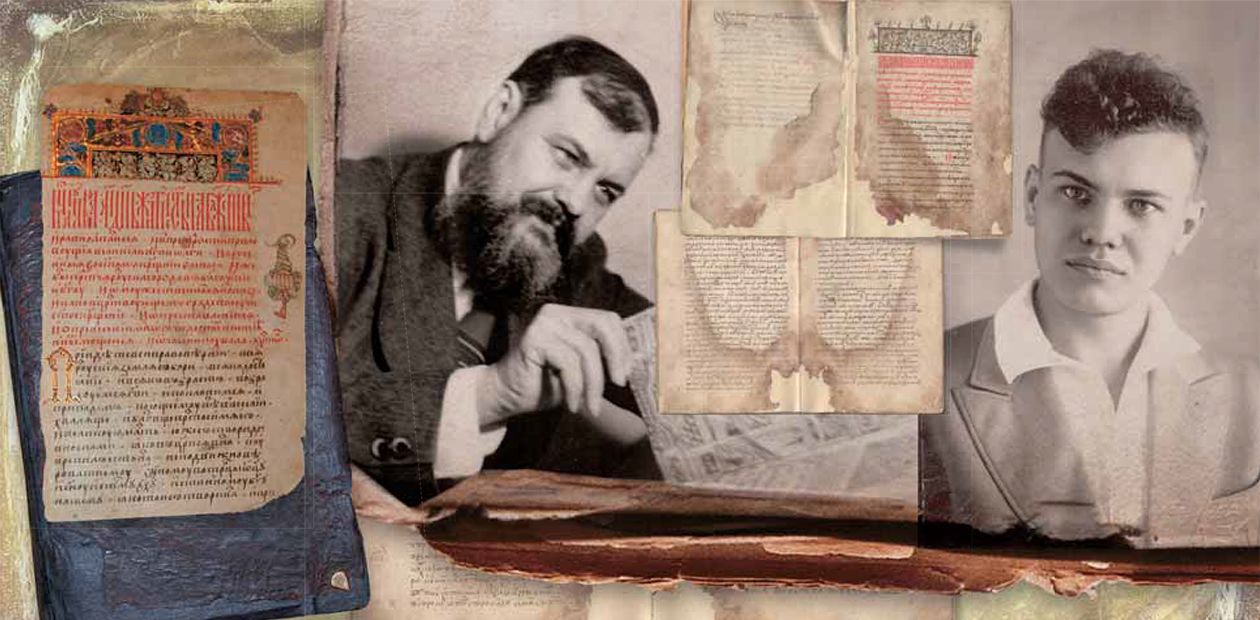

A Quest for Rare Books. To the Anniversary of Academician Nikolai Pokrovsky

In 2010 the eminent historian and authority in archaeography Nikolai Nikolayevich Pokrovsky celebrated his 80th anniversary. He has made plenty of dramatic discoveries in most diverse areas of historical knowledge. His name is associated with the "archaeographic discovery of Siberia": dozens of archaeographic expeditions led by Pokrovsky and his disciples have made it possible to create one of the nation's largest collections of ancient Russian manuscripts and early printed books, bring to light the previously unknown world of the written culture of Old Believer peasants living on the vast territory from the Urals to the Russian Far East.

In his profession, Pokrovsky has always acted as a true archaeographer: he not only sought, described, and published written evidence of the past but conducted thorough source, textological and historical studies.

By the time Soviet historiographers began to write that in the focus of historical investigations should be people, Pokrovsky had for decades enlivened his works with vivid personalities and life stories of the characters he encountered on the pages of ancient manuscripts: peasants, tradesmen, officials, and military governors, whose ideological luggage was an intricate mix of Orthodox Belief and Old Belief, paganism and Christianity.

We offer our readers the hero of the day's story about his exciting "quest for rare books" supplemented with excerpts from his book written based on the materials retrieved during his expeditions and archival investigations

Until the mid-20th century, the Old Russian book culture in Siberia was believed to be represented extremely poorly. Indeed, Russian settlers came to Siberia as late as the 17th century – what kind of old books could be found there?

Nevertheless, the very first expeditions organized by the Archaeographic Commission of the USSR Academy of Sciences in the late 1950s showed that Siberia did have ancient books. Searching for them was not easy though: Old Belief had preserved in Siberia better than in the European part of Russia, hence special attitude to books and mistrust towards aliens.

It was evident that Siberia needed an archaeographic center of its own. Head of the Commission and my teacher Academician M. N. Tikhomirov laid its foundation by donating the invaluable old book collection he had been gathering for many years. This generous gift enabled the university students to learn from the originals the complicated science of identifying, reading, and dating manuscripts.

In early 1965, Tikhomirov and I showed this collection to the Siberian Branch directors Academicians M. A. Lavrentiev and A. L. Yanshin. It was then that the terms of the collection’s transfer to the GPNTB (State Public Research Library of the RAS Siberian Branch), launching archaeographic expeditions and my move to Academgorodok were agreed.

In the summer and fall of 1965, I brought Tikhomirov’s books to Novosibirsk, and the following year my wife Z.V. Borodina and I set off on our first Siberian expedition. Since then, together with our colleagues Ye. K. Romodanovskaya, Ye. I. Dergacheva-Skop, V. N. Alekseyev and followers, we have organized scores of expeditions – from the Nether-Polar Yenisei to the southern borders of Kirgizia and from the Trans-Urals to the Russian Far East.

The first journey

There were problems at every turn. We headed not just for villages inhabited by Old Believers but also for their isolated settlements (sketes). Strangers were not welcome, and communicating was not easy; you stood a good chance not to get a drink of water, and in case you were lucky, the cup from which you had drunk could have been broken as unholy.

Of great assistance was advice of our first-ever archaeographer and founder of the Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkin House)’s book depositary V. I. Malyshev: he told us how to behave with Old Believers, how to approach them, how to ask questions, how to say good-bye and many other things. A strong argument in our favor was our good knowledge of Old Belief history, especially of the 17th century, which the Old Believers themselves did not know very well. We also had a gift highly valuable for them – a big piece of good church incense, which opened many doors. By then, the Old Believers had not had real incense long before and used its adulterations. Later, I discovered a few boxes of incense in an abandoned barn and so our stock was replenished.

Nikolai N. Pokrovsky was born on June 20, 1930 in Rostov-on-Don. His great grandfather was a clergyman and his grandfather headed the legal department of the Northern-Caucasus Railroad Administration. The father, Nikolai Il’ich Pokrovsky, was a well-known historian and the first dean of the History and Arts Department of Rostov State University. His ancestors on the mother’s side, neurologist Tatiana Alekseyevna Prasolova, were Kursk peasants. The grandfather Andrei wandered all over Russia in his search for the spiritual truth, visited Yasnaya Polyana, and finally settled in Rostov-on-Don.The family of remarkable individuals and a rich library containing books in several languages laid down a firm moral foundation that helped Nikolai Pokrovsky endure all the trials of the harsh 20th century and preserve the main feature of his nature – insatiable thirst for knowledge.

Undergraduate and graduate studies at Moscow University and working for the Source Studies Chair acquainted him with the best practices of Moscow historical school. His teachers were such famed scholars as Academicians M. N. Tikhomirov and B. A. Rybakov, Professors N. L. Rubinstein and P. A. Zaionchkovsky.

The young scholar took part in the preparation of the reference book History of the Soviet Society in the Memoirs of Contemporaries. 1917—1957. His name, however, did not show on the book cover: in 1957 Pokrovsky was arrested by KGB for his involvement with an underground group of historians (the well-known “Krasnopevtsev case”) and sentenced to six years’ imprisonment. This was the price the young historian paid for his illusions about the radical character of Khrushchev’s Thaw.

Only in 1963 did Pokrovsky manage to go back to research. For two years he worked at the Vladimir-Suzdal’ Museum, and in 1965 moved to Academgorodok of Novosibirsk, where he engaged at once in a large research project – search for Old Russian books in Siberia.

In his profession, Pokrovsky has always acted as a true archaeographer: he not only sought, described, and published written evidence of the past but conducted thorough source, textological and historical studies.

By the time Soviet historiographers began to write that in the focus of historical investigations should be people, Pokrovsky had for decades enlivened his works with vivid personalities and life stories of the characters he encountered on the pages of ancient manuscripts: peasants, tradesmen, officials, and military governors, whose ideological luggage was an intricate mix of Orthodox Belief and Old Belief, paganism and Christianity

And yet, incense was not enough to talk the Old Believers into giving us the books. These often had to be exchanged, although archaeographers prefer not to expand on it. To this purpose, we set up an exchange stock that contained works of no great interest for scholarly research but important for Old Believers. Frequently, the books were just bought. In villages (not in sketes, of course) they would often fall to people far from belief who were ready to sell them at any price – not like today, when they can ask you an amount ten times higher than the book’s real cost.

What struck me during that first expedition? The Old Believers’ world, their monastic way of life, and most of all, the brilliant book collection discovered in the very first skete. Its owner, Father Palladius, had gathered it for many years. I will never forget him drawing the curtain for show to reveal shelf after shelf jammed with pre-Nikon books, that is publications predating the mid-17th century!

A couple of years after Palladius’ decease, his books were handed out to the people who came to his commemoration, as is the custom with Old Believers. In this way the unique books spread all over the Old Believers’ world. We also got two books – they are now kept at the State Public Research Library in Novosibirsk.

PEASANT WRITERS

We were sitting on a clearing in the woods, near the book copying workshop. It was packed with open manuscripts of all sizes, from the huge Explanatory Psalter weighing over 16 kilograms to the tiny menology. I succeeded in talking the skete’s owner, Father Palladius, to dry his library. The wind lazily rustled the pages, and our talk leisurely wandered from one subject to another. Having looked at the kryuki musical notation, the old man recollected how he learned to sing from it before the Russian-Japanese war. He had even feigned suicide so that his family would not come looking for him and he would have a few years on his own to study.We also talked about how often books have perished and still do: many of the books around us had marks left by a fire or mildew. Father Palladius related me the well-known story by Ivan Peresvetov about the “Turkish sultan Mahmud” trying to burn Greek books. Then we remembered fires made of ancient books in the time of Tsarevna Sofia and czarinas of the 18th c. I asked the old man what he knew about the struggle Old Believer peasants waged in the Urals and Siberia against the Synod members seeking to ruin old books, against inquisitors and missionaries, and for the freedom of their religion. Father Palladius’ reach of thought proved to be far beyond that of the historians’ – he gave us names of the leaders of the 18th-century peasants’ revolt we had never heard of. Where did all that knowledge come from? And then he showed us a book with two copper buckles he himself had lovingly bound. It had stories on the history of the Ural and Siberian Old Believer peasants of the 18th and partly 19th century none of which was known to academics!

(From N. N. Pokrovsky’s book Quest for Rare Books, Ch.2)

As I said, the Old Believers were not strong in their 17th-century history. As for the subsequent centuries, in that very skete we were told about the events and people we had never heard of. And then they showed us a small, deerskin-bound book composed of the previously unknown works by the Ural Old Believer peasants.

Afterwards, we found plenty of such composite books. Primarily it was these finds that allowed Academicians Panchenko and Likhachev to call these expeditions the “archaeographic discovery of Siberia.”

Acquitted 400 years later

Another important achievement of our first expedition was the useful connections we managed to make. Thanks to them, the following year we went to a new region of south-western Siberia, not yet explored by archaeographers.

There we found a book of the 1590s that had once belonged to the local Old Believers. During the purges they were evicted, and the richest book collection was burnt. However, a few books were saved by a local peasant woman. One of the monuments contained in the book and referring to the church reforms of the famous Metropolitan Macarius was published this year in Italy. Of greatest interest though was a copy of the Russian philosopher and theologian Maximus the Greek’s trial record.

He arrived to Moscow from Athos in 1518, when Grand Prince Basili III required a translator of Greek books. Maximus the Greek quickly learned Russian and began translating theological texts but, being and active and passionate person, happened to get involved in the intricate intrigues of the Moscow Kremlin. He was accused of spying for Turkey, plotting against the sovereign’s health, heresy, and so on – in a word, the set that has little changed until the 20th c. The court hearing itself was well known, but the story broke off at what we call today the conclusion to indict. How Maximus the Greek defended himself and what arguments he put forward the historians did not know. Now at last we have the full text of the court hearing and a number of other documents connected with the trial.

All the evidence discovered unambiguously argues for the noted theologian. They had been going to saint him for a long time but the two sentences prohibiting him to take communion from which he had not been exonerated were in the way. Thanks to our find Maximus the Greek was judged not guilty – 400 years after the trial. In 1988, he was sainted at the Russian Orthodox Church Council convened to commemorate the millennium of the Conversion of Russia.

What we do in expeditions is called field archaeography. However, our efforts are not limited to book search. Our formula is: retrieval, study, and publication. The latter requires thorough preparation. We have to work for a long time in the archives of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, most of which had been moved to Moscow and St Petersburg, in order to clarify the lives of the people mentioned in the book.

MAXIMUS THE GREEK

At the time of collectivization, villages of this valley in the Altai witnessed a gory major overhaul of social relations. The richest collection of early printed books and manuscripts the peasants had been gathering since the reign of Katherine the Great was doomed. The books wintered in a barn without a roof; a few bottom volumes sank in the snow and were not noticed when the unique library was being carried away to be barbarously burnt. In the spring, a local peasant woman found them and took them home. Four decades later, I was looking at one of the manuscripts she had saved. The winter spent under the snow told on the book: its pages glued to form a monolith, not a single water sign could be seen. The book opened only in two or three places, and on one of them I discovered a date, 1591, the year when one of the works was written. This was The Life of Saint Blessed Prince Alexander Nevsky, a well-known monument of Old Russian literature.After the book was dried in the shade for a short time, a few pages came apart almost completely, and I spotted a line that proved the importance of our find: “and Metropolitan Daniil asked Maximus of Mount Athos…” So this was the famous Dispute of Metropolitan Daniil and Maximus the Greek, also known as The Trial Record of Maximus the Greek. Only one copy of the monument dated mid-17th century had been known; it contained numerous discrepancies and paralipses and broke off on the Metropolitan’s accusatory speech. The prosecution argument had long been known to historians whereas Maximus’s defense was obscure. Scholars in this country and abroad could only guess what the second half of the source might have been about. So the excitement I felt when I saw that we had purchased the book containing a manuscript of Maximus the Greek’s Trial Record was understandable. It was clear at first sight that the manuscript was much older than the one known. The other big question was if it would be more complete. We were able to estimate the rough volume of the part that interested us as soon as the upper corners of the glued leaves began to come apart. The beautiful compact cursive writing characteristic of the monument took twice as many pages as the known part of Trial Record could have taken!

(From N. N. Pokrovsky’s book Quest for Rare Books, Ch.4)

For instance, the book from Father Palladius’s collection – our first expedition find – referred to the works of unknown writers like Miron Galanin, bond slave Maxim, and steward of Demidov and Osokon’s factories Rodion Nabatov. We have managed to find out a lot of interesting facts about each of them.

Rodion Nabatov, for example, was not only a steward but also an expert in mining. His name is associated with the discovery of silver mines in the Altai and construction of smelting factories in the Urals and in the Altai. At the same time, he was a secret Old Believer and ably conducted a number of operations for the rescue of Old Belief leaders, in particular, the well-known starets Ephrem. Nabatov himself was finally arrested and reportedly passed away in confinement or, according to other sources, was given back to his first master in the Trinity Monastery of St. Sergius.

INDICOPLEUSTES IN THE ALTAI

The hermits and peasants living on the banks of the River Uba in Altai still honor the book that was well known to an early medieval reader. It is Christian Topography by the Syrian monk Cosmas Indicopleustes – a kind of encyclopedia of the geographical and cosmological knowledge of the ancient world. Written in the middle of the 6th c., it was translated to Russian at the threshold of the 11th and 12th centuries.Cosmas not only developed his views, which can be traced back to Ptolemy, on the geocentric structure of the Universe and retold many of the Bible’s pages but narrated his journeys that took him as far as India. The richly illustrated stories about the island of Venice, Indian aborigines and fairy animals such a unicorn, a boar-elephant and a water horse were very popular with readers.

The manuscript given to me as a farewell gift by Mother Athanasia was easy to date thanks to the blue paper as written in the 19th c., but the handwriting and numerous illustrations showed that its creator did his best to make a close replica of the 16th-century manuscript. Abounding in high quality drawings, this book must be our brightest find on the Uba.

(From N. N. Pokrovsky’s book Quest for Rare Books, Ch.9)

This is just one of the countless examples. Any name mentioned in the book involves a long and thorough search in archival depositaries and libraries allowing opening up the lives of people who were not known.

Written on birch bark

Talented Old Believer writers do not belong exclusively to the 18th century. In 1988 I happened to meet Afanasiy G. Murachev, the author of a number of polemic works, including these about the destruction brought upon nature by the modern high-tech civilization. He took an active part in producing the three-volume Genealogy of the Ural-Siberian Chasovennoe Soglasie and wrote a bright autobiography.

THE BOOK OF ROYAL DEGREES

In 1977, while working in the depositary of Tomsk Regional Studies Museum, N. N. Pokrovsky discovered what later proved to be the oldest copy of The Book of Royal Degrees, the first attempt to give a general view on Russian history made during the reign of Ivan the Terrible.Water signs on the paper indicated that the manuscript could have been dated by 1550—1560; the last events described in the book referred to the years 1560—1563.

The Tomsk copy turned out to be contemporary with the Chudov copy known earlier. In 2001, A. V. Sirenov, a St Petersburg scholar, added another copy of the time, the Volkovsky one. Comparison of the three manuscripts showed that the handwriting, paper, and proof on the margins were identical. It looked like all the three manuscripts were on a desk of the Chudov monastery scriptorium in the Kremlin at the same time.

We had a unique textological situation, which required a new look on the history of creation of the famous monument. The existing copies were supplemented by another three (dating from the late 16th to the early 17th c.), and scholars led by Pokrovsky started to investigate and compare the copies.

As a result of meticulous work of specialists from St Petersburg State University, State Historical Museum, and Institute of History SB RAS, all marks, corrections and distinctions between the variants, so important for recreating the author’s idea and understanding its further development, were taken into consideration.

In 2007—2009, a complete two-volume edition of the monument was issued, which opened for academics the route to the inception of the manuscript that has had a great influence on the native science of modern history. The third volume containing commentary is being prepared by Professor of the University of California G. Lenhoff

The focus of many of his works is one of the most tragic episodes of his life – destruction by an NKVD detachment of the main skete of Chasovennyie on the Lower Yenisei in 1951, arrest and massacre of the skete inhabitants, and burning of the unique collection counting over 500 ancient Russian books. Quite an authentic description of this story is given by A. I. Solzhenitsyn in The Gulag Archipelago.

There is also some evidence left by the victims but the most detailed and touching story about these events belongs to Murachev.

Having learnt that Afanasiy Murachev knew how to prepare birch bark for writing in ink, the archaeographers asked him to write on it something about those turbulent events. Historical sources dating from the 17th c. contain several references to the effect that in Siberia, because of a lack and high price of paper, they used to use birch bark. They would not only write business-like notes and prayers on it, as it had been the case in Veliky Novgorod, but also vast texts of Siberian chronicles. Regretfully, the birch bark books have not survived to our day; it is only recently that some short texts written in a Tomsk skete have become known.

In the end of 1991, a book arrives in Academgorodok from the Yenisei taiga made of 18 sheets of finely processed birch bark. Apart from the four rhymed stories by Afanasiy and monks Vitaliy and Macarius about the events of 1951, it contained several more texts including spiritual and moralizing poems, versed messages to nuns, and an acrostic about the importance of reading.

URAL OLD BELIEVERS

The plan of releasing Starets Ephrem was elaborated by Rodion Nabatov, who paid special attention to setting up a network of places where Ephrem could hide after the escape. Rodion sent hundreds of rubles all over West Siberia and the Urals. The preparations took about three months. At last, everything was ready. Transfer horses were waiting for Ephrem’s arrival all along several route options. The first sledge would be at the ready right under the walls of the Tobolsk Kremlin. The most dangerous part of the plan left to be done was to prepare everything inside these walls. There, Rodion had to see and work out everything himself. So he got inside the Kremlin and the prison, where he told Ephrem about all the details and date of the escapade.At 11 p. m. of December 19, Starets Ephrem was led along the prison corridor back to his chamber. “For some reason,” shackles had been taken off from his ankles, only shackles on the wrists were left, and he was accompanied by a single guard. They stopped near the Kremlin wall, next to a narrow gun-slot, normally shuttered. On that day, however, they were removed. Afterwards, the guard, subject to severe torture, would claim that he knew nothing about the escape. He only turned back to relieve himself and suddenly noticed that Ephrem had disappeared.

The hand-shacked sixty-year old man threw himself out of the gun-slot, rolled down the snowed under 50-meter hill on which the Tobolsk Kremlin was located, and down there a sledge was waiting for him. However hard military teams sent out in all directions tried to find him, they failed.

(From N. N. Pokrovsky’s book Quest for Rare Books, Ch.3)

Taiga Xerox

In the Soviet times, a colossal number of cultural artifacts including ancient books were destroyed: for many years we proceeded from one scene of a fire to another. Today, there’s a new problem – private book dealers. We can only hope that the books they acquire will show up one day if not in the noted state libraries (for them, the prices are prohibitive), then maybe in a private collection whose owner will be a genuine lover and true connoisseur of ancient Russian books.

Most of the books our department gets today result from the old, long-established relations. The times are changing though and field archaeography does not remain intact either. For example, residents of one of the most secluded sketes based on the Yenisei River found out that they had relatives in the USA and Canada – in the time of persecutions Old Believers had settled all around the Old and New World.

The skete residents established relations with their relatives and began corresponding with them. The adherents from abroad became frequent quests: a helicopter would land on the forest clearing, first a power generator and then a Xerox machine appeared in the skete... And now we can easily get some opuses, sometimes unique: the Old Believers send us either a copy or the book itself provided that we return it after a dozen of copies have been taken. It is in this way that we came to possess the Old Belief book polemics of the 21st c.

"MAGIC BOOKS"

In one of the Old Believers’ settlements notorious from time immemorial for its sorcerers, I heard that thirty years ago somewhere in those parts they had a handwritten copy of the book known all over Russia – The Great Science by the Aragon philosopher of the 13th c. Raimondus Lullius. A former poet who became a rigorous ascetic and a preacher, he tried to create “the great science” – a unified system that would logically explain all dogmas of Christian ideology and truths of positive sciences. His numerous disciples and followers, in the process of copying his work, added plenty of new information, especially in the field of astrology and magic. In this way, Lullius posthumously became a great authority in this sphere, mostly alien to him.My attempts to find the Raimondus Lullius’s book during the expeditions were to no avail, but in Siberia I saw for myself more than once that the magic charm texts were an important ingredient of peasants’ book culture. Despite the strict bans on everything connected with magic and sorcery, even the harshest old men would quote from memory some lines from these books. For a long time I searched for “magic books” in the archives, and asked about them old timers dwelling in remote forest and mountain settlements, and finally I succeeded. In the Central State Archive of Ancient Acts in Moscow I saw the case of doctor’s apprentice Molodavkin. This was quite a brief case – about 50 pages of standard 18th-century secretarial shorthand – and a small envelope with a broken wax seal. And in it was what I had been searching for, a true “magic book.”

Ivan Molodavkin, an apprentice of the Izmailov regiment doctor, had borrowed it from the peasant Matvei Ovchinnikov in order to copy a charm “to make gals love him.” The “magic book” proved to contain a string of love charms, from comparatively neutral to the church doctrine to the ones that had formulas of direct denial of Christ and transfer to Satan’s power. Awash with bright images and poetical similes, they produced a strong impression on the reader.

(From N. N. Pokrovsky’s book Quest for Rare Books, Ch.6)

Let us remember that the Old Belief literary tradition traces back, among other things, to the dispute about how to put fingers for making the Sign of the Cross and for blessing. In today’s New World, these arguments have reached the subtlety Protopope Avvakum could not have dreamt of. Like in the bygone times, representatives of different camps exchange envenomed messages abounding in quotations from Byzantine and Old Russian literature. We have started publishing these highly curious texts.

The Institute of History’s collection of early printed books and manuscripts counts about 2,000 items.It includes copies, dated from the 16th to the 20th c., of many well-known monuments of Old Russian literature. These are the texts of hagiographic, historical, so-called scientific and other genres traditionally valued by Russian medieval men of letters.

The collection has a good representation of Old Believers’ books. Traditionally, these included samples of patristic literature, exegeses of Apocalypse, hermits’ sayings, etc. A considerable part of the archive has been introduced for academic use. Two volumes of Description of Manuscripts from the Institute of History SB RAS Collection have been released (in 1991 and 1998), and the third volume has been prepared for publication.

For the electronic version of the Description, see the Institute’s website. The texts of the Collection are published in the series Siberian Archaeography and Source Studies and History of Siberia. Sources

Why am I so interested in Old Believers? It is these people who have preserved, very carefully and often putting at risk their own lives, ancient manuscripts dated from the mid-17th c., when many of the church books published prior to the Nikon reform were banned by the government. A considerable part of Old Russian books kept in the Moscow and St Petersburg libraries and depositaries and of the famous Russian icon collections of the Tretyakov Gallery and Russian Museum used to belong to Old Believers. .

They have managed not only to keep but to continue the Christian literary tradition. Their opuses reveal the features of people’s religious consciousness underlying which is the Orthodox Belief with a number of distinguishing traits, similarly to the nowadays frequently mentioned people’s monarchism.

We began dealing with these issues earlier than many others. This was possible due to the relative ideological freedom Academgorodok of Novosibirsk safeguarded by the then head of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences Academician Lavrentiev, whom I asked for help more than once. They informed against me and requested my dismissal from the University, but Mikhail Alekseyevich would always take my side.

Thanks to his efforts, as well as to the support of our colleagues from Moscow and Petersburg, in particular Academicians D. S. Likhachev and S. O. Schmidt, our archaeographic center carried on: expeditions were organized, literary monuments published, and research conducted – and the map of Siberian Old Belief had fewer and fewer blanks left...

References:

The Book of royal degrees based on ancient copies: texts and commentary / Ed. Pokrovsky N. N., G. D. Lenhoff. M.: Iazyki slavianskih kultur, 2007. V. 1; 2008. V. 2.

Pokrovsky N. N. Anti-feudal protest of Ural-Siberian Old Believer peasants in the 18th c. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1974. 394 p.

Pokrovsky N. N. Quest for rare books / 3rd edition, revised and suppl. Novosibirsk: ID Sova, 2005. 339 p.

Records of Maximus the Greek and Isak Sobaka / Prepared for publ. N. N. Pokrovsky; ed. S. O. Schmidt. M.: Izd. GAU SSSR, 1971. 186 p.

The photographs used in the publication are from the archive of the Institute of History SB RAS and from the personal archive of N. N. Pokrovsky

The editors thank the Institute of History SB RAS employees Doctor of History N. D. Zolnikova, Doctor of History A. Ch. Elert, Candidate of History Ye. V. Komleva, Doctor of Philology T. V. Panich, and Doctor of Philology O. D. Zhuravel for their assistance in the preparation of this publication