History Embroidered in Wool

When fabrics are unearthed from a snow-powdered burial pit of a nomadic tribe head, what you least expect to see on them is bunches of grapes and pomegranates. Did the cattle raisers roaming the Mongolian steppes had any idea at all of the patterns shown on the woolen towel put, among other valuable offerings, into the grave of a high-placed person? Felt, fur, leather, kumis, meat, wild-growing herbs, worshiping the Sky, the Sun and the Moon – this is what the nomads’ life is about. Where does this exquisite fabric come from and what kind of history is embroidered on it?

The very first explorations of the Noin-Ula Xiongnu burial kurgan (tumulus) in North Mongolia, conducted in 1924—1925 by an expedition of the famous traveler P. K. Kozlov, produced surprising results. Among the most amazing were fragments of embroidered woolen draping carpets, now kept at the Hermitage (St Petersburg, Russia). Evidently, these fabrics bore no reference to the nomadic culture in the burials of whose representatives they had been discovered; and yet the judgments on the origin of the textile were diverse.

Some scholars considered them Greek or Geek-Baltic (Trever, 1940; Borovko, 1925) whereas the well-known Russian archaeologist S. I. Rudenko supposed that they “were produced by overseas craftsmen – Bactrian and Parthian – located with the Xiongnu headquarters” (1962, p. 108). Р. Grishman (1962) saw on the textile fragment from the 25th kurgan a Parthian’s head, and G. A. Pugachenkova thought the depiction resembled the Bactrian king Gerai. However, with respect to the embroidered fabric from the 6th kurgan, she noted that “neither the men’s attire or headgear, nor their horses’ harness have analogues in Bactrian art, whereas, judging from the border decoration, the fabric must have been made in one of the Greece-influenced centers of Middle East, possibly adjacent to Bactria” (ibid, p. 173).

As a result, modern literature refers to all the embroidery as “Bactrian”, without giving any reasons (Yelikhina, 2010). Fragments of similar embroidered drapery in the 20th and 31st Noin-Ula kurgans, discovered in 2006 and 2009 by the Russian-Mongolian expedition, take us back to the issue of the origin of these unique artifacts and plots depicted on them.

Carpet “painting”

Let us note at once that all the embroidered drapery carpets from the Noin-Ula kurgans (including these discovered recently) were produced in the same place and at the same time. Their indisputable affinity was marked as far back as in 1962 by S. I. Rudenko, who was the first to publish materials on the Noin-Ula kurgans.

All the carpets were produced in the same way: the embroidery was made on long woolen widths, sewn from several pieces of the same cloth, joint in a particular way. The warp cloths alternated with the weft cloths, which made the artifact more lasting (as found by Doctor of History T. N. Glushkova). Sewn on to the upper and lower end of the carpets were borders of wide striped ribbon, decorated with embroidery. Attached below was an unadorned width of coarse textile, probably for a specific purpose (the Kazakh bed carpets were made in a similar way, with their lower, unadorned end intended for bedding).

Herodotus wrote that the Persians made important decisions only in a state of intoxication: “Drinking wine, they usually discuss the most important matters” (book 1, 133). And yet, there is good reason to believe that the scene demonstrates a ritual libation of haoma, bestowing “comprehensive knowledge” on its intoxicated participants, as the Zoroastrians’ sacred book, Avesta, says.

Compositionally and in many other aspects, the embroidery is modeled on the Achaemenid works of art and belongs entirely to Iranian culture. Basing on the combination of characteristic persons, realities (such as costume, weapons, tableware, the chair, and ornaments), and the date of the tumuli in which the textile in question and similar fabrics were found (last years of 1st c. BC to first decades of the 1st c. AD), it can be supposed that the events embroidered on the carpet from the Xiongnu burial mound reflect scenes from the life of Indo-Scythian dynasties or succeeding Indo-Parthian dynasties, demonstrating their adherence to a variety of Zoroastrian belief

The support fabric of Noin-Ula carpets also proved to be similar – soft, fine, even, canvas-structured, looking like woven rib fabric, it must have been meant originally for clothing. Not complicated to produce but of good quality, it testifies to a high level of handicraft.

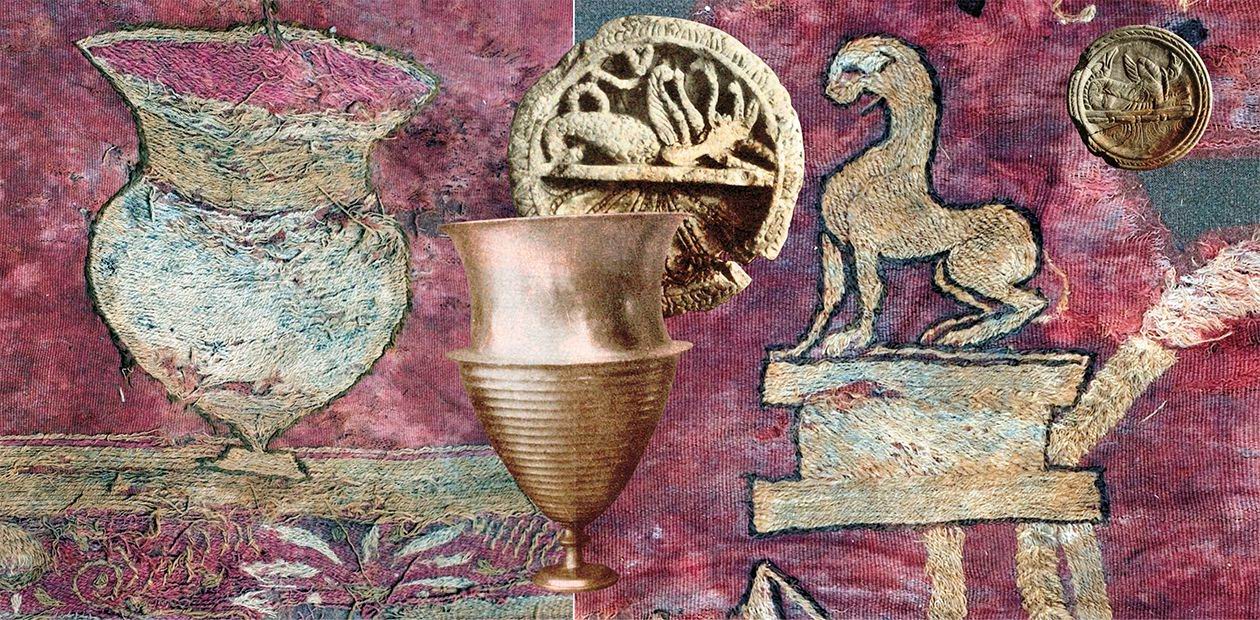

The embroidery technique should be dwelt on separately. “Characteristic for embroidered drapery carpets is overlaying the cloth with loosely twisted threads of various colors and attaching them on the cloth’s surface with exceptionally fine threads” (Rudenko, 1962, p. 105). This embroidery technique is typical for heavy gold needlework, found in burials since as early as the 1st c. BC on the territory of Central Russia, West Siberia, the Pamirs, and Afghanistan (Yelkina, 1986; Matiushchenko, Таtaurova, 1997; Sarianidi, 1989; et al.). The woven gold thread was overlaid by the pattern and attached by another yarn, maybe silk thread. The pinpoint accuracy was achieved through outlining the pattern elements with a gold contour. This technique was discovered when gold needlework fragments from the burial of a distinguished Sarmatian woman located in Soklova Mogila, Astrakhan oblast, were studied (Yelkina, 1986). It was this technique that was applied by the Noin-Ula embroiderers, with woolen thread used as the outline.

The embroidery technique should be dwelt on separately. “Characteristic for embroidered drapery carpets is overlaying the cloth with loosely twisted threads of various colors and attaching them on the cloth’s surface with exceptionally fine threads” (Rudenko, 1962, p. 105). This embroidery technique is typical for heavy gold needlework, found in burials since as early as the 1st c. BC on the territory of Central Russia, West Siberia, the Pamirs, and Afghanistan (Yelkina, 1986; Matiushchenko, Таtaurova, 1997; Sarianidi, 1989; et al.). The woven gold thread was overlaid by the pattern and attached by another yarn, maybe silk thread. The pinpoint accuracy was achieved through outlining the pattern elements with a gold contour. This technique was discovered when gold needlework fragments from the burial of a distinguished Sarmatian woman located in Soklova Mogila, Astrakhan oblast, were studied (Yelkina, 1986). It was this technique that was applied by the Noin-Ula embroiderers, with woolen thread used as the outline.

The highest level of the Noin-Ula needlework shows in that the art images were conveyed not as much through the use of various colors as by applying various thread directions – S. I. Rudnko compared it to brush strokes in oil painting (1962). For gold needlework with heavy threads, this embroidery technique was the only possible. However, it is not characteristic of woolen embroidery, and has not been recorded anywhere else in history. Today, we can only make guesses about the reasons why these remarkable embroideries appeared. It should be noted though that any other embroidery technique common at the time would not apply: the fabric was too thin and the woolen threads too thick.

The wool was mostly died in various shades of red. To produce such colors, several dyes, in the first place, laccain acid (“Indian lacquer”), were used. It is secreted by carteria lacca, insects originating from East India and bordering countries. Laccain acid is a sort of a marker indicating the appearance of new sources of colorants at the threshold of the eras – it is not found among the dyes of the more ancient Pazyryk textiles (Balakina et al., 2006). On the other hand, it was used to dye woolen fabrics discovered in Palmira and Dura-Europos – Syrian hubs of commerce, where fabrics of oriental, Chinese, and western origin amassed (Schmidt-Colinet, Stauffer, 2000).

In Syria, to dye woolen fabrics, a set of colorants from the Mediterranean and India was applied (Bohmer, Karadag, 2000); the Noin-Ula woolen textiles were discovered to have the same composition of dyes. It can be hypothesized that the fabrics and embroidery of the Noin-Ula carpet were produced and dyed in the workshops of Western Syrian, but it does not mean that the carpet itself was made there too.

Portable art

The time when the unique Noin-Ula textile was produced can be determined from the age of the Chinese lacquer cups er bei discovered together with it. Judging by the inscriptions, the cups were made in 9 and 2 BC. (Chistiakova, 2009). Basing on the date of their production, it can be hypothesized that the people buried in the mounds where these artifacts were found had lived during the rule of usurper Wang Mang (9—23 BC).

This was the time of Xiongnu’s virtually continuous plundering inroads on Chinese settlements located near the boundary fortification line. The western area (territory of the present-day Xinjiang, Tarim River basin), through which the northern and southern branches of the Silk Road went, were almost fully controlled by the Xiongnu. Hoping to buy peace on the borders, Wang Mang, through his ambassadors, lavished gifts on the new Xiongnu ruler, Chanyu Uyan-Guidi (Krol, 2005).

During this period of unrestrained pillage and enrichment, the Xiongnu graves, which by the late 1st c. BC began to be constructed similarly to the Han burials, were being filled with foreign artifacts. This also refers to the embroideries found in the Noin-Ula tumuli, which could have been part of the Chinese gifts to Chanyu or booty. On the other hand, we cannot rule out S.I. Rudenko’s proposition that the carpets could have been produced at the Xiongnu headquarters by foreign craftsmen from the overseas materials.

The popularity of embroidered carpets with the Xiongnu elite can only be attributed to their portability, highly suitable for the nomadic way of life. In contrast to frescoes, embroideries were able to travel, supplying a model to emulate. It is known that there used to be special model collections for mosaic makers, which explains the same compositions in Gallia, Syria, Rome, and Egypt (Sidorova, Chubova, 1979). In the same way, model collections could have been used to copy intricate patterns and ornaments on textiles. It is not a question of a mere reproduction but rather of “quoting” separate elements, scenes, things, and ornaments.

These facts testify that it is not always appropriate to equal the personalities depicted on the textile with the artifact makers. Textiles, the same as frescoes, mosaics, and sculptures, could show not only the representatives of the people to whom the embroiderers belonged but also their nearby and remote neighbors, characters of epic tales and cult scenes.

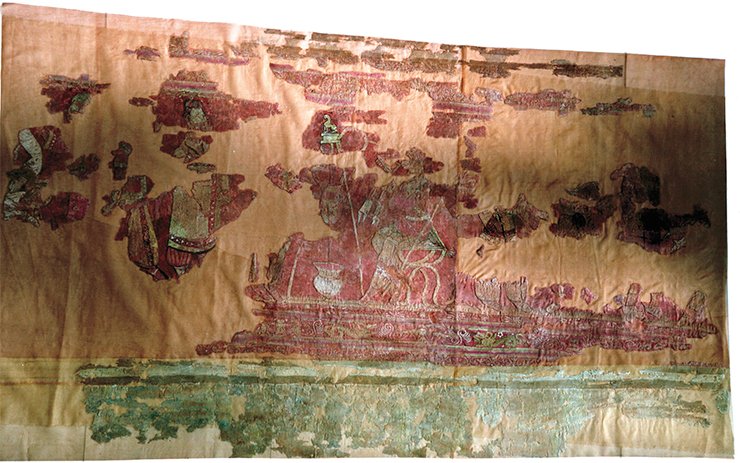

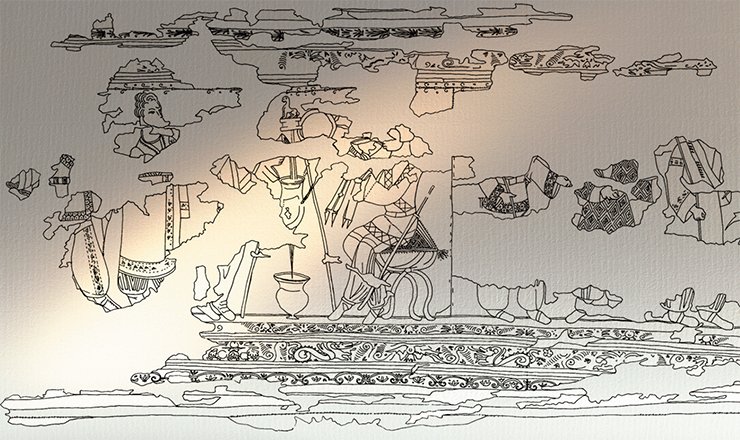

The royal folded chair

A complete restoration of the carpet discovered in the 20th Noin-Ula kurgan by the Russian-Mongolian expedition has proved impossible. The embroidery pattern has partly disintegrated, and so has a large part of the support fabric. Luckily, the central, that is the most important segment of the composition embroidered on the carpet is preserved the best.

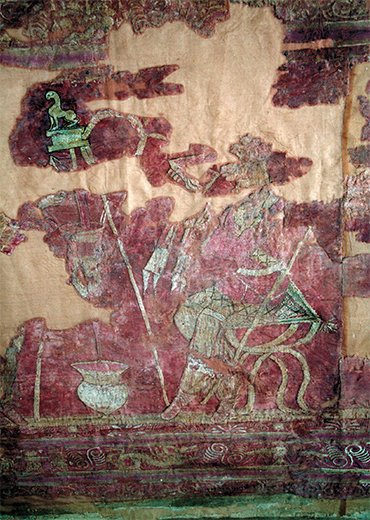

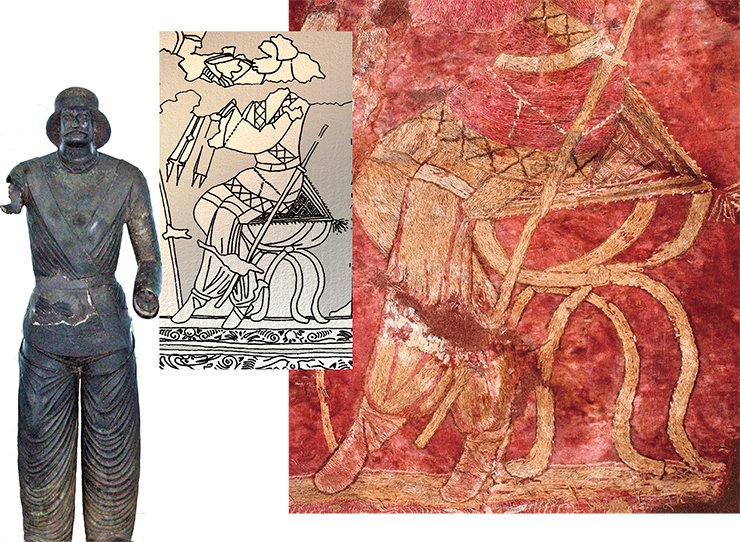

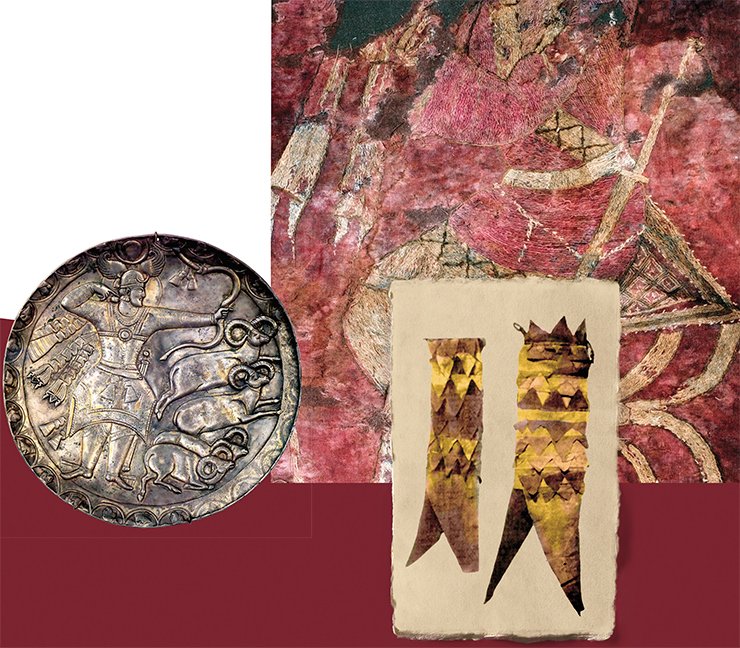

All the men depicted on the carpet are wearing the so-called Parthian costume, which did not differ critically from the attire of other Saka groups (Pilipko, 2001). One detail, however, is original – two flying ribbons ending with two triangular cloths. They can be seen both in the depiction of the main character as well as in other fragments. What do these extraordinary decorations mean?

Similar ribbons can be seen on the depictions of Athena Pallada on the coins of the Indo-Scythian king Azes II, whereas on the earlier Greek coins of Menander I Soter the goddess is shown with a scarf with two triangular prominences at the ends. (L’Asie des steppes, 2000). Possibly, the triangular prominences in the Greek original were nothing but draped ends of fabric but what we see on the carpet is two triangular cloths sewn on to the light, probably silk, ribbons.

Similar ribbons became a common attribute of later, Sassanid depictions: “An essential part of the king’s attire is numerous flying ribbons. A ‘cloud of ribbons’ fluttering around Shapur I was also mentioned by John Chrysostom” (Trever, Lukonin, 1987). These must have symbolized Farn, divine fortune and glory, which explains their presence in the clothes of Iranian rulers.

Suspended to the left side of the sitting man is a long rider’s sword. It is attached by the belt, probably hung on the sheath bracket. As early as in the first centuries AD this manner of fastening swords was widely spread from Korea to Eastern Europe (Khazanov, 2008). On the whole, all the weapons worn by the characters are of Central-Asian origin.

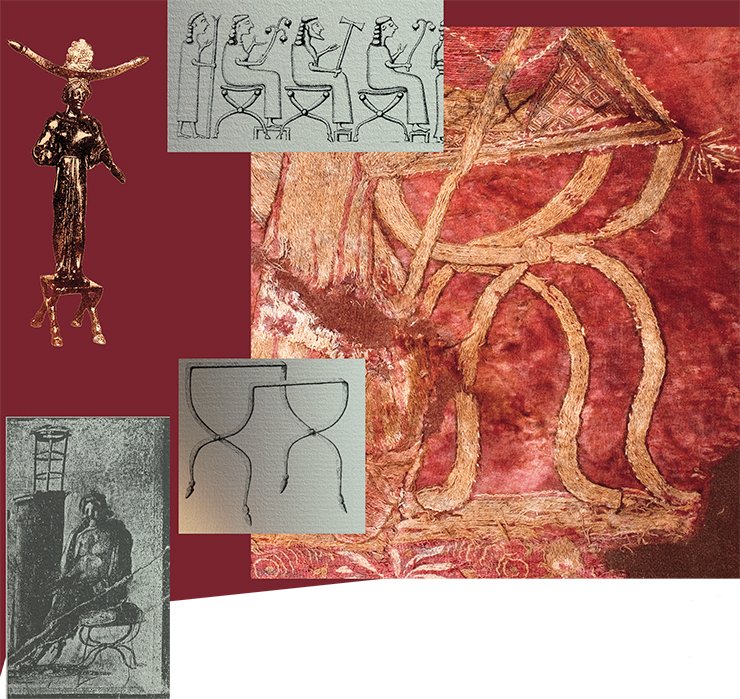

Standing out particularly is a folded armchair – an item known since the old times but not typical of nomadic peoples. A similar armchair, the ends of whose legs were made in the shape of hooves, had only been discovered one other time, in the burial of a high-placed nomadic warrior in Tilla Tepe (early 1st c. AD) (Sardianidi, 1989). It can be speculated that among the Iranian-speaking nomads folded chairs were high-status things, possibly analogous to the king’s throne.

Sacred drink

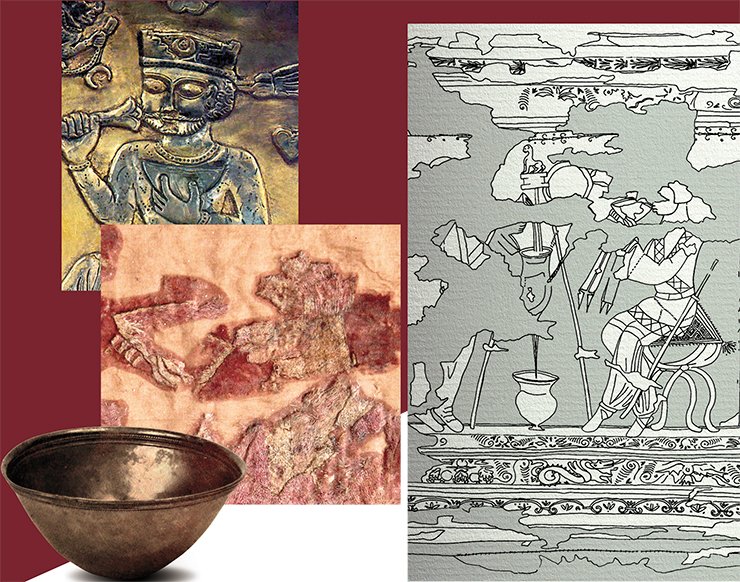

In the center of the composition is a tripod for filtering drinks (possibly, wine). Filtering wines was a must since, in the ancient times, they could not make wine without dregs. In order to avoid excessive fermentation, which turns wine into vinegar, the Greeks, for instance, added to the wine resins, cinder from burnt vines, plaster, lime, and even crumbled marble.

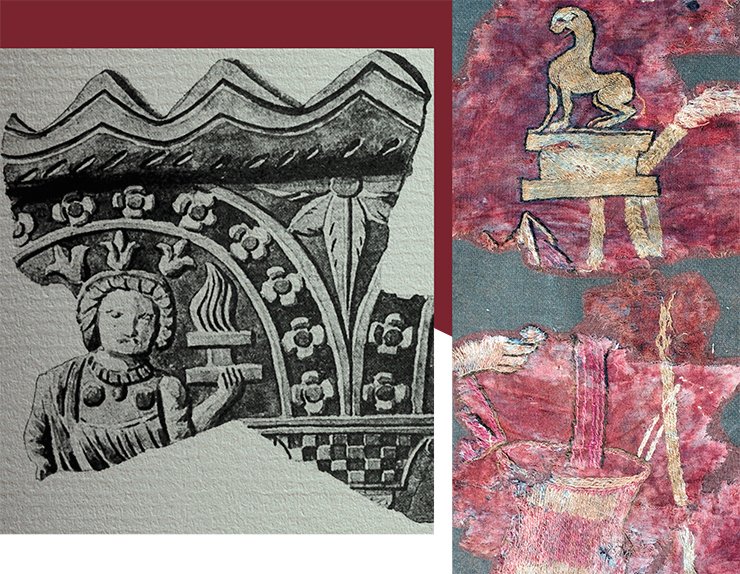

The tripod’s central leg is topped with a rectangular-shaped finial with indents, depicting a predator – a panther, a leopard, or a cheetah. The depiction of a panther can symbolize Dionysus in the wine-drinking scene, emphasizing the Dionysian character of the event.

On the other hand, it cannot be ruled out that in this particular case the carpet shows Roman colors – one of those captured by the Parthians during the inglorious military campaigns waged by Mark Antony and Crassus. A certain type of colors is known to show the genus – the patron of the whole military unit. “Most commonly, various animals were used for this role and, beginning with Augustus, signs of Zodiac” (Rubtsov, 2003, p. 107). The emblems of legions depicted, among other things, Capricorns, winged horses, wild boars, rams, storks, lions, she-wolves, and centaurs (Yann Le Bohec, 2001). If this is the case, the banner embroidered on the carpet is an honorable Parthian trophy, a memento reminding of the victory over the Romans, and the carpet itself can be attributed as Parthian. The thing embroidered above the tripod, next to the panther, is supposedly a wreath. Wreaths used to be depicted on legion banners and also were awarded to Roman officers.

On the other hand, a wreath is a common attribute of the Greek god Dionysus cult, later depicted on various Sassanid monuments. Wreaths, as well as Dionysian characters “received Zoroastrian interpretation and developed into the symbols of one of the most important Zoroastrian fall festivals, Mehregan, accompanied by rituals associated with wine and water. The wreaths were made from flowers and special herbs. They were to be worn by priests as they were reading Jasna during the festive ritual” (Lukonin, 1977, p. 160). Dedicated to this festival are pomegranates and grapes, also found in the embroideries on the carpet borders. Pomegranates and flowers were among the symbols of goddess Anahita, worshiped by Zoroastrians.

Judging from the archaeological evidence, Dionysian cults were widely spread in Central Asia during the Hellenistic time. “This was a melt of Greek and local features deriving from the Avestan cult of sacred Haoma” (Koshelenko, 1966, p. 38). Though Zoroastrians had no festival dedicated to Haoma – an ancient divine drink with a psychedelic effect – no cult ceremony could do without it. Originally, the chief priest made haoma himself, drank it, and after that it was offered to everybody present (Doroshenko, 1982). The beverage, which contained several ingredients, had to be filtered.

Wine-filtering tripods for were repeatedly depicted in the feast scenes in the Sassanid and post-Sassanid toreutics (Trever, Lukonin, 1987). On these artifacts, however, the tripod was not placed in the foreground: as a rule, its small-size depiction was in the lower part of the artifact. This must have signified that wine filtering had an entirely practical purpose in contrast to to the obviously sacral action shown on the carpet from the 20th Noin-Ula kurgan.

The carpet depicts a religious ceremony. In the focus of the event is filtering and drinking of wine or haoma by the king (or a priest). Participating in the ceremony are armed men dressed in Saka clothes, wearing a full set of “oriental” weapons: long swords with a straight guard and a long handle, attached to the belt with a clip; sheathed daggers with four blades, to be hitched on the thigh; spears and belts fastened with rectangular buckles. Wearings arms at a festival or a religious ritual is characteristic of Iranians as all Zoroastrians were warriors fighting on the side of good creatures (Boyce, 1994, p. 81). Compositionally, the scene is largely modeled on Achaemenid works of art and belongs entirely to Iranian culture, in which it will find its continuation. The ribbons on the king’s dress, shown in the embroidery pattern, will transform into a cloud of ribbons typical of Sassanid rulers’ clothes, and the tripod for filtering the sacred drink, which must have been built from spears and a banner, will just become an appliance for filtering wine during a feast.

Basing on the combination of characteristic persons, realities (such as costume, weapons, tableware, chair, and ornaments), and the date of the burial mounds in which the textile in question and similar fabrics were found, it can be supposed that the events embroidered on the carpet can reflect scenes from the life of Indo-Scythian dynasties or succeeding Indo-Parthian dynasties.

It should be acknowledged that the carpet under consideration, the same as its analogues from the other Noin-Ula kurgans, harbors a great many enigmas.

We have studied the textile and come to the conclusion that, in all probability, it was made in Syrian workshops and was meant for clothing. The carpet sewn from this fabric and lace was embroidered between the last years of the 1st c. BC and the first decades of the 1st c. AD by Parthians or Indo-Scythians who adhered to a variation of Zoroastrian belief with some elements of Hellenism. The scene depicted on the carpet is that of religious worship, no matter what the king sitting on the folded chair is drinking – wine or haoma.

We seem to have found out not little, and still there remain a lot of questions yet to be answered.

How did these profoundly meaningful artifacts get to the Xiongnu? Was it the loot distributed by a chanyu among his relatives and servitors? Or is it evidence of the Xiongnu-Parthian ties yet unknown to us? What purpose did these artifacts serve with the Xiongnu? How were they used? Answers to these and many other questions may be hidden on the bottom of the Noin-Ula kurgan we are now investigating.

Russian-Mongolian expedition

Noin-Ula, May 2011

References

Bojs M. Zoroastrijcy. Verovanija i obychai. SPb.: Centr «Peterburgskoe Vostokovedenie», 1994. 282 s.

Koshelenko G. A. Kul’tura Parfii. M., 1966. 220 s.

Kradin N. N. Imperija hunnu. M.: Logos, 2002. 312 s.

Polos’mak N. V. My vypili Somu, my stali bessmert¬nymi... // NAUKA iz pervyh ruk. 2010. № 3 (33). S. 50—59.

Polos’mak N. V., Bogdanov E. S. Na 18 metrov v glubinu vekov // NAUKA iz pervyh ruk. 2006. № 6 (12). S. 14—23.

Pugachenkova G. A. Iskusstvo Baktrii jepohi kushan. M., 1979.

Rudenko S. I. Kul’tura hunnov i noin-ulinskie kurgany. M.; L.: Izd. AN SSSR, 1962. 203 s.

Trever K. V. Pamjatniki greko-baktrijskogo iskusstva. L. 1940.

Trever K. V., Lukonin V. G. Sasanidskoe serebro. Sobranie Gosudarstvennogo Jermitazha. Hudozhestvennaja kul’tura Irana III—VIII vekov. M.: «Iskusstvo», 1987. 155 s., s ill.

Hazanov A. M. Izbrannye nauchnye trudy: Ocherki voennogo dela sarmatov. SPb.: Filologicheskij fakul’tet SPbGU, 2008. 294 s.

Shljumberzhe D. Jellinizirovannyj Vostok. M.: «Iskusstvo», 1985. 203 s.

Bohmer H., Karadag R. Fabanalytische untersuchungen / Schmidt-Colinet A., Stauffer A., Khaled Al-As Ad. // Die textilien aus Palmyra. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 2000. P. 82—89.

Ghirshman R. Iran. Parther und Sasaniden. Munchen: Verlag C. H. Beck, 1962.

Marshall J. Taxila. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951. V. I. 391 p.