The Volcano Valley in East Sayan

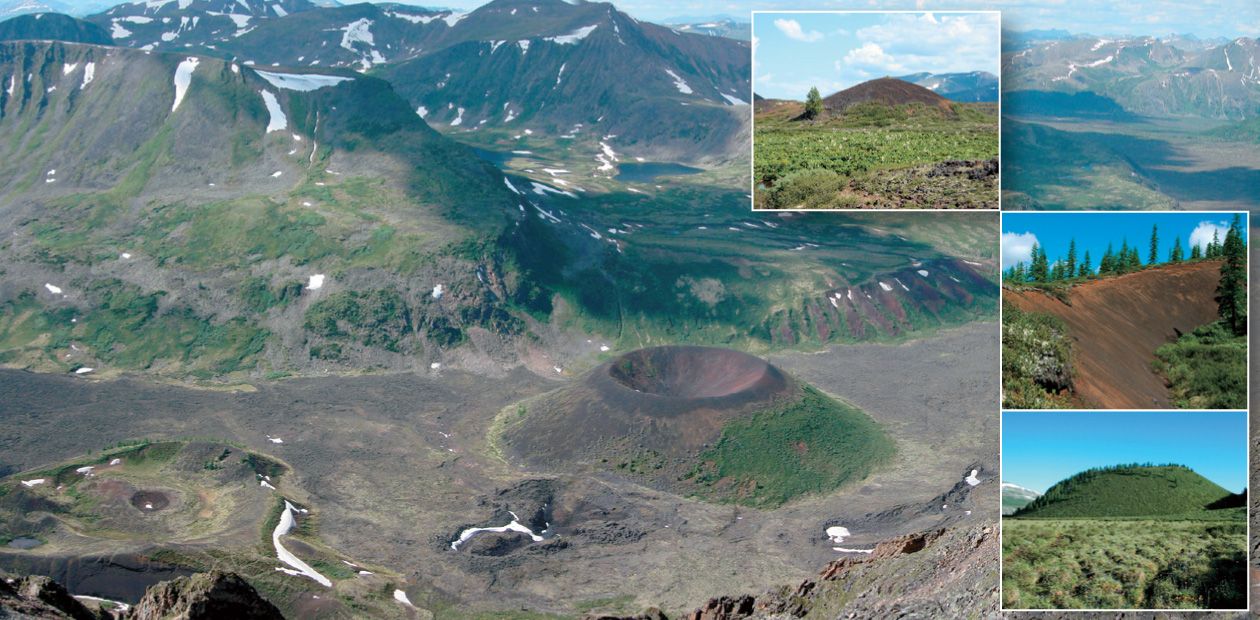

One of the most mysterious and beautiful nooks of Northern Asia is the Volcano Valley. It is located a short way off the City of Irkutsk, the capital of East Siberia. Everyone who gets to the center of the Sayan Mountains in the upper part of the Khi-Gol valley will see a miraculous view. Truncated cinder cones of volcanos, partly covered with trees, bushes, and mosses stand out against black or sometimes dark-brown lava. In past times, natives dared not rise up the valley, whose lavas and volcanos terrified them. It was believed that the lavas were the destroyed and melt palace of the fiend Gai-Dulman-Khan, who had been defeated by Gesar. At present, the Volcano Valley is popular with tourists, both Russian and foreign

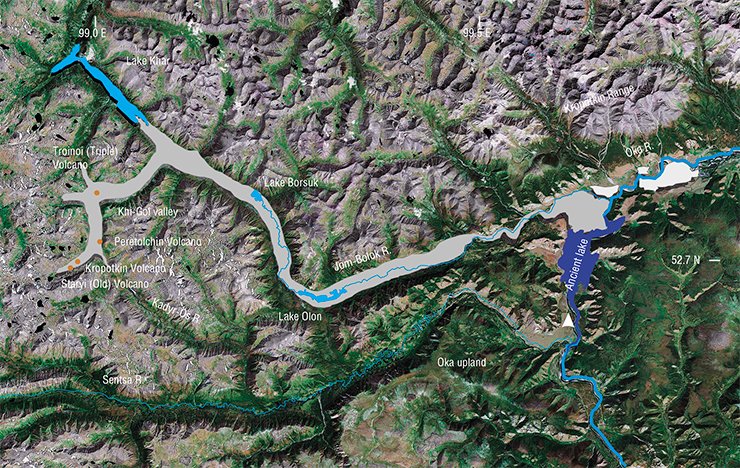

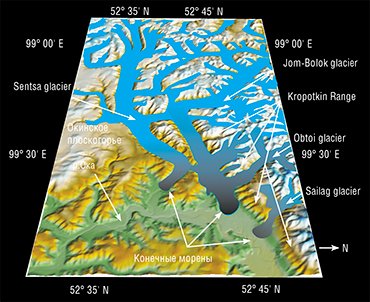

The Volcano Valley is an area of basalt flows of different ages, which form a continuous lava field about 70 km long and 150 m thick. The lavas that effused from crevices filled Khi-Gol, the large trough valley of the Jom-Bolok River, and, partially, the valley of the Oka River. The volume of the lava was so big that it could not flow down along the valleys and clogged the flow. As a result, basalts spread up the rivers emptying into the Khi-Gol valley and up the Jom-Bolok valley. After the effusion, the lava-dam Lake Khar (Black) formed in the upper reaches of the Jom-Bolok. Probably, its name was derived from the lava color. The lake is 11 km long and tens of meters deep. It is populated by fish species that had lived in the river before the volcanic dam formation and then evolved in isolation.

Another part of the valley is a group of cinder cones, located in the upper part of the Khi-Gol valley. The eruption was confined by a series of faults. Volcanos that formed there varied in shape. Classical truncated cones with internal craters are the Kropotkin, Peretolchin, and Staryi (Old) volcanos. Volcanos of the fissure type are Treshchina (Fissure) and Ostanets. In addition to the major volcanos 500–700 m in diameter, there are smaller cinder cones without craters, Pogranichnyi and Medvedev. Most of the volcanos are within the basalt lava field whose surface is formed by a heap of blocks of broken flow crust. Different investigators gave different names to the Jom-Bolok River: Dzhem-a-Louk, Zhun-Gulak, Dzhon-Balyk, Dzhon-Buluk, Dzhun-bulak, Zhan-Balyk, and Zun-Bulag. The Khi-Gol valley was formerly known as Khikushka (Obruchev, 1973).

Eight versts of “black stone”

The investigation of the Volcano Valley started with the examination of the Jom-Bolok by Egor Pesterev. He was a Russian land surveyor, who worked in the Irkutsk governorate from 1772 to 1781. His report of 1793 says, “The Zhun-Gulak River heads in high stony mountains, but at the very summit of those mountains there is a ravine looking like a valley, and that valley has no great forests or grass. Only black stone, looking like pig iron, stretches in an eight-verst-wide (TN: approx. 8.5 km) band. If a pedestrian has to walk along the stony ravine, he will have his boots torn up when coming to the opposite side because of the sharpness of that black stone, and if a piece of that stone sticks to a horse’s foot, the horse will immediately become lame” (cited from Obruchev, 1973, p. 96).

The investigation of the Volcano Valley started with the examination of the Jom-Bolok by Egor Pesterev. He was a Russian land surveyor, who worked in the Irkutsk governorate from 1772 to 1781. His report of 1793 says, “The Zhun-Gulak River heads in high stony mountains, but at the very summit of those mountains there is a ravine looking like a valley, and that valley has no great forests or grass. Only black stone, looking like pig iron, stretches in an eight-verst-wide (TN: approx. 8.5 km) band. If a pedestrian has to walk along the stony ravine, he will have his boots torn up when coming to the opposite side because of the sharpness of that black stone, and if a piece of that stone sticks to a horse’s foot, the horse will immediately become lame” (cited from Obruchev, 1973, p. 96).

Several decades later, in 1852, the famous English architect, artist, and travel writer Thomas Witlam Atkinson (1799–1861) visited the Volcano Valley. In 1858, he gave his impression of the beauty of the Sayan Mountains in his magnificently illustrated book “Oriental and Western Siberia,” dedicated to Alexander II of Russia. When Atkinson found lava flows in the Oka valley, he wished to see the region of their effusion. For this purpose, he arranged a small expedition to the valley with an officer of the Oka guard. On the fifth day of the expedition, T.W. Atkinson and his escort of Cossacks, having overcome countless dangers and severities, came to the upper reaches of the Khi-Gol valley and approached the volcanos. Atkinson ascended one of them and described the sight bursting upon his view as a fantastic, amazing scenery of a wonderful highland. He made several sketches, described some parameters of the volcanos, and returned to the Oka valley.

Seeking Siberian Niagara

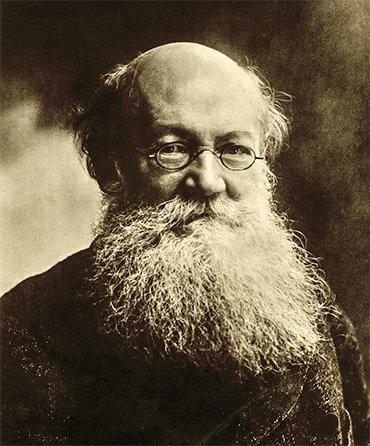

Thirteen years later, in 1865, Prince P.A. Kropotkin visited the Volcano Valley. The main goal of his expedition was to check the statement of the existence of the world’s largest waterfall, over 100 sazhens (TN: about 213 m) in height, in the area controlled by the Oka Guard. This information had been reported in Severnaya Pchela, a St. Petersburg newspaper. It attracted the attention of members of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Geographical Society. Starting from Irkutsk, P.A. Kropotkin made a long journey across the Tunka Depression and Oka upland. He studied various geologic sections and places of interest. Having reached the Oka Guard, located on a high terrace of the Oka River, Kropotkin spent a few days looking for the mysterious waterfall. He found out that the newspaper information was not true. Although there were waterfalls answering the description published in Severnaya Pchela, the largest of them was smaller by an order of magnitude. Kropotkin wrote an article about his expedition to the Oka Guard, which contained the following remark, “I will emphasize for those who hope to find Niagaras on the Oka that, first, I deduce from the perfect match of the description made by the reporter with what I saw that all those waterfallets were the Niagaras he described with the exception that the unknown reporter erroneously indicated the height of 100 sazhens instead of 10 sazhens” (Kropotkin, 1867, p. 62). After the accomplishment of the main task of the expedition, Kropotkin planned to visit the Volcano Valley, because “the tales of the Dzhun-Bulak Valley, the ‘bowl’, and Lake Khar were much more interesting for me than the waterfalls. Thus, two days later I hired horses and went up the Dzhun-Bulak River.” (ibid., p. 63). In moving up the Jom-Bolok Valley, Kropotkin made interesting geological and geomorphological observations, trying to reconstruct the formation of the scenery by invoking geologic data obtained in Europe. In particular, “At the Dzhun-Bulak’s turn northwest, I saw a wild narrow gorge; its bottom was covered with lava, as below, but the valley became much narrower. On the sides, yellowish and greenish limestones formed upright walls. Lumps that had fallen from their edges covered the lava. Huge boulders of yellowish granite with large crystals of black mica were scattered amid them. Their sizes varied broadly. Of special notice was a parallelepipedal block 5.2 m long, 3 m high, and about 2 m thick. Few examples of the transport of such large boulders by water are known. It was reported by Lyell that during the flood in New Hampshire in 1826 water transported boulders of the size of an ordinary room. In 1818, in Banya, water moved enormous boulders as big as a house by quarter mile. The enormity of those boulders and the absence of similar granites from both the right and left banks suggest that these giants could not have fallen from neighboring mountains. It is more likely that they were brought down from the valley peaks by ice. The question could be solved if scars could be observed on the rocks, but I was not able to answer it, because I could not see them clearly at a distance, and it is hardly possible to climb these walls – one should approach them from a different direction” (ibid., pp. 63–64).

The march up the Jom-Bolok crossed harsh and wild areas. “I had been in the very wild taiga but nowhere had I seen anything similar to the Dzhun-Bulak: a narrow gorge; steep, almost upright degrading mountains covered by snow, which descends to valleys in furrows; boulders of several cubic sazhens torn from those steep rugose walls lie on dozens of similar boulders; stunted larches grow from their crevices. They also root in fissures of chapped spongy lavas, utilizing negligible amounts of nascent soil. Lava incrustations, crevices and fissures; sheets of lava crust solidifying at the top, risen from downwards and torn apart; boulders, whose sharp edges cut hooves of barefoot horses… all these, taken together, look as an extremely wild and stern landscape” (ibid., pp. 64–65). After reaching the mouth of the Khi-Gol (alias Khikushka) valley, the explorers left the Jom-Bolok valley and went toward the volcanos. “Concerning the Khikushka valley, it is little different from the Dzhun-Bulak valley with the exception that the vegetation becomes increasingly monotonous. The lava is quite smooth in places, and it would form a satisfactory pavement, had it not been blanketed with cinder. Soon we saw at the valley bottom a dark crater shaped as a regular truncated cone, with a large larch forest on the northeastern slope and moss and snows on other slopes” (ibid., pp. 65–66). Having taken the measurements of the volcano parameters, Kropotkin and his guard took another way back, along the Kadyr-Os River valley and then along the Sentsa River.

The march up the Jom-Bolok crossed harsh and wild areas. “I had been in the very wild taiga but nowhere had I seen anything similar to the Dzhun-Bulak: a narrow gorge; steep, almost upright degrading mountains covered by snow, which descends to valleys in furrows; boulders of several cubic sazhens torn from those steep rugose walls lie on dozens of similar boulders; stunted larches grow from their crevices. They also root in fissures of chapped spongy lavas, utilizing negligible amounts of nascent soil. Lava incrustations, crevices and fissures; sheets of lava crust solidifying at the top, risen from downwards and torn apart; boulders, whose sharp edges cut hooves of barefoot horses… all these, taken together, look as an extremely wild and stern landscape” (ibid., pp. 64–65). After reaching the mouth of the Khi-Gol (alias Khikushka) valley, the explorers left the Jom-Bolok valley and went toward the volcanos. “Concerning the Khikushka valley, it is little different from the Dzhun-Bulak valley with the exception that the vegetation becomes increasingly monotonous. The lava is quite smooth in places, and it would form a satisfactory pavement, had it not been blanketed with cinder. Soon we saw at the valley bottom a dark crater shaped as a regular truncated cone, with a large larch forest on the northeastern slope and moss and snows on other slopes” (ibid., pp. 65–66). Having taken the measurements of the volcano parameters, Kropotkin and his guard took another way back, along the Kadyr-Os River valley and then along the Sentsa River.

The enigmatic death of S. Peretolchin

The next step in the exploration of the Volcano Valley is associated with S. P. Peretolchin. He arranged expeditions to the inner Sayan region in 1912 and 1914. As nobody had studied the volcanos since Kropotkin’s expedition, it was planned to examine the lava field and volcanos in more detail, describe them, and take photographs. The expedition of 1912 failed to reach its goal because of a rainy summer. Peretolchin and the veterinary physician Zakhanovich rose up the Jom-Bolok valley but had to return, as they could not cross the lava field. The expedition of 1914 was disastrous. Peretolchin died in unclear circumstances. His wife Varvara got to the Oka guard with her husband but then she could not follow him, because the back of her horse was raw. Peretolchin was accompanied by Efim Bezotchestva, a Cossack from the village of Shimki in the Tunka Valley, and the observer of the Oka weather station S.M. Tolstoi. The team separated in crossing the Jom-Bolok valley at the Khi-Gol mouth, and this fact was the major premise of Peretolchin’s death. First Tolstoi and then Efim Bezotchestva returned to the Oka Guard by different ways, both thinking that Peretolchin was with the other. Meanwhile, Peretolchin walked to the lower volcano with luggage and equipment and prepared a tripod for taking shots. It was there that something fatal happened. The Oka guard were worried when they did not hear from Peretolchin, and they apprehended his death. A search party, including Varvara, went to the volcano region. The party discovered Peretolchin’s traces a few kilometers from the lower volcano. For an unknown reason, however, the area of further search was shifted from the volcanos to valleys and extended to the distance of 150 km away from the volcanos. The search was resumed several times, until the emergence of the snow cover, but Peretolchin was not found.

The next step in the exploration of the Volcano Valley is associated with S. P. Peretolchin. He arranged expeditions to the inner Sayan region in 1912 and 1914. As nobody had studied the volcanos since Kropotkin’s expedition, it was planned to examine the lava field and volcanos in more detail, describe them, and take photographs. The expedition of 1912 failed to reach its goal because of a rainy summer. Peretolchin and the veterinary physician Zakhanovich rose up the Jom-Bolok valley but had to return, as they could not cross the lava field. The expedition of 1914 was disastrous. Peretolchin died in unclear circumstances. His wife Varvara got to the Oka guard with her husband but then she could not follow him, because the back of her horse was raw. Peretolchin was accompanied by Efim Bezotchestva, a Cossack from the village of Shimki in the Tunka Valley, and the observer of the Oka weather station S.M. Tolstoi. The team separated in crossing the Jom-Bolok valley at the Khi-Gol mouth, and this fact was the major premise of Peretolchin’s death. First Tolstoi and then Efim Bezotchestva returned to the Oka Guard by different ways, both thinking that Peretolchin was with the other. Meanwhile, Peretolchin walked to the lower volcano with luggage and equipment and prepared a tripod for taking shots. It was there that something fatal happened. The Oka guard were worried when they did not hear from Peretolchin, and they apprehended his death. A search party, including Varvara, went to the volcano region. The party discovered Peretolchin’s traces a few kilometers from the lower volcano. For an unknown reason, however, the area of further search was shifted from the volcanos to valleys and extended to the distance of 150 km away from the volcanos. The search was resumed several times, until the emergence of the snow cover, but Peretolchin was not found.

The following year, the search continued. On June 14, Peretolchin’s remains were found in the basalt field 1.5 versts from the volcano and 437 m from a path. Later, Varvara erected a stele at the site of the death of her beloved husband. The inquiry failed to elucidate the cause of his death. Three cases were considered: natural death from a heart attack, attack of a savage beast, and murder by one of the team. Sergei Obruchev analyzed these cases in his book Mysterious Stories (1973) and supported the case of the natural death from a heart attack caused by overwork. In contrast, Varvara Peretolchina accused the observer of the Oka weather station S.M. Tolstoi, who accompanied Peretolchin at that time. Later, the Geographical Society accepted Obruchev’s proposal and named the volcano after Peretopchin. Another, younger volcano was named after the geographer, revolutionist, and anarchism theorist Prince P.A. Kropotkin.

New guides and old paths

The main results of the early studies were the discovery of recent volcanism in Sayan and tentative assessments of the volcano parameters and eruption time. Later, scientists repeatedly investigated the Jom-Bolok lava field with lava effusion sites in the Khi-Gol valley (Obruchev and Lur’e, 1954; Adamovich et al., 1959; Grosvald, 1965; Kiselev et al., 1979; Shchetnikov and Skovitina, 2001; Yarmolyuk et al., 2003). They suggested several volcanic activity steps, polychronism of volcanic bodies, and the tunnel mechanism of the formation of such a long Jom-Bolok lava field. Many explorers noted that the ages of the volcanos and the flow were postglacial, because the basalts either leaned against glacial deposits and landforms or flowed on them. However, the basalts flows cannot be dated directly by the K-Ar or 40Ar/39Ar methods because of their young age and low potassium contents.

The main results of the early studies were the discovery of recent volcanism in Sayan and tentative assessments of the volcano parameters and eruption time. Later, scientists repeatedly investigated the Jom-Bolok lava field with lava effusion sites in the Khi-Gol valley (Obruchev and Lur’e, 1954; Adamovich et al., 1959; Grosvald, 1965; Kiselev et al., 1979; Shchetnikov and Skovitina, 2001; Yarmolyuk et al., 2003). They suggested several volcanic activity steps, polychronism of volcanic bodies, and the tunnel mechanism of the formation of such a long Jom-Bolok lava field. Many explorers noted that the ages of the volcanos and the flow were postglacial, because the basalts either leaned against glacial deposits and landforms or flowed on them. However, the basalts flows cannot be dated directly by the K-Ar or 40Ar/39Ar methods because of their young age and low potassium contents.

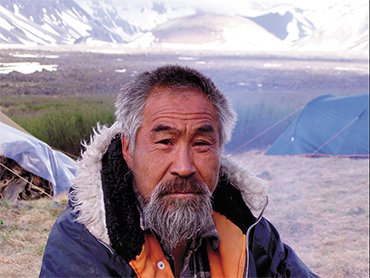

For several years, we continued the studies of our predecessors by attempting to date the volcano eruptions by indirect methods. We obtained the first Be and C dates that could point to the time of the emergence of the Jom-Bolok lava field. All our expeditions were guided by a resident of the village of Sayany Dasha Zhigzhitov. His experience in horse trips and life in mountainous taiga regions was very helpful in overcoming the difficulties of our routes, and we are very grateful to him. The first of our objectives was to date the degradation of the most recent glaciation, after which the Jom-Bolok lava field began its formation. We applied geomorphological methods, remote sensing, and, for the first time in Siberia, 10Be dating of exposed surfaces.

For several years, we continued the studies of our predecessors by attempting to date the volcano eruptions by indirect methods. We obtained the first Be and C dates that could point to the time of the emergence of the Jom-Bolok lava field. All our expeditions were guided by a resident of the village of Sayany Dasha Zhigzhitov. His experience in horse trips and life in mountainous taiga regions was very helpful in overcoming the difficulties of our routes, and we are very grateful to him. The first of our objectives was to date the degradation of the most recent glaciation, after which the Jom-Bolok lava field began its formation. We applied geomorphological methods, remote sensing, and, for the first time in Siberia, 10Be dating of exposed surfaces.

In studying the glacier complexes in the river valleys of the Oka upland (Sentsa, Jom-Bolok, and Sailag), we took and dated 16 samples from the surfaces of boulders resting on moraines and outwash plains. The measurements showed similarly elevated surface concentrations of 10Be in nearly all glacial boulders examined. The sample ages formed two distinct groups: 16.4 ± 0.4 and 22.8 ± 0.6 ka (Arzhannikov et al., 2012). Thus, the age of the exposed surfaces indicates that the lava flow formed no earlier than 16 ka BP, because the valleys were filled with glaciers. Had the eruption occurred during the glaciation, the volcanic rock assemblages and landforms would be similar to tuya volcanos found in Iceland. However, we saw nothing of the sort in the valleys studied.

The evidence of the Atkinson and Peretolchin Volcanos

Our next step was to seek samples for dating directly in the volcano area. First, it was necessary to find thin cinder bodies in the margins of the volcanos that could be penetrated with pits. We assumed that the cinder had buried the day surface, where grass, shrubs, and even trees could have grown, and their remains could be dated by the radiocarbon method. Before long, such a site wasfound. It was a high bank of a creek canyon. The cinders of a volcano rim formed a 2-meter thick layer, black inside and red outside. We named the volcano after Atkinson. The Atkinson and Peretolchin Volcanos are adjacent to each other, and their slopes overlay, which points to their synchronous formation. The pit sections showed that the cinder body consisted of layers differing in cinder particle size. In some cases, breaks between eruptions manifested themselves as horizons of thin pink clayey beds. In cleaning a junction between the cinders, we found well-preserved dark branches of shrub or grass. Apparently, the break between the eruptions lasted for few years, and young vegetation pierced the thin member of cinders of the previous eruptions. Such plant remains were found at the junction between soils and the first cinder horizon (Ivanov et al., 2011). Further search provided information on the conditions of the formation and order of volcano effusions but no more plant remains.

Seeking an ancient pool

After our studies in the upper region were completed, we moved closer to the former Oka Guard, from which in the 19th and early 20th cc. the teams headed by Atkinson, Kropotkin, and Peretolchin started their journeys. The main task concerning that part of the Jom-Bolok area was to assess the area of flooding when the Oka valley was dammed by lavas and to seek datable samples in sediments of the lava-dam lake.

Indeed, the spreading of lavas in the Oka–Jom-Bolok interfluve built a high dam across the Oka riverbed and emergence of a dam lake. Its traces appear in the form of laminated loamy and sandy deposits overlying the basalt flow. While penetrating the loose deposits, we found a carbonic fragment sufficient for radiocarbon dating at a depth of 2 m. On the basis of the radiocarbon dates from the volcano region and from the frontal area of the flow, we concluded that various steps of the Jom-Bolok lava field formation could be characterized. On the other hand, data always seemed insufficient and demanded additional studies. We decided to continue the search for carbon-bearing matter. We investigated a series of loose deposit sections and detected shells of mollusks inhabiting nearshore areas of the dam lake. Simultaneously, we sought and studied sections of deposits underlying the basalts. As the high scarps of the basalt flow, cut by lateral erosion, had been rapidly degraded, the lower areas of their bases were covered with lava fragments. However, there were also complete sections where the underlying deposits, containing gravels, sand clays, and soils, could be clearly read. Lava flew over riverbed surfaces, partially inundated, and calcinated the underlying deposits. Charred vegetation fragments were found in the sections. Subsequent dating by accelerator mass spectrometry showed that the earliest eruptions occurred in the end of the Late Pleistocene, ca. 13 ka BP. There were two major phases, associated with the formation of the Staryi and Peretolchin volcanos. The next eruption occurred in the middle Holocene and formed the Kropotkin Volcano.

In the study of the lowermost reaches of the Jom-Bolok River, we repeatedly noticed spots of very young lavas, thinly covered in lichens, in the matrix of “old” inforestated flows. Their specific features are elongation along the natural dip of the valley and presence of clearly read ripple marks on the basalt flow surface. It looks like the basalt effused from below the surface of old lavas as a single source. Similar young basalts are present in the Khi-Gol valley near the Kropotkin Volcano. Probably, the late volcanic stage was of minor volume, and the effused lava followed lava tunnels and tubes of previous stages. Lava tunnels form in a simple way. Lava cooling produces a thin crust, which traps heat. The lava below the crust remains fluid enough to flow at velocities of tens of kilometers per hour. Cessation of the effusion of new lava portions empties the tunnels, and they remain void for millennia. Probably, the last stage of volcanic activity in Khi-Gol occurred quite recently, slightly earlier than one thousand years ago. It produced young basalt fields. This statement is supported by the age of both living and dead trees on the “islands” of old flows surrounded by nearly modern lavas.

To sum up, we emphasize that the periodic history and times of lava effusion point to long-term volcanic processes inside the Sayan Range. The several stages of effusion indicate that new eruptions may occur in the future.

References

Arzhannikov S. G., Braucher R., Jolivet M., et al. History of late Pleistocene glaciations in the central Sayan-Tuva Upland (Southern Siberia) // Quaternary Sci. Rev. 2012. V. 49. P. 16—32. DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.06.005.

Ivanov A. V., Arzhannikov S. G., Demonterova E. I., et al. Jom-Bolok Holocene volcanic field in the East Sayan Mts., Siberia, Russia: structure, style of eruptions, magma compositions, and radiocarbon dating // Bul. of Volcanology. 2011. V. 73. P. 1279—1294. DOI: 10.1007/s00445-011-0485-9.

Adamovich A. F., Grosval’d M. G., Zonenshajn L. P. Novye dannye o vulkanah Kropotkina i Peretolchina: Materialy po regional’noj geologii. 1959. Vyp. 5. S. 79—90.

Grosval’d M. G. Razvitie rel’efa Sajano-Tuvinskogo nagor’ja. M.: Nauka, 1965. 167 s.

Kiselev A. I., Medvedev M. E., Golovko G. A. Vulkanizm Bajkal’skoj riftovoj zony i problemy glubinnogo magmoobrazovanija. M., 1979.

Kropotkin P. A. Poezdka v Okinskij karaul // Nauchnoe nasledstvo. Petr Alekseevich Kropotkin. Estestvennonauchnye raboty. T. 25. M.: «Nauka», 1998. 270 s.

Obruchev S. V., Lur’e M. L. Vulkany Kropotkina i Peretolchina v Vostochnom Sajane // Trudy laboratorii vulkanologii. Vyp. 8. M.: Izd-vo AN SSSR. 1954.

Obruchev S. V. Tainstvennye istorii. M.: Mysl’, 1973. 57 s.

Shhetnikov A. A., Skovitina T. M. Lavovye reki i vulkany Zhom-Boloka // Zhivopisnaja Rossija. 2001. № 4. S. 43—46.

Jarmoljuk V. V., Nikiforov A. V., Ivanov V. G. Stroenie, sostav, istochniki i mehanizm dolinnyh izlijanij lavovyh potokov Zhom-Bolok (golocen, Juzhno-Bajkal’skaja vulkanicheskaja oblast’) // Vulkanologija i sejsmologija. 2003. № 5. S. 41—59.

The studies were supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, projects Siberia 12-05-98029 and 13-05-00361

The photos used in the article were made by the authors