Gamel writes: “…the map constructed in Moscow, probably in 1604 and certainly no later than 1608 and printed for Massa with Dutch inscriptions.”3 Historian J. Keuning agreed with Gamel and made the following comment: “… positively, after 1601 since it shows the Taz town (also called Mangaseya) on the eastern bank of the river Taz, founded this year.”4

The Book of the Great Map and Dutch cartographers

Of special interest for us is the fact that many of the geographical names found on this map are clearly related with The Book of the Great Map (“BGM” hereinafter), which describes the so-called “Old Map” of the Moscow state. When, in the second half of the 20th c., many previously unknown archival documents became accessible to scholars, historian B. P. Polevoi, who studied this issue, realized that The Old Map of the Moscow State was not a big wall draft, contrary to the earlier hypothesis (one map could hardly have encompassed the BGM rich content), but the so-called “map book”, a set of cartographic documents prepared during the reign of Boris Godunov in 1598—1601, and it contained: 1) a general map, comparatively small in size, that covered the entire territory of the Moscow State and the “fields” (lands from Moscow to the Crimea); 2) a map of Moscow constructed on purpose for The Old Map of the Moscow State; 3) a plan of the Kremlin with Russian inscriptions (showing all the houses occupied by Godunov’s relations) published later, in 1662, by a most outstanding cartographer and publisher V. Blau; 4) a series of route “particular” maps, mostly of rivers and roads, whose relationship was shown on the general map; 5) special “descriptions” in cases when there were no route maps.

This dramatic change in our understanding of the structure of the maps described in the BGM happened, in the first place, after publication in Haag in 1958 of The Atlas of Siberia by Semyon Remezov, referred to in the literature as the Horographic Book5, which is a set of route maps. Shortly after this publication, a few similar route maps of the 17th c. showing the rivers of Siberia were reproduced in The Atlas of Geographic Discoveries in Siberia and North-Western America6. It became clear hence that in the 17th century maps of single rivers and roads were the most common type of cartographic documents, usually supplementing the general maps. Descriptions of these travelling maps of rivers and roads constituted the main content of the BGM. This principle underlay The Old Map of the Moscow State, The Godunov Map of 1667, N. G. Spafariy’s report map of 1675—1678, and Semyon Remezov’s Map of Part of Siberia of 1697.7

The Old Map of the Moscow State was kept at the Moscow Kremlin, in the building of Razriadny and Posolsky Prikaz (Prikaz was an administrative or judicial office in 15th-17th century Russia; Razriadny Prikaz was in charge of military management and boundary cities of the Russian Tsardom, and Posolsky Prikaz was in charge of international affairs) shown in the shape of letter «П» on the “Kremlin town” map, which was one of the documents contained in the first part of The Old Map mentioned above. During the Moscow fire of May 1626, the building was destroyed by fire, but some books are known to have been saved, and the book of The Old Map was definitely one of them. After the fire, a list of the things that survived was compiled, and a massive and complicated effort was made to restore the old documents ruined by the fire; at the Razriadny Prikaz too, a register of the files saved from the fire was drawn up. It was then that they began retracing The Old Map… of the Entire Moscow State, which survived the fire but was all “tousled” and “fell apart” because of long use. The Duma clerks Fedor Likhachev and Mikhail Danilov ordered the draftsman of the Razriadny Prikaz Afanasiy Mezentsev to construct a new map of the Moscow State and to write a description for it, which was done in the fall of 1627.8 This description, or The Book of the Great Map, is a successive description of maps and “particular” drafts that constitute the “map book” of The Old Map of the Moscow State.

As time went by, traces of the maps of the Moscow State were lost, but different libraries and private collections carefully preserved manuscripts of The Book of the Great Map9, an invaluable geographic monument of medieval Russia. Since the mid 19th century, numerous attempts were made to restore, on the basis of the BGM text, “the ancient geographic map of Russia and adjacent countries. ”In 1852 the Ethnography Department of the Russian Geographic Society put forward this task at an open all-Russia competition. The only (!) work submitted by a certain G. S. Koulikovsky turned out to be unsatisfactory.10 Later, a member of the Ethnography Department E. K. Ogorodnikov presented three solid works dedicated to BGM’s separate parts, two of which concerned Russia’s northern shore, The Murmansk and Tersk Shores according to The Book of the Great Map (St Petersburg, 1869) and The Arctic Sea and the White Sea Coasts according to The Book of the Great Map (St Petersburg, 1875).11

Karl Baer was one of the first to put forward the hypothesis that underlying the foreign maps of the Russian territory, in particular the map by Hessel Gerritsz published in 1613—1614, were data found in The Old Map of the Moscow State described in the BGM. He supposed that Massa had kept a copy of The Book of the Great Map.12 According to Ya. V. Khanykov, known for his cartographic works, Baer believed that Massa also had a manuscript of The Book of the Great Map. Baer’s hypothesis was later supported by other scholars (V. A. Kordt, N. D. Chechulin, S. M. Seredonin) and now it is corroborated by the woks of B. P. Polevoi.

How Isaak Massa used The Book of the Big Map

Let us test another hypothesis: is Isaak Massa’s map of Russia’s northern shore drawn up in 1612 a reflection of the route maps described in the BGM?

Corresponding to the western part of the coast shown on Isaak Massa’s map is the description from the BGM “Along the seashore from the River Onega estuary the River Dvina estuary, the rivers that flow into the sea.”13Comparisons of the route map description and the respective part of the shore show that virtually all the geographical names coincide. For some areas of the Dvina estuary, Massa’s map is even more detailed: names of all four branches of the estuary are given whereas the BGM only states that “the River Dvina flew into the sea in four branches spread over 50 versts” (1 versta is 1.0668 km). Undoubtedly, the explanation of this difference is that in 1609, as Isaak Massa was traveling back from Moscow to Holland via Archangelsk, he sailed along the Dvina and the Sukhon rivers and could thus verify the location of many geographical features and map them. This is clearly seen on the map of Russia published by Hessel Gerritsz, first issued in Holland in 1613. The draft, basing on which Gerritsz constructed his map, also came to him from Massa.

Description of the next map contained in the BGM, “From the River Dvina estuary by seashore to the east, the rivers that flow into the sea” covers a vast expanse from the Dvina to the River Kara. One can see that despite recent colonization of these places by the Russians, Russian geographical names had almost completely replaced local names.14 Interestingly, the name Coski (“cats” in Russian), referring to two small islands in the White Sea, is given in the vocabulary placed on the map (mentioned above) and translated by Isaak Massa as “Catten”.15 In the bay in front of the Pechora estuary, the same as close to the Dvina estuary, we can see the “Dry Sea,” Soechoia more, which must have been well-known to the seafarers.16

In the space between the rivers of Pesha and Kara, inscriptions on Massa’s map are misplaced. The straits in this locality are known to be referred to as Shar, and the inscription “Mesoetsar”, corresponding to a strait, happens to be next to an island. The BGM contains no names of the strait estuaries, but it can be assumed that they are Verhniy Shar and Niznniy Shar17 (“Mesoetsar” is Smaller or Small Ball; “Bolsoitsar” is Big Ball). Further on, from the Pechora to the Korotaeva River, of greatest interest is the River Petsianca Borloyauca, which reads as Peshchanaya Bourlova in the BGM. As a matter of fact, these are two different rivers: the Peshchanaya and the Bourlova (Ogorodnokov, 1875, p. 217), or the Bourlovaya and the Peschanaya (archimandrite Veniamin, p. 88). The River Peshchanaya flowing in this locality is also mentioned by F. P. Litke.18 The fact that this serious error on Massa’s map is also found in the BGM is a strong argument in favor of the hypothesis that underlying the map of Russia’s northern shore were the route maps contained in The Old Map of the Moscow State.

Further eastwards, description of this locality in the BGM becomes unexpectedly schematic and so succinct that we can quote it here in full:

“From the Kara River three rivers flew into the sea, and no names of these rivers were inscribed on the old map.” (The BGM states that the rivers were depicted but without names.)

“From these rivers, beyond the bay, the River Kniazkova ran into the sea; from the Kara River to the Kniazkova is 120 versts; the Kniazkova River length is 170 versts.

From the Kniazkova River to the Nyriamshoi Bereg near the sea is 200 versts.

From the Nyriamshoi Bereg to the river Ob is 130 versts.

Behind the River Ob is the River Taz, and falling into it is the River Pur.

And on the rivers Taz and Pur is Mangaseya”.

There is no discrepancy between this description and Massa’s map. Firstly, both the BGM and Massa’s map deal with the same territory: the route map covers a much wider area: previously, the BGM and Massa’s map showed only river estuaries and coastal towns, and now, to the east of the River Kara, the Ob tributaries and the cities of Tobolsk and Mangaseya are plotted.

What is the explanation for a more detailed description of this area in the BGM as compared with Massa’s map?

The BGM was constructed in 1627, and in August 1623 the Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich issued a decree that the sea route to Mangaseya be replaced with the land route, via Kamen’ (Urals), and the sea route was banned under pain of “deep disgrace and execution.” Therefore, we can suppose that evidence of this route was intentionally taken out of the maps and BGM. Let us try to understand why this happened.

At the time The Old Map was constructed, this way had long been well known to the Russians.19 It is described in detail in the note written by the Tobolsk commanders of Matfei M. Godunov, prince Ivan F. Volkonsky and clerk Ivan Shevyrev on the interrogation of the “trade” man Levka Ivanov Shubin: “‹…› last year, that is in 109 (1601), Levka and his friends went… And they came to Mangaseya. ‹…› “Trade and industry people said that they had gone from the Pinega and Mezen and the Dvina by sea… to Mangaseya to pursue their trades for twenty and thirty years and longer than that to Pustoozero and the Kara Arc, to portage.”20 Naturally, it can be assumed that this way could have been depicted on the route map which made part of The Old Map set of maps.

Possibly, it was the publication of Isaak Massa’s map of the Russian northern shore in 1612 and 1613 and the appearing in print of a detailed description of this route drawn from the Russians by Muscovi Company agents that resulted in 1614 in the correspondence between the Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich and Tobolsk commanders concerning “taking action that would prevent German people from finding out the way to Siberia.” The Moscow authorities had more than one reason for anxiety: “so that the Germans will not find out the route, and the military men arriving in Siberian towns will not cause damage because in Mangaseya and in other Siberian towns the people are few, and they cannot stand against many people…”21 And more importantly, “so that the treasury may not bear losses in tolls ‹…› because there are no cities or Prikaz clerks in these places… and if they go to Siberian and to Russian cities, the treasury will have double profit because they will have to go through the cities and show their goods together with their identity papers.”22

Since the new map and BGM were constructed after the decree of 1623 prohibiting both to the “Germans” and Russians to go to Mangaseya by sea (“in no way shall the Germans be allowed to go to trade in Mangaseya; and not only they but Russian people shall not go to Mangaseya from Archangelsk town either so as the Germans looking at them will not find out the way…”23), it is highly probable that evidence of the sea route to Mangaseya could have been removed on purpose, which is confirmed by the comparison of the BGM schematic description and Massa’s map: it is the description of the route shown on the map that is missing!

From “good connections with Prikaz clerks” to the first publication of the Russian manuscript route maps

It would be appropriate to remember here that Isaak Massa, when in Moscow, had good connections with Prikaz clerks and courtiers; besides, he learnt the Russian language and had such a good command of it that he managed to translate from Dutch to Russian the story of Prince Maurice victories. It is notable that the heading of the first Dutch edition of I. Massa’s narration about Siberia goes, “Description of Samoyeds’ land in Tataria, recently annexed to the Moscow State, translated from Russian in 1609…” (see M. P. Alekseev). The above-said implies that just as underlying Hessel Gerritsz’ map of Russia of 1613—1614 was the approximate Old Map of the Moscow State, underlying Isaak Massa’s map of the Russian North were the route maps of Russia’s North described in The Book of the Great Map. To check this hypothesis, we conducted comparison of the geographical names on Massa’s map and in the BGM text.

Undoubtedly, descriptions of the route maps “Along the seashore from the River Onega estuary the River Dvina estuary, the rivers that flow into the sea” and “From the River Dvina estuary by seashore to the east, the rivers that flow into the sea” and the respective part of Russia’s northern shore on Isaak Massa’s map look very similar. Isaak Massa himself confessed, “I will describe, as far as I possibly can, the way from Russia to Siberia but I have to say that I could not find out more. What I know I have collected with great effort thanks to my friendship with certain persons of the Moscow court, who entrusted me with this evidence because I happened to be in their good graces, though they hesitated for a long time before giving it to me. This could have cost them their lives because the Russian people are extremely distrustful and cannot bear someone disclosing the secrets of their country.” Insignificant discrepancies must be attributable to the fact that when Massa finally got access to the documents he was interested in (The Old Map of the Moscow State, in this instance), he made copies in great haste, which is why he plotted the River Golubitsa twice, put the name of the strait mouth Menshoy Shar next to an island, and showed two rivers, the Peshchanaya and the Bourlova, as one. At the same time, he added to the map some interesting details, for example, charted the names of all the four estuaries of the River Dvina, probably after his voyage down the Dvina to the White Sea. It is noteworthy that the historian Keuning, who agrees that Massa used Russian sources to construct his map, draws attention to the fact that he did nothing to change the Russian version of the map except giving Russian names in Latin. Massa did not even take into account the Dutch exploration of Novaya Zemlya!

This is how the map of Russia’s northern shore delivered by Isaak Massa to Holland became the first publication of the Russian manuscript route maps. This is another confirmation that the concern expressed by many scholars that The Old Map of the Moscow State and The Great Map of 1627 perished without any trace was in vain: the Dutch maps studied recently have evidently borrowed a lot directly from the maps that made part of The Old Map of the Moscow State.

References

1 Alekseev M. P. Siberia as reported by foreign travelers and writers. Irkutsk, 1941. P. 252. This work contains the translated articles by I. Massa: I. Conquest of Siberia (P. 256—263); II. Brief description of the routes and rivers leading from Moscovia to the east and north-east, to Siberia, Samayedia and Tungusia, constantly traversed by the Russians, with further discoveries in the direction of Tataria and China” (P. 263—268).

2 Alekseev М. P. Siberia as reported by foreign travelers and writers. Irkutsk, 1941. P. 255; Kordt V. A. Materials on the history of Russian cartography. Second series. Issue 1. Maps of all Russia, its northern areas and Siberia. Kiev, 1906. P. 16—17; Bagrow L. A History of Russian Cartography up to 1800 / Henry W. Castner (ed.). Wolfe island, Ontario, 1975. P. 51; Keuning J. Isaak Massa. 1586—1643 // Imago Mundi. 1953. X. P. 68.

3 Gamel J. Ch. The English in Russia in the 16th and 17th centuries. The second article. St Petersburg, 1869. P. 208; Hamel J. Tradescant der Alter in Russland. St. P., 1847. P. 2, 230.

4 Keuning J. Isaak Massa. 1586—1643 // Imago Mundi. 1953. X. P. 68.

5 The Atlas of Siberia by Semyon Remezov. Facsimile ed. with an introduction by L. Bagrows’ Gravenhage, 1958.

6 The atlas of geographic discoveries in Siberia and north-western America / Edited by A. V. Efimov. Мoscow, 1964. # 35—40. See: Polevoi B. P. Siberian cartography and problem of “The Great Map”. //Strany i narody Vostoka. 1976. # 18. P. 213.

7 Polevoi B. P. On the role of the Ethnography Department of the Russian Geographical Society in “The Book of Great Map” studies // Sketches on the history of Russian ethnography, folklore and anthropology studies. Мoscow, 1977. Issue VII. P. 51.

8 Khaburgaev G. А. Remarkable geographer of early 17th century. // Kurskaya pravda. 1955. Sept. 3; Uranosov А. А. To the history of assembling “The Book of the Great Map”// VIET. 1957. Issue 4. P. 188—190; Uranosov А. А. To the history of cartographic work in the Russian state in early 17th c.// TIIEiT. 1962. Vol. 42. Issue 3. P. 272—275.

9 Serbina K. N. “The Book of the Great Map” and its revisions // Istoricheskiye zapiski. Vol. 14. 1945. P. 133; Polevoi B. P. Siberian cartography and the problem of the Great Map // Strany i narody Vostoka. 1976. # 18. P. 218.

10 20th anniversary of the Emperor’s Russian Geographic Society. January 13, 1871. St Petersburg, 1872. P. 142—146, 154—157; Polevoi B. P. On the role of the Ethnography Department... P. 48.

11 The geographer and polymath V. P. Semyonov-Tian-Shanskiy made an attempt to return to the BGM studies in 1918, but a thorough success was achieved as late as in the 1950s—1960s.

12 Baer К. М. Peter the Great merit in spreading geographical knowledge about Russia and its neighboring Asian lands // Zapiski RGO. Book 4. 1850. P. 263.

13 The Book of the Great Map / prepared and edited by K. N. Serbina. M.; L., 1950. P. 158. Further BGM quotations are from this publication.

14 Ogorodnikov Ye. N. The Arctic and White Sea coasts with their inflows according to the Book of the Great Map. St Petersburg, 1875. P. 67.

15 The term “coska”, or “coshka”, stands for sea shoals dried by the ebb tide and partially or completely recovered with high tide. Academician A. I. Shrenk supposes it derives from the Lappish “cuoshk” (See: Shrenk A. I. Russian dialectal phrases in the Archangelsk province // Zap. RGО. Book 4. 1850. P. 135).

16 A similar term was described by Academician A. I. Shrenk: “Dry water is ebb tide or sea at the lowest water level which dries its low shore and shallows (See: Shrenk A. I. Russian dialectal phrases in the Archangelsk province // Zap. RGО. Book 4. 1850. P. 135).

17 Archimandrite Veniamin. On the Samoyeds. St Petersburg, 1865. P. 84—85.

18 Litke F. P. Four voyages to the Arctic Ocean aboard the military brig Novaya Zemlya in 1821—1824. М., 1948. P. 49.

19 The Russian Historical Library published by the Archaeological Commission. St Petersburg, 1875. Vol. 2. Note to # 254. Columns 1087—1091.

20 The Russian Historical Library published by the Archaeological Commission. St Petersburg, 1875. Vol. 2. Note to # 254. Column 1083.

21 The Russian Historical Library published by the Archaeological Commission. St Petersburg, 1875. Vol. 2. Note to # 254. Column 1056.

22 The Russian Historical Library published by the Archaeological Commission. St Petersburg, 1875. Vol. 2. Note to # 254. Column 1071.

23 The Russian Historical Library published by the Archaeological Commission. St Petersburg, 1875. Vol. 2. Note to # 254. Column 1056.