Treatise of Folk Medicine by Georg W. Steller

A list of common folk remedies collected from 1737 to 1738, both ordinary and sophisticated, taken by mouth or applied externally by Russians, Tatars, Ostyaks, and Chulim Tatars as cures for various diseases, as well as many treatments

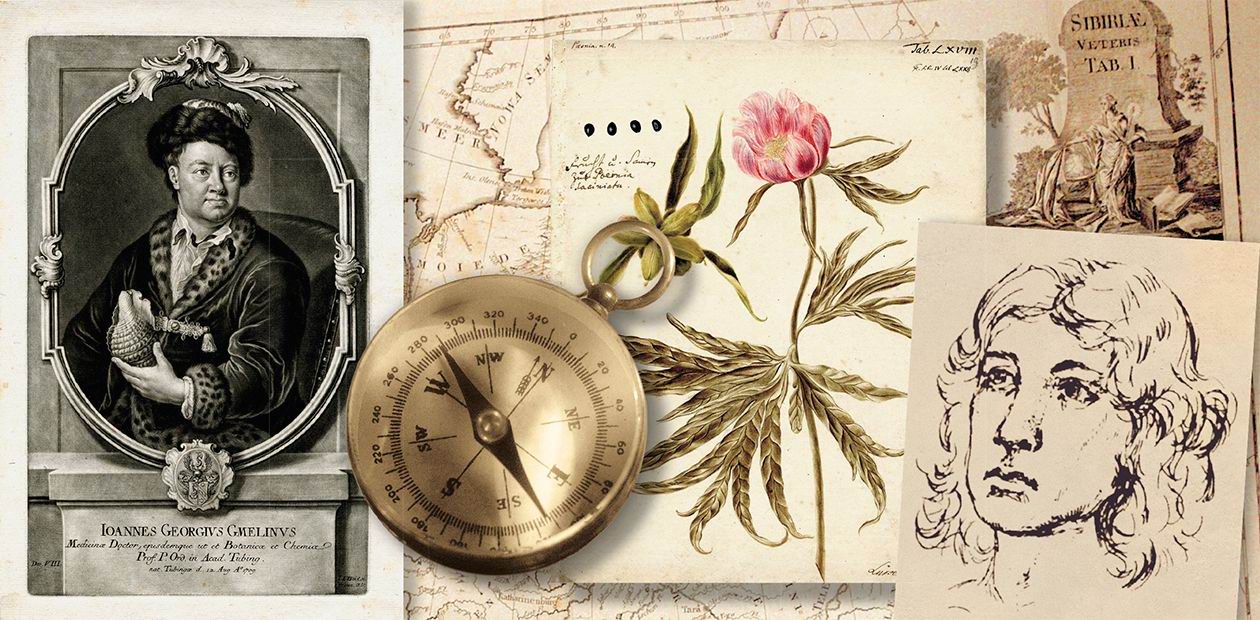

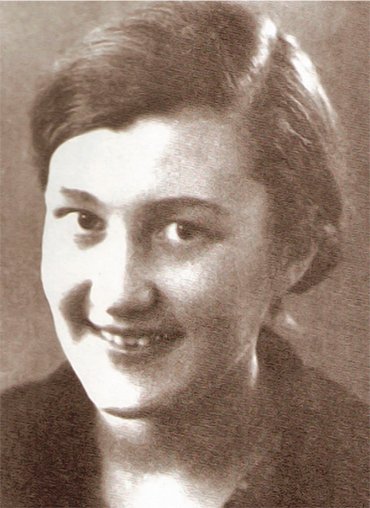

The year 2009 is the tercentenary of birth of Georg Wilhelm Steller and Johann Georg Gmelin, who took part in the Second Kamchatka Expedition, the grandiose research project of the 18th century. They were called to study Siberian nature and to draw the animals and plants. The studies were planned to be done not only in the field: scholars were supposed to make natural collections and dispatch them to the academic museum in St Petersburg for further examination. The things and phenomena that could not be sent had to be impressed as "unknown" natural objects - these were drawn on the spot, and the drawings were sent off to the Academy of Sciences. Many of these observations, studies and drawings have been published but a lot of no less important and exciting things are waiting in the archives. Steller's treatise on folk medicine translated from Latin by the well-known historian of science Tatiana A. Lukina is an early work on the Russian Far North and Far East ethnography. It is of great value as it gives an idea of the rational knowledge of the flora possessed by the Siberian peoples in those distant times; the treatise familiarizes us with the ways and methods of treatment with medicinal herbs used both by indigenous people of Siberia and "immigrants". To this day, many of the plants mentioned in his treatise have been widely applied in folk and official medicine. The treatise deals in detail with some prejudices and magical cures, exotic traditions of Siberian aboriginals. The unique drawings from the St. Petersburg Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences Archive are used in this article

Anniversaries in the history of science give us the opportunity to look back and remember our distant forerunners. The year 2009 is the tercentenary of birth of Georg Wilhelm Steller and Johann Georg Gmelin, who took part in the Second Kamchatka Expedition. When scholars write about this grandiose research project of the 18th century, they justly treat with great respect and pay homage to the contribution made by every member of the “academic detachment” to the complex study of Siberia.

Gmelin and Steller’s contemporary was another member of the expedition, the drawer Johann-Christian Berckhan. The year they set off on the expedition from St Petersburg they all were under 25. The three were related professionally: Gmelin and Steller were called to study Siberian nature and Berckhan was brought to draw the animals and plants. The studies were planned to be done not only in the field: scholars were supposed to make natural collections and dispatch them to the academic museum in St Petersburg for further examination. The things and phenomena that could not be sent had to be impressed as “unknown” natural objects – these were drawn on the spot, and the drawings were sent off to the Academy of Sciences. The collections gathered by the scholars and the number of drawings stagger imagination. Many of these observations, studies and drawings have been published but a lot of no less important and exciting things are waiting in the archives.

Translator’s introduction

...From the very first days of his journey, on the way from Moscow to Yeniseisk, Steller made notes on the everyday life and ways of the population, drew up lists and descriptions of plants and animals, gathered materials on folk medicine. Upon arrival in Yeniseisk, he dispatched everything to the Academy. One of these manuscripts was the treatise on folk remedies and treatments.

...From the very first days of his journey, on the way from Moscow to Yeniseisk, Steller made notes on the everyday life and ways of the population, drew up lists and descriptions of plants and animals, gathered materials on folk medicine. Upon arrival in Yeniseisk, he dispatched everything to the Academy. One of these manuscripts was the treatise on folk remedies and treatments.

It is not surprising that in Siberia Steller was interested in medicine. For a then doctor and a traveler, this is understandable. In the 18th century, study of medicinal plants came into vogue. Steller collected evidence on wild-growing healing herbs and various treatments for diseases, which he sometimes tested on himself. He described in detail remedies used by the Russians and Ukrainians living in Siberia, as well as, which is especially valuable, those applied by the Nenets, Koriaks, Mansi, Itelmens, Khanty, Udmurts, Mari, Evens, Yukagirs, and Tatars; he did his best to note all the useful and important things found in folk knowledge about nature. To this day, many of the plants mentioned in his treatise have been widely applied in medicine; some of them were known in Russia before the 18th century; however, Steller has undoubtedly discovered a lot of Siberian medicinal plants.

One of the most common and, as a rule, incurable diseases of the time was scurvy. Even sailors of the Bering expedition who had scurvy were not willing to follow Steller’s advice.

Practical knowledge on curing scurvy possessed by the Siberian minorities and recorded by Steller is of interest for comparative history; for example, similar remedies prepared from plants were later used by the Nenets.

The treatise reports healers improving cardiac performance, cures for skin diseases, antihelminitics, and antirheumatic curatives. Steller believed that herb extracts and brewers’ yeast were extremely efficient against carbuncles.

On the other hand, not all ideas of folk medicine about healing properties of a certain plant were true. Some remedies prepared from them were useless, if not dangerous. Steller paid a lot of attention to wrong and harmful treatments practiced by local doctors and quacks, who would make children take powdered blue copper, give their patients poisonous hellebore water, which made many people die, and put those having a fever into the cold water of rivers and wells. He also mentioned pseudo-drugs: nonexistent “ant” and “water” oils, baked onion as a cure for toothache, healing properties of dry frogs, and noted the cases when these treatments helped. As a rule, Steller did not dwell on apparent absurdities and ridiculous mistakes made by ignorant charlatans.

The treatise deals in detail with some prejudices and magical cures. For instance, according to Steller’s observations, buttercup and hellebore extracts were used to ward off evil spirits or the evil eye (the latter was a Russian belief); and horse’s hoof meat was a common amulet. He also mentioned comic practices such as getting stupefied with hog bean in a steam bath, treat guests with arrow-wood water looking like plain water but causing intoxication. In the end of his treatise the author reports a practice the Khanty and other Siberian minorities had of intoxicating themselves by eating poisonous mushrooms.

Steller’s treatise translated from Latin and published below is an early work on the Russian Far North and Far East ethnography. It is of great value as it gives an idea of the rational knowledge of the flora possessed by the Siberian peoples in those distant times; the treatise familiarizes us with the ways and methods of treatment with medicinal herbs.

Tatiana A. Lukina (1917-1999)

In Moscow and in all the villages round about they put in a pot split birch twigs cleared of leaves and an equal proportion of ash-wood chips and distill, by heating, an acrid transparent reddish alcohol, which is applied to embrocate members of a person suffering from scurvy and rheumatic pains (called “bone twist”), as well as from hernia. The Tatars take almost the same alcohol, from forty to a hundred drops, during several days. As it became known later, the Vyborg Finns are familiar with this sort of alcohol too.

Down to Nizhny Novgorod they use Xylosteum tree to prepare through distillation vitriol oil – black, heavy, and with a strong smell. It is applied externally to treat uninflamed tumors, mostly with a good result. It is taken in to for the French disease (syphilis) at any stage, scurvy, and scabies. In all the aforesaid localities they sell it at stores as “honeyberry oil.” It is one of the most tradable Russian medicines.

The red Chinese ointment ten-sui is on sale in Moscow stores. This is a rheumatic remedy of Moscow’s Russian residents, which I have failed to procure so far; it is made in the same way as the genuine, Chinese [ointment] is prepared by Russians living in Siberia. They pour wine alcohol in dough and apply it to inflamed body areas. This medicine is universally lauded.

Muscovites use corydalis (Fumaria bulbosa), grass, and roots to make alcohol by hot fermentation, with the help of brewers’ yeast. In the spring this folk remedy is adhibited instead of wine alcohol to treat scurvy. It is very much advised.

In the vicinity of Moscow and Kasimov, Russians powder radish (Raphanus rusticanus) or horse radish (Armoracia) roots and, by heating, distill the so-called “horse radish oil,” which is taken in and applied externally for scurvy-invoked rheumatisms, and is said to be very helpful.

The main event in the short life of prominent naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller was his journey across the unknown expanse of Siberia and Kamchatka. Back in the 18th century, it took an extraordinary and stout-hearted man to live through many years of travels in the north.

The main event in the short life of prominent naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller was his journey across the unknown expanse of Siberia and Kamchatka. Back in the 18th century, it took an extraordinary and stout-hearted man to live through many years of travels in the north.

Steller was born in Windsheim, a small town in Bavaria, in the family of an organist, in 1709. From his school years, he demonstrated outstanding abilities, industry, and interest in natural sciences. In 1729 he became a student of the Theology Department with the University of Wittenberg, and in 1731 was admitted to the University of Halle, where he studied anatomy and natural sciences, mainly botany.

Having completed his university studies, Steller failed to find a job in Germany. In Danzig the young doctor got the position of a surgeon at the Russian military hospital. As he accompanied wounded soldiers to Kronstadt, he pursued his long dream to visit Russia’s capital. Steller was among the founders of Botanical Gardens of St Petersburg Academy of Sciences. He applied to the Academy president with a request to join the Kamchatka expedition and was accepted.

In this way Steller became a participant of the second stage of the Great Northern Expedition designed by Peter the Great and carried out in 1725—1743. The first detachment of the Second Kamchatka expedition rounded the Arctic shore; the second detachment sailed from Kamchatka to America; Steller was a member of the third, academic, detachment. The Senate’s decree on dispatching Steller on the Kamchatka expedition was signed in August 1737; in December, the scientist set off on his long journey to Kamchatka, accompanied by drawer J. Ch. Berckhan.

The traveler went to the Urals through Kazan, made a stop in Tobolsk, went down the River Irtysh to the Ob and then up the Ob to Tomsk. In December 1738 he reached Yeniseysk. His further travel route took him to Irkutsk. He surveyed Lake Baikal shore, and explored the flora and fauna of the Barguzin Range. For eight months Steller investigated Kamchatka, and then accepted V. Bering’s offer to join his voyage to America.

During the voyage with Bering, Steller made many ethnographic observations and discovered new plant species, especially medicinal. In October 1741 the ship was wrecked. During the involuntary wintering on an island Steller hiked across it and took notes. He made collections, dissected animals, and – most importantly – described the rare animal of the sea-cow gender, Steller’s sea cow (Phytina stelleri), soon to become extinct.

The survivors of the Bering crew built a boat from the wreckage and set sail in August 1742. Having gone ashore in Avachinsk Bay, Steller went on foot from Petropavlovsk to Bolsheretsk. There, he had been given up for lost and the news was conveyed to Petersburg. All his assets had been sold.

In March 1745 the explorer received the order from the Academy to return to Petersburg. On the way to Tobolsk Steller felt unwell but paid no attention and continued his travel. In November 1746 he died in Tyumen; he was 37 years old.

Steller managed to process only a small part of the materials he collected. Among his numerous works, mostly left in the form of manuscripts, of greater interest for Siberian ethnography are Description of all things seen and observed during the sea voyage and History of Kamchatka, written in 1742—1743. Both manuscripts were used by S. P. Krasheninnikov in his printed work published prior to these manuscripts. Siberian Flora by J. H. Gmelin abounds in reference to Steller’s unpublished works, especially to his Irkutsk Flora that includes notes on 1100 plants

Hellebore (Veratrum, or Elleborum album) roots are praised universally by Russians both in Russia and Siberia. They swallow bits of uncooked roots, sometimes add them to the Russian drink prepared through fermentation (called kvas), or cook them for a long time in the bread oven after bread has been taken out, and thoughtlessly run risks when they offer this potion to the sick. As a result, there have been about 60 victims from Moscow to Tobolsk, as I noted in my diary. Some of them died, others came down with incurable diseases with serious symptoms. Because of this strong remedy, a few women of easy virtue had miscarriages. Taking this medicine has made some of them hysterical and provoked a few cases of tuberculosis; some of these women died young; there were several whose legs grew numb. This deadly plant is usually harvested in April. They put it in a pot and wait for the leaves to fade and grow yellow. Then the root is said to become stronger and more effective. No other remedy in Russia and Siberia has killed and crippled so many people as this one, though Russians can take very strong medications without any harm.

As a cure for a three-day fever, Siberian villagers wear an amulet. It is made of meat cut out of a horse hoof. I learnt about this funny remedy from a military man who had applied it in vain before he turned to me for help.

Russians living on the Volga prepare alcohol by fermentation from brier flowers. It is used to improve cardiac activity and is called “brier vodka.” Having cut and cooked brier roots, Russians in Yakutsk drink this potion with the same aim. It is used instead of Chinese tea, it cheers a person up.

Severe scurvy (Scharbock), which tortures the Volga residents, children, boys and girls, spreads like a plague. It starts on the face and mucus membrane. On the fingers, stomach and legs evil-smelling ulcers appear that discharge yellow pus; the lips redden and harden, the limbs become crooked and disfigured because of terrible tumors: it takes the disease three to four years to depress the whole body completely. As far as I managed to learn from communication with the people involved and personal observation of the symptoms, the disease was cured by broad and frequent transections of the veins, prolonged ingestion of tarry decoctions, and in some cases by taking pine and fir wood decoctions. Also, I observed that some people took turpentine oil.

Peasants on the Volga and in Siberia treat broken bones with linden bark, or lime bast. The bark is put on sticks so that the bandage does not contact the shoulder or the shin. In order to avoid tumors and ulcers, bread alcohol is poured on the bandage, and the limb is wrapped in linden bark. In thirteen days the patients are given powdered dust obtained from scratching copper, which, in the peasants’ opinion, accelerates the bone union.

Onion, baked in cinder and then sliced, is applied to the cheek, against the spot where one feels toothache, and is held as long as one can endure the heat. Those who have undergone this treatment state that it helps immediately.

In Russia and Siberia, Russians burn Henbane (Hyoscyamus), together with roots, leaves, and flowers, in steam bath stoves out of mere play or for some other reasons. Those washing in the baths temporarily become delirious or perform amusing absurdities for a few hours. The Russians call this plant belena.

The Siberians are good at making all kinds of abscesses come to a head and erupt quickly and safely. To achieve this, a dressing soaked in brewers’ yeast is applied. I think this remedy should not be ignored as it is not devoid of sense. The flour particles surrounding the yeast block the pores and thus impede evaporation. This improves the blood quality and aids blood circulation.

In 1736 Siberians in Tobolsk suffered from carbuncle epidemics. First this pestilence besieged horses, cows, calves, and then spread to people of both sexes and any age. All of a sudden, red spots that burned insupportably appeared under the chin, in the armpits, or on the thighs. In a few hours, the tumor increased considerably, which was accompanied by a high body temperature. A fever with profuse perspiration and headache developed, the eyes grew red.

An old peasant, a medicine man, having collected a lot of different herbs and processed them in the way described below, nursed many people back to health very quickly and successfully. He picked up and dried crushed cornflower (Jacea vulgaris) or centaury (Centaurium) with red flowers, mixed them with brewers’ yeast to obtain a tender mash, which he slightly heated and applied to the carbuncle. The sick person was put to bed and given milk, fish oil, bread alcohol, and decoction made from the same herb together with its flowers; he or she was carefully looked after. Finally, one night the carbuncle erupted, and all the symptoms of the disease weakened. The wound was powdered with ammonium salt.

Johann Georg Gmelin was born in the German town of Tubingen, in the family of a well-known pharmacist, who taught his son chemistry and pharmacy. Gmelin arrived in St Petersburg when he was 18 years old (as a matter of fact, almost all first Petersburg professors were young). The able young man was appointed to Kunstkamera, first as a volunteer; in a year he was engaged by the Academy of Sciences and offered a small emolument.

Johann Georg Gmelin was born in the German town of Tubingen, in the family of a well-known pharmacist, who taught his son chemistry and pharmacy. Gmelin arrived in St Petersburg when he was 18 years old (as a matter of fact, almost all first Petersburg professors were young). The able young man was appointed to Kunstkamera, first as a volunteer; in a year he was engaged by the Academy of Sciences and offered a small emolument.

Gmelin was involved not only in sorting out and describing collections but also in doing research – the results were later published in the Academy’s scientific journal. For his scientific achievements, the young scientist was appointed Extraordinary Academician in 1730 and offered 400 rubles remuneration in contrast to the 120 rubles paid previously; the next year he was appointed professor of chemistry and natural history. The reputation of the 27-year old scientist was so high that President of the Academy of Sciences L. L. Blumentrost charged him to make a speech at the public meeting on the occasion of Empress Anna Ioannovna’s name day, which he devoted to “the origin and success of chemistry.”

In August 1732 Gmelin was made a member of the Second Kamchatka expedition. He was commissioned with preparation of instructions for natural history researchers. Before the departure, Gmelin deposited ten manuscripts in the archives, which included a brief course in natural history read to students setting out on the expedition and a catalogue of minerals kept at Kunstkamera.

In August of the following year, members of the expedition departed from Petersburg. Upon his return from the expedition, in February 1746, Gmelin delivered the first volume of his work Flora Sibirica (published in 1747) and filed a request for a year’s leave to his motherland, his native Tubingen. When his leave was over, Gmelin lingered in going back, and then informed that he was not going to return to St Petersburg at all. His warrantors, M. V. Lomonosov and G. F. Mueller, were ordered to compensate half of his remuneration; however, the decision was later cancelled, and only the warranty amount was held back.

In the meanwhile, S. P. Krasheninnikov, who became the first Russian professor of natural history and botany at the Academy of Sciences, prepared for publication the second volume of Gmelin’s Flora Sibirica and issued, separately, the Russian translation of the author’s preface to the first volume.

In March 1750, the Academy of Sciences requested from Gmelin the manuscript of Flora Sibirica’s continuance, promising a 200 ruble fee per volume. The Academy was ready to forgive him for not returning to Petersburg in exchange for the manuscript.

In 1751—1752 Gmelin published in Gottingen the notes of his journey across Siberia Johann Georg Gmelins Reise durch Sibirien von dem Jahr 1733—1743; after the book came out, the Academy’s Chancellery charged Lomonosov to write a review highlighting which of the evidence it contained was “memorable and useful” and which was “excessive, indecent, and doubtful.” The last two volumes of Flora Sibirica were published in Petersburg in 1768 and 1769, after Gmelin’s death, by his nephew S. G. Gmelin holding the position of professor of botany with the Petersburg Academy of Sciences.

For some time he guarded the sick not allowing the wife or the children to look at the carbuncle before the matter was discharged. Even though this poison could not do any harm to the sick, the disease could spread easily to the others, as it was the case with one boy. He looked at his father’s carbuncle and in a few hours developed a tumor under the chin, as well as the other symptoms I have described above. The boy was treated with the same internal and external remedies. The tumor gradually disappeared, and, simultaneously with frequent perspiration, the health restored.

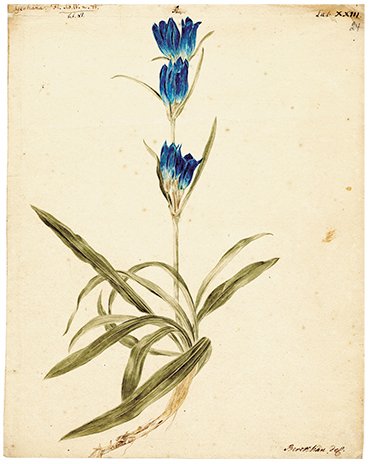

Rumors about the successful treatment reached me when I was in Tobolsk. I heard from many people that they were cured this way. It should be checked whether some gentian roots (Gentiana) were added to the remarkable cornflowers. In this case, the remedy can easily become an antitoxin.

During childbirth, in bad cases, the Mari women are hung over the stove in the centre, in the place heated by the stove from below, and they hold on to a beam. Then the neighbors come, sit around and wait for the baby to come out. The hung woman screams; they do not give any medicine to the women in childbirth and have no midwives.

During childbirth, in bad cases, the Mari women are hung over the stove in the centre, in the place heated by the stove from below, and they hold on to a beam. Then the neighbors come, sit around and wait for the baby to come out. The hung woman screams; they do not give any medicine to the women in childbirth and have no midwives.

For backache, Permiaks on the Kama rub down, in the baths, the ground roots of cicuta. They warn that the very middle of the back cannot be touched not to make the matters worse.

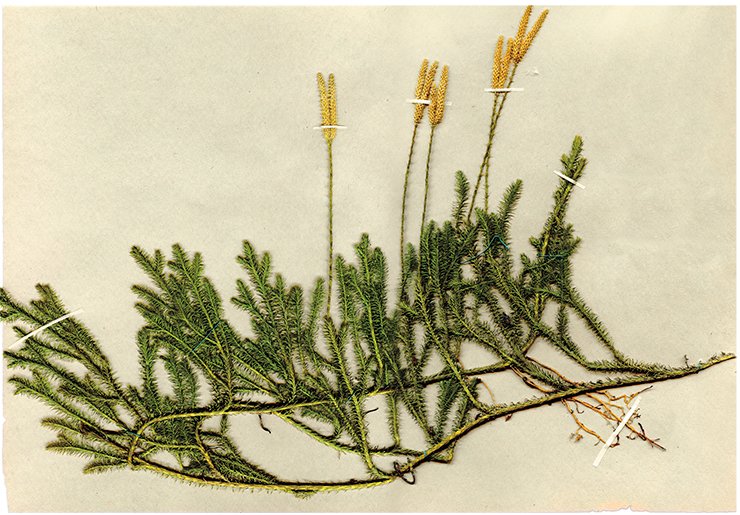

Lycopodium with leaves similar to that of juniper is cooked in the water, and the decoction is taken for: 1) expulsion of fetus, 2) accelerating regular childbirth, 3)treating yellow plague, and 4) treating three-day fever.

The Permiaks and Siberians administer a potion made of Napellus, or Aconitum, to the sick having scabies. After bread is taken out of the oven, they put in a drink called kvas to aid fermentation, and slowly add Napellus to it. It is worth mentioning that many have died from this Acheron ambrosia at once. We can thus see how self-willed medical practitioners in these localities are.

Wolosok (a hair) is the Russian disease that received its name not from a hair in the wound but from a worm looking like a hair, which has got into a non-healing ulcer. This is what the Russian think. This malicious ulcer starts from an inflammation accompanied with oily egesta. Russians normally treat it with butter, pork fat, and “teget” ointment. This disease occurred in ancient times. Nowadays, the more clearly modern doctors can explain the harm caused by reeds, the less often peasants suffer from this disease. Nevertheless, it has driven to grave many Russians and Siberians. I saw those who managed to recover, they cured themselves with white arsenic; I was a witness to it.

Russian practitioners, together with their German colleagues, believe it is helpful to refer to soapy and slimy liquids, both man-made and natural, having traces of oils such Oleum Tartari, as “oils.” For instance, Russian natural Aesculapians would bring to me and ask to examine three “oils,” very common in Russia and Siberia.

The first is called “ant oil” (Oleum formicarum). This natural oil is on sale as a cure-all. I made an effort to take part in this panacea – actually, to find it myself. The general opinion is as follows: during John the Baptist holiday you can find a certain yellow matter of golden color inside anthills – it is very smelly and dissolves easily in any liquid. A gulp of this solution is sufficient to return to life a dying man. Gouty persons and rheumatics get rid of the disease for good, both inside and outside, without any trace.

However, the Russians’ conflicting and contradictory messages did not seem trustworthy. I had an impression that they said a lot of things that did not count. The alleged owners of this miracle appeared not to have ever seen or had it. The Siberian fir resin referred to by the Germans as “Mastichis” and by the Russians as “earth or ant incense” is known to be usually collected from anthills. It is highly probable that the Russians subsequently gave it the name above, or they took this matter for the mucous mushroom rudiments, which looks more like the truth.

Buttercup (Ranunculus nemorosus) with white flowers, called “white flower” in Russian, can be applied in different situations.

Firstly, it is used to treat skin sores, put on reddened skin and blisters. Second, in steam baths, the herb crumbled together with its leaves is rubbed in the back for sciatica. Patients say that no other treatment helps better; the skin covered with blisters hurts less than it used to. However, recovery is hindered by the ulcers, noticeably indurated. Acrid, burning watery liquid discharged from the ulcers turns all the back into a very painful sore. This effect should be attributed not to the friction caused by the herb but to the fact that the body of the person taking a steam bath is so sweltered that it becomes red and the person feels exhausted. This is a serious impediment to recovery.

Here are only a few examples: in 1734 ten drawings of new herbs and 216 dried herbs were sent; in 1735 they sent from Irkutsk, among other things, a “drawing of the vessel in which the Tungus carry wine, drawn through the painter Berckhan”; in 1735 the box with plants dispatched from Yamyshev salt lake had, alongside herbs, 33 sheets of drawings; in 1738, 81 sheets with a hundred drawings of new herbs; in 1740, “85 drawings of different herbs that have not been described previously on 72 sheets” from Irkutsk and the rivers Angara River, Tunguska, and Yenisei, and 15 drawings of new herbs by adjunct Steller; drawings of archaeological findings, pictures showing the Yakuts’ rituals and everyday life, and so on.

It goes without saying that had it not been for the work done Berckhan, Lurzenius, and Dekker, the achievements made by the academic detachment of the Second Kamchatka expedition could have been less impressive.

We should remember that some drawings burnt during the fire of 1747. Documents of the St Petersburg Branch of RAS Archives can help us to determine which drawings did not survive – after the fire the Academy of Sciences authorities ordered to make a list of the things burnt. The Archive contains reports submitted by the artists; in his first report Berckhan writes that the “botanical drawings given for making copies and kept in the big box got burnt, and the drawings I brought from Siberia last are all intact.” (The last drawings were “75 herbs, 14 birds, 9 mushrooms, 21 fishes, 4 animals, 5 prospects, 9 birds’ eggs. 26 drawings have not been finished.”)

From another report of the artist we find out that during the fire a box with 237 drawings was saved from the drawing chamber: “93 drawings of herbs including 9 copies, 21 drawings of fishes, 14 drawings of birds, 4 drawings of animals, 9 drawings of mushrooms, 9 drawings of eggs from different birds, 7 shaded prospects, 30 paintings of various Siberian peoples, 27 shaded drawings of the same peoples, 7 drawings of Siberian people’s dress,16 drawings not completed.”

…To his last day, Berckhan performed his duties for the Academy’s Museum. The Academy’s commission that visited the apartment of the deceased following his death discovered “a few sheets, made in China ink, of birds, and one painted animal, and another one, only begun”

Stonecrop (Sedum) with leaves similar to these of rosemary is widely used by Russian Siberians to disinfect their homes of bugs and to scare them off. First of all, the windows and vents are closed tight, then the herb is burned, the oven crown is left open for a day or two. Having come back home, the inhabitants clear the room of dead or stupefied bugs, and for a year are saved from their bites. As the year elapses, it is advised to re-do the fumigation.

Blue copper (Vitriolum Cuprium), powdered and mixed with milk, is given to babies who are only a few months old; Russian Siberians are convinced that the projectile vomiting caused by it will rid the babies of coughing, labored breathing, and excessive afflux of mucus.

Russian Siberians prepare yarrow (Millefolium vulgare) extract on ordinary vodka and then distill it again. They assure that the quantity of alcohol increases, it acquires a pleasant smell, and, on top of that, a beautiful sapphire-blue color. I have not tried doing it but the chemical observations made by the dignified gentleman Hoffman support this assertion. He writes that this herb produces oil of a beautiful blue color. It should hardly be doubted that one can obtain alcohol of the same color from chamomile (Chamomilla) flowers.

The Ukrainians tint vodka in a beautiful blue color by preparing, in the same way, an extract of burnet (Sanguisorba major) roots. The same experiment done in Siberia, however, was not successful; the alcohol did not become blue. The conclusion can be drawn that the Ukrainian burnet is another species, different from the ordinary one growing in Siberia.

Ripe red berries of common snowball (Opulum ruellium) with a plain white flower are used by Russian Siberians for a funny experiment. Ripe fruit is put in a new pot, some sugar is added, alcohol, or, even better, vodka, is poured in, and the pot is covered with a lid and done over with dough to avoid evaporation. The pot is kept in a stove for a long time, until it шы apparent that the berries have become devoid of any color and are snow white, like white wax. Liquid drawn from the berries looks like plain water, it has not smell or taste, but has an intoxicating power; it is harmless. Tea, the Chinese herb, is added to this liquid. The infusion is offered to those who refuse to take alcohol and imbibe; in this way they are made to join the merrymaking. Without realizing it, people unwillingly get drunk.

Anemone, or pasque flower (Pulsatilla), with anemone-like leaves and orange flowers is used by Siberians to treat ulcers and blisters: the plant is crushed and applied to any part of the body for the night. Besides, it is used as a means to provoke, without any fear, a disease in order to avoid military or some other kind of service. Having injured themselves, they take unsalted butter, mix it with yellow wax, and apply it to the sores. If they stay like that for two or even three days, a complete recovery follows.

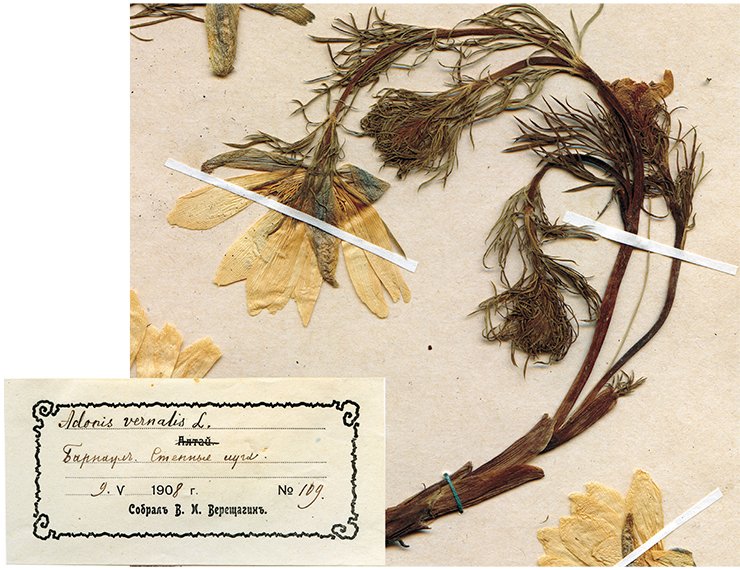

Following the Koran, the Tatars living in the vicinity of Tiumen throw Siberian adonis (Ranunculus foliis ferulaceis) together with the black hellebore (Helleborus niger) roots and camimile (Buphtalmum) flowers on hot coals to ward off the spirit of sickness. They do it both in illness and in good health. Russian Siberians consider Siberian adonis decoction a cure-all: they say it helps for any ailment but best of all for an evil eye.

Fireweed (Chamaenerion speciosum) is called “kipri” by the Russians living on the Lena banks, in Irkutsk and farther on. From this herb, they prepare a drink through fermentation. When the herb is well grown, they gather a large amount of it, take out the stoke piths, add billing water and cook, and then put on a stove not far from the fire to form wort. The beverage produced is sour-sweet and highly praised for its taste; it is drunk instead of the ordinary drink, made from flour.

Caltrop or water chestnut (Tribuloides vulgaris) growing in water is called “rogulik” by the Russians. The Russian population of Tomsk and Chulim Tatars mash its crushed fruit with hot water and take for spasmodic pains and colds, the Tatars call it “arshange.”

Castor (Lac castoris) is used by the Ostiaks [Khanty] to treat babies. It is applied to skin tumors, and the tumor disappears. The Russians living on the Ob banks learnt this from the Ostiaks. They assure that is a good remedy for children’s hernias.

The Chulym Tatars dry river frogs in the open air and in the wind, crush to powder, and sift on sores; for internal injuries and ruptures the frogs are usually cooked and the decoction obtained is taken in.

Russians living in Tomsk have the following treatment for people suffering from high fever: in the summer they are put down in terribly cold wells and in the winter they, completely naked, are put under the ice and kept there as long as possible. After that the patient is taken out, wrapped in a cloth and put to bed. The sick is covered with many blankets, he sweats, and in a few days the fever is gone. Most doctors will probably think that it is a wrong and silly remedy but the facts are that, as a rule, the sick get rid of their disease without any particular loss of strength. Personally, I did not dare to receive this kind of baptism in the river.

Another way to treat high fever common with Tomsk inhabitants is taking the sick to a steam bath, where he should sweat a lot; his body is then rubbed over with very cold pickled cucumbers and put to bed; it has never been doubted that the sick will soon recover.

The only way in which the Khanty can give relief to a wounded relation is to ask the Russian for pigs’ bones. Grated bones are sifted on the wound. I witnessed that they did not admit to anybody a successful outcome of this treatment.

Glossy Black Chokecherry (Cerasus racemosa, or Padus theophrasti) is a source of food and drink for Russians and many Tatar peoples. Russians, especially Tomsk residents, are very good at drying these berries in a stove. Dried berries are offered as a dessert; they are munched together with the stones and swallowed. Fresh chokecherry berries are a favorite dainty with the Russians and with Tatar tribes. This summer even bears, which feed on these berries too, had bloody fights for them from the River Ob to the Chulym. People make chokecherry pies (they bake them in an oven) and sometimes crumble fresh berries, fill a barrel with them to a half, add boiling water, and put in a pantry until all the color goes into the water and the water becomes the color of red wine. This beverage is separated from the berries and offered to guests as a replacement of red wine. It is not easy to distinguish between it and cheap red wines.

Gooseberry without thorns and with big black berries, abounding along the banks of the rivers Irtysh, Ob, and Tom is another substitute for grapes good for Russian Siberians, Tatar tribes, and bears. Three kinds of drinks are made out of it.

The first and the second are prepared in a very similar way with the only difference: to the second one, honey is added so it is of better taste than the first. To the third, vodka is added, or squeezed juice is mixed with vodka. These drinks are used instead of wine during festivities, when making vows; they are taken with reverence.

Mountain cranberries ([Vaccinium] vitis idaea) are processed in the same way. Frosted rowan berries (Sorbus aucuparia) are used as a dessert by the population all over Russia and in Siberia. Tomsk citizens add boiling water to the crushed berries and with the help of bread yeast make the alcohol stronger than bread wine and with quite a nice taste. White wine is, however, preferred because rowan berries are astringent.

Cow parsnip, or hogweed, (Spondylium) is quite common with Russians too. In early spring its tender leaves are cooked, instead of cabbage, with meat. The same is practiced in the Ukraine. The Siberians collect stalks of adult plants separately, cut them, add boiling water, and ferment. Then the cooked stalks are eaten and souse is drunk by peasants.

In some localities in Siberia hogweed is used to prepare large amounts of ordinary alcohol. Hogweed stalks and leves are cut, put in a barrel 4 fingers up (approximately 17 inches), 1 finger of flour is added and the mixture is left to ferment until the barrel becomes full to the brim. After that, the mash is mixed with boiling water and two or three lumps of bread yeast, and in two days it is distilled. If there is no special apparatus, it can be replaced with two pots put one on the other and a cylindrical pipe from the hand cannon barrel.

...Russians living from the Viatka to the Yenisei have adopted from the Cheremis, Votiaks, Kazan Tatars, Voguls (Mansi), Ostiaks (Khanty), and Tomsk Tatars the remedy called “moksu,” the best-known and most ancient drug of all Tatar peoples. Everybody makes moksu from dry sagebrush (Artemisia) leaves, though some people use wild safflower (Jacea), and others mullein (Verbascum). Dry leaves are crushed by hands until the fleshy powder-like particles of the plant have been separated and blown off, and nothing but fluff remains.

This fluff can be easily fixed to sore spots with the help of saliva and is a remedy for any disease; the skin is strongly affected with inflammation. Moksu can be applied up to thirty times. They say that the precursor of soon recovery is moksu ignition provoked by elastic skin movement. Moksu swiftly swishes up, having detached from the skin on its own, and falls down on the ground. However, it is not common practice with these tribes to apply moksu to arteries when there is an injury. Wounds are normally smeared with unsalted butter or fish oil – no other treatment is administered, the dressing should fall off on its own. In their language, it is called “zhabni yadki.”

Having examined the condition of many people wearing this kind of dressing and studied their medical histories, I saw that moksu application is never harmless...I have seen several people who resembled dry trees and could not move their arms or legs. Having contracting once, their nerves were partially destroyed, they failed to restore their previous position. Therefore, the septic ulcers could hardly heal. The places of the body that had suffered many burns turned out to be damaged. In the cases in which I observed recovery, this remedy appeared to have healed the illnesses deriving from sudden brood congestion or constipation. This quick well-tried remedy is good for toothache, ear ailments, eye reddening, spontaneous abscesses, sciatica, and other similar diseases.

The Ostyaks living along the banks of the Irtysh and its tributaries, Samoeds (Nenets), Yukagirs, Lamuts (Evens), Kamchadals (Itelmens), and other pagan tribes, whose main asset is vodka and tobacco, have mushrooms that kill flies, called mukhomors in Russian. They eat them not because these mushrooms are tasty, that is, not for pleasure but to intoxicate themselves hard and to become mad, crazy, and disposed to all sorts of vapors of a disordered mind. I heard about it not only from the Ostyaks but was a witness to it.

Their poverty does not allow them to satisfy their unreasonable desires with vodka, and since they have no possibility to buy it regularly, they have replaced it with the fly-killing mushroom. People of both sexes and any age agree to come together (there may be two, three, four, or more of them) in order to spend a few days in a quasi intoxication state. They behave strangely, jump and sing. To come to this state, they intentionally eat one, two, three, or even four uncooked mukhomors, without any preliminary processing. They eat mushroom caps and stipes together with lumps of earth stuck to them, and wash them down with cold water from the river.

In no more than half hour they begin staggering, trembling, and look drunk or mad. They cannot walk steadily or stand firmly, and fall down on the ground, either inside a yurt or outdoors. Firstly, they, as a rule, become insane, lie on their backs, stretch up their legs, ceaselessly twitch and jitter, and then start laughing or singing indecent songs or foretelling the future. Their faces are happy, they feel completely at ease. They stare at the people around with eyes wide open. They assure that they can see not only gorgeous landscapes, meadows, trees and the like but also most graceful girls, various ornaments and other pleasant things. After that they can hear siren birdsong and excellent performance of musical instruments. It seems to them that their bodies grow fantastically, reaching a sazhen (an old Russian measure of distance, equal to 2.13 meters) in diameter and three or more in height, which makes them very happy. The intoxication lasts about five hours, and they get up unwillingly. They have a funny walk: prance boastfully, looking around at their neighbors. They begin bragging of their wealth, strength, and outstanding properties. This is accompanied with singing and playing the musical instrument called “tumbra” (the Russians refer to it as “gudok” (horn)), which reinforces their voices. As they sing, they look back at the spectators, fantasizing that they are arousing everybody’s admiration. The next night they wander around, yelling loudly in the nearby woods, do not sleep, have prolonged talks, and fall into a stupor. As they regain their senses, they become more amiable. Out of special complaisance, they approached me and treated me, very inopportunely, with this prophet manna. Nonetheless, I did not dare to have this horrible mushroom.

After the intoxication was completely gone, in 24 hours, they would take this phantasmal meal again, for a third or forth time. The Russians who have sampled this mushroom out of curiosity fantasized that they were up in heaven, among angels and saints. Not all the Ostiaks though managed to get away with eating these mushrooms: some remained mad to their end and died soon, others felt so frantic that they injured themselves with knives. They slashed their stomachs and perished as they precipitated in the waves. The aid advised by the more cautious did not help either: during this festive folly it was prohibited to come together with women. They said that otherwise you would remain crazy to your death or die immediately, if their reason did not hold them from this contact. Prior to adopting Christianity, the zealot shamans of these tribes used to take the mushrooms as a sacred meal before they started their rituals. This helped them to deceive their people even more shamelessly. I have had reliable information that the Yukagirs attributed great power to this mushroom; having taken the mushroom, the person has to wash it down with the urine of the other person, the latter should drink the urine of a third person, and so on up to the tenth. The urine is believed to have an intoxicating power as well. I examined the people who were in the state of intoxication and failed to notice heart acceleration or any other symptom of blood activation. This poison must primarily affect the nerves as immediately after the mushroom has been taken the nerves are overwrought; old people begin trembling incessantly and suffer from utter debility, they fall into a vegetable state – it happens when they are 40 or 50.

The article is illustrated with the documents from St Petersburg Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Archive (SPB RASA). The materials used in the article have been prepared by Candidate of Philology N. P. Kopaneva, head of the Publications and Exhibitions Department, RASA St Petersburg Branch, based on T. A. Lukina’s article “G. W. Steller about Siberian Folk Medicine (Unpublished Treatise of the 1740s)” // Countries and peoples of the East (Strany i narody Vostoka). Moscow, 1982. Issue 24. P. 127—148

Herbaria materials used in the publications are from the collection of Siberian Central Botanical Gardens (SCBG), SB RAS (Novosibirsk). The editors thank Candidate of Biology E. A. Koroliuk, Candidate of Biology D. N. Shaulo, and Doctor of Biology A. Yu. Koroliuk for their assistance with choosing illustrations