Appearances Are Deceptive...

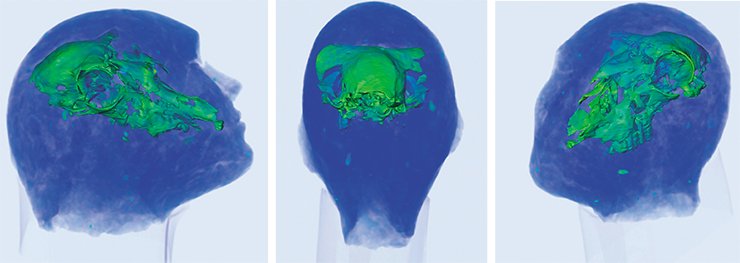

Among the exhibit-items of the Museum of the Novosibirsk Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences (SB RAS), is a sculpture of a man from an ancient burial site – a clay head with a sheep’s skull inside, detected with the help of X-ray tomography. The X-ray photograph of this unique exhibit was made on the low-dose digital X- ray facility installed at the Institute of Nuclear Physics SB RAS (Novosibirsk)

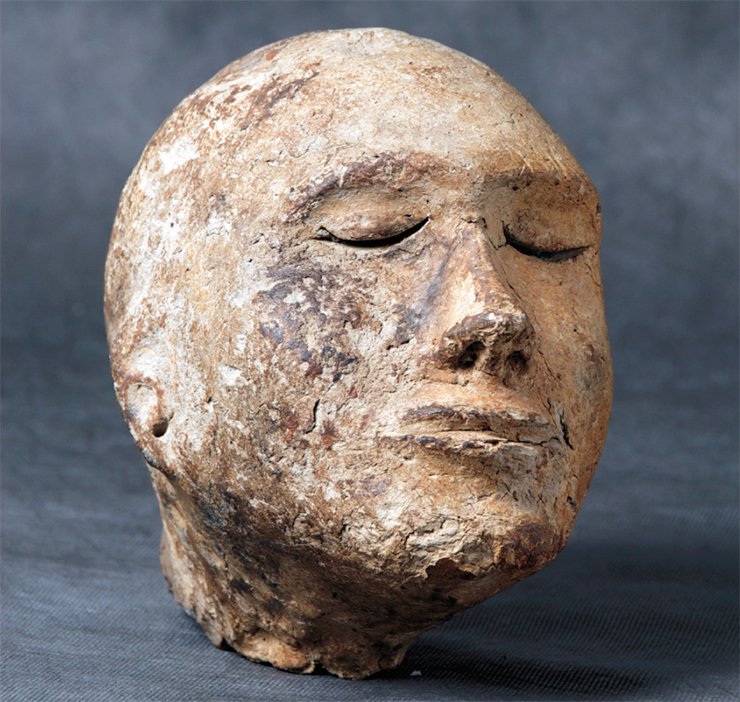

The story of this remarkable finding began in 1968. A man’s sculptured head was discovered at the Shestakov burial ground located on the right bank of the River Kiya, not far from the village of Shestakovo, Kemerovo Oblast. The burial belonging to the Tesinsk period of the Tagarsk culture is composed of ten ground kurgans, which were examined by Professor of Kemerovo State University A. I. Martynov.

In the kurgan where the head was found, inside the burial pit, there was a four-set timber blocking. On its bottom were small pieces of charred bones arranged in large assemblages. Supposedly, from 13 to 15 people were buried there. Next to the timber blocking wall, buried in a layer of red dead-burned clay, was the head, which must have been part of a burial doll of which nothing was left when the tomb was burnt (Martynov, 1974).

The very first publications dedicated to this finding noted that “inside the head, as the X-ray photograph shows, there are skull bones and a small hollow space, which, however, does not correspond to the inner size of the human skull but is much smaller” (Martynov et al., 1971, p. 168). No mention of the sheep skull was made though, and clay sculpted heads from Tesinsk burials were known to be molded on human skulls.

X-ray computer tomography develops primarily as a non-destructive testing technique. In addition, it is an efficient and sometimes the only possible way of instrumental examination of unique archaeological findings.

With a view to examining large archaeological objects, the tomograph was mounted on the Sibir low-dose digital X-ray facility designed at the Institute of Nuclear Physics SB RAS (Novosibirsk).

An X-ray apparatus with a revolving tungsten anode is used as a source of radiation. The detector is an ionization chamber with 2048 independent receivers of X-ray quanta, each 0.2 mm wide. Up to 360 projections of the object being scanned should be obtained during a session, which takes about four hours of operation time.

The tomograph makes it possible to examine samples with the sectional area of up to 300×300 mm2, with the spatial resolution of 400 microns.

The clay sculptural head of the man from the Tagarsk burial was the first archaeological finding examined by the apparatus. A ram’s skull has proved to have been used as the basis of the sculpture, as can be seen on the various projections of the object. Moreover, a detailed examination of tomographic sections allows us to trace the molding progression.

Small (up to 40×40 mm2 sectional area) objects are examined, as a rule, using a synchrotron radiation unit (VEPP-3 electron-positron facility) at the Institute of Nuclear Physics SB RAS. Synchrotron radiation is the brightest X-ray radiation, and its source generates a flow of X-ray photons whose intensity is 5 orders higher than that of a flow produced by ordinary X-ray facilities. As a result, high-quality projections of higher spatial resolution can be produced in less time.

Moreover, the prominent anthropologist V. P. Alekseev, who had examined the find, pointed to the pronounced Caucasoid type of the man’s clay face and drew the conclusion to the effect that “when the head was being made, the artist’s creativity, which usually hampers the anthropological interpretation of portrayals, must have been restricted as the portrait was evidently made after the skull” (only the latter statement has proved to be right).

What’s under the clay?

The clay heads of Tesinsk mummies always used to contain human skulls. However, as proved by anthropologists, they did not correspond at all to the features of the sculpted heads. These clay sculptures were not portraits. Neither resemblance nor the face itself was of any interest to the tribesmen performing the burial ceremonies.

The clay portraits could be used to identify specific people only because they had special coloring that must have been put on the face while the models were still alive. It was the coloring that was a sort of “passport,” which helped to establish to what family, clan, and tribe the person belonged.

The evidence for this tradition is the numerous mummies preserved in the sands of Tarim (Xinjiang, China). For example, the colorings on the faces of men and women from the Cherchen and Subashi burials look very much like these of the clay masks from the Tagarsk and Tashtyk crypts at the Minusinsk Hollow.

Hence, the fact that the features of the clay head do not match the skull hidden inside it was common for that epoch and culture. But the strange thing is that it was an animal’s skull...

A ram as a symbol

What does the sheep’s skull hidden under the clay covers depicting a man’s face tell us? What is it, an accident? Or was the animal the main hero of ancient history?

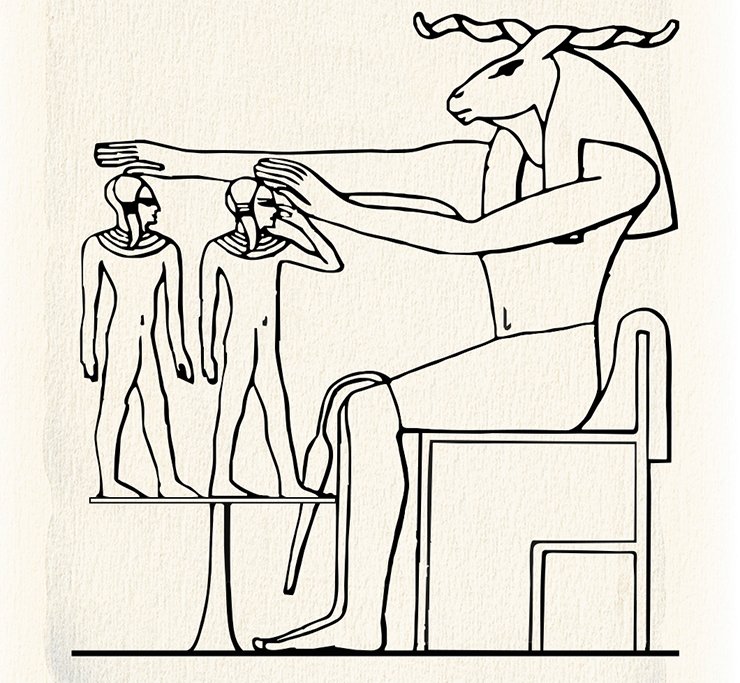

The latter hypothesis seems justified. A ram (sheep) is among the most worshipped animals of old times. Initially, the Egyptian god Khnum was depicted as a ram (later, as a man with the head of a ram).

Khnum made deities and people from clay. One of the addresses to the god had the following words: “You’ve made people on the potter’s wheel. You’ve created gods. Small and great cattle. Every day you shape everything on your wheel...” (Beliayev, 1998, p. 24).

It was believed that Khum could affect people’ destiny. He was considered to have created not only man but also his spiritual double, the Ka.

Later, Amun – the sun god, whose sacred animal was a ram – was identified with Khnum. Amun himself was often depicted as a ram or with the head of a ram. Deification of the pharaoh, worshipped as god’s son in flesh, was also connected with Amun.

When Alexander of Macedon was declared the pharaoh, priests at the oasis of Siwa, where the cult of the sun god had flourished since 7th c. BC, recognized Alexander’s divine origin from Amun. This explains the helmet with ram’s horns on the great warrior’s head, in which he was depicted on the coins of the time.

On the other hand, a ram was not the least important character in the traditional beliefs of other peoples. For instance, the Iranian-speaking Scythian-Sarmat communities had the cult of hvarnah, a special deity incarnating glory, grandeur, might, happy destiny, luck, richness, and power. Its zoomorphic image and symbol is a big and strong ram.

The Tagarsk people were engaged in both stock-raising and agriculture. By their physical type they were Caucasians similar to the Scythians of the Black Sea region.

The Tagarsk culture was widespread in Minusinsk Hollow and in the eastern part of the Kemerovo Oblast; a special area of Tagarsk culture is a patch of forest steppe along the Yenisei near the city of Krasnoyarsk. The name “Tagarsk” derives from the kurgans situated near the island of Tagarsky on the Yenisei and Lake Tagarskoye to the south of Minusinsk, which were excavated in the second half of the 19th c. by A. V. Andrianov.

The early-Tagarsk kurgans are low earth mounds with vertically sunk stones. On the kurgans are hedges made of massive stone plates with one to six graves inside, and one or two people buried in them.

From the 5th c. BC the burial ritual changed. The mounds became larger: up to 40 meters or more in diameter. Most often, under a mound, a single big burial pit intended for many dead bodies was located: a grave was found in which a hundred people were buried. Huge kurgans intended for kings appeared. The best-known of them is Salbyk, located 60 km from Abakan – it was 30 meters high.

The Tesinsk stage was the final period of the Tagarsk culture and transition to the succeeding Tashtyk epoch (2nd and 1st cc. BC). This stage got its name from the first monument, the Bolshoi Tesinsk kurgan, examined in 1889 by the Finnish expedition of I. R. Aspelin.

Typical for the Tesinsk period are huge single kurgans with earth mounds and massive stone walls in their foundation, as well as earthen burial grounds consisting of many separate graves (from 8 to 100 and more). The Tesinsk crypts are supposed to be clan or family tombs, where 16 to 200 people used to be buried.

It was in the Tesinsk crypts that clayed trepanned skulls of the buried were first found. On their faces, the clay heads had patterns in red paint depicting a tattoo or coloring, according to some researchers. Soft issues had been removed from the dead bodies; the bones had been banded together with twigs, wrapped with grass bunches, and sewn round with thick leather – the result was a burial doll.

The crypts were usually committed to the flames. The origin of the ritual burning of the burial chamber and the reasons behind this practice are unknown

A ram as a symbol of hvarnah was widely spread in the Sassanid Iran beginning with Shapur II, who ruled from 309 to 379. The king himself wore a gilded helmet shaped as a ram’s head. It is wearing such a helmet, which embodies the king’s hvarnah, that Prince Varakhran was depicted on the silver dish dated by the late 4th or early 5th c.

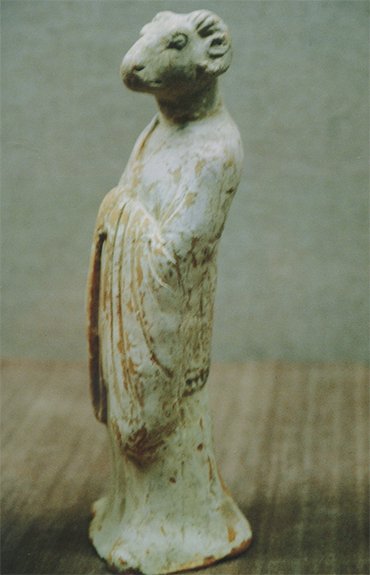

Similar ideas about a ram’s divine essence are still in place with a few peoples of Central Asia. A ram has been used in all critical rituals as the animal that possesses hvarnah and as a man’s double.

To illustrate, Pamir Tajiks performed a ritual of making a ram look like a human. The face of the animal, brought as sacrifice on the occasion of house-warming, was made up: its eyes, eyelashes, and eyebrows were painted with surma. A line was drawn on the nose, from eyebrows to the upper lip, which made the ram’s face resemble a human face; a turban of white fabric was attached to the head. In this disguise, the ram personified a man during the ritual.

A similar rite is performed by the Yazgumelts: at a traditional festival, the scene of a human sacrifice is played, in which the man is replaced by a ram. The head of the sacrificed ram was tied with a white cloth, with eyes drawn on it to make it look like a human face. The ram was then thrown down through the smoke flap on the roof and slaughtered.

The Cis-Pamir Tajiks have a fairy tale relating that when a false burial of a man was performed, the corpse of a sheep was put into the grave.

A human’s replacement

Now let us go back to our find. So in a burial crypt of Tagarsk culture, together with people, a sheep in human disguise was buried. As this is the only such case so far, any explanations of this phenomenon will undoubtedly contain, alongside the elements of uniqueness, elements of chance.

Now let us go back to our find. So in a burial crypt of Tagarsk culture, together with people, a sheep in human disguise was buried. As this is the only such case so far, any explanations of this phenomenon will undoubtedly contain, alongside the elements of uniqueness, elements of chance.

The Tesinsk people may have buried in this extraordinary manner a man whose body had not been found (the man could have got lost in the taiga, drowned, or disappeared in alien lands). The man was thus replaced with his double – the animal in which his soul was embodied. This must have been the only way to ensure the after-death life of a person who had not returned home.

Archaeologists know a number of such burials, referred to as cenotaphs, which have no human remains but may contain a symbolic replacement. As the latter, an animal could have been used.

Another hypothesis as to why a false burial was performed could be giving the man a chance to have a fresh start, a new life in a new status. Instead of a living man whose death was staged for some reasons, an animal – a sheep in human disguise – was offered.

This ancient clay portrait, whose mystery we have been trying to solve, is very much in line with the bygone epoch and culture and, today, does not appear to be extraordinary.

A modern person can be struck by the snapshots made with the help of modern technologies – they look weird, irrational... These amazing pictures show paradoxical combinations of shapes, compatibility of the incompatible.

Without suspecting it, the ancient sculptor created a surrealistic work of art whose beauty and secret meaning have been discovered only now, two thousand years later.

What does this mysteriously smiling, remarkable face pregnant with an animal substance tell us? Maybe those appearances are deceptive and we are not entirely human...

References

Alekseev V. P. Anthropological characteristics of the sculpted portrait from the Shestakov burial // SА (Soviet Archaeology). 1974.# 4. P. 242—244.

Beliayev Yu. Ancient animals-gods. Mythological encyclopedia. M.: Kniga i biznes, 1998.

Kuzmin N. Yu., Varlamov O. B. Peculiarities of the burial rite performed by the Minusinsk Hollow tribes at the turn of the era: experience of reconstruction // Metodicheskiye problemy arkheologii Sibiri. Novosibirsk, 1988.

Litvinsky B. A. Semantics of ancient Pamir beliefs and rites (1) // Central Asia and its neighbors in ancient times and in Middle Ages. М.: Nauka, 1981. P. 90—122.

Martynov A. I. A man’s sculptural portrait from the Shestakiv burial // SА. 1974. # 4. P. 231—242.

Mukhiddinov I. Home-related rites and rituals of Pamir Tajiks. Late 19th and early 20th c. (Materials for the Historical-Ethnographic Atlas of the peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan) // SE (Soviet Ethnography). 1982. #2. P. 76—83.

Monogarova L. F. Materials on Yazgulemts ethnography // Central Asian ethnographic collection, TIE New series. V. XLVII. М.: AN SSSR, 1959.

Pshenitsina M. N. The Tesinsk stage // The steppe zone of the USSR Asian part in the Scythian-Sarmat times. М.: Nauka, 1992.

Drawings by Ye. Shumakova (Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography SB RAS, Novosibirsk)