The Latukhin Book of Royal Degrees: History of the United State of Russia

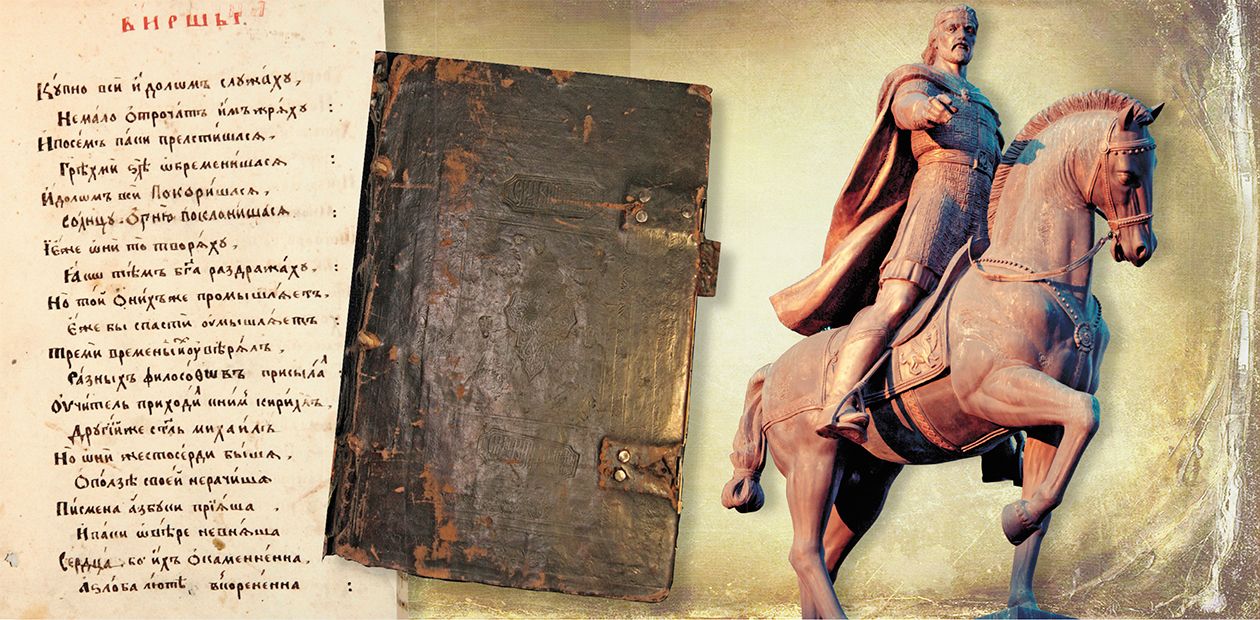

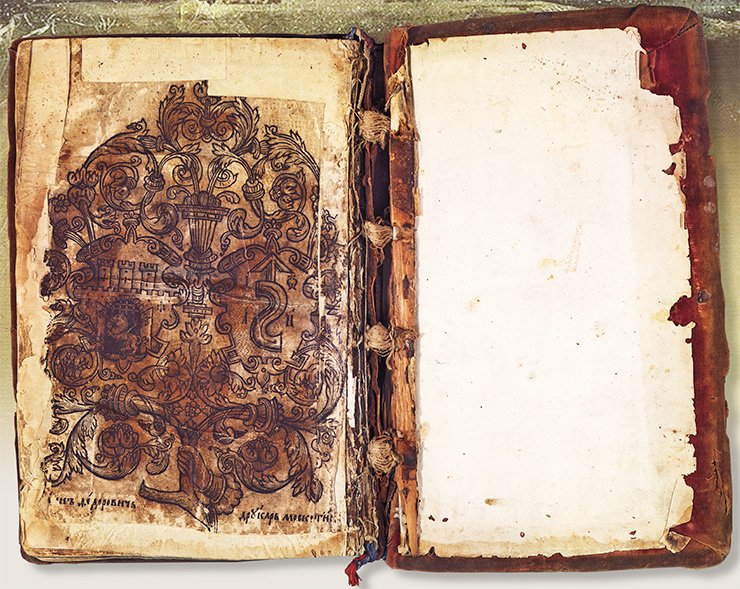

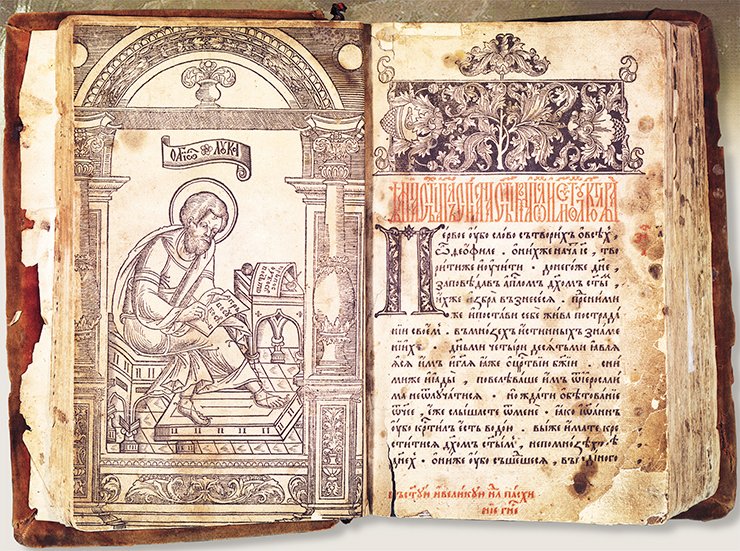

We have already written (#3, 2010) about the Tomsk find – the discovery of the oldest copy of “The Book of Degrees of Royal Genealogy.” Written in 1563, at the time of Ivan the Terrible, the book was the first attempt to present a general view of the history of the Kingdom of Moscovia within its then boundaries.

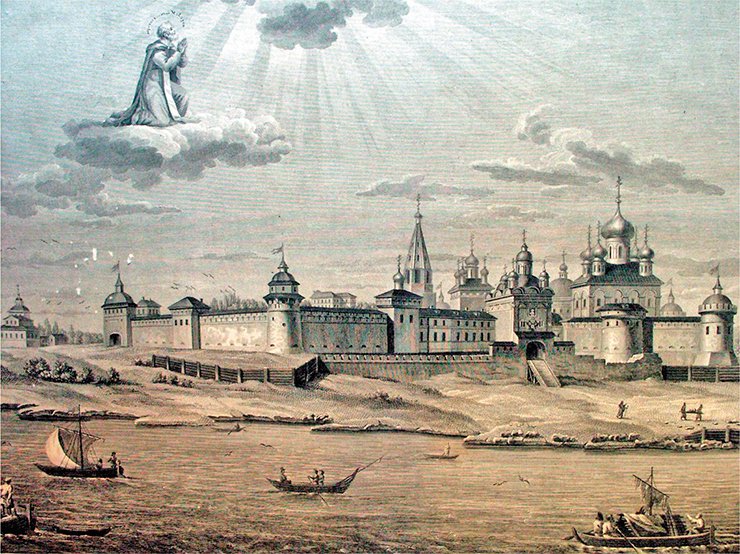

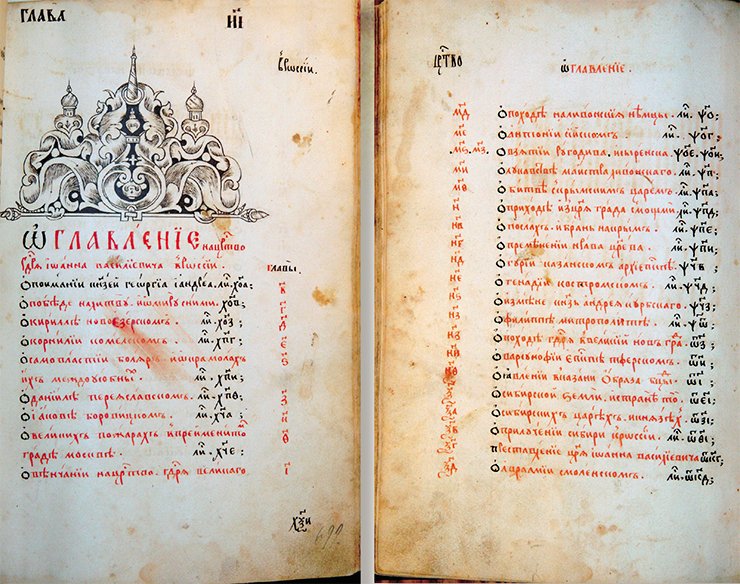

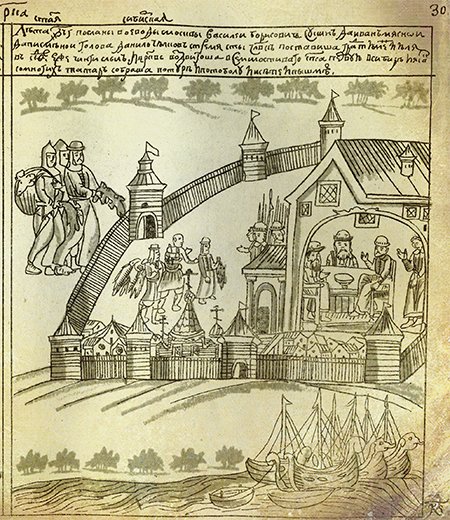

More than a hundred years later, in 1678, a literary milestone was produced whose principal structure copied that of “The Book of Royal Degrees”: the account of events was based on the “degrees” – rules of the Russian great princes and tsars. At the same time, the new book noticeably expanded the chronological and geographical borders of national history. The author of the book was a clergyman, poet, historian and music scholar Tikhon Makarievsky, archimandrite of the Makariev Zheltovodsky Monastery near Nizhny Novgorod.

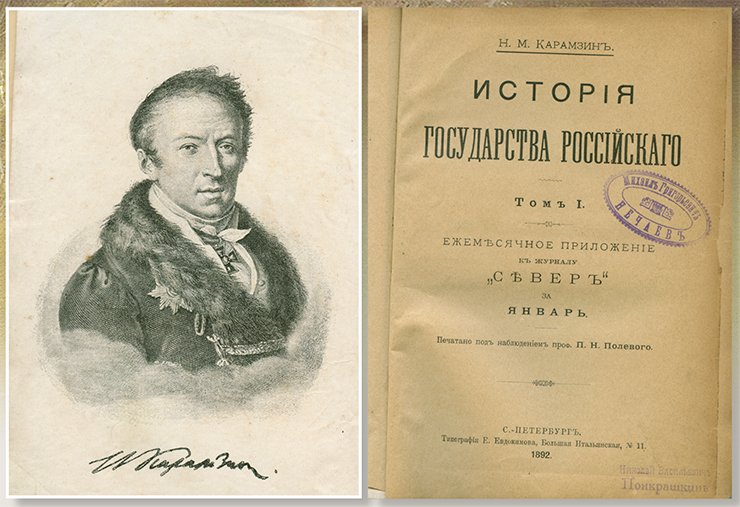

In the early 19th century, the work of archimandrite Tikhon was given to the famous Russian historiographer N.M. Karamzin by the merchant Latukhin from Balakhna, the person after whom the book is named. Though “The Latukhin Book of Royal Degrees” was widely used by historians and in the late 19th century the question of its complete publication was raised, the text of the great work remained unpublished.

In 2011, Academician N N. Pokrovsky (Institute of History, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk) and Doctor of History A.V. Sirenov (Saint Petersburg State University) prepared the first edition of this outstanding corpus of Russian history written on 1268 large sheets (recto and verso)

The authorship and the time of creation of The Latukhin Book of Royal Degrees and of its Nizhny Novgorod copy are unambiguously indicated in the book itself. It opens with Verses written in the acrostic form: “Monk Tikhon began this book Deo favente, wrote it easily, received sufficient wages for it, took it to the Zheltovodsk Monastery in the year seven thousand one hundred and eighty seven in the month of November…” (1678).

Archimandrite Tikhon must have been born in Nizhny Novgorod; it is difficult to say why he headed his beloved monastery only for two years but his departure did not mean the end of his career and varied activities. Immediately after leaving the Zheltovodsk Monastery, he was appointed the archimandrite of the New Jerusalem Resurrection Monastery but, having hardly taken this new position, on January 19, 1680 was designated as cellarer at the Savvo-Storozhevsky Monastery. This cloister enjoyed special favor of the young tsar Feodor Alekseyevich and of the patriarchal court. Tikhon served as purser with the last Patriarch Adrian, and was then his executor. His proximity to the top clerical and secular authorities could not but influence the prevailing tendencies observed in The Latukhin Book of Degrees. Another strong impact came from important realities of the time, primarily, successful completion of the main stage of Great Russians’ struggle for reunification with the two other Eastern-Slavic peoples, Ukrainians and Byelorussians.

When writing his work, archimandrite Tikhon kept to the structure of The Book of Degrees, based on the rules of Russian sovereigns (“degrees”), but he heavily edited the 16th-century text proceeding from the new view of the past events and, above all, he added new sections to describe the gloomy years of Ivan the Terrible’s rule, the murder of the head of the Russian Church Philip Kolychev, defeat inflicted by the tsar on Great (Velikiy) Novgorod, the end of the Rurik dynasty, the beginning disintegration of the country at the Time of Troubles and Russia’s revival, and the rule of the first Romanov and of his son Tsar Aleksey Mikhailovich.

A most important in novation was the inclusion in national history of the facts on the past of the territories that had joined the State of Russia quite recently: the Kazan Khanate, Siberia and the old Slavic lands of Ukraine and Byelorussia, for which Russia had fought hard wars with Lithuania and Poland for several centuries.

In 1902, a meticulous researcher of The Latukhin Book of Degrees, P.G. Vasenko made a successful attempt at dividing it into three voluminous parts: the first comprised the chapters corresponding chronologically to The Book of Degrees (until late August 1560); the second gave an account of the events of the end of rule of Ivan the Terrible, from the memorable chapter “On the change of the Tsar’s temper” to the end of the Time of Troubles is; and the third part contained stories of the rules of the first two Romanovs (some later copies of the book go as far as the rule of Peter II).

In 1902, a meticulous researcher of The Latukhin Book of Degrees, P.G. Vasenko made a successful attempt at dividing it into three voluminous parts: the first comprised the chapters corresponding chronologically to The Book of Degrees (until late August 1560); the second gave an account of the events of the end of rule of Ivan the Terrible, from the memorable chapter “On the change of the Tsar’s temper” to the end of the Time of Troubles is; and the third part contained stories of the rules of the first two Romanovs (some later copies of the book go as far as the rule of Peter II).

For many years it was the second part of the book that attracted most attention on the part of historians. N.M. Karamzin paid attention to a string of unknown texts dwelling on the events that occurred in the 16th and 17th cc., especially at the Time of Troubles The scholars used them in his History of the State of Russia, thus familiarizing the society of his day with many facts and opinions of the Zheltovodsk archimandrite. As noted long ago, A.S. Pushkin based his drama Boris Godunov, to a great extent, upon these texts by Karamzin, dating back to archimandrite Tikhon’s work.

Considering them original and having no earlier sources, Karamzin actively introduced them for scholarly work. However, S.F. Platonov and his followers revealed the sources of the overwhelming majority of the texts from The Latukhin Book of Degrees (Platonov, 1913). These are The New Chronicler, Avraamiy Palitsyn’s Story, the second edition of The Chronograph, The Tale of how Boris Godunov Crookedly Took Possession of the Tsar Throne in Moscow…, and The Story and Tale of the Events that Happened in the Reigning Town of Moscow and of Unfrocked Monk Grishka Otrepiev… In wide chronological frames, the book also used Savva Yesipov’s chronicle On Siberia and on Taking over Siberia together with its continuation in The Siberian Chronicle as well as some proceedings from Nizhny Novgorod, Astrakhan and Nogai.

“Gloomy years” of Ivan the Terrible’s reign

An invaluable corpus of historical events is contained in the 17th “degree” of The Latukhin Book of Degrees, dedicated to the “gloomy” period of the reign of Ivan IV, which began in the 1560s and ended with his death in 1584. The dismal events described by the author do not agree with the tsar’s pious image embodied on The Book of Degrees pages.

Beginning with Chapter 53, typically entitled “On the change of the Tsar and Great Prince Ioann’s temper,” Tikhon Makarievsky dwells in great detail on the atrocities performed by the oprichniks headed by the tsar, including the plunder of Moscovia’s second largest town, Velikiy Novgorod, a principal front-line center that procured the Russian troops during the unfortunate for them Livonian War, and the sacrilegious murder of the head of the Russian Church metropolitan and great martyr Philipp Kolychev by Maluta Skuratov, leader of the oprichniks and the tsar’s local servant, an act in sharp contrast with The Book of Degrees’ main idea of the “symphony” between the Church and the state.

The change from eulogies sung to the tsar to his rebuke is quite sharp, despite all the author’s attempts to soften it. Now Tikhon reports the victories of Russian warriors in the East and in the West, writes about the good works of the “Christ-loving tsar of Moscow and all Russia” like his giving a helping hand to the patriarch of Constantinople Dionysius and to the Hilander Monastery on Athos or the renovation, on the tsar’s order, of the Danilov Monastery. And right after this rendering of chapters from The Book of Degrees infiltrated with the historical ideology of its authors – metropolitans Macarius and Athanasius – the Zheltovodsk archimandrite has to address the events of a completely different tone.

To explain this abrupt transition, Tikhon takes as the basis of Chapter 53 the text of the Russian Chronograph of 1617, which attributed the change in the tsar’s nature to the death of his beloved wife Anastasia Romanova, who had produced a salutary effect on the tsar’s disposition: “She inclined Ioann Vasiliyevich to virtue and appeased his temper” (sheets 822 verso and 823). Archimandrite Tikhon embraces every opportunity to praise Anastasia, whose personality in the centuries to come connected the Rurik and the Romanov dynasties. In The Life of Reverend Gennadius of Kostroma and Lubim, which makes part of The Latukhin Book of Degrees, he inserts the story about the Saint’s prophesy pronounced in the house of Boyar Yuliania, the mother of Anastasia. Addressing the future tsarina, he says, ‘“You are a fair birch and a fruitful branch, you will be our sovereign lady blessed for the entire world,” and so it was, adds Tikhon, according to his prophesy, with God’s grace’ (sheet 830 verso and 831).

ON RECEIVING ROYAL REGALIAThe Latukhin Book of Degrees gives two versions of this event. At first it says that Vladimir Monomakh got hold of the royal regalia in Crimea, when he captured the elder of Caffa (the old name of Feodosiya), whom “Vladimir dismounted with the help of his spear and brought him tied-up to his regiment and spoiled him” of his neck-piece, belt and hat “for the sake of initiation to reign and coronation of the pious sovereign of Russia” (sheet 153 verso). Later on, however, archimandrite Tikhon enunciates a different, much more solemn version of receiving the royal regalia from the Byzantine emperor Alexios Komnenos through Neofit, metropolitan of Ephesus (sheet 154). It was this version that became the most widely-spread in the Moscow concepts of the “Third Rome”

Indeed, Anastasia’s death in 1560 was a great blow to the tsar though it would be an exaggeration to attribute the change in his policy to this private tragedy. Nevertheless, this explanation became widely spread after Ivan IV died, and The Latukhin Book expresses it quite strongly: “After her death a great storm broke out in the tsar’s virtuous silence, and his wise mind changed to furious temper. And he began to destroy many of his relatives and dignitaries. As it was said in the Parables, ‘Lust changes placable mind.’” (sheet 822 verso).

The author of The Latukhin Book of Degrees could not overlook the event that led to the demise of the ancient Rurik dynasty and that, in the author’s opinion, was the main reason for the Time of Troubles – the murder (in 1581) by Ivan the Terrible of “his elder son tsarevich Ioann, full of wisdom and virtue,” whom his father tore off from the branch of life like a strong wind tears off an unripe cluster” (sheet 823 reverse and 824).

After these lines comes the first mention in the book of Boris Godunov, who “dared to enter the tsar’s privy chambers” to ask after the heavily injured Tsarevich Ioann. For this, the tsar flew into rage and tortured him and inflicted a great many injuries on him.” Later, he regretted his deed and having found out that Boris was treated by the merchant of Great Perm “called Stroganov,” “ordered to style this merchant higher than a guest merchant.” And from that time the Sroganovs became court nobility” (sheet 825 verso). In the above story, the only historically correct fact is the murder by the tsar of his heir, but historians might be interested in the author’s attempt to give reasons for the remarkable promotion of the Stroganovs, who are known to have fitted out Yermak’s expedition to Siberia. Another thing worthy of note is that this story about Godunov’s noble behavior contradicts Tikhon’s general tendency to rebuke this character sternly as an adversary of the Romanovs.

After these lines comes the first mention in the book of Boris Godunov, who “dared to enter the tsar’s privy chambers” to ask after the heavily injured Tsarevich Ioann. For this, the tsar flew into rage and tortured him and inflicted a great many injuries on him.” Later, he regretted his deed and having found out that Boris was treated by the merchant of Great Perm “called Stroganov,” “ordered to style this merchant higher than a guest merchant.” And from that time the Sroganovs became court nobility” (sheet 825 verso). In the above story, the only historically correct fact is the murder by the tsar of his heir, but historians might be interested in the author’s attempt to give reasons for the remarkable promotion of the Stroganovs, who are known to have fitted out Yermak’s expedition to Siberia. Another thing worthy of note is that this story about Godunov’s noble behavior contradicts Tikhon’s general tendency to rebuke this character sternly as an adversary of the Romanovs.

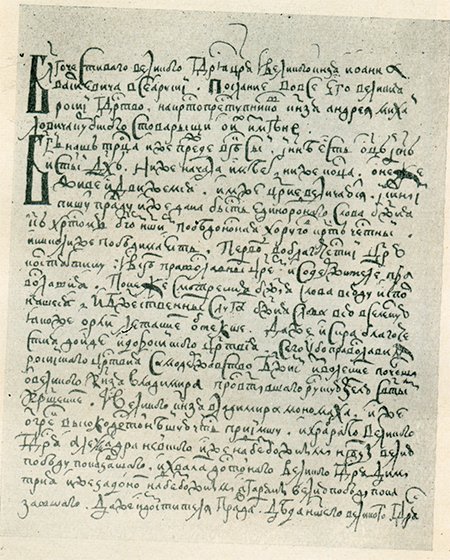

Towards the end of the account of the tsar, originally wise and later insane and furious, Tikhon inserts three well-known tales of the 16th c., narrating the wrong-doing of Ivan the Terrible: the first letter of Andrei Kurbsky to the tsar, the Life of Metropolitan Philipp Kolychev and the terrifyingly realistic The Tale of the Tsar’s Nizhny Novgorod Campaign (Chapters 56—58). At the same time, the author pays some respect to Rurikovich. For instance, preceding Kurbsky’s accusatory words addressed to the tsar with “leprotic conscience one cannot find even with irreligious peoples,” is the title “On the betrayal of Prince Andrey Kurbsky,” which is substantively right.

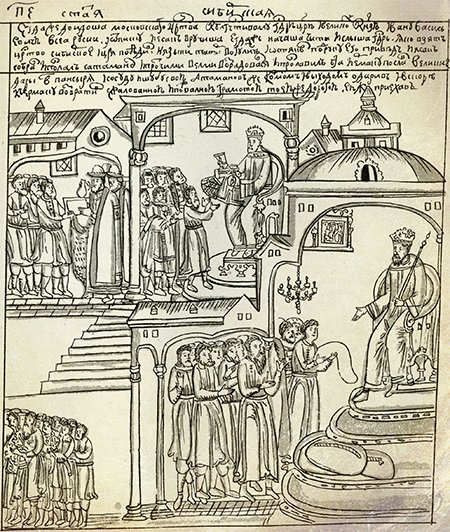

With great solemnity Tihkon Makarievsky begins his story about the last tsar of the Rurik dynasty – Feodor Ioannovich, a gentle and god-fearing ruler. “Of righteous root good and virtuous shoot, wise in God, pious Tsarevich and Great Prince Feodor Ioannovich of all Russia,” writes Tikhon in the “degree” dedicated to Feodor Ioannovich (sheets 865—917). A tenth of the story comes not from a narrative but from a documentary source, of both religious and secular nature, The Coronation Rite of Feodor Ioannovich (sheets 866—872 verso). The solemn and deliberate account of the magnificent spectacle that took place in the Kremlin’s churches and chambers contrasts sharply with the emotionally horrible scenes of the previous “degree” about the harsh reprisals carried out against the citizens of Velikiy Novgorod by Ivan the Terrible.

Time of troubles

The gravest events for the country of the Time of Troubles (1598—1613) were described by archimandrite Tikhon mainly on the basis of the Avraamiy Palitsyn’ Story, an active participant of the 16-month defense of the Trinity and St. Sergius Monastery, besieged by detachments of Polish war lords Sapega and Lisovsky. The vigorous cellarer played an important role during the decisive combat for Moscow against Hetman Jan Karol Chodkiewicz. It was he who managed to bridge the gap between the leaders of the Second Militia Pozharsky and Minin, and the remains of the First Militia, Cossacks of Trubetskoy. At the time of the decisive battle for Moscow, his heartfelt sermon brought out patriotic feelings in the Cossacks, and they decided to help liberate Moscow.

Later, Patistyn tried to persuade the Cossacks to continue the siege of the Kremlin and of the Belyi Gorod (White City) until they were finally defeated. When the Cossacks required their wages to be paid immediately, Avraamiy took a gold plate from the monastery and brought it in two horse-drawn carts to the camp of besiegers near Moscow. Ashamed of their behavior, the Cossacks returned everything to the monastery and carried on the siege of the Kremlin.

The author of The Latukhin Book of Degrees tells an amazingly vivid and detailed story of how devastated Russia was during the Time of Troubles, how close it was to the brink of a precipice, and how much military force it took to move it away from that precipice. After Moscow had been liberated, for a number of years the bleeding Russia deterred attacks of invaders trying to get to the capital and continuing the plunder of Russian towns. It was only the togetherness of citizens, the tenacious perseverance of Russian warriors and the passionate appeal of the Church that let the country survive.

ON PEACEFUL SLAVS AND BELLIGERENT MUSLIMSThis refers in particular to stories, borrowed from Synopsis and other sources, about the word “Rossy” originating from “rosseyany” (in Russian, “scattered over a huge area”); Slavs being named “in memory of the glory (in Russian, “slava” stands for “glory”) of Slavic people, as well because of their origin from “princes Sloven and Rus” (sheet 14); the Sarmatians coming from Asarmat or from Sarmof, great great son of Arphaxad, the son of Shem.” According to archimandrite Tikhon, the name of the town of Moscow derives from the name of Noah’s grandson Mosoch (sheets 18 verso—19 verso), and the name of Astrakhan from the ancient Slavonic Tmutarakan: “In Astrakhan, previously called Tmutarakan, Prince Mstislav, son of equal to the apostles sovereign Vladimir, erected a church in the name of Holy Mother” (sheet 796).

The following is the mythological, allegedly Old Testament, explanation of the Slav’s peaceful nature and Muslim belligerence: the latter “were severe towards us because their ancestors, Ishmael and proud Esau, blessed them to fend for themselves with their weapons. And we are humble as we come from our ancestor Jacob, and therefore we cannot withstand them properly but humble ourselves in front of them, like Jacob in front of Esau. We can only defeat them by virtue of God’s blessed cross, this is our victory in battles over our enemies, Ishmael’s descendants” (sheets 734 verso—735).

Generally, the Zheltovodsky archimandrite writes continuously about the role of the Church in Russian history and the importance of the Orthodox moral code for the people. His book includes the Lives of 120 Russian saints, from Saint Princes Olga and Vladimir, elders of the Kiev-Pechersk Monastery to St Sergius of Radonezh and men of faith who lived in the 17th century. Tikhon recounts in great detail the deed of martyr Patriarch Hermogenes, who gave his life for active action against Polish invaders, for his refusal to approve putting the Polish prince Władysław on the Russian throne and for his fervent appeal to the citizens of Russian towns to unite and liberate the capital and the entire country.

Zemsky sobor (Assembly of the Land) that marked the end of the Time of Troubles met in January 1613 to elect a new tsar to the throne. Tikhon stresses its estate-representative nature and wide participation of various groups of the population: “From all the towns of the Russian Land people came to the eminent reigning city of Moscow: princes and boyars, merchants and trading people, hetmans and cossacks, chiefs and soldiers of different ranks – all handed in signed proposals on electing the tsar” (sheet 1092). The Makarievsky archimandrite gives a picture of serene unanimity of all congregations of the Assembly, casting a veil over the disputes about the candidates to the throne. According to him, all of the signed proposals had just one name, that of Mikhail Feodorovich Romanov.

Reunification of East Slavs

Crucially important for incorporating western lands into the State of Russia were the following events that occurred in the 17th c.: the Russian-Polish war of 1648—1654, the Treaty of Pereyaslavl of 1654 and the Truce of Andrusovo of 1667, according to which Russia secured the whole of the Left-bank Ukraine and the capital town of Kiev.

It should be noted that the struggle for the western lands was a heavy financial burden for Russia. Voluminous archives of the Sibirsky prikaz (a governmental establishment of the 17th—18th cc. Russia in charge of administrative, judicial, financial, economic and other issues throughout Siberia) contain quite a few documents of that time, statements of expenses and receipts concerning the Ukrainian matters. It was the Siberian “currency,” sables, which became the most important finance source for both military campaigns and the subsequent peaceful activities intended to maintain the administrative order at the recovered lands.

In the 17th c., when the Time of Troubles was over, the cultural links between Moscovia and the Ukrainian orthodox elite strengthened, gaining a new property. The struggle of Kiev’s academic clergy against imposing Union and Catholicism by the Lithuanian-Polish authorities commanded the sympathy of the Russians. As early as the 1640s, polemical works of Ukrainian Orthodox Christians were reprinted and enjoyed great popularity. Even before that, the Russian capital was influenced by Ukrainian school education and scholarly educational centers like Kiev-Mohyla Collegium (later Academy), which put an emphasis not only on rhetoric and poetry writing but also on Aristotle’s logic.

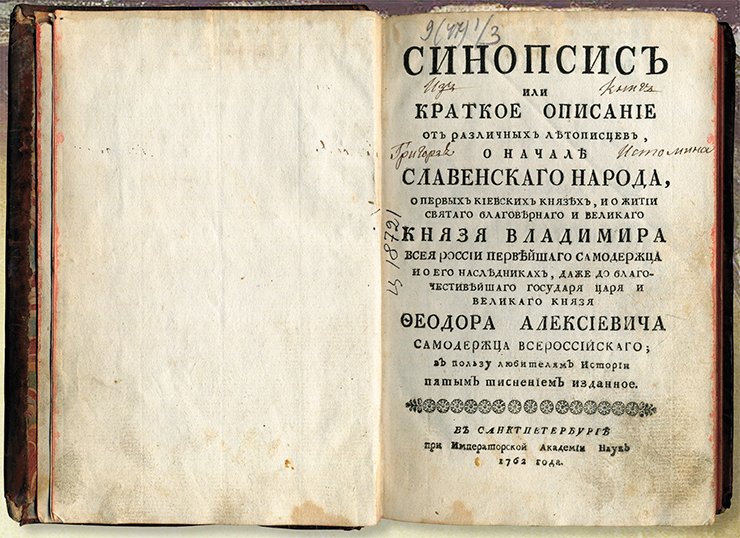

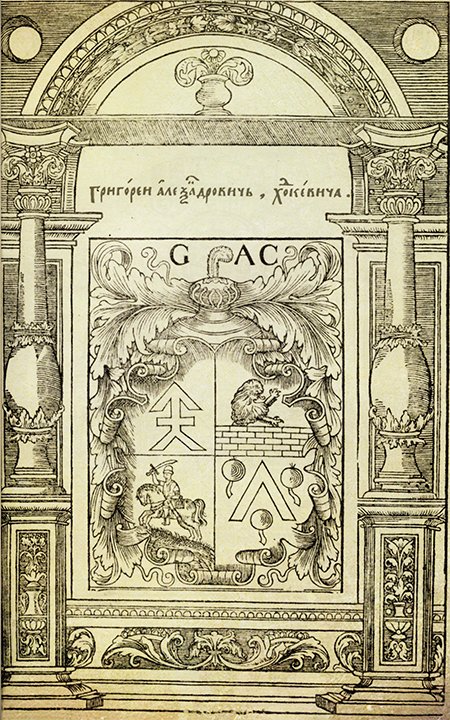

In 1671 the Rector of this collegium Innokentiy Gizel wrote Synopsis, dedicated to the history of East Slavs and dwelling on the unity of Great Russia and Little Russia. The book became very popular and enjoyed many editions. It was this work that archimandrite Tikhon took as a basis of The Latukhin Book of Degrees’ sections dedicated to the history of the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia, the joint struggle of East Slavs against the Tatar-Mongol oppression, and succinct but exact data on Kiev rulers within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. For instance, on sheet 796 archimandrite Tikhon thought it appropriate to place the following statement: “In the same year (1555) Kiev’s governor was Grigoriy Aleksandrovich Chodkiewich.”

In 1671 the Rector of this collegium Innokentiy Gizel wrote Synopsis, dedicated to the history of East Slavs and dwelling on the unity of Great Russia and Little Russia. The book became very popular and enjoyed many editions. It was this work that archimandrite Tikhon took as a basis of The Latukhin Book of Degrees’ sections dedicated to the history of the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia, the joint struggle of East Slavs against the Tatar-Mongol oppression, and succinct but exact data on Kiev rulers within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. For instance, on sheet 796 archimandrite Tikhon thought it appropriate to place the following statement: “In the same year (1555) Kiev’s governor was Grigoriy Aleksandrovich Chodkiewich.”

Nor did the author neglect the heated topic of struggle between Moscow and Lithuania for East Slav lands, using data contained in both Russian Chronicles and The Book of Degrees and in the brief texts of Synopsis. Curiously, unrestrained praise for the “tsars of Vladimir, Moscow and all Russia” agrees well with similar praise sung to the “tsars of Galicia and all Russia.” The author does not even make an attempt at explaining this controversial information, leaving this uneasy work for the future generations of historians.

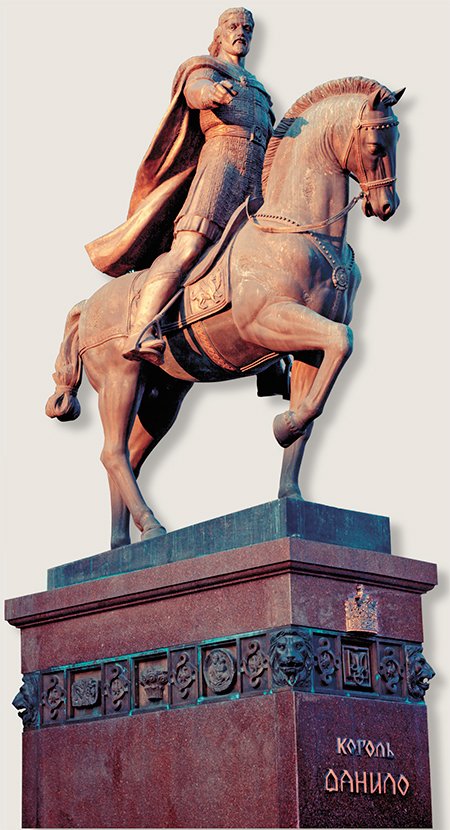

Notably Tikhon Makarievsky pays homage to the famous ruler Daniel of Galicia (died in 1264), Prince of Volhynia and Galicia and the first king of Rus’. There is an embarrassment for the 17th-century Orthodox author though: Daniel has received his royal title on behalf of the Roman Pope. In excuse, Tikhon writes that the king cannot be reproached for this because “he has strengthened the Orthodox Belief and preserved it to his last day.”

Heading east

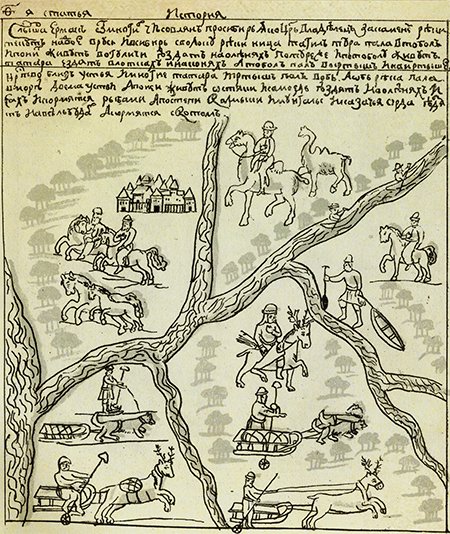

Continuing the important geopolitical topic brought up in The Latukhin Book of Degrees is the story of Russia’s advance eastward, including to Siberia.

Continuing the important geopolitical topic brought up in The Latukhin Book of Degrees is the story of Russia’s advance eastward, including to Siberia.

Dwelling on the rule of Ivan IV, archimandrite Tikhon relates the history of Kazan and Astrakhan Tatars, annexing their lands to Russia, and gives a detailed account of the main Siberian chronicle written in 1636 by Savva Yesipov, a clerk (djak) of Tobolsk archbishop, about pre-Russian Siberia, its history, geography and its annexation to Russia. In the following chapters the story of Yermak’s campaign proceeds to the account of establishing Tobolsk by governor D. Chulkov and setting up other Siberian towns, i.e. the beginning of systematic development of the trans-Urals lands. In this way, the all-Russia work integrating the main paths of national history included Russian and aboriginal Siberia.

Of great interest is the reconsideration of a few important events of Great Russia’s history under the influence of the famous Story of the Khanate of Kazan. The unknown author of The Kazan Story, Russian by origin, lived in Kazan from 1532 for twenty years as a captive turned to the Muslim faith, and only when Kazan was attacked by Russians in 1551, he left the town, returned to Orthodoxy and joined the troops of Ivan the Terrible. Long before that, he had had an opportunity to go back to Rus’ but ignored it for some reason. Some historians believe that he performed secret service at the Kazan court. Whatever the case, he managed to collect an impressive corpus of local sources narrating the Tatar history over 300 years and to offer it to Russian readers. Even though his attitude is pro-Moscow, he narrated quite a few versions and facts contradicting the account of events found in Russian chronicles and in The Book of Degrees.

Here is just one example. At the very height of the internal war for the Moscow throne that broke out in the second quarter of the 15th c. between Grand Prince Vasily II, grandson of Dmitry Donskoi, and princes of Galich of Mersk, the latter received decisive help from the Tatar khan Ulu-Mukhamed, the famed founder of the Khanate of Kazan. As a result of a Tatar raid, Vasily II was captured and blinded. Naturally, all the Russian sources written at the time of Vasily, who eventually won, and at the time of his descendants characterized negatively both the Russian enemies of the Grand Prince and their Tatar allies. The author of The Kazan Story, however, lays the blame not on the Tatar khan, in the first place, though he calls him a “wicked snake,” but on the Moscow Grand Prince and his counsel. When Ulu-Mukhamed abjectly pleaded with Vasily II not to breach the peace treaty concluded between them before and not to attack the insignificant Tatar forces under the town Belev, Vasily ignored his pleas and sent a big army against him. On that occasion, God was not on the side of the Russians, despite their tenfold superior manpower. The Kazan Story, and archimandrite Tikhon along with it, attributes this sad outcome for the Russians to the fact that Vasily II violated the oath sworn by him to the Tatar khan at the threshold of an Orthodox church and enforced by addressing the single god of Orthodox and Muslim believers: “And if I do evil to you, as you suppose, offending your love to me, when you fed me like a beggarly suppliant, let your God who is my God kill me, in Him I believe” (italicized by us – N.P.).

Here is just one example. At the very height of the internal war for the Moscow throne that broke out in the second quarter of the 15th c. between Grand Prince Vasily II, grandson of Dmitry Donskoi, and princes of Galich of Mersk, the latter received decisive help from the Tatar khan Ulu-Mukhamed, the famed founder of the Khanate of Kazan. As a result of a Tatar raid, Vasily II was captured and blinded. Naturally, all the Russian sources written at the time of Vasily, who eventually won, and at the time of his descendants characterized negatively both the Russian enemies of the Grand Prince and their Tatar allies. The author of The Kazan Story, however, lays the blame not on the Tatar khan, in the first place, though he calls him a “wicked snake,” but on the Moscow Grand Prince and his counsel. When Ulu-Mukhamed abjectly pleaded with Vasily II not to breach the peace treaty concluded between them before and not to attack the insignificant Tatar forces under the town Belev, Vasily ignored his pleas and sent a big army against him. On that occasion, God was not on the side of the Russians, despite their tenfold superior manpower. The Kazan Story, and archimandrite Tikhon along with it, attributes this sad outcome for the Russians to the fact that Vasily II violated the oath sworn by him to the Tatar khan at the threshold of an Orthodox church and enforced by addressing the single god of Orthodox and Muslim believers: “And if I do evil to you, as you suppose, offending your love to me, when you fed me like a beggarly suppliant, let your God who is my God kill me, in Him I believe” (italicized by us – N.P.).

In the years when The Latukhin Book of Degrees was written, quite a few large Muslim peoples had joined the Russian crown. Looking almost two hundred years back, archimandrite Tikhon unambiguously states, “The submission and humility of the pagan tsar overcame the power of Grand Prince for he shouldn’t have violated the oath he had administered to the pagans.”

The comprehensive corpus of national history created in 1678 by archimandrite Tikhon Makarievsky is an important development of the basic ideas laid down in the 16th-century The Book of Royal Degrees in the context of new events.

The comprehensive corpus of national history created in 1678 by archimandrite Tikhon Makarievsky is an important development of the basic ideas laid down in the 16th-century The Book of Royal Degrees in the context of new events.

The greatest strength of this work was revealing for Russian readers of the history of new territories merged in Moscovia: Ukraine, Byelorussia, the Khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan, and Siberia. They were all incorporated by the principal of the Zheltovodsk Monastery in the common historical process of establishing the State of Russia. Tikhon made a serious attempt to draw a picture of the common, since the time of Kiev Rus’, past of all the three East Slavic ethnic groups and of the ethnic groups whose common with Russia history referred to a later time.

To carry out this grandiose task, the author of The Latukhin Book of Degrees has managed to find quite a number of valuable sources such as Synopsis by Innikentiy Gizel, The Kazan Story, and The Siberian Chronicle by Savva Yesipov. Yet, having quoted a huge number of data from these sources, each of which considered the past at its own angle, he failed to accord the dissonant facts and to consistently explain their roots and consequences. Admittedly, this was not his intention. The task of giving such an explanation, of transition from accumulated historical facts to a single concept of the past of the Russian Empire will become the concern of scholars in the future centuries – and not an easy one.

ON STEPAN RAZINThe historians closely engaged in Stepan Razin’s movement pointed out the accuracy of the factual data given in the book. Its author carefully, sometimes word-by-word, goes through the sources, relating in great detail the beginning of Stepan Razin campaign, his Persian expedition, massive crossing over to his side of the inhabitants of Middle and Lower Volga regions, and the Urals. The author pays particular attention to the siege of the Makarievsky Zheltovodsky monastery, when the neighboring villages of Murashkovo and Lyskovo joined the rebels, the negotiations between the monastery authorities and the rebels, repulsing the first attacks and capture of the monastery. The atrocities committed by Stepan Razin and his Cossacks have been shown extremely realistically.

It goes without saying that these horrible scenes were not popular with Soviet historians, who nevertheless willingly used the trustworthy factual material from The Latukhin Book of Degrees concerning the progress of the “peasant war under the leadership of Stepan Razin,” and mentioning in passing its “mystic churchy character.” Indeed, similarly to the movement of Ivan Bolotnikov, Tikhon attributes massive joining Razin’s associates of the nearby and faraway population exclusively to God’s wrath, ignoring more earthly reasons for popular unrest. The only exception he makes is the Copper Riot of 1662, which he fairly connected to an aborted attempt at a monetary reform

References

Vasenko P. G. Zametki k Latuhinskoj Stepennoj knige. Otdel’nyj ottisk iz Sbornika Otdelenija russkago jazyka i literatury Imperatorskoj Akademii Nauk. SPb., 1902. T. LXXII, № 2. S. 1—89.

Karamzin N. M. Istorija Gosudarstva Rossijskago. SPb., 1892. T. 1.

Koreckij V. I. K voprosu ob istochnikah Latuhinskoj Stepennoj knigi // Letopisi i hroniki – 1973 g. M., 1974. S. 328—337.

Perepiska Ivana Groznogo s Andreem Kurbskim / Podgotovka teksta Ja. S. Lur’e i Ju. D. Rykova. L.: Nauka, 1979.

Platonov S. F. Drevnerusskie skazanija i povesti o Smutnom vremeni XVII veka kak istoricheskij istochnik. 2-e izd., SPb., 1913.

Sirenov A. V. Stepennaja kniga: istorija teksta / Otv. red. N. N. Pokrovskij. M., 2007

The author and publishers thank the personnel of Nizhny Novgorod State Oblast Universal Academic Library after V. I. Lenin, Russian State Library (Moscow), State Public Scientific and Technical Library with the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Novosibirsk), Nizhny Novgorod State Open-Air Museum of History and Architecture and Sergiev Posad State Open-Air Museum of History and Art for their kind assistance with publishing this article

The article has been prepared within the framework of the basic research programme of the Russian Academy of Sciences Presidium “Traditions and innovations in history and culture”