A True and Sad Story about Fuegia Basket and Captain Fitzroy

Once upon a time, almost two hundred years ago, on an island far far away, lost at the very end of the world there lived a little girl named Yokcushlu. The island was situated in such a nasty place — couldn’t be worse. To tell the truth, the girl had no idea about it, for she had never seen anything but the place...

The island at the world’s end

Once upon a time, almost two hundred years ago, on an island far far away, lost at the very end of the world there lived a little girl named Yokcushlu. The island was situated in such a nasty place — couldn’t be worse. To tell the truth, the girl had no idea about it, for she had never seen anything but the place.

The world’s end is a relative thing. If you take a look at a British map, you’ll find Korea and Japan somewhere in the backyard, and Great Britain right in the center of the world. But a Japanese map would tell you a different story: Japan in the middle, and Great Britain hard to find. However, no matter what map you take our girl’s home archipelago, Tierra del Fuego, is at the edge of it. Only Antarctica is further, and nobody lives there but penguins and polar explorers.

Tierra del Fuego is the name given to the archipelago by the first round-the-world traveler Ferdinand Magellan. When he was passing the islands by the future Strait of Magellan, our girl’s tribe lit fires: they must have been hoping to be finally discovered. But Magellan did not even stop to talk, slipped by the strait of his into the Pacific, and was gone in a flash.

Nobody at all wanted to stop there, so bad was this place: cold, windy, dreary… Raining snow, then snowing rain. Neither gold nor emeralds, little or no fur-animals, spices unheard of. That’s why all seafarers aimed at racing past the archipelago with all its straits and strains, strives and struggles and forgetting it forever.

You may get lucky once or twice but next time your luck may wear off and deprive you even of drowning peacefully. What if you are cast ashore? You’ll have to hang about sizzling with envy for Robinson Crusoe: no goats, no bananas, and instead of his good friend Friday nobody but malicious Fuegians. But again, in such a place even the nicest people can lose temper.

In short, everyone understood that the seafarers needed a map, but nobody was willing to draw it. To do that you’d have to spend ages in the goddamned place, measuring depths and taking coordinates of heights… The Spanish and the Portuguese, then owning the whole of South America, were generally known for their light-mindedness and did not like to sail by Tierra del Fuego, preferring to carry their loot on donkeys from coast to coast, west to east, from where it was not too far to Spain. For their light-mindedness they had to pay dearly.

In the beginning of the 19th century South America was hit by a vogue for independence, and the Spanish empire collapsed into a pile of republics. Now we know all too well what follows independence: The economy is ruined, and the independent states begin to quarrel with their neighbors. The generals from Chile and Argentina were thinking about fighting over Tierra del Fuego but then simply divided it by the meridian. They did without maps and were quite satisfied. (Speaking of dividing, they did the same with Antarctica, just in case! Up to the South Pole…)

While the generals were dividing the land they had never seen, Great Britain quietly but firmly and surely ruled the waves. The Lords of the Admiralty clearly saw that if a land can be more or less ruled without maps, waves cannot. So in May 1826, two His Majesty Ships (HMS’s), the Beagle and the Adventure, put to sea with detailed instructions as to where and what research should be done to finally draw the map.

First the ships inspected the coast of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego in the Strait of Magellan’s area, and in January 1828 the Beagle under the command of Captain Stokes went alone to investigate the west coast of the archipelago and mainland. The crew spent half a year in the gloomy country. When Captain Stokes brought his ship to Port Famine (what a jolly name!), he was too weak to shoot himself in a proper way. His shot was not exactly fortunate, and he died in the throes two weeks later.

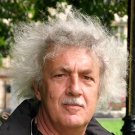

The Beagle lost her captain but not for long. In October 1828, the post was appointed to Lieutenant Robert Fitzroy who was just 23 at the moment. This year the humankind should have celebrated his 200th birthday, but it failed to do so. On July 5, 2005, I was most likely the only person to have a shot of rum in the memory of the Beagle’s Captain…

The stolen whale-boat

The ship under the command of Captain Fitzroy came back to Tierra del Fuego’s waters, and the crew went on with their research. The brave British sailors were closely watched by the tribesmen of that very girl who lived on the small island. They did so not out of sheer curiosity: they liked the whale-boat very much and decided to steal it. And, naturally, they did it at the first opportunity.

One fine morning the sailors woke up on an uninhabited island and found out that their only means of transportation had disappeared in an unknown direction. They constructed a basket out of branches, covered it with sailcloth and sent couriers to the Beagle on that jug. Way after midnight did the couriers reach the ship and report on the incident to the enraged Captain. Fitzroy immediately sent a rescue-punitive party. For 18 days following that eventful night the sailors were occupied with the search for the whale-boat.

They were searching the Fuegians’ canoes they met, intruded peaceful villages, ransacked wretched wigwams. In one of the villages they found a fallen mast; in another, a leadline. Fitzroy felt that the whale-boat was somewhere near, but nobody confessed to its whereabouts. Then he decided to take hostages and exchange them for the desired boat. Poor, naive captain, how cruelly his intentions deceived him!

From the very beginning the hostage operation went wrong. Late at night Fitzroy’s sailors surrounded the village, where the girl Yokcushlu lived. Quietly they sneaked to the dark wigwams when suddenly a dog began barking. Many years later Charles Darwin was to write in his The Origin of Species, “We see the value set on animals even by the barbarians of Tierra del Fuego, by their killing and devouring their old women, in times of death, as of less value than their dogs.” And indeed, both old and young women were sleeping but a dog began barking, and the Captain’s plan went to the dogs. The hostage operation turned to a senseless brawl. The sailors were severely beaten by stones, and one Fuegian was shot.

Fitzroy took the fact very hard and described it in the following words, “the poor man, mortally wounded, threw one more stone, fell on the shore and breathed his last.” His hard feelings did not prevent him from ordering to prepare a skeleton out of the man’s corpse for the future research. Who knows, this skeleton might very well still be in the Natural History Museum in London.

But let’s return to the failed operation. Most of the population dispersed but a few women with children. They were taken hostages and the Captain expected that the worried husbands and fathers would bring the whale-boat for exchange. But the husbands and fathers were not in a hurry. They did not value their women much and were waiting, contentedly rubbing their hands, when the Captain got tired of their wives and was ready to give up his last whale-boat just to get rid of the hostages.

But the women betrayed the expectations of both parties by running away. So the Captain was left without the whale-boat but with three small children in his care. For some time he cherished hope, then despaired and ordered to bring the children back to their tribe. But one girl liked it so much aboard the Beagle that she refused flatly to leave it. That was Yokcushlu. Fitzroy gave her a new name — Fuegia, after the name of archipelago, and the last name — Basket, honoring the island where the whale-boat was stolen. The Captain named the island after the basket which saved the sailors. He also named the straits separating the island from the neighboring ones, the Strait of Whale-boat and the Strait of the Thieves.

By this time Fuegia turned ten, and she was so nicely rounded and joyous that both the sailors and the severe Captain liked her very much. It was the latter who came to the conclusion that before they learned the local language and the locals got to know them, they would not learn anything about the savages nor about the inland, and the locals would not have a smallest chance to grow in the eyes of the British.

Fuegia began to learn English, and her progress inspired the Captain so that he decided to take more pupils. First they lured 26 year-old York Minster, a sad and sullen fellow. Then, during just another skirmish with the locals they fished out of the water 20 year-old Boat Memory. The last one, 14 year-old Jemmy Button was bought from his father for a pearl button.

The progressors

Time came to return to England, but the Captain came to like his Fuegians, especially the youngest ones — Fuegia and Jemmy. He designed a new plan: to bring them to England, teach them the language and the basics of the right religion, and then return them back so that they could carry a light of civilization to their tribes and raise them in the eyes of the enlightened world. Many years later the Strugatsky brothers, the famous Soviet science fiction writers, was to coin a name for this kind of people — the progressors.

The Captain inquired the Admiralty, and the Lords gave their evasive consent for his plan. Fitzroy brought his pupils to England. On the way the Beagle entered Montevideo, where at that moment there was a short armistice in an endless civil war. There the Fuegians were inoculated with smallpox. However, the vaccine did not help Boat Memory, who shortly after having arrived in England contracted smallpox and died. The Fuegians were put in a parochial school and according to Fitzroy’s directions were taught, first of all, English and the basics of Christianity; secondly, using simple tools, and a little bit of arable farming and gardening; and thirdly, they were introduced to instruments. Such were the priorities set by the Captain. Fuegia and Jemmy made quite a progress, whilst York Minster turned out to be absolutely hopeless.

When they learned a little bit, they were taken to a reception by the Royal couple in St. James’s Palace. The King talked to Jemmy and York about the weather, and the Queen gave Fuegia a ring, her own hat and a purse of money for a dress. The equipping of the Fuegians for their return home began. The Royal example was followed by other good parishioners. They collected for the progressors-to-be heaps of things absolutely indispensable on Tierra del Fuego like tea-sets, table-sets, embroidered tablecloths, vine glasses, butter dishes, tea-trays, dandy hats…

After long and hard negotiations Fitzroy finally got Admiralty’s consent for the new expedition and began re-equipping the Beagle and recruiting a crew. This was how Charles Darwin got aboard as a naturalist and Captain’s companion.

The HMS Beagle put to sea in her historic voyage on December 27, 1831 under the command of Captain Fitzroy with three Fuegians on board accompanied by a missionary, Mr. Matthews. The Fuegians spent a whole year on their journey home.

Return to Tierra del Fuego

On her way to Tierra del Fuego the Beagle stopped in Rio de Janeiro. Fuegia was living there, under surveillance, in Darwin’s house and by his observations was “daily increasing in every direction except height”. Darwin thought her to be “a nice, modest, reserved young girl, with a rather pleasing but sometimes sullen expression, and very quick in learning anything, especially languages. This she showed in picking up some Portuguese and Spanish, when left on shore for only a short time at Rio de Janeiro and Monte Video, and in her knowledge of English.” York Minster and Jemmy Button also impressed Darwin in a good way, “York Minster was a full-grown, short, thick, powerful man: his disposition was reserved, taciturn, morose, and when excited violently passionate; his affections were very strong towards a few friends on board; his intellect good. Jemmy Button was a universal favourite, but likewise passionate; the expression of his face at once showed his nice disposition. He was merry and often laughed, and was remarkably sympathetic with any one in pain: when the water was rough, I was often a little sea-sick, and he used to come to me and say in a plaintive voice, ‘Poor, poor fellow!’ <…> He was of a patriotic disposition; and he liked to praise his own tribe and country, in which he truly said there were ‘plenty of trees,’ and he abused all the other tribes: he stoutly declared that there was no Devil in his land. Jemmy was short, thick, and fat, but vain of his personal appearance; he used always to wear gloves, his hair was neatly cut, and he was distressed if his well-polished shoes were dirtied. He was fond of admiring himself in a looking glass.”

In December 1832, the Beagle reached Tierra del Fuego. For the first time Darwin saw the Fuegians and was struck by the encounter, he “could not have believed how wide was the difference between savage and civilized man.” Politically correct missionary Matthews noted that the Fuegians did not turn out to be worse than he had expected. Jemmy and York Minster showed a conduct not worthy of progressors: they laughed heartily at their future charges and mimicked them. “Monkeys, dirty fools, not men!” they cried in English. It was not their tribe, it was another one, their own tribe was different, they told Fitzroy. Poor Fuegia, ashamed and terrified, hid on the bottom of the whale-boat and did not look at the shore. A few days later the expedition reached the home place of Jemmy Button and met his tribe. Here Fitzroy was in for another unpleasant surprise. As it turned out, Jemmy forgot his native tongue. He tried to talk with his tribe in a mixture of English and Spanish. Darwin wrote that “it was <…> almost pitiable, to hear him speak to his wild brother in English, and then ask him in Spanish (‘no sabe?’) whether he did not understand him.” Nevertheless Fitzroy decided to found his outpost of progress there, in Jemmy’s home place. York Minster also decided to stay there. Fuegia’s opinion was not asked for. Nobody doubted that she would stay with York Minster. As Darwin noted, “York Minster was very jealous of any attention paid to her; for it was clear he determined to marry her as soon as they were settled on shore.” Some historians believe that it was the unambiguous interest of 28 year-old York for 12 year-old Fuegia that made Fitzroy reduce their stay in the stronghold of Puritanism.

The outpost of progress

For three days the party was building the progressors’ base. Everybody including Darwin were digging gardens, planting potatoes and turnip, erecting wigwams and bringing there the re-settlers’ possessions: the tea- and table-sets, embroidered tablecloths and other useful things. Jemmy’s tribe was watching the process with great interest. When the work was over, Fitzroy’s crew left the missionary and his three charges on the shore and went on a week-long voyage by the Beagle Channel. At this time the outpost of progress saw some very interesting events. This is how they were described by Darwin. “From the time of our leaving, a regular system of plunder commenced; fresh parties of the natives kept arriving: York and Jemmy lost many things, and Matthews almost everything which had not been concealed underground. Every article seemed to have been torn up and divided by the natives. Matthews described the watch he was obliged always to keep as most harassing; night and day he was surrounded by the natives, who tried to tire him out by making an incessant noise close to his head. One day an old man, whom Matthews asked to leave his wigwam, immediately returned with a large stone in his hand: another day a whole party came armed with stones and stakes, and some of the younger men and Jemmy’s brother were crying: Matthews met them with presents. Another party showed by signs that they wished to strip him naked and pluck all the hairs out of his face and body. I think we arrived just in time to save his life. <…> It was quite melancholy leaving the three Fuegians with their savage countrymen; but it was a great comfort that they had no personal fears. York, being a powerful resolute man, was pretty sure to get on well, together with his wife Fuegia. Poor Jemmy looked rather disconsolate, and would then, I have little doubt, have been glad to have returned with us. His own brother had stolen many things from him; and as he remarked, ‘What fashion call that’ he abused his countrymen, ‘all bad men, no sabe (know) nothing’ and, though I never heard him swear before, ‘damned fools.’ Our three Fuegians, though they had been only three years with civilized men, would, I am sure, have been glad to have retained their new habits; but this was obviously impossible. I fear it is more than doubtful, whether their visit will have been of any use to them.”

That’s how the ball of our Cinderella-Fuegia ended. Everything was in the past — the Queen’s reception, the carriage drives in London, the unhurried strolls with Darwin in Rio de Janeiro. Fuegia waved her hand to the Captain and stayed on the desolate shore of the cold sea. That day she was, as Fitzroy wrote down in his diary, as usual clean and neat.

Fitzroy was leaving the land heavy-hearted. The work to which he had devoted so much strength and time, into which he had put his heart and soul ended up in a shattering defeat.

The sad return

It is easy to understand Fitzroy’s disappointment, but let us imagine the following scenario. The same year 1828. Not far from the hunting estate of the Dukes of Grafton, where Robert Fitzroy spent his childhood, a flying saucer lands. Little green men come out of it, lay out their possessions and leave to see to their affairs. At this time the locals come and carry away all the things to their barns. The newcomers return and discover the loss. They begin to fly on their saucer over the nearby villages, fire their blasters and claim their things back. The locals do not understand them and hide in the bush. Then the aliens take hostages — two young men and one girl — and leave. In three years the saucer comes back and lands the former hostages, who are dressed as the aliens, speak the alien language, laugh at the locals, call them monkeys and dirty fools. The aliens provide their progressors with annihilators, disintegrators and other light-sabers, leave with them a missionary-alien and take off. Now imagine what they will see when they come back in a week’s time to the outpost of progress. Done? Then you should clearly see how lucky Jemmy Button, York Minster, Fuegia Basket and especially Matthews must have been.

Fitzroy, however, never lost hope. Yes, he failed to establish a mission, but the hope remained for “some shipwrecked sailor being protected by the descendants of Jemmy Button and his tribe!”

In a year the Beagle came back to the outpost of progress.

This is how Darwin describes the sad return. “On the 5th of March, we anchored in a cove at Woollya, but we saw not a soul there. <…> Soon a canoe, with a little flag flying, was seen approaching, with one of the men in it washing the paint off his face. This man was poor Jemmy, — now a thin, haggard savage, with long disordered hair, and naked, except a bit of blanket round his waist. We did not recognize him till he was close to us, for he was ashamed of himself, and turned his back to the ship. We had left him plump, fat, clean, and well-dressed; — I never saw so complete and grievous a change. As soon, however, as he was clothed, and the first flurry was over, things wore a good appearance. He dined with Captain Fitz Roy, and ate his dinner as tidily as formerly. He told us that he had ‘too much’ (meaning enough) to eat, that he was not cold, that his relations were very good people, and that he did not wish to go back to England. <…> Jemmy had lost all his property. He told us that York Minster had built a large canoe, and with his wife Fuegia, had several months since gone to his own country, and had taken farewell by an act of consummate villainy; he persuaded Jemmy and his mother to come with him, and then on the way deserted them by night, stealing every article of their property.

Jemmy went to sleep on shore, and in the morning returned, and remained on board till the ship got under way. <…> He returned loaded with valuable property. Every soul on board was heartily sorry to shake hands with him for the last time. <…> When Jemmy reached the shore, he lighted a signal fire, and the smoke curled up, bidding us a last and long farewell, as the ship stood on her course into the open sea.”

The epilogue

Astonishing as it is, but we happen to know what happened to Fuegia afterwards. In the comments to his The Voyage of the Beagle Darwin wrote, “Captain Sulivan, who, since his voyage in the Beagle, has been employed on the survey of the Falkland Islands, heard from a sealer in (1842?), that when in the western part of the Strait of Magellan, he was astonished by a native woman coming on board, who could talk some English. Without doubt this was Fuegia Basket. She lived <…> some days on board.”

She had had two children with York Minster before he was killed in revenge for a murder he had committed. In 1873 she showed up at the mission. She looked rather well despite of having lost almost all of her teeth. No wonder, she was over fifty, which is an extreme old age for a Fuegian. But she did not consider herself an old woman. She was accompanied by an 18 year-old husband. She recalled with warmth London, the Beagle, her school teacher’s wife, Mrs. Jenkins and, no doubt, Captain Fitzroy. She still remembered a few English words, but forgot how to sit on chair and preferred to squat.

The last time she was seen on February 19, 1883. The missionary who met her noted that she was weak and her life was nearing the end. By this time Captain Fitzroy was long dead: on April 30, 1865, he committed suicide by slashing his throat.

We don’t know how Fuegia Basket died. If we are to believe what the Fuegians told Darwin, her death might have been horrifying: “From the concurrent, but quite independent evidence of the boy taken by Mr. Low, and of Jemmy Button, it is certainly true, that when pressed in winter by hunger, they kill and devour their old women before they kill their dogs: the boy, being asked by Mr. Low why they did this, answered, “Doggies catch otters, old women no.” This boy described the manner in which they are killed by being held over smoke and thus choked; he imitated their screams as a joke. <…> Horrid as such a death by the hands of their friends and relatives must be, the fears of the old women, when hunger begins to press, are more painful to think of; we are told that they then often run away into the mountains, but that they are pursued by the men and brought back to the slaughter-house at their own firesides!”

I hate the idea that Fuegia Basket died like this. Neither the missionaries who worked with the Fuegians in the 19th century, nor the modern ethnographers found any confirmation for the stories.

The events described in this sad and true story took place a long time ago but the characters are not forgotten. In a bay not far from the former outpost of progress the town of Ushuaia has appeared with streets named after Darwin, Fitzroy and Fuegia Basket.

Fate plays strange jokes: if it had not been for Darwin sailing on board of the Beagle, not many people would remember now about the ship as well as her captain, and the bizarre life of little Fuegia… On the other hand, had it not been for the need to return Fuegia to her homeland, Fitzroy very well might not have been interested in the expedition. And Darwin would have never gone around the world and would have become just another parson quietly collecting beetles in his parish. And The Origin of Species would never have been written. And the humankind would look differently at the structure of our world… if, at the very end of the world, Fuegia Basket’s tribe had not stolen the whale-boat.

References

Darwin Charles. The Voyage of the Beagle. London: Modern Library, 2001.

Mellersch H. E. L. Fitzroy of the Beagle. New York: Mason & Lipscomb, 1968.

Keynes R. D. (Editor) The Beagle Record. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Keynes R. D. Fossils, Finches, and Fuegians: Darwin’s Adventures and Discoveries on the Beagle. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

The article is illustrated by the sketches of Conrad Martens, the staff painter of the Beagle (from Keynes, 1979) and Robert Fitzroy (from Keynes, 2003)