Biblical Czars of the Khanty Sanctuary

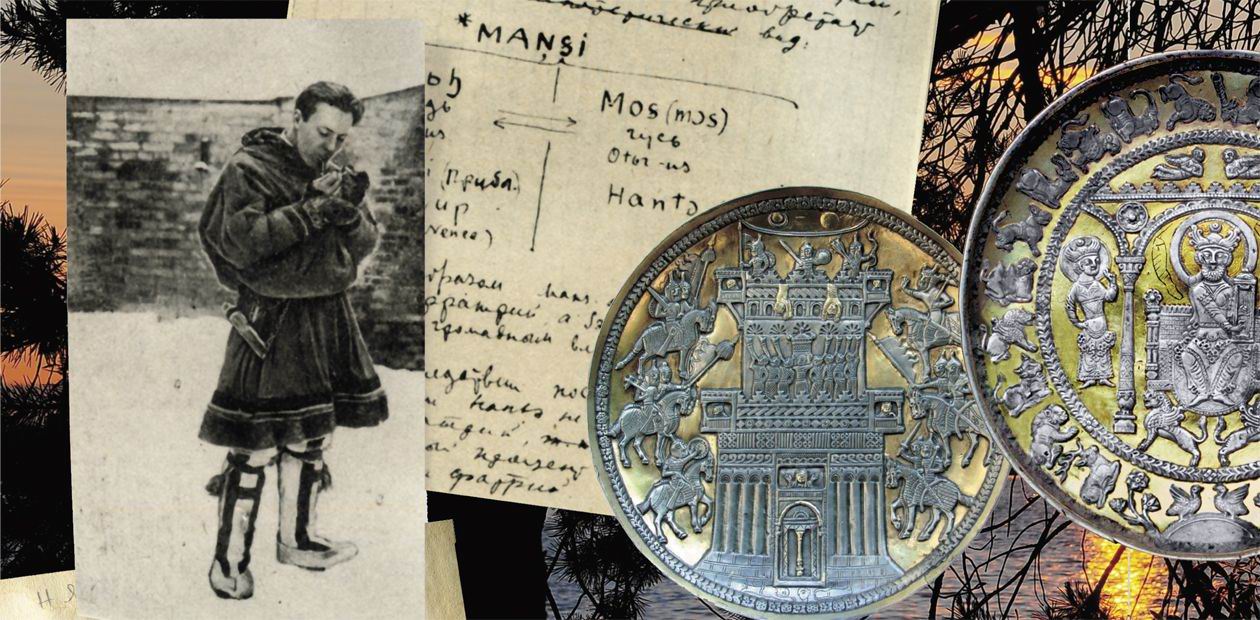

In 938, during an expedition to the Urals and upper reaches of the River Lozva, the prominent scholar of ancient Siberian cultures V. N. Chernetsov wrote down a legend about a silver dish that local fishermen pulled out of the waters of the Ob and later delivered to a Mansi sanctuary. As luck would have it, in 1985 I. N. Gemuev and the author of the present article happened to discover the dish: it was a major fetish of a cult site located not far from the town of Verhne-Nildino on the North Sosva River. The Nildin dish turned out to be a twin of the Anikov dish found in 1909 in the Upper Kama region and now kept at the Hermitage.

Interestingly, the first version of the legend written down by V. N. Chernetsov says that there were "seven dishes, all identical" in the fishing net. The researchers have an information about two more "dishes with images" kept at the North Sosva settlements , but regrettably, they have not been located by specialists yet.

The search continued. During the trips to the Khanty and Mansi settlements in the Lower Ob region, the author always showed the picture of the Nildin dish to local inhabitants, dreaming of a miracle. In 1999 an old Khanty man looking on the photo suddenly brightened up and said that the local sanctuary had a similar, in his words, "Byzantine" dish…

In 1938, during an expedition to the Urals and upper reaches of the River Lozva, the prominent scholar of ancient Siberian cultures V. N. Chernetsov wrote down a legend about a silver dish that local fishermen pulled out of the waters of the Ob and later delivered to a Mansi sanctuary. As luck would have it, in 1985 I. N. Gemuev and the author of the present article happened to discover the dish: it was a major fetish of a cult site located not far from the town of Verhne-Nildino on the North Sosva River. The Nildin dish turned out to be a twin of the Anikov dish found in 1909 in the Upper Kama region and now kept at the Hermitage*.

Interestingly, the first version of the legend written down by V. N. Chernetsov says that there were “seven dishes, all identical” in the fishing net. On the one hand, the Anikov dish could have come from the same net as the recording clearly said that “all the other dishes were taken to different places”; on the other hand, the words “all identical” should not be interpreted literally, i. e., with the same plots depicted on them. The size, shape, or other external characteristics of the dish could have been meant.

According to V. N. Chernetsov, in the 1930s another “silver dish depicting seven people” was in the settlement of Yany-Paul on the North Sosva. In 1997 they told me about a “shaman place” in the upper reaches of the River Yalbynia (the left tributary of the North Sosva). Next to the cult barn three stones were put up, which held a large silver dish, darkened with time, showing four riders. Regrettably, the two latter dishes have not been located by specialists yet.

The search continued. During my trips to the Khanty and Mansi settlements in the Lower Ob region, I always showed the picture of the Nildin dish to local inhabitants, dreaming of a miracle. In 1999 an old Khanty man looking on the photo suddenly brightened up and said that the local sanctuary had a similar, in his words, “Byzantine” dish.

Visit to the “Dog God”

Getting to the sanctuary turned out to be not easy, even though we could see it from the Ob bank; the most difficult thing was to talk the hosts into letting a stranger step onto the sacred area. The talks continued throughout the evening deep into the night. Needless to say, I was upset.

AT THE KHANTY SANCTUARY

Inside the barn, next to the far wall is a big chest, in which the figure of the main spirit living here, Kurt-aki, is kept. His head is made from a single piece of wood and covered with a gold lace. The hair is made from a fox or dog skin. They addressed the spirit at difficult times, promising to thank him for his help. The promise must be kept; otherwise, some disease or evil will befall the person. Also, Kurt-aki is known as “dogs’ god”, his zoomorphic guise is a dog or a red fox. A common gift offered to the spirit is lead figures of dogs, in different sizes.Standing on the chest are the figures of five patron spirits: four of them are sabers with scarves tied to their grips, and the fifth – Ink-vert-poh – is a set of arrows wrapped in shreds of fabric. He is made offerings to save people from drowning.

Three meters to the left of the shred a few osier-bed trees are growing. Between the shred and the trees they install a pole on which sabers, sacrificial scarves, and skins are hung.

I have attended the ceremony of treating spirits twice. Four brothers were present; the keeper of the sanctuary was the youngest, Alexander. First, a fire was made from the wood gathered beforehand and stacked under the trees. From the shred (in which the sacred chests are kept) standing behind the living house, Alexander brought clean boots with a 20-kopeck coin sewn on top of each of them, drew a circle with them “cum sole” above the fire (to “purify” them), and warmed his hands over the fire three times. Then, he lit a shelf fungus and smoked the barn door, opened it, and put the smoking shelf fungus inside. In the meanwhile, they began cooking a fish soup and tea over the fire.

Alexander put on the clean boots and climbed up into the barn (ritually, the sabers are brought out first; the first one is brought out and put back only by the sanctuary’s keeper while the other sabers can be approached by one of the brothers), carried out a saber, grip forward, and hung it on the one side of the pole. To counterweight the saber, many scarves were fixed to the other side of the pole. After that, he handed over the other sabers, grips forward, to his older brother, and the brother put them on the pole to the right of the first saber. The saber grips were wrapped in fabric flaps and the blades were bare.

Ink-vert-poh (a bunch of arrows) was carried out next and put, points up, under the osier-bed trees, right underneath the pole. The last to come out was the forth saber, which was also hung onto the pole, and to the right of the sabers two fox and one badger skins were hoisted. Underneath the hanging sabers, a board was put on the ground. A cup with smoked fish and, later, a plate of fish soup and a bottle of vodka were put on the board. Another cup with smoked fish and a bottle of vodka were taken by the master into the barn.

In front of the barn, three boards were put: two “chairs” and a “table” between them, on which treatment for the participants was arranged: fish, bread, and vodka. The men faced the barn, bowed their heads three times, and turned around “cum sole”. Then they had a meal, during which the plates with fish and vodka were put on the barn steps in order to treat the spirits.

When the meal was over, all the ritual items were returned to the barn in the reverse order. Before that, everybody in turn kissed the blade of each saber three times, and then the bunch of arrows. The pole and boards were put pack, and the barn door was closed. Again, the men bowed their heads and turned “cum sole”.

A person who came there for the first time had to throw a coin inside the barn. According to informants, shamans with axes would often go there to practice witchcraft: some of them did it in silence, others singing. To offer sacrifice, hens used to be brought; in the winter, they would kill a deer.

The next morning, however, we were standing in front of the barn together with the hosts – four brothers. We turned three times “cum sole”, put a glass of vodka and a plate of whitefish to the god, and asked him not to be angry with us for this untimely visit. The keeper of the sanctuary withdrew four sabers signifying patron spirits; they were mounted on a big chest that held a figurine of the local god and were propped against the back wall. After that, the keeper took out from the chest the dish wrapped in a red scarf. During the ritual, pieces of sacrificial bread are put on it, these can be taken only by elders or guests-orphans.

“Seven dishes, and all identical”… I was into luck: I have held in my hands both the Nildin dish and the dish from the Khanty sanctuary on the Malaya Ob. Indeed, they looked identical in shape, diameter, weight, metal, and production method – this became evident at first sight.

Sacred “Byzantine” plate

The dish happened to be large and heavy: 24 centimeters in diameter and weighing 1 kilogram. It was a silver cast, with gilded background of the figures.

We should remember that artifacts of this nature made it to the North as early as in the 7th—8th centuries: merchants from Central Asia would exchange them for fur, seal tusks, and even hunting birds. Strange as it may seem, dishes made in Iran, Choresm, and Sogd have mainly survived in the Urals as part of the so-called treasure-troves whereas in the East silver was melted back into metallic currency at the time of Arab conquests, takeovers and revolutionary upheavals. As a result, the lion’s share of oriental metal is now kept in the Hermitage; a few pieces are exposed in Louvre, the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum, and some others.

Circumferentially, 20 animal figures are depicted; below are two birds, with their wings up, standing at the edge of land. The depictions of animals include both real species (elk, lion, camel, mountain goat, hare, elephant, sheep, red deer, and markhor) and imaginary characters like the three winged predators.

The central scene is set in a palace hall. Underneath an arc is a throne resting on the heads of two winged lions. Sitting on the throne is a king in a big crown with wings; to the left of him there is a musical instrument resembling a cithara.

In the left (from the viewer) embrasure, a man is depicted with his right hand held down on the hip and his left hand, two fingers joined together, raised up. His winged crown has a crescent and a ball on top, similarly to the king’s crown.

The right embrasure shows a woman wearing a crown. In the upper segment of the central part are two soaring angels.

All kings shall fall down before Him…

In our opinion, the dish face depicts a scene connected with the legendary rulers of the Kingdom of Israel and Judah, David and Solomon.

The figure sitting on the throne must be David (10th c. BC), an Old Testament hero with whom subsequent Judaic and Christian traditions connected their aspirations to the Messiah: according to the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus is David’s direct descendant [1:20—21]. On the dish, he is shown as a venerable old man, which agrees with the biblical text: “…David was thirty when he was anointed king; he remained king for forty years” [2 Kings 5:4].

One of the most convincing arguments in favor of David is that the king is depicted with a musical instrument in his hands. According to the Bible, David was famed for composing and performing psalms on an “eight-stringed harp” [Psalms 6] or on “stringed instruments” [Psalms 55]. In medieval art, David often appears as a musician with a musical instrument (as a rule, a harp) in his hands. Textbook examples are David’s depictions on the reliefs of the Church of the Intercession of the Holy Virgin on the Nerl, Dmitriev cathedral in Vladimir, and the Church of Nativity of the Blessed Virgin in Bogolubovo.

Depiction of David playing among animals and birds traces to the ancient image of Orpheus overlaid with the early Christian image of the Good Shepherd.

To the right of David is Solomon, the third king of the Kingdom of Israel and Judah (c. 965–928 BC), who is described in the old Testament Books as the greatest sage. The dish shows him as a young man but David’s crowned heir: “So when David was old and full of days, he made his son Solomon king over Israel” [1 Chronicles, 23].

It appears evident that, in line with the idea of the author (or work-giver) of the dish, David is performing the psalm about Solomon, predicting him a powerful rule:

He shall have dominion also from sea to sea

And from the River to the ends of the earth.

Those who dwell in the wilderness will bow before Him,

And His enemies will lick the dust.

The kings of Tarshish and of the isles

Will bring presents;

The kings of Sheba and Seba

Will offer gifts.

Yes, all kings shall fall down before Him;

All nations shall serve Him. [Psalms 72 (71): 8–11]

Depictions of angels are not for nothing either. David’s well-known song of praise Safety of Abiding in the Presence of God may be interpreted here as the father’s address to his heir:

For He shall give His angels charge over you,

To keep you in all your ways.

They shall bear you up in their hands,

Lest you dash your foot against a stone.

You shall tread upon the lion and the cobra,

The young lion and the serpent

you shall trample under foot. [Psalms 91 (90):11—13]

Note that Solomon is depicted with his left hand lifted up and two fingers held apart from the others. He is not making the sign of a cross or giving a blessing; this was a way to depict a man speaking. Hands of sacred figures positioned in a specific manner were not looked upon as giving blessing until the 11th century and they were not interpreted as hands held for prayer until mid-15th century. “The prophets depicted in icons (prior to this time) with their hands held up or outstretched are not giving blessing or praying, they are prophesying; i.e. positioned hands signify that the person is making a prediction” (Golubinskiy, 1905). Solomon’s gesture, on the one hand, emphasizes his importance as a prophet, and, on the other hand, presents him as speaking.

The woman depicted in the palace must be Bathsheba, David’s beloved wife and mother to Solomon. She played a major part in Solomon’s official elevation when David was still alive.

Depiction of animal figures on the dish can be an illustration to the one of the best-known Psalms performed by David, Psalm 150 “Let All Things Praise the Lord”:

…Praise Him with the lute and harp!

…Praise Him with stringed instruments and flutes!

…Let everything that has breath praise the Lord. [Psalms 150: 3–6].

On the other hand, animal figures could have been connected with Solomon, who (according to Apocrypha) knew the language of all the animals.

Messengers from Ancient East

The silver dish discovered at the Khanty sanctuary was cast in Central Asia in 8th—9th cc. It is unique in terms of the plot whilst its main dimensions, method of production, and technique of ornament application relate it to the Anikov and Nildin dishes, as it was mentioned above.

The dish is most similar to products made in eastern Iran and Central Asia in 6th—9th cc., though the artist used some traditions of the earlier (Sassanid) epoch. The main idea of the then canon was to manifest the magnificence of deified authority and develop the ideal “king of kings” (including the throne scene with participation of family members). The reason for the unification of plots, iconography, and styles was cultural exchange along the Great Silk Road, which crossed Central Asia.

Underlying the plot of the dish from the Malaya Ob are important episodes of the Old Testament. This is why it is an exceptionally rare artifact referring to the Early Christian period in Central Asia.

Nestorians’ migration to the east was triggered by the condemnation of Nestorius, Archbishop of Constantinople, at the Third Ecumenical Council in 431. His views were supported in Syria and influenced the Persian Christian Church. In 499 Nestorianism was recognized formally among Persian Christians. Sassanid kings and later, Arab rulers granted protection to Iran’s Nestorian communities. By early 6th century, a Nestorian Christian community headed by a bishop was founded in Samarkand. King of Turkomen and ruler of Semirechye (“Region of Seven Rivers”, south-eastern part of modern Kazakhstan) Arslan Il-Turgyuk (766–840) made a request to Patriarch Timothy asking him to send a Nestorian metropolitan “to the country”. In Choresm, Christian colonies survived until the 7th—8th centuries.

Numerous signs in favor of the existence of Christian communities in Central Asia have weak material support. The Christian monuments are not many: at best, these are ruins of temples, crosses and rare inscriptions. As compared with these, the Malaya Ob dish is unique. The Old Testament plot and its main characters were represented in the Sassanid tradition, in the interior of the early medieval Central Asian architecture. David is naturally shown in line with the Iranian “king of kings” canon since at the time the dish was produced it was this quality of his that was emphasized by legends.

Hypothetically, a set of dishes with biblical plots was cast in Central Asia; they were intended for Christian missionaries setting off together with a trade caravan to Siberia. Evidence in support of this hypothesis is the two silver dishes mentioned earlier, the Anikov and the Nildin, with scenes from the Book of Joshua. On the other hand, the dish depicting David and Solomon could have been cast in honor of a solemn occasion, for instance, enthronement of a Central Asian king who had Christian roots.

Numi-Torum, Creator of the Universe

The enigma is why this artifact belonging to a totally different culture blended in with the Khanty ritual practices? Most likely, this happened because the plot of the dish was read in the light of local mythological beliefs.

In the center of the dish are three figures. Mythology of the Ob Ugric peoples has three most important characters who are related to one another and are often mentioned together: the supreme god Numi-Torum, his wife Kaltas, and their younger son (heir to his father’s cause on the Earth) Mir-susne-khum. Location of the figures of David, Bathsheba, and Solomon corresponded to the Mansi’s ideas of their own gods.

The plot shown in the lower part of the dish could also have been understandable for the Ob Ugric peoples. One can see two birds sitting on a semicircular hillock. In the late 19th—early 20th century the Ob Ugric peoples had a few written sacred legends about the creation of the Earth. According to the main nebular myth, a diver (or two birds) sent by Numi-Torum lifted a lump of mud from the ocean floor; it gradually grew into a small hillock, and only on the third (tenth, etc) day it became the Earth. Interestingly, one of the myth variants goes that the mud was supplied by iron birds.

We can thus suppose that the figures depicted on the dish were originally interpreted on the basis of the legend on the origin of the Earth. In the center is the Lightsome Husband-Father Numi-Torum, creator of the Universe, his wife (Kaltas) and their bogatyr son Mir-susne-khum. Below are two divers on a hillock of mud, which they have raised from the bottom of the ocean. Numi-Torum sitting on the throne is creating the Earth, bringing to life different animals. Images of many animals were obscure to the ancestors of modern Khanty and Mansi, so they added their own images like the wolf and, probably, the elk.

Regrettably, the year in which I visited the sanctuary, its keeper, a well-known shaman, was severely ill, he died right after the New Year. He took with him to the grave stories about the history of the dish, which explained the Khanty view on the semantics of the figures depicted. The new keeper and his brothers had heard about these stories but were not able to reproduce them. They could only remember that the king with a head of voluminous hair sitting on the throne was interpreted in the local tradition as the greatest local god, long-haired Tek-iki.

Though interpretation of the plot has been lost, the silver dish is a remarkable monument of Ancient East, which has been kept for over a thousand years as a sacred attribute of the Khanty sanctuary.

References:

Baulo A. V. Silver Plate from the Malaya Ob // Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia. – 2000. – № 4. – P. 143—153.

The Bible. Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments. – Brussels, 1973. – 2358 p.

Gemuyev I. N. Another Silver Dish from the Northern Cis-Ob Region // Izv. SО АN SSSR, ser. istorii, filologii i filosofii. – Novosibirsk, 1988. – # 3. – Issue 1. – P. 39—8.

Golubinskiy Ye. On our Polemics with Old-Believers. Moscow: B.i., 1905. – 260 p.

Darkevich V. P. Artistic Metal of the East. – Moscow; Leningrad: Nauka, 1976. – 198 p.

Chernetsov V. N. On the Penetration of Oriental Silver to the Cis-Ob Region // TIE, n.s. – 1947. – Vol. 1. – P. 113—134.

Marschak B. I. Silberschätze des Orients. Metallkunst des 3. – 13. Jahrhunderts und ihre Kontinuität. – Leipzig: VEB E.A. Seemann Verlag, 1986. – 438 S.

* The Legendary Nildin Dish by А. V. Baulo, SCIENCE First Hand, № 2(26), 2009 Russian print edition, and # 1(22), 2009 electronic English version