The Light of Distant Hellas

On more than one occasion Science First Hand has published articles about striking discoveries made during the excavations at one of the burial mounds of a famous burial ground of the Xiongnu nobility from Noin-Ula in Northern Mongolia, carried out by the Russian-Mongolian expeditions in 2006. A silver plate depicting an ancient plot, found at a depth of 18 meters, buried in a splendidly decorated burial ground has become one of the most unexpected and truly outstanding discoveries

It was the end of October, the Mongolian winter with its little amount of snow was beginning, and the expedition was in its sixth month. This amazing silver plate was discovered at the bottom of the burial chamber in frozen clay covering its floor. Having turned the plate over to its front, we experienced a state of true shock: aloof but stern faces of unreal beauty were looking at us. In the frenzy of winter cold enveloping us the naked figures of a man and a woman emanating a warm radiance of the sun of Ancient Greece were defenseless and beautiful.

Judging from the location of the find among the other funeral attributes, the Xiongnu silver plate was used as a falar, a horse harness decoration. There is no doubt though that this amazing piece was not meant as a horse decoration. Before it found itself in the hands of a nomadic ruler in the Mongolian steppes, it had to have a long life full of adventures.

“… An old silver set and goblets with goats”

Evidently, the silver find from the Xiongnu burial mound was originally a so-called emblem (from Gr.: lit. “insertion”), a decoration first made separately and then combined with some object such as a dish or a goblet. Usually, objects decorated this way were not used in everyday life but put on display in wealthy houses as decorations. One of the prime examples of such objects is a dish with a figure embodying the “African province” of Rome found on the Pizanello villa not far from Pompey, among the richest known treasure of silver objects (Boscoreale treasure).

In the beginning of our era, such decoration of table cups and dishes, mirror covers, helmets and horse harnesses with embossed chased silver or bronze gilded medallions was widely spread in Greece, Rome and its provinces as well as in Bactria, India and Libya (Trever, 1961).

Artistic silver of the Greek was an object of worship in Imperial Rome, where it was among collectable items. People could be followed and even murdered for attempting to possess these outstanding works of art. According to Pliny, chased silver items were valued for “their old age alone,” with even obliterated images being in high demand (book XXXIII, LV, 157). They were handed down through families similarly to precious stones. One of the dishes from the treasure mentioned above found by the Pizanello villa by the time of the Vesuvius eruption in 79 AD had been in possession of its owners for 300 years!

It is possible to judge about how valuable these items were and about the crimes committed to possess them by what the ancient authors said about them. In his speech for the prosecution against the governor of Sicily Verres, Cicero said: “Is there any painting or statue in our luxurious and wonderful city which we had not received from the defeated enemies? <…> Where did the treasures of foreign peoples now living in misery disappear when at several villas you can at once see Athens, Pergamum, Kiziik, Miliyet, Chios, Samos, all Asia, Achaea, Greece, Sicily?” (Against Verres. About execution. XLVIII. 127). Juvenal supports him: “Only through crime do they gain access to gardens and palaces, viands, and ancient table silverware and goblets with goats” (Juvenile, Satire I, 70).

Antique images in silver more often repeated the images created by the great Greek sculptors Lisip, Praxiteles, Phidias, Skopas and others. One of the greatest masters of the ancient times Myron was known not only as an unmatched sculptor but also as a master chiseler: the silver vessels made by him were very highly valued by the Roman collectors (Vipper, 1972). The orator Licinius Crassus had two goblets made by another famous master, Mentor, which he bought for 100,000 sesterces; however, he confessed that he never dared to use them because of his reverence for them (Pliny, book XXXIII, LIII, 147)Plunder of Greek artistic treasures resulted in a new fashion spread over the Hellenistic world. In the 4th—3rd centuries B.C. from the Greek originals created in Asia Minor, South Italy, Greece, and Rhodes, moulds for copying were made. These numerous copies are found everywhere from Begram (the ancient Kapisha, Afghanistan) to Taxile (India), to Mit Rahina in the ruins of Memphis (Egypt) and Kherson. However, the Greek originals themselves are small in number: like many well-known Greek sculptures they have only survived to the present in the form of Roman and provincial copies.

It is necessary to point out that in the Roman times the emblems that constitute the main value of silver items were broken off by the “collectors.” (According to Cicero, already mentioned Verres was notorious for it; this lover of the ancient silver even had his own workshop where the old emblems were used for the decoration of new items). It cannot be ruled out that a similar fate befell the silver plate found in Noin-Ula.

Time and place

Classical Greek art briefly continued in the works of a number of art schools of the early Hellenistic Age. Here the Pergamene school should be mentioned in the first place as marking one of the high points in the development of art in the ancient world. Along with copying the silver items of the Classical period, metal art artists created new works reflecting the spirit of the time. By its style, the plate found in the Xiongnu mound can be considered as belonging in the group of original works of art of that time. Most probably, it was created for the decoration of celebration utensils in the second half of the 2nd century B.C. by a silversmith working in the tradition of the Pergamene school.

It is surprising but the images on the silver plate (presenting an intimate work of art) bear a considerable resemblance to the images of the famous Pergamene altar erected in the beginning of the 2nd century B.C. to commemorate the victory over the Barbarians (Gauls).The topic of the Pergamon frieze is the fight of Gods against the Giants. Similarly to the plate under discussion, the images on the Pergamon frieze are made in very high relief, i.e., it can be almost considered to be a sculpture. The main similarity lies in the general tragic nature of both the altar images and those depicted on the silver plate: severe facial expression of the woman and a grimace of excruciating suffering of the man do not match what seems at first to be a playful scene. A similarity can be also found in the mastery with which the figurines positioned at complex angles were made.

Satyr reclines on the spread panther skin. Besides low relief, the skin is distinguished by small frequent incisions: the nozzle, clawed massive paws and a long tail can be clearly seen.The panther was considered a usual companion of satyrs, and they were often depicted with a panther skin streaming behind their shoulders (for example, on clay reliefs in the Metropolitan Museum of Arts)

This remarkable item does not have direct analogues among the ancient silver items known today. There are two silver plates from the Mzymtinsky treasure found in the vicinity of Sochi that can be considered closest in form and framing details but not in their content to the silver plate from the Xiongnu mound. Among them is a round relief frame, with rough holes punched at its edges for mounting to the base which was not preserved. One of the plates showing Scylla was made in high relief and most probably belongs with the works of Pergamene school (it is interesting to note that these items were also used by their last owners as falars). The same refers to the reliefs from Melitopol near Pergamum showing the heads of Silenus and Demosthenes (mid. 2nd century B.C.) decorating the bottoms of silver vessels (Maksimova, 1948).

In the center: Woman

The silver disk from Noin-Ula depicts a woman in high relief sitting on the right knee of a man. She is naked. One of the ends of the veil covering her bent right leg overhangs between her legs in beautiful smooth folds. The other end winds twice around her left forearm and goes over her back.

The silver disk from Noin-Ula depicts a woman in high relief sitting on the right knee of a man. She is naked. One of the ends of the veil covering her bent right leg overhangs between her legs in beautiful smooth folds. The other end winds twice around her left forearm and goes over her back.

A goatskin is flung over the woman’s shoulder covering her right breast with two hoofed legs hanging from under it. A round smooth plate (clasp) can be seen on the woman’s shoulder too. The upper edge of the skin crossing the woman’s chest is decorated in the same way as the edge of the goatskin on a well-known marble statue of a young Satyr (“Satyr with a panther”) displayed in the Royal Museum for Art and History in Brussels. It is a Roman replica of a well-known Hellenistic group from the 2nd century B.C. The skin’s texture is shown through engraving with small incisions.

Probably this goatskin served as a banding for a bow because part of a bow can be seen from behind the woman’s left shoulder. It is depicted not in a traditional way. At a glance, this fragment of the image resembles a veil shot up in the air unnaturally (similar examples can be found in Greek vase painting). But if you pay a little bit more attention to it, you can clearly see a bent line of the bow.

A smooth thick bracelet can be seen on the woman’s right forearm; such bracelets adorn both of the woman’s wrists too. Similar bracelets were painted in gold on the arms of the marble figurine of Venice found in Pompeii.

The woman’s face is oval; she has large eyes and smooth eyebrows. A straight nose is smoothly curved at its end. It does not look like a Greek nose at all if you look at the face in profile, but possibly it was slightly flattened while the item was used. The mouth is small with plump tightly closed lips forming vertical folds at their angles. Gilt diadem (band) separates the curls from her smoothly brushed wavy hair parted in the middle. The hair is rolled along the face and lifted at the back; a curl bent to the cheek is marked with the chisel. There is a smooth ring around the neck.

Between the eyebrows, over the nose bridge there is an urn (Sansk.), “a third eye”, symbolising spiritual essence and spiritual vision. This impression appeared already after the object had been in use (it cannot be excluded that the symbol appeared in this place by accident). According to the idea of new owners, the woman depicted on the silver disk became a female manifestation of a deity in the rank of Buddha. Probably it was then when the nose was slightly altered shaping it more in the “eastern” style by rounding a sharp “Greek“ nose end. (While the Greek depictions of Apollo became the prototypes of early Gandhara images of Buddha, Apollo’s sister Artemis could become its female manifestation (at least on this plate). Where and when did it happen? We could learn some of this object’s history by answering these questions.

From Dionysus’ suit

A young beardless man of athletic build with a handsome face reclines on a panther skin spread leaning on his bent left hand, with his legs astride. The man’s face has a suffering expression underlined by two deep folds by his nose bridge. Between his thick hair thrown back from the lobe but hanging over from one side, a pointed ear crowned in gilt ivy wreath is discernable. Behind his back a gilt tip of the horse tail in relief can be clearly seen.

This is a satyr, half-man, half-animal from the male circle of Dionysus, a god of winemaking and fruit bearing power of the earth. Satyrs cannot control their drinking, do not have any decency and invariably rush to the smell of wine. Praxiteles depicted them as handsome young men, with only the shape of their ears giving away their animal nature.

As for the satire’s posture, the image of a half-reclining young man first appeared on the east pediment of Parthenon dating from the 5th century B.C. and was possibly created by Phidias. Together with all the other Parthenon sculptures and his relief frieze, this work is one of the most valuable items of Greek sculpture that have been preserved to the present. During the Hellenistic period, a drunken satyr was usually depicted in this posture.

The male figure on the silver plate resembles a well-known Roman marble copy from the Greek original dating from 220—210 B.C. of an unknown master of the Pergamene school. (This is the so-called Barberini Faun or Drunken Satyr located in the Glyptothek in Munich, Germany). There are many other figures depicted in similar postures: for example, a bronze statue of satyr from the National Museum in Naples. By his suffering facial expression, “our” satyr resembles the bronze bust of the satyr from Pompeii.

Right by the feet of the sculpture group lies a staff with a sharp-clawed panther paw resting on it. A staff is a typical feature of Bacchic, Dionysian scenes and presents a hook (a stick with a bent end). It is not an accident that the hook is ornamented with a pattern resembling the snake’s skin colouring because it itself looks like a snake, a companion of satyrs and maenads. There is a very ancient myth about the emergence of winemaking, according to which it was from the snake that Dionysus learned to use wild grapes to make wine. The earliest images of maenads on Greek vases attest to the fact that the snakes belonging to them were poisonous and dangerous (Kereni, 2007).

On the right of the woman a thyrsus, one of the Dionysus’ attributes, is depicted. Its top crowned with the Italian pine cone appears from behind the woman’s head. Thyrsus’ bass relief is covered in cross shaped incisions, imitating that it is entwined in ivy and grape leaves. Such technique of decorating the thyrsus was also sometimes used in sculpture images.

A little bit further to the edge of the plate an image of a herm, a special type of Greek (Roman) sculpture, stands out. A herm presented a tetrahedral pillar, originally crowned with the head of Hermes, the messenger of the gods, patron of travelers and guide of dead souls. Afterwards other gods began to be depicted on herms as well.

A small gilt herm depicted on the plate presents a bust-length figure of a thick-haired, bearded man. His face is three quarters turned to the spectator. Supposedly the man wears a stola, a female sleeved dress with a belt. According to Apollodorus, it was a female or similar to female dress that Dionysus received from the Friesian goddess Cybele (Ivanov, 1994). The man’s right arm bent in the elbow holds something at the chest. Possibly, it is a wineskin. His phallus is portrayed in a very naturalistic way.

Most probably the herm depicts effeminate Dionysus as he was imagined during the Hellenistic period. “In Hellenistic art bearded Dionysus is often dressed in female clothes, while sometimes his body shape is effeminate too” (Darkevich, 1972).

In Bacchic ecstasy

The woman is the most important element in this scene. Her facial expression is very stern, if not ferocious. This female image is the closest (if not identical) to that of Artemis on a silver medallion found in Thessaly dating from 3rd century B.C. (now at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens) (Collection Helen Stathatos, Les bijoux antiques par Pierre Amandry, 1953). The face has the same spiritual expression, with a skin flung over the woman’s right shoulder and hoofed legs hanging from under it. The skin is depicted by frequent incisions gathering to the center; the hairdo is bound with a band, with hair curls on the cheek marked separately.

The woman is the most important element in this scene. Her facial expression is very stern, if not ferocious. This female image is the closest (if not identical) to that of Artemis on a silver medallion found in Thessaly dating from 3rd century B.C. (now at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens) (Collection Helen Stathatos, Les bijoux antiques par Pierre Amandry, 1953). The face has the same spiritual expression, with a skin flung over the woman’s right shoulder and hoofed legs hanging from under it. The skin is depicted by frequent incisions gathering to the center; the hairdo is bound with a band, with hair curls on the cheek marked separately.

Judging from a bow by the woman’s shoulder, it is indeed Artemis. It could also be the mythological hunter Atlanta who is considered to be posing as Artemis (Botvinnik, 1991). A goatskin is tied around the woman’s chest serving as a reminder of the tradition according to which people dedicated the goats they kept and sacrificed to Artemis in her temple in Ikaria (Kagarov, 1913).

The goddess pushes the satyr away with her left hand, with her fingers and hand set against his chin. Such a blow can be considered quite professional, capable of knocking a person down. The plot where the image of a drunken satyr is opposed to a stately female image (for example, Marsyas and Aphrodite) are commonly found among the paintings on red-figure vases. A similar scene is depicted on the marble relief at the Neapolitan National Museum. It shows a bearded satyr who grabs a nymph wearing a drop-down veil with both hands, while she pushes him away with the same characteristic gesture.

In the scene we are discussing, the Virgin Goddess known for her man-hating actions is depicted as an ordinary nymph molested by the drunken satyr. All the space under the feet of the personages is covered in broken wavy lines depicting water. Water is the habitat of the nymphs, these eternal objects of satyrs’ passion. It seems that a mistake was made, and the drunken satyr took the goddess-hunter who had come to have a rest by the stream and bathe in it for a nymph inhabiting it. Everybody who saw a nymph in the midday heat went mad: “The middle of the day was the time when the nymphs appeared. If somebody saw the nymphs then, they caught a nympholeptic mania similarly to Actaeon who saw Artemis with her nymphs” (Eliade, 1999). It is well-known what happened to Actaeon after that: Artemis turned him into a stag and then he was torn apart by his own hounds.

Contemptuously menacing expression with which the goddess easily pushes away the maddened satyr with a stately gesture and without any visible effort underlines her divine essence. It can be reminded that on the day of Artemis’ celebration an ancient tradition was practiced when the skin on the man’s throat was slightly cut pointing to the existence of human sacrifice to honour her.

Altogether, the whole scene is Dionysian, Bacchic. The back of the man’s head is thrown back with the movement characteristic of Dionysian ecstasies more than once mentioned in literary sources. The choir in Euripides Bacchae repeats:

“Oh, when will I be dancing,

leaping barefoot through the night,

flinging back my head in ecstasy,

in the clear, cold, dew-fresh air –

like a playful fawn

celebrating its green joy

across the meadows.”

Even though as early as 187 B.C. Bacchic cult was banned by the Roman Senate, it did not stop the Dionysian beliefs from spreading in the Roman cities. Judging by the finds, the cult continued to be practised in Pompeii, where every garden was a Bacchus’ sanctuary.

Long travels

Taking into account the attitude of the Romans to artistic silver, it can be argued that it could not be a commodity for sale or exchange; if it had been intended for Barbarians, then only as a diplomatic gift as attested by the inscriptions on the articles that were found (Cline, 1979).

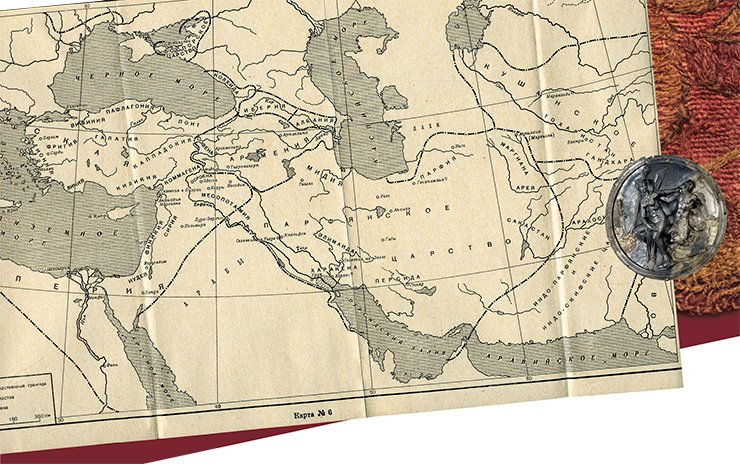

As a working hypothesis, let’s try to reconstruct a possible path of the antique silver plate to the nomad burial mound. Today both written and archaeological evidence exists proving that there were very early direct contacts between Xiongnu and the Romans: Roman legionaries fought on the Xiongnu side during the battle with the Chinese by the river Talas in 36 B.C.

This story is connected with the failed military expedition of the Roman consul Mark Licinius Crassus to Parthia (54—53 B.C). The Romans suffered an overwhelming defeat from the Parthians at Carrhae. Crassus and his son were both killed, while only about less than a quarter of 42,000 Roman legionaries survived in the battle and were captured and sent to Margiana (in modern Turkmenia) to serve in the Parthian army, standing guard on the eastern border of the country.

It was not without a reason that Crassus was nicknamed the Rich because he was filthy rich and continued to plunder the conquered territories during the Parthian campaign. It is possible that the plate was then part of a goblet or another piece of celebratory tableware belonged to Crassus himself. Such tableware could accompany a military leader during the campaign: it is well-known that the Roman military leaders did not like to put up with the limitations of military campaigns (they even took with them statues with which they could not part!). After the defeat the plate could find itself by the eastern borders of the Parthian Empire among other trophies.

Somewhere here the Greek goddess depicted on the silver plate could have been marked with the Buddhist symbol, the urn. It is known that in south-eastern regions of the Parthian state Buddhism was spread already from at least the first century B.C., so the plate could find itself in Margiana among other items (Litvinskiy, 1967). It is possible that one of the new owners of this item, maybe one of the Parthians who headed the Roman legionaries, added a Buddhist symbol to the silver adornment. It is probable that it was then that the plate turned into a falar: it was common for the nomads to give their best things to decorate the horse.

Some of these Roman legionaries found themselves in Sogdiana (modern Tajikistan) in Xiongnu troops headed by Zhizhi Chanyu. This refractory ruler moved on from the native Xiongnu territories after Huhanye Chanyu had subjugated to China. On L. N. Gumilev’s proposal, Zhizhi allied with the Parthians and was helped by the Centurion of the Roman legionaries. He received assistance in building a fortified camp on the Talas River complete with a fortification wall typical of the Roman legions, watch towers and double fencing. When assaulting the Xiongnu fortification during the battle, the Chinese were surprised by a strange order of the troops in the shape of “fish scale.” Indeed, this was how close joined Roman rectangular shields could look (this fact is reported in Chapter 70 of the History of the Early Han Dynasty).

The Xiongnu suffered a defeat in this battle; Zhizhi and his relatives were killed. More than a thousand people among whom there were Roman mercenaries were captured. There is no exact information about what happened with them afterwards: according to one source, a group of captives was given to 15 semi-independent rulers of smaller territories who supported the Xiongnu in their campaign against the Zhizhi.

And this is where the traces of the plate were lost. It is possible that together with the other trophies it found its way to the capital and then, already as a Chinese present, was given to the peaceful Huhanye Chanyu who became the only ruler of the Xiongnu.

But this is all hypothetical… The fact attesting that the fine silver adornment decorating the horse harness was brought to the depths of Central Asia by the Roman legionaries is that a real Roman silver falar was found next to it. Of the articles that never were the objects of trade this find is the most eastern. Both falars were part of the same “collection” which includes plates with dragons and unicorns. Such an expensive horse harness could be part of the present to the Xiongnu ruler from the Chinese court.

Summing up, before finding peace in the grave of the unknown high rank Xiongnu in the mountains of Northern Mongolia, the precious silver adornment could survive for more than a hundred and fifty years in different guises ,hanging hands to become a falar in the end. What an enviable destiny to pass from a string of carts onto the chest of a military horse tearing with it along the boundless steppes towards the enemy.

References

Collection Helen Stathatos, Les bijoux antiques par Pierre Amandry, Strasburg, 1953, Pl. XXXVI, 233.

Kagarov E. G. Kul’t fetishej – rastenij i zhivotnyh v drevnej Grecii. SPb., 1913.

Keren’i K. Dionis: proobraz neissjakaemoj zhizni. M.: Nauchno-izdatel’skij centr «Ladomir», 2007.

Plinij Starshij. Estestvoznanie. Ob iskusstve. M.: Nauchno-izdatel’skij centr «Ladomir», 1994.

Sokolov G., Miron. Poliklet. M.: Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo izobrazitel’nogo iskusstva, 1961. Vipper B. R. The art of ancient Greece. Moscow: Nauka, 1972.

Polosmak N. V., Bogdanov E. S. The past 18 meters deep // SCIENCE First Hand. 2006. N 7 (12). P. 8—17.

The photos used in the publication were made by S. Zelensky and M. Vlasenko