The Big Steppe Kurgans as Architectural Monuments

The steppes of Eurasia, a wide belt stretching from the Central Asian plateau, the Ordos, in the east to the Danube in the west have been inhabited, throughout the whole history of mankind, by numerous tribes and nations. Burial complexes or, as they are commonly referred to, kurgans are a striking illustration and often the sole evidence of their unique and expressive culture that reached our time. The mounds grouped in bigger or smaller clusters are the most numerous archaeological monuments on the continent and in the course of the past thousands of years have turned into an integral part of the steppe landscape. Yet, in the last two hundred years a great number of these unique burial architectural monuments have been irretrievably lost

The number of tumuli in the Eurasian steppes may reach many thousands. German archaeologist H. von Merhart, one of the first discoverers of the archaeological treasures of “the big steppe,” described the monuments of the past found in the steppes of the Middle Yenisei as far back as in the early 20th century as follows: “… one mound, another, followed by a long row of mounds, then another field studded with black hail-stones – then another mound – more and more graves, yet another field with burial grounds after other burial grounds stretching for miles…” (Merhart, 1926). The same, or similar, landscape was typical of the whole Big Steppe, its European and Asian parts.

When these areas were included in the Russian state, they became involved in active economic activity which caused the destruction of many tumuli. By the second half of the last century, the scale of destruction had become tremendous: dozens of thousands of mounds were demolished, made even with the ground and ploughed up. In Siberia, Kazakhstan, Northern Caucasus, Ukraine, Moldova, and in other regions the tumuli were destroyed as a result of the so-called development of virgin lands or else as a result of gigantic land melioration construction work. Everywhere, the building of large and small water reservoirs, roads and other projects led to the destruction of tumuli.

Some attempts to save the steppe kurgans were, no doubt, undertaken, and not once. Thanks to the dedicated efforts of archaeologists it became possible to prevent the destruction of a great number of these structures, evidence of human culture, including striking and significant burial complexes, finds from which became the pride of many museums. However, we have to admit that, unfortunately, we have lost far more than we have preserved.

Besides, kurgans, especially bigger ones, have been robbed for centuries. Unfortunately, the same is taking place today, even on a larger scale. Finally, kurgans as archaeological monuments were damaged as a result of the excavations carried out for scientific purposes, especially at the beginning of their study.

Tumuli are Not Just Mounds

The first scientific study of tumuli is associated with the name of D. G. Messerschmidt, a well-known German scientist in Russian service, who in 1722, during the expedition to Siberia, excavated several kurgans in the Minusinsk Hollow. During the three centuries that elapsed since then, archaeologists dug a lot of tumuli in Eurasian steppes; the artifacts found in those mounds became the main, often the sole virtual materials for studying various historical epochs.

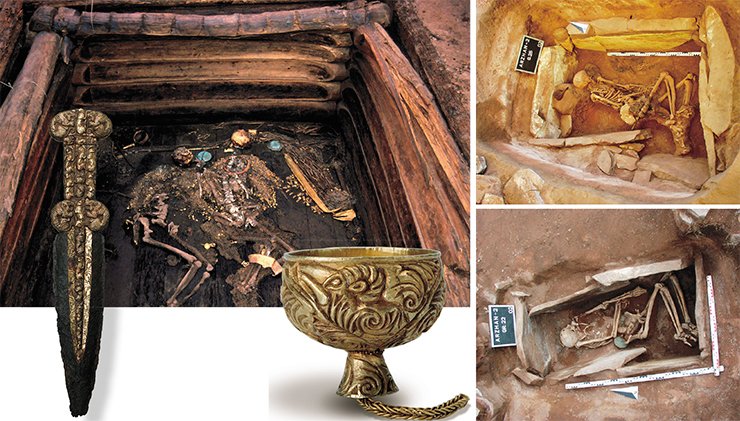

The richest mounds, with hundreds, sometimes thousands of artifacts made of precious metals, were discovered in the kurgans of the early Iron Age nomads, the larger part of which was dug in the 19th and 20th centuries. Unfortunately, the documentation of early excavations (when it took place at all) left much to be desired. The methods of archaeologists of those times were practically no different from those of grave robbers, and their main objective was finding valuable, spectacular things, while ordinary material was often thrown out. Thus, up to now, only an insignificant part of the finds from the excavated tumuli, even the most well-known, has been introduced into scientific circulation.

Since the mid-20th century the methods of field work have been improving; the researchers have started recording the so-called “mound embankments” more thoroughly, too. Accumulation of new data resulted in a qualitative leap in the understanding of the significance and role of kurgan monuments. Thus, M. P. Gryaznov, a Russian historian and archaeologist, formulated (1961) a concept that kurgans are not just mounds; rather they are very old architectural structures that lost their shapes and took the shape of round hills. However, this promising idea gained support only on the part of those, not very numerous, researchers who came to perceive the tumulus as a holistic archaeological site, including not only the burial objects and tombs, but also the design of the kurgan itself.

Unfortunately, in spite of all the advanced ideas, the concept of a kurgan as a certain additional filling above the tomb prevails in archaeology to this day. Even now, when kurgans are excavated in Eurasia, mound embankments do not get sufficient attention: the researchers are more interested in the finds from the tombs. In the first place, this is connected with the fact that the overwhelming majority of the excavations are “rescue operations.” Respectively, they are generally conducted in haste; hence, a lot of significant information, including that which is related to the kurgan structure, is not properly documented. The Issyk Tumulus in southern Kazakhstan and Tolstaya Tomb in the Ukraine may serve as examples of this approach: even the area immediately adjacent to the kurgans was not investigated there. Therefore, no wonder that our knowledge of the kurgan architecture as well as its regional features still remain rather limited.

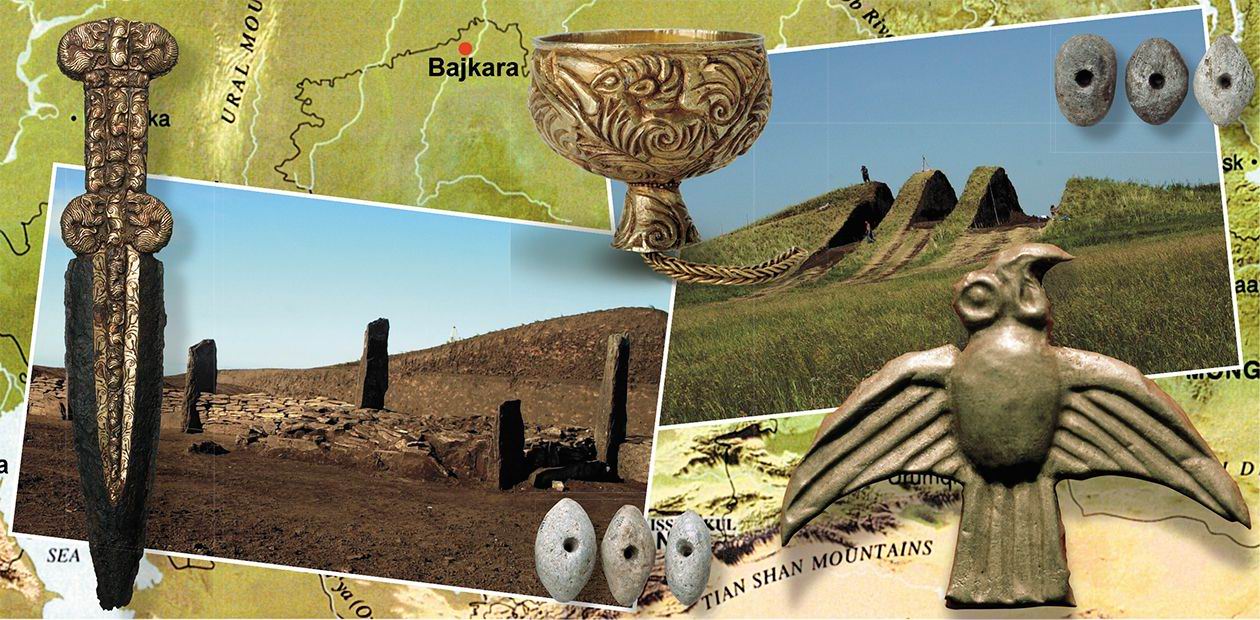

Luckily, in recent years the situation has been changing, first and foremost in the Central-Asian region, where a few fairly large early Iron Age kurgans (Baikara, Arzhan-2, Barsuchy Log and some others) have been studied by joined efforts of Russian, Kazakhstan and German researchers. Another example is large Bronze Age Marpha Tumulus in Northern Caucasia, where excavations are being carried out now.

Large tumuli like these, usually referred to as élite or great tumuli, yield maximum scientific information because they served not only as burial grounds for nobility, but also as sites for performing some complex, sometimes dramatic burial and funerary ceremonies whose traces may be found on these monuments.

Nowadays such joint investigations are conducted employing a multidisciplinary approach, which means that not only archaeologists, but also geophysicists, soil scientists, palaeobotanists, palaeozoologists, anthropologists, and geneticists, as well as representatives of other sciences participate in field work. As a result, both the volume and quality of scientific information obtained during the excavation of kurgans, increase immeasurably.

Turf Pyramids

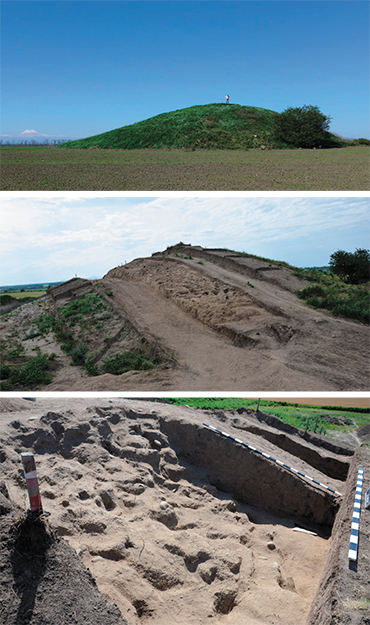

One of the first large kurgans that was studied with a variety of modern science techniques, and the burial structure of which was studied in detail during the excavation was the Baikara Tumulus in Northern Kazakhstan. Actually, it is one of the biggest kurgans in the North- Kazakhstan forest-steppe: at the beginning of the excavations its diameter amounted to 85 m, and the height was 7 m.

Built in the 5th century B.C., the large Baikara Tumulus proved to be a complex architectural construction: to build it various materials (stone, timber, clay) had been used, layers of turf in the first place. Everywhere in the steppe, the tumuli were erected employing a similar technology. These are large tumuli in the Ukraine and in Northern Caucasia, the Filippovskii Tumulus in the South Urals, and some others. The size of the Baikara Tumulus, the complexity and thoroughness of its structures testify to the fact that the building required not only a huge expenditure of materials and labor but also careful planning and supervision based on experience accumulated in the course of erecting such structures.

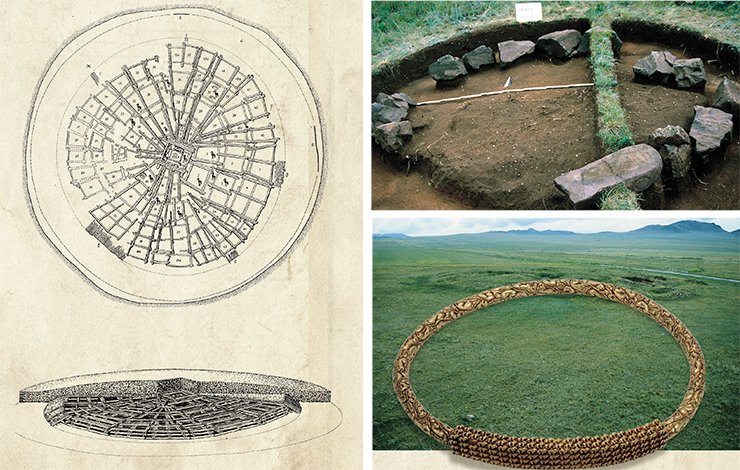

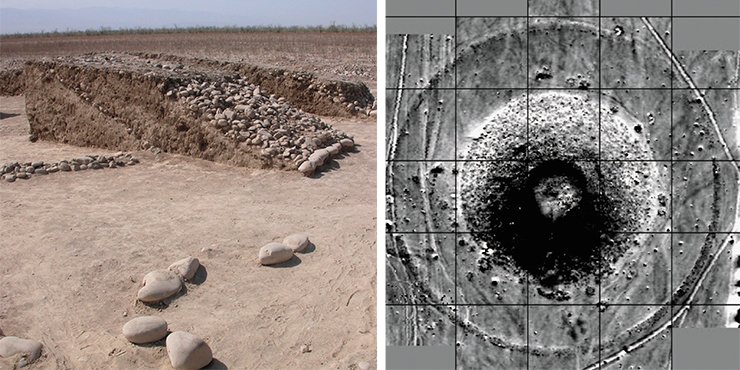

The exterior of the large Barsuchy Log Tumulus in the Minusinsk Hollow (the Middle Yenisei), which was built approximately at the same time as Baikara, differs drastically from the latter. Prior to the excavations, Barsuchy Log had been a pyramid with a rectangular stone wall (this local architectural tradition is characteristic exclusively of the Middle Yenisei), whereas the round stone-shelled Baikara was surrounded by a ditch. But they were both built from pieces of turf in compliance with ancient common practice: three steep slopes and one gentle slope, and a flat top. The tumuli were excavated according to one and the same method: in parallel sections, preserving seven stratigraphic edges, which made it possible to trace in detail the design of the structure, as well as to elucidate traces of ritual ceremonies that accompanied each of the four stages of its construction.

The inner core of the Barsuchy Log Tumulus, a rectangular platform in shape, was made with mortar of well-kneaded blue-grey clay with a lot of river silt. In the Early Iron Age tumuli of Eurasia, such a technology was observed for the first time; this fact makes us re-evaluate the level of development of building practice of early nomads.

Likeness between the two tumuli clearly testifies to similar religious beliefs, traditions, and culture of their builders. The origins of this likeness should be sought in Central Asia, where the oldest of the monuments known today, that is Saka Burial monuments – Chilikty (Eastern Kazakhstan) and Arzhan (Tuva)-- were studied.

Funeral Feast at the Foot of the Tumulus

In the Uyuk River valley in the Yenisei Basin, a great kurgan necropolis including a chain of four large round stone platforms is situated. The westernmost of them is the Arzhan Tumulus, the most ancient monument of the Saka-Scythian time dating from the late 9th to the early 8th centuries BC. Excavations of the 1970s showed that this tumulus, 120 m in diameter and 4 m high, was a complex wooden structure with radially arranged burial chambers spanned by massive walls of stone slabs, where humans and horses had been buried.

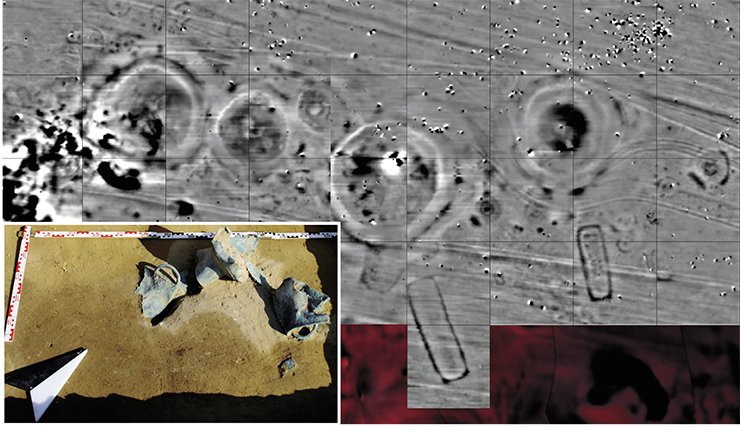

The Arzhan-2 Tumulus, the easternmost stone platform, 80 m in diameter and up to 2 m high, was excavated by the joint expedition of the German Archaeological Institute (Berlin) and the State Hermitage (St. Petersburg) with an active participation of specialists from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography SB RAS (Novosibirsk). Prior to the beginning of the excavations, geodetic and geophysical surveys of the tumulus were conducted; they showed that the platform was the central part of the complex monument.

The platform itself was built in four stages from sandstone plates and reinforced at the edges by a massive stone shaft. The central tomb contained the remains of two people belonging to nomadic élite, as well as a large number of the so-called accompanying tombs – men’s, women’s and children’s. Some tombs that contained many weapons and gold ornaments were found under the stone shaft, which is indicative of the fact that those people were buried there before the platform was built. The majority of people buried there are likely to have been killed in a bloody ritual prescribed by religious beliefs. Besides, the archaeologists found the remains of 14 horses, and a cache of weapons and horse equipment in the tumulus.

On three sides the platform was surrounded by numerous stone rings of different sizes; inside the rings there were a lot of pieces of charcoal and ash, melted metal parts of horse harness, as well as fragments of burnt bones of horses and cattle and other live-stock (similar stone ring structures had been previously discovered in the Arzhan Tumulus). It is interesting that the burning took place elsewhere: only the unburned residues were put in the stone rings. The south side of the complex was surrounded by low circular stone structures. The large number of bone fragments of cattle and of other live-stock that were found there is a clear sign that these structures, more than once, served for conducting funeral feasts, the final stage of a burial rite. These finds indicate that the complex had been used for fulfilling certain cult rituals over a long period of time.

The excavation of the Arzhan- 2 Tumulus has conclusively proven that it should be considered as a complex archaeological monument which includes not only the tombs and the structure built over them, but also the adjacent area that contains artifacts associated with the constructing of the tumulus and with the ritual actions performed there. All this evidence is not always visible on the surface, but to exclude its presence is obviously impossible, especially in the case of large tumuli.

In this respect, a good illustration is the Alexandropol Tumulus (the Lugovaya tomb) in the Ukraine, the first large tumulus in the European part of the Eurasian steppes, which was completely excavated with a scientific purpose in 1852 to 1856. Research of its periphery, carried out only in recent years, discovered behind the ditch surrounding the kurgan some areas with remnants of several feasts. In the largest of them, surrounding the kurgan in a wide strip for approximately 110 m, the researchers found fragments of about two hundred amphorae, bronze, iron and gold jewelry, as well as eleven tombs that contained the remains of people who had been forcibly put to death.

In 2011, geomagnetic exploration helped to discover the periphery of the Tert-Both Tumulus (Western Kazakhstan), rich in artifacts. Though it had no manifestations visible to the naked eye, a real sacrificial complex with remains of horses and people was found there. In this connection, one cannot but recall the large kurgans near the village of Filippovka (Orenburg oblast), not far from Tert-Both; the 2004 to 2007 excavations there yielded unique finds. Near burial structures, the researchers found fragments of bronze cauldrons and bronze finials, but, unfortunately, the periphery of the tumulus was not investigated.

Colossi Made of Clay

Semirechye (Southern Kazakhstan) was one of the most important cultural centers of the early nomads, as evidenced by a large number of tumulus necropolises found there. Even the first examination shows that once these tumuli had a periphery rich in architectural structures, which in most cases was destroyed as a result of economic activity.

One of the exceptions was the Zhuantobe burial site: its main kurgan has a height of 11 m and a diameter of 113 m. Geophysical surveys found around the mound a large number of round stone structures, under which some tombs were then discovered. All the peripheral area was surrounded by a stone-paved road that may have been built for ritual purposes. Such a design of Early Iron Age kurgans in Eurasia had never been seen before. Moreover, this is the first evidence of the existence of the technology of road construction in Central Asia at such an early time (5th century BC); besides, it was a highly advanced technology: the roadbed was first leveled, compacted and paved with medium-sized stones, over which a layer of clay mixed with small gravel was then applied and compacted. Analogues of such a highly advanced construction level have not been found yet. It is hard to imagine that such an advanced technology was applied only for constructing funeral complexes, but that is another topic that requires special research.

Not only did the kurgan periphery have its own specific features characteristic of Semirechye, but the kurgans were built not of turf, but of thick compacted clay. Then their surface was carefully coated with liquid clay, and the whole structure was faced with a stone shell “glued” onto the surface. The inner, denser structure of the tomb was built in the same way.

We encountered similar construction technology when excavating the tumuli of the Hun-Sarmatian time in Aksuat (Eastern Kazakhstan), where mud-brick burial structures had existed in the Early Scythian times. The tumuli unearthed in the Chiliktinskaya Valley, dating from the 7th century B.C., looked the same.

Adobe structures, rather than mounds, were erected over the tombs in the Early Bronze Age. Excavations of the large Martha Tumulus (4,000 years BC) in Central Ciscaucasia are now being conducted by a joint Russian-German team of researchers; the tumulus belonged to the Maikop culture. The Martha Tumulus was also built from clay blocks; on its periphery some sites paved with clay blocks were discovered, and on one of the sites there was a badly damaged structure made of clay blocks similar to the blocks of the tumulus.

Joint Russian-German investigations of recent years have substantially expanded and changed our idea of kurgans. A fundamentally new, multidisciplinary approach to their study ultimately made it possible to give a precise definition to these archaeological monuments. So, a kurgan is a burial and ritual complex which consists of three parts that make a whole. These are graves, hoards, sacrificial complexes; structures built over them, sometimes complex and monumental, that are architectural monuments in their own right; and the areas that are adjacent to the structure, that is the kurgan periphery, where there are moats, memorial complexes, tombs, artifacts, and culture remains associated both with the construction of the complex and with ritual ceremonies carried out there.

Joint Russian-German investigations of recent years have substantially expanded and changed our idea of kurgans. A fundamentally new, multidisciplinary approach to their study ultimately made it possible to give a precise definition to these archaeological monuments. So, a kurgan is a burial and ritual complex which consists of three parts that make a whole. These are graves, hoards, sacrificial complexes; structures built over them, sometimes complex and monumental, that are architectural monuments in their own right; and the areas that are adjacent to the structure, that is the kurgan periphery, where there are moats, memorial complexes, tombs, artifacts, and culture remains associated both with the construction of the complex and with ritual ceremonies carried out there.

A new perception of tumuli requires of the archaeologist certain drastic changes in the methods of study. Participation of other scientists in the research makes it necessary to take into account the specifics of their work during the excavations, such as facilitating sampling for laboratory tests, etc. This enhances the responsibility of archaeologists in carrying out field work and, of course, should be reflected in their officially adopted methods. So far, we only have the excavation methodology adopted by the Moscow Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences in 2011, according to which the basic elements of a tumulus are a “mound; buried soil, ... i. e. the surface layer of soil with vegetation on which the mound was sprinkled; the “mainland” – the layer of soil below the buried soil.” The document does not contain a single word on the kurgan periphery; neither has it raised a question of multidisciplinary studies. And in this sense this methodology is suitable only for tumuli in Ciscaucasia, one of the many regions in the Eurasian steppe zone.

This situation has been corrected by “The regulation on the procedure for conducting archaeological field work and compiling scientific reporting documentation,” adopted in November 2013. In the document, it is required to make a study of adjacent to the mound“...area on which small ditches, powders, feasts, remains of ancient fields and the like can be detected.” However, the kurgan is still referred to as a mound over tombs, not as remains of an architectural structure. As a result, the wrong approach determines, to a great extent, the further fate of the monument. In other words, a large number of tumuli excavated annually are not investigated comprehensively, one of the main elements (the periphery) not being examined at all, and the architectural structure continues to be studied as a “mound.”

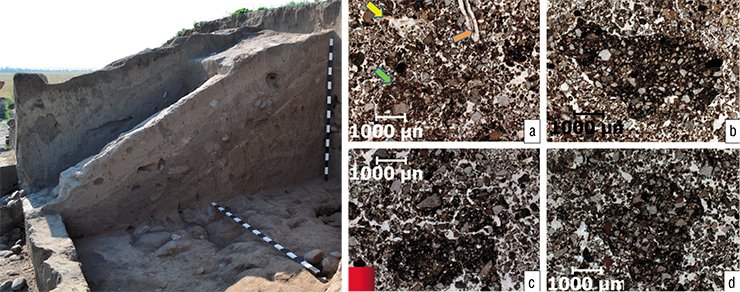

A SOIL SCIENTIST’S VIEWThe material from which, in fact, the tumuli are stacked is examined much less frequently. The terms “mound” and “addition” are commonly used in the descriptions, which does not presuppose the study of the tumulus as a single, purpose-built architectural complex. As a result, the structural features of the mound material and the forms of the original structures are practically not studied; hence, no methods or approaches to solving these problems have been developed. The 2013–2014 paleobotanical study of the Martha Tumulus in the Stavropol krai, made in conjunction with the archaeologists, can be called a pioneering investigation. The methodological approaches to the study of earthen tumulus construction had to be developed literally on the move. When working on the Martha Tumulus the archaeologists used a non-standard technology in which the surface was scraped (the soil from the surface was removed layer after layer) manually, with separation of clay construction blocks. In order to study the soil, the same procedure was performed on outlier edge 3 on the south side of the mound.

The upper granular layer appeared not to have been processed by soil-formation and was the result of a recent displacement of the material. It was followed by a sod horizon containing humus, the soil that was formed on the surface of the mound. A horizontal sweep showed that it was ordinary soil of rough-lumpy structure typical of modern virgin soil, penetrated by plant roots, pathways of earthworms and burrowing animals. The next horizon, according to soil science concepts, had to be a subhumus transitional horizon of modern soil, with columnar-lumpy structural separateness, as it actually proved to be.

Thus, the first field study allowed us only to conclude that the surface of the kurgan was so deeply affected by modern soil formation that “by eye” it is impossible to determine whether the material for constructing the kurgan was placed there in the form of specially molded blocks or poured. The next step was chemical analysis and micromorphological study of the samples. Whereas for chemical analysis usual “loose” soil samples were used, the micromorphological study used undisturbed soil monoliths of size 3 × 5 cm, of which, after special impregnation, thin sections with a thickness of 30-50 micron were made. It is in these samples that the specialists were able to detect the presence of obviously “foreign” microfragments which consisted of much more tightly packed “foreign” material saturated with fine-dispersed (clay) substance.

Can we treat these microfragments inside the material of the upper part of the kurgan loosened by soil-formation as the remains of the “bricks”? In other words, can they be reliable evidence that the building material was artificially mixed, compacted and placed in the kurgan in the form of already molded blocks? To answer these questions, we have compared the microfabrics taken from two horizons of soil on the surface of the kurgan with modern soil and with the soil buried under the kurgan. It turned out that such unnatural soil compaction and enrichment in clay are distinctive only of the microfragments from the soil horizons on the kurgan surface.

The next step was a test for phytolites (determining the silicificated residues of vegetation and other biogenic forms) of the most well-preserved bricks from the deeper layers of the Martha Tumulus structure, which was conducted by A. A. Golyeva, Doctor of Geography at the Institute of Geography RAS (Moscow). The analysis showed that no herbal chaff had been added into the clay when it was mixed; otherwise, the samples would necessarily contain large amorphous residues, and the structure of the discovered phytolites would be more homogeneous. However, flint skeletal elements (spicules) of sponges and the fossil plants of cane were quite regularly found in the samples, which may be attributed to the addition of river silt to the “bricks.”

So, the work carried out in the surface horizons of the mound structure resulted in identifying some remains of artificially mixed and compacted material enriched in clay. However, intense processes of soil formation have made it impossible to determine the form (bricks, blocks, etc.) in which this material was placed into the structure. To create the structural elements of a tumulus, the ancient builders used the material from lower soil horizons enriched in carbonates (loess), and also, possibly, river mud. All the ingredients were carefully mixed and compacted, while fine clay served as a binder.

It should be taken into account that any kurgan, during its long life on the surface, inevitably changes as a result of various environmental factors: wind, rain, snow, vegetation, burrowing animals, etc. This leads to the destruction and loss of the original appearance of the architectural structures, especially of their surface and upper (0.5—1.0 m) layers. This accounts for the fact that the overwhelming majority of archaeologists who study kurgans still perceive them as mounds, which have no regular design features. Besides, the ancient builders used the wattle- and- daub construction technology, which did not help to preserve the structure either.

At present, archaeologists continue to study the Martha Tumulus. In the deeper layers of the kurgan, its structural elements should be preserved much better, and their detailed study will undoubtedly help shed light on the tumulus building history and reconstruct the original appearance of this ancient architectural structure.

A. A. Khokhlov (Institute of Cell Biophysics RAS, Pushchino, Russia)

It is obvious that a new technical and methodological regulation for excavating tumuli should be developed; it should be a law, not a recommendation. At the stage of planning excavations it is necessary to take into account the fact that kurgans, especially big ones, should be examined comprehensively, with the involvement of experts in natural sciences; the work should start with geophysical exploration of the periphery. Finally, it is time to abandon the concept of a “mound.” Otherwise, a huge body of scientific information will be irretrievably lost, as has happened to thousands of kurgans, part of the world cultural heritage, that are vanishing before our eyes.

References

Akishev K. A. Kurgan Issyk. M., 1978.

Akishev K. A. Drevnee zoloto Kazahstana. Alma-Ata, 1983.

Alekseev A. Ju., Murzin V. Ju., Rolle R. Chertomlyk, skifskij carskij kurgan IV veka do n. je. Kiev, 1991.

Molodin V. I., Parcinger G., Cjevjejendorzh D. Zamerzshie pogrebal’nye kompleksy pazyrykskoj kul’tury na juzhnyh sklonah Sajljugema (Mongol’skij Altaj). M., 2012.

Myl’nikov V. P., Parcinger G., Nagler A. Jelitnoe pogrebal’noe sooruzhenie iz dereva v Tuve //Problemy arheologii, jetnografii, antropologii Sibiri i sopredel’nyh territorij. Novosibirsk, 2002. T. 8. S. 396—402.

Parcinger G., Nagler A., Chugunov K. V. Arzhan 2. Istoricheskaja jenciklopedija Sibiri. Novosibirsk, 2009. 124 s.

Polos’mak N. V. Vsadniki Ukoka. Novosibirsk: Infolio, 2001. 336 s.

Rudenko S. I. Kul’tura naselenija Central’nogo Altaja v skifskoe vremja. M.; L., 1960.

Stepi evropejskoj chasti SSSR v skifo-sarmatskoe vremja. Moskva, 1989.

Stepnaja polosa aziatskoj chasti SSSR v skifo-sarmatskoe vremja. M., 1992.

Chugunov K. V., Parcinger G., Nagler A. Nepotrevozhennoe jelitnoe pogrebenie jepohi rannih kochevnikov v Tuve. //Arheologija, jetnografija i antropologija Evrazii. 2002. № 2 (10). S. 115–126.

Nagler A. Погребальные сооружения раннего железного века степей Евразии //Научное обозрение Саяно-Алтая. 2013. № 1 (5). С. 222—232.

Čugunov K., Nagler A., Parzinger H., Der Fürst von Aržan. Ausgrabungen im skythischen Fürstengrabhügel Aržan 2 in der südsibirischen Republik Tuva // Antike Welt. 2001. Bd. 32. N. 6. S. 607—614.

Čugunov K., Parzinger H., Nagler A. Der skythische Fürstengrabhügel von Aržan 2 in Tuva. Vorbericht der russisch-deutschen Ausgrabungen 2000—2002 // Eurasia Antiqua. 2003. Bd. 9. S. 113—162.

Čugunov K. V., Parzinger H., Nagler A. Der Goldschatz von Aržan. Ein Fürstengrab der Skythenzeit in der südsibirischen Steppe. München, 2006. 144 S.

Čugunov K. V., Parzinger H., Nagler A. Der skythenzeitliche Fürstenkurgan Arzan 2 in Tuva // Arheologie in Eurasien. 2010. N. 26.

Čugunov K. V., Parzinger H., Nagler A. Der Fürstenkurgan Aržan 2. Im Zeichen des goldenen Greifen. Königsgräber der Skythen / Menghin, H. Parzinger, A. Nagler, M. Nawroth (Hrsg.). München, 2007. S. 69—82.

Gold der Steppe. Archäologie der Ukraine. Münster, 1991.

Parzinger H., Zajbert V., Nagler A., Plešakov A. Der großeKurgan von Bajkara. Studien zu einem skythischen Heiligtum //Archäologie in Eurasien. 2003. N. 16.

Parzinger H., Nagler A., Gotlib A. Der tagarzeitliche GroßeKurgan von Barsučij Log in Chakassien. Ergebnisse der deutsch-russischen Ausgrabungen 2004—2006 // Eurasia Antiqua. 2010. Bd. 16. S. 169—282.

Nagler A., Samasev Z., Parzinger H., Nawroth M. Süd-Kazachstan: Kurgane Asy Zaga, Kegen und Zoan Tobe // Archäologische Forschungen in Kazachstan, Tadschikistan, Turkmenistan und Usbekistan. Berlin, 2010. S. 49—54.

Nagler A., Samasev Z. Skythenzeitliche Kurgane in Ostkazachstan: Kurgan-Nekropole Aksuat // Archäologische Forschungen in Kazachstan, Tadschikistan, Turkmenistan und Usbekistan. Berlin, 2010. S. 47—48.

Nagler А. Grabanlagen der frühen Nomaden in der eurasischen Steppe im 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. // Unbekanntes Kazachstan. Archäologie im Herzen Asiens. Bochum, 2013. Bd. 2, S. 609—620.