The Legendary Nildin Dish

The story of this remarkable finding dates over 20 years back, when the author of this article together with Izmail N. Gemuev, untimely deceased, were working in the watershed of the river Northern Sosva. Here, in yurts scattered along the river banks live the Mansi, a small nationality kin to the Khanty, Hungarians, Estonians, and Finns. They hunt and fish, worship their gods, offer sacrifice, and observe their customs… Signs of their original culture include sanctuaries preserved in the recesses of Siberian taiga. It was in one of these "open-air cathedrals" that a richly-decorated ancient silver dish was found, which is now kept in the archives of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, SB RAS

On that hot day in July 1985 we, led by a guide, began our trip along a tiny winding river blocked up with fallen tree trunks. It was quite dangerous—our motor boat would speed up, push down a log at full speed, slow down, pass across the log without stopping, and then pick up speed, and shoot up to the next hurdle. I would not be have been surprised at all if we had ended up crushing the boat’s bottom and breaking or drowning the engine but the Mansi gods must have been waiting for us: the crazy half-hour ride had a happy end and we found ourselves on the path leading up a high bank.

A few minutes’ walk from the bank, at the border of the forest, was a sacred barn, home to Polum-torum-pyg (Son of the Pelym God), which is the patron spirit of the nearby settlement Verhneye Nildino. Two meters from the barn was a four-legged table, and a little farther away was a camp-fire site and stakes with the faces of forest spirits carved on them.

The Mansi used to come here several times a year, and main sacrifices would be offered in the winter, soon after the New Year. A horse was considered to be the best offering. It was tied to a special pole, its back was covered with a sacred blanket depicting the Heavenly Rider Mir-susne-khum (The World of the Man Looking Around), who was a brother of the Pelym god. Then the animal was stunned with an ax head and stabbed. The first plate filled with raw meat and blood would be put at the stoop of the barn: the god was thought to feast on the vapor rising from the meal.

People would plead Polum-torum-pyg for a good hunt and family wellbeing, and thank him for protection. They would then carve the animal and cook it right there, in a huge cauldron. The sacred place had a high status so no women were allowed.

…Our guide propped up a ladder — a log with hacks to help one climb up and opened the door. One by one, we looked in: at the back wall, sitting on a low platform was an anthropomorphic figure of the Pelym god’s son in a black gown and three pointed cloth hats. Along the room, sacrifice scarves were hanging on perches; next to the door we spotted cigarette and tea packs, matches, and a tin bowl with wine cups.

In the chest to the right from the door, in two hat jackets, one inside the other, was a large silver dish, wrapped in kerchiefs and custom made clothes with brass buttons. According to our guide, during sacrifice offering, the dish would be carefully taken out of the chest by the leather strap and hung on a tree branch.

The Mansi believed the dish depicted their gods including Polum-torum, Mir-susne-khum, Thunder god, and Water tsar and his sons. In fact, the sanctuary played the role of an open-air cathedral and the dish was its main icon.

In the same year (1985) the dish was purchased for the Museum of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography. Later, back in Novosibirsk, we could look more closely into this remarkable find called the Nildin dish.

Sacred white metal

The dish was dated based on the images exposed on it: it was made in Central Asia in the 8th or early 9th century. Finding such an ancient bowl in a present-day pagan sanctuary may seem surprising both to laymen and specialists, though the latter might be able to explain it to a certain degree.

Let us remind you of the two common myths associated with the inhabitants of the Trans-Ural territory and their gods. One of them is about Chud Beloglazaya, which has left bronze depictions of its leaders, and numerous treasure-troves of gold and silver products. The second myth, widely known in medieval Western Europe, is about the Golden Woman. “Behind the land called Viatka, on the border with Scythia… there is a big idol, Zlota Baba, which is translated as ‘golden woman’ or ‘golden old woman’; local nationalities worship her and nobody passing nearby will fail to make her an offering.” (M. Mekhovskiy, 1517). As we can see, both the legends are connected with ancient metals.

Northern West Siberia happened to be a store-room for oriental silverware. In the 6th and 7th c. merchants from Central Asia made it to the upper reaches of the river Kama. They used to bring walrus tusks, game birds and furs from the north. Through the Cis-Kama region, the Cis-Ob territory started to get involved in commerce with the south at the threshold of the 7th and 8th centuries. At that time, relations with the west were the only option for the areas located to the east of the Urals as the situation in the southern steppes, where one nomad empire succeeded another, was troublesome. In the west, there was a trade-route along the Volga, whose Cis-Kama and Ural branch carried most of the oriental silver to the north of West Siberia.

Because the white metal was precious and “scared” most of it made it to the Siberian pagan sanctuaries and went on to become ritual accessories. When the cult places ceased to exist or were destroyed, the silver went under the earth to reappear in “treasure-troves” hundreds years later.

In the Lower Cis-Ob region, the following things have been found this way: the 6th-century silver dish depicting angels to the sides of a cross; 9th-century East Persian dish depicting a tsar on the throne; 9th-century bottles from Tokharistan and Iran; 9th—11th-century trays from Asia Minor and Khorezm; a hollow head of a monster from 8th-century Sogd; 9th-century Khazar dipper; 8th-century Byzantine bowl depicting Alexander the Great being taken to heaven by griffins; and others. In the late 19th century, an ancient silver figurine of an elephant was one of the idols at a Mansi sanctuary in the upper reaches of the river Northern Sosva.

Twin dishes

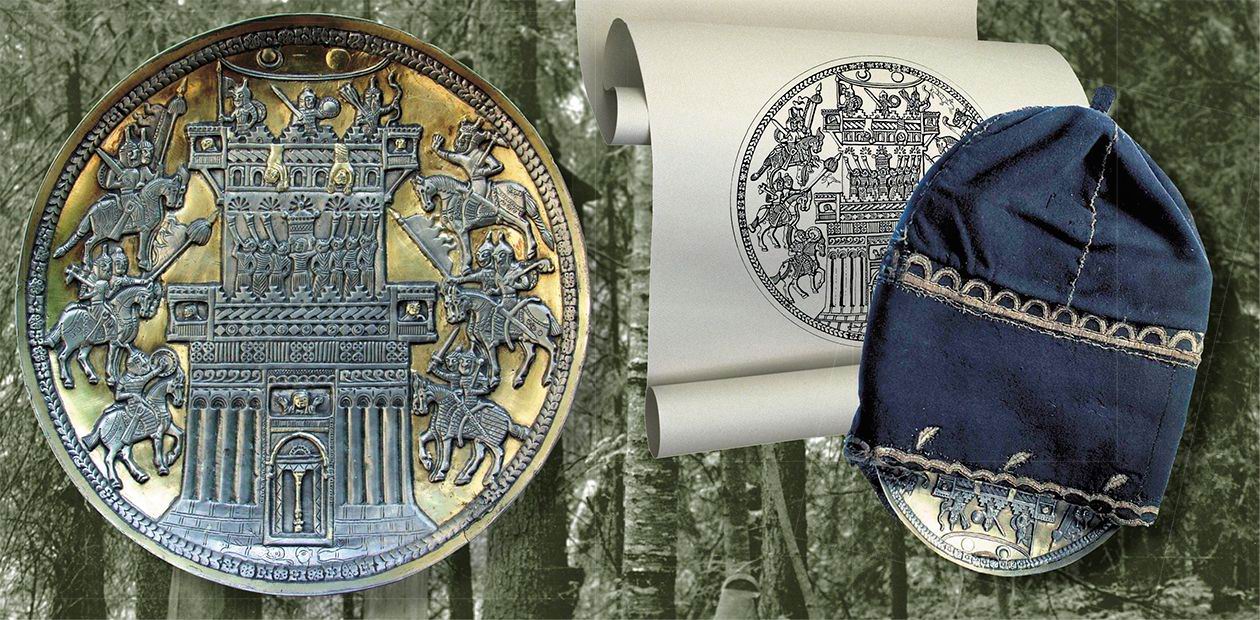

As Izmail N. Gemuev managed to establish quite quickly, the Nildin dish was a twin of the famous Anikov dish found in 1909 near the village of Bolshe-Anikovskaya, Perm province, and now kept in the State Hermitage, St Petersburg. The latter dish was in the focus of heated discussions, which lasted many decades, between Soviet and foreign scholars. The experts could not come to an agreement as to the locality where the dish was made, its age and the meaning of its composition.

At first some French orientalists considered the dish to be Persian. In 1939 A. I. Terenozhkin put forward the idea that the dish had come from Khorezm as it exposed a 6th- or 7th-century two-storied castle typical of Khorezm. A.M. Belenitskiy (1959) noted that the architecture of the castle depicted in the Anikov dish was characteristic of most areas of Central Asia; among the scholars who supported this view were A. V. Shishkin (1963)and L. I. Rempel (1982). B. I. Marshak (1971) held that the dish was cast in the 9th or 10th c. from the 8th-century original in the state of Christian Uzbeks situated in Djetisu (Land of Seven Rivers), which used to be situated in what now is south-eastern Kazakhstan.

The composition was also interpreted in many ways: capture of a fortress by Persians and importation of the sacred fire (Sarre, 1923; Reuther, 1938); introduction by a sultan of his army and suppression of the plot against Sultan Sanjar in Merv (Sauvaget, 1940); procession and carrying out of a Zoroastrian burial urn holding ashes (Terenozhkin, 1939).

S. P. Tolstov (1948) associated the dish’s composition with the beliefs of Central Asian peoples in Siyavush, the dying and resurrecting god of vegetation. According to him, the leader was Kei-Khosrov, Siyavush’s son, and the woman raising her hands was his mother; the two corpses on the tower merlons were the murderers of Siyavush. On the whole, the composition plot tells the story of Kei-Khosrov’s victorious comeback, his revenge to the father’s murderers, and carrying out the burial urn holding the remains of the divine founder of the Khorezm dynasty.

G. А. Pougachenkova (1981) interpreted the scene as the siege and defense of a two-storied castle, which lasted day and night and is symbolized by the sun and the moon. Above the first floor, priests are carrying out a relic-holder and performing a ritual worshipping the heavenly bodies. At the entrance, the orant woman priest pleads her gods for mercy.

According to N. V. Diakonova (1970s), the composition looks like a version of “Kushinagar siege” related to the fight for the urn containing the sacred remains of Buddha.

In 1971 B. I. Marshak proposed that the dish illustrated episodes from the Book of Joshua adapted to the Central Asian context; the order of the episodes was from the bottom to the top. At the bottom is the siege of Jericho and Harlot Rahab in the window broken through the city wall; above it is carrying out the Arc of the Covenant accompanied by seven priests with “seven jubilee horns”; and on top of this scene is the capture of the Canaan city and Joshua (on the right), who has stopped the moon and the sun.

And now the newly found Nildin dish appears on stage, of higher quality than the Anikov one, which allows us to look on the former one as the original and the latter as a copy.

Sacred catch

If the Anikov dish was fairly referred to as “famous”, the Nildin dish turned out to be “legendary”.

It appears that back in 1938, in the upper reaches of the river Sosva in the Urals, the well-known ethnographer and archaeologist V. N. Chernetsov wrote down a legend of the silver dish (the scholar did not happen to see it). From the very first pages it became clear that the legend was about the Nildin dish.

According to the main version of the legend, a long time ago some Nenets living in the area of modern Salekhard were fishing and got out a silver plate. One of the fishermen brought it home and hung it onto a pole in his tent’s corner. Three days later he fell ill and died. The plate was taken by another fisherman, and he too fell ill and died three days later. Five more Nenets suffered the same fate. In a few days, seven people—every one who had tried to become the dish’s owner—met their death.

Then the decision was made to turn to a good shaman in order to find out why the people had died and what should be done. “The people got together. They began choosing a shaman. Even though they managed to choose between themselves, nobody dared to beat the tambourine, nobody agreed…Then they found out that there was a girl who was the best shaman…They made a fire, warmed up the tambourine, and the girl started singing and said: “This silver plate is very expensive. It has many gods on it. Tapal-torum* is on horseback, and his son is on horseback too. On the one side of him is Mir-susne-khum on horseback, and at his side is Mir-susne-khum’s son on horseback. The old Water tsar has come out of the water in the middle of the plate. There is a fifth person too: Shakhel-torum** on horseback.” (Boldfaced are descriptions of the figures exposed on the dish. Author)

And the shaman girl, looking at the dish, went on reading a score of a mythical play. It appeared that the Thunder spirit living in the south decided to go down the Ob and fish in the area that belonged to the Water tsar. The latter did not like it, and he ordered to catch the Thunder spirit’s sons and punish them. “Two people went, caught a boat and turned it down. Both the people were caught. The Thunder spirit was looking from above at his sons being caught and taken down, to the city. Their hands were tied, their legs were tied. The sons were killed and hung on an iron bar.” He was then frightened and went to Tapal-torum to ask for help so that they would fight the Water tsar together.

The question of the Nildin dish origin and time when it was made was largely being tackled on the basis of the architecture of the building depicted on it, which was considered to be Central Asian. An interesting detail has been left out though: the upper part of the castle’s hind tower with warriors standing on it must have been made from a sketch of an ancient Assyrian combat.In 1878 during excavations of the palace of Salmanasar III located on Balavat hill, in the vicinity of Nineveh ruins, bronze plates were found, which had been used to bind the gate of the palace or castle (they are now kept in the British Museum). These plates are covered with rows of depictions and cuneiform inscriptions. Some episodes refer to the marches made by Salmanasar III against the kingdom of Urartu (860 B.C.). One of the plates shows Assyrian troops attacking a fortress. The fortress located on top of a mountain is being besieged on two sides. Inside the fortress one can see its defenders, archers and spear-throwers. The explanatory inscription over the depiction says, “Town of Sugunia, of Aram of Urarty”.

What details of the Assyrian plot can be recognized on the Anikov dish? They are semi-circular arcs; figures of two people hanging with their heads down; the archer standing on the right of the fortress wall; the lower warriors’ uniform—knee-long lamellar armor; and shape of the swords. We do not mean that the Nildin and Anikov dishes may happen to be much older but that the Central Asian art has absorbed a lot of earlier southern traditions whose roots are in Iran and Assyria. This is an argument in favor of the hypothesis (Lukonin, 1977) that proto-Iranian art is based on the images and compositions of the ancient East, mostly Assyria and Elam, as well as Urartu and Asia Minor.

«Tapal-torum said to his son: “Take our war horses, harness them and put saddles on them.” So they went out, mounted their horses, and set off.” On their way they decided to call on Mir-susne-khum and ask him to go with them. So they did and told him about their trouble. Mir-susne-khum said to his son: “Go outdoors, catch our war horses.” The son went out, caught both horses, harnessed and saddled them. They went out. Mounted the horses. Five horsemen were riding together.

One time the Water tsar was at home. All of a sudden his house began to stir and heave. He looked out and saw his enemies coming. Five horsemen. Then he came up to the water surface and began pleading with them. When he was leaving the house, the water tsar told his seven sons, seven strong men: “Speak to the Sky spirit. Blow your seven trumpets. The enemies are coming! I’ll plead with them, and you plead with the sky spirit.”

He himself went out, showed up above the water. Pleaded with his enemies. Stretched his hands. His mouth opened. This is how scared he was!

And then they had mercy on him. The Sky spirit would not have them fight either. So they had mercy even though they set off to kill the Water tsar.”

Having told the story shown on the dish, the shaman girl also explained the reason why the Nenets had died: “The dish was taken to seven homes, and so seven people died. Why did you bring it inside? It should be tied to a birch tree.

Wrap this plate into a white deer’s skin. There is a man living in the Verhne (Upper) Nildin yurts. Take the dish there by boat, and that man will have it. It should be kept there.

The Nenets girl told fortunes like that; so she discovered the place where the dish should be kept. The place was found by the shaman. And the dish is now kept in the Upper Nildin yurts.”

It was made by “other” people

Unbeknownst to her, the shaman girl who had told fortunes about the dish got involved in the discussion of Soviet and foreign scholars concerning the dish’s composition.

The figures depicted on the dish were interpreted by the Nenets shaman according to the local mythological tradition. The figure of the woman was identified as the Water tsar lifting up his hands, and seven priests with trumpets turned out to be his sons. In the upper part of the fortress wall the bodies of the murdered sons of the Thunder spirit were hung and one of the two groups of riders were characters of Mansi mythology: Pelym god, Mir-susne-khum, their sons, and Thunder spirit. The second group of riders could probably be looked on by the Mansi or Nenets as the Sky spirit’s warriors who the Water tsar asked for help. And so the equal number of riders on the opposite sides prevented the battle.

It may seem strange that the Nenets girl identified the figures not as her own gods but as the Mansi gods; that she attributed the dish to the Mansi cult and not Nenets cult; and finally that a Mansi legend went about the finding of the dish by a different people. It is not easy to explain, but the answer should be looked for in the Mansi ritual traditions.

Each family, and sometimes its individual members had depictions of their own patron spirits, which were made out of wood, bone, fabric, metal, birch bark, and so on. The making of these fetishes obeyed a few rules. Firstly, they had to be made by another person. Secondly, they had to be bought out from the person who had made them—the future owner had to reimburse the costs, at least symbolically. The costs did not imply just the time and skill needed to make the figurine of the patron spirit but rather the risk of being punished by supernatural powers in case of an unintentional mistake.

The story of the dish may be a reflection of these rules. Since the dish was found, it was considered to have been sent from above and had to become one of the cultural attributes in compliance with the procedures adopted for making a new thing. The Mansi legend laid the responsibility for finding the dish at the Nenets’ door (“it was made by other people”), pointing indirectly that the peace offering—the death of seven people—had already been made (“the dish was bought out” from the Nenets).

Another important detail was emphasized: both in the Mansi and Khanty culture it is was prohibited to keep things considered to be sacred within the living space. The Nenets who violated this rule paid off with their lives. Also the gods were angry with them because they tried to usurp the thing that belonged to others.

Chernetsov took notes of the dish legend twice. On October 22, 1938 he only managed to make some brief notes in his diary, and the full text (an excerpt from which was cited above) was written on November 4. Intriguingly, according to the former version, “seven similar dishes were discovered in the catch”. One of them was sent to Verhneye (Upper) Nildino, and the others “were taken to other places”.

On the one hand, the Anikov dish may have been one of those seven; on the other hand, “similar” should not be interpreted as “having the same plot”—same size, shape or other external features might have been meant.

Many decades of search were crowned by success: in 1999 another “similar” dish cast in Central Asia in the 8th or 9th c. was discovered at a Khanty sanctuary. And the plot of the beautiful bowl, once again, made the scholars gasp: inside a Sogdian palace, wearing magnificent attire and Sassanid shahs’ crowns were the Bible kings David and Solomon…

References

Baulo A. V. Connection of Times and Cultures (Silver Dish from Verhnie-Nildin)//Archaeology, Ethnography and Anthropology of Eurasia.—2004.—№ 3.—Pp. 127—136.

Gemuev I. N. Another Silver Dish from the North Ob Region // Izv. SO RAN SSSR, series on history, philology, and philosophy.—Novosibirsk, 1988.—№ 3.—Issue 1.—Pp. 39—48.

Darkevich V. P. Metal Art of the East. Products of Oriental Toreutics in European Part of the USSR and Trans-Ural Region—Moscow; Leningrad: Nauka, 1976.—198 pages.

Nosilov K. D. Visiting the Voguls.—St Petersburg: S.A. Suvorov’s Publishers, 1904.—255 pages.

* One of the names of the Pelym god

** Mansi’s Thunder god