The Three-Dimensional Universe, Where We Are Not Living...

Even the ancient Greeks transformed mathematics from an empirical science into a deductive one. They demanded that proofs of mathematical statements should be concluded from the basic conceptions, and excluding the reference to the experience gained as an argument. Pure mathematics investigates the forms and relations as distinct from material content. For instance, its direct subject is an ideal ball, but not one or another ball-shaped body. Another example: mathematics deals with integers in general but not with aggregates of numbers or individual numbers, and so on. However, no matter how abstract is mathematics, none of mathematicians was in doubt that all their conceptions, theorems and formulas are real quantitative and spatial relations. Mathematical Geometry was the theory of a real space as later mechanics became the theory of motion

Mathematics is a science, studying

the quantitative and the qualitative forms

and relations of reality

Academician A. D. Alexandrov

Outward things are three-dimensional. We got used to think so since our birth — everybody knows what the length, height and width are, i. e., the three primary dimensions of the surrounding space. According to the traditions of different countries, the dimensions of subjects are evaluated in meters, feet, leagues and other standard measures. Let us choose a slightly unusual unit of length for our further discussion. It will be one light year, i. e., the distance covered by the light ray in one year. This amounts to unimaginable magnitude in the conventional linear measure — about 9,46•1012 kilometers.

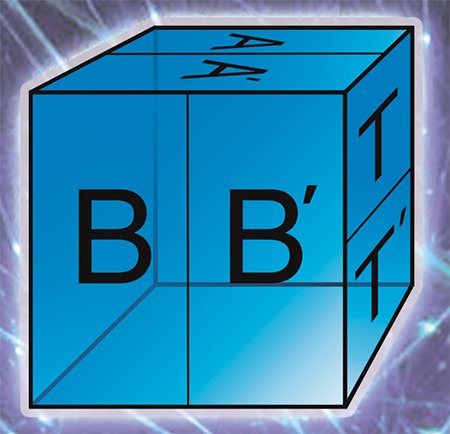

If we mentally cut the cube whose edge length is equal to one light year the house where we live, the terrestrial globe, the Solar System and everything required for the human life, we can easily put inside. For convenience, let us call the cube mentioned above a unit cube. And now let us note the following obvious fact. In spite of a very large size, our unit cube is just a negligibly small part of the Universe.

An imaginary unit cube of this kind can be derived at any other point of space. And at the same time, one could say that two cubes derived at the different points of space are equal. That is the main idea about the essence of the Euclidean manifold. According to this idea, any point of the Euclidean manifold is surrounded by the cube of the corresponding size. More accurately, this can be defined as follows. Three-dimensional Euclidean manifold is the set M3, whose any point is the center of some cube consisting only of points of M3.

By the way, in this definition the size of the cube is not present — it is not necessary to use big cubes. One can also say that each point is contained in the cube with an edge, not exceeding, for example, one micron (10-6 cm). In other words, the space surrounding us is a three-dimensional Euclidean manifold. And now let us try to give an answer to the following question: how is the world outside the unit cube, our Solar System, organized?

A Three-Dimensional Torus and others

If we imagine that the surrounding space is infinite in all the directions, then the following Hadamard Theorem gives the answer about the structure of the surrounding world:

“An infinitely large in all directions three-dimensional Euclidean manifold M3 coincides with the Euclidean space E3”.

The Euclidean space E3 with the rectangular coordinates is generally known, so we will not dwell on the study of its features in detail.

To make our discussion more informative and interesting, let us assume that the space surrounding us is closed, i.e., has a finite size and no boundary. In other words, let us ask the question: how the closed three-dimensional Euclidean manifolds or Euclidean forms are organized? The theorem proved by J. Wolf (1982) gives the full answer to this question:

There exist exactly ten three-dimensional Euclidean forms, six of them being orientable, the other four – non-orientable manifolds.

All the Euclidean manifolds are constructed similarly, but it is necessary to note that to obtain some of them one should use a cube, and for others – a regular hexagonal prism.

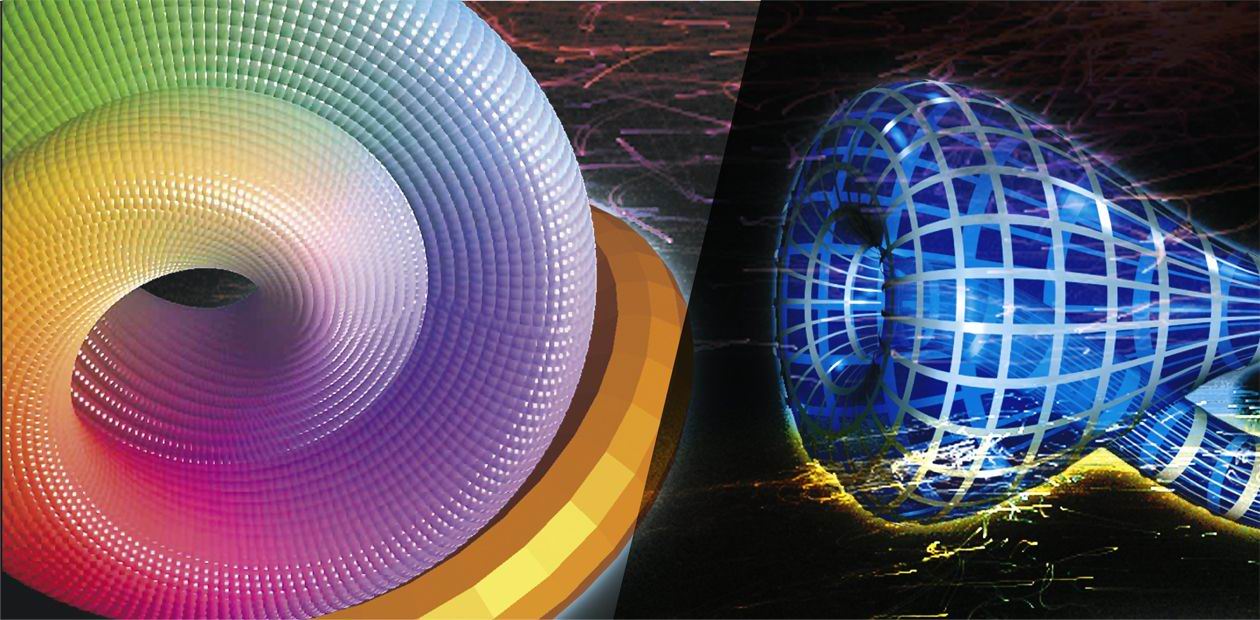

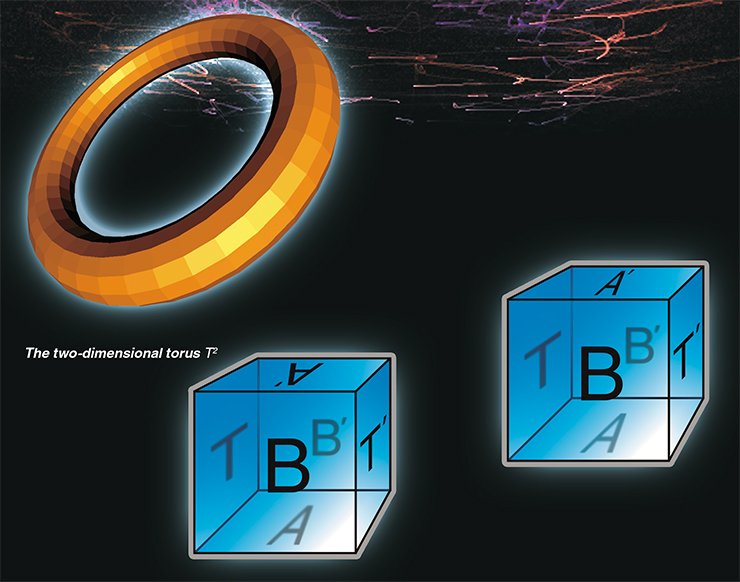

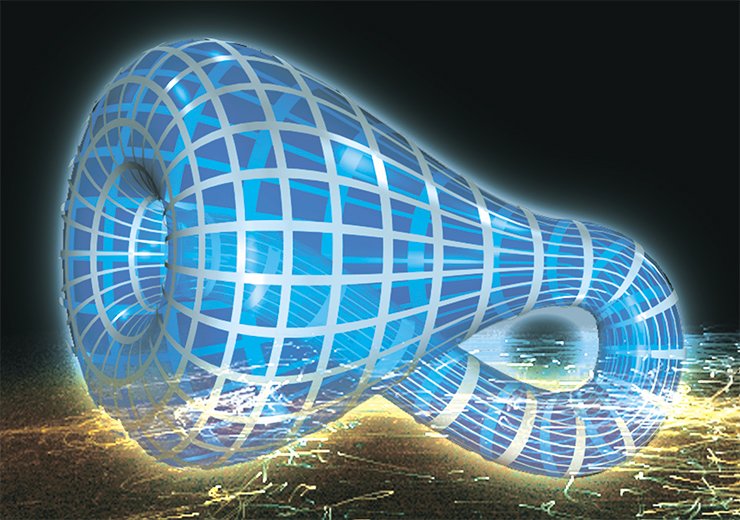

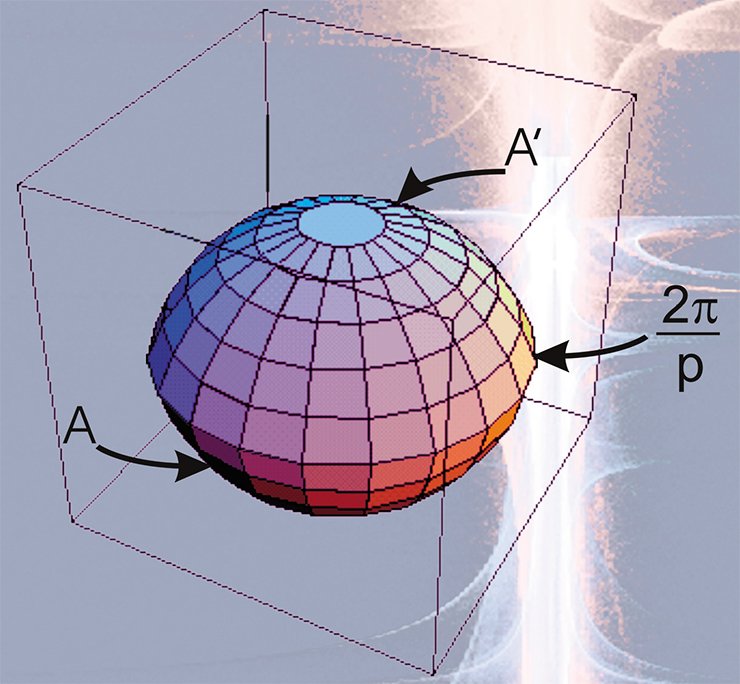

The first and most familiar Euclidean form is a three-dimensional torus, which is a peculiar analogue to a well-known two-dimensional one. Let us denote this set (a cube with pair-wise identified faces) as T3. Another Euclidean form is the so-called twisted torus denoted as Q3, respectively. And now, let us carry out a simple physical experiment to show the difference between T3 and Q3 , both of them being different from the Euclidean space E3.

For that, let us put a spaceship into the center of the face A of a three-dimensional torus and let it move in the vertical direction with the speed of light. Exactly in a year, the spaceship will be back to the starting-point if it continues to move rectilinearly. Now, the starting-point will be located in the center of the face A’, which is identified with the face A. As a result of the experiment we will find out that there exists a closed straight line l, which is one light year long in the three-dimensional torus T3.

Let us make another similar experiment. Let us launch the spaceship at the point y on the face A within 1 km range of its center. In a year, the spaceship will be safely back to the point y. The conclusion of the second experiment: there is a closed straight line passing through the point y,which is one light year long and parallel to the line l.

Now let us make both experiments in the twisted torus Q3. The first experiment gives absolutely the same result as earlier. However in the second case, the result will be completely different. The spacecraft starting at the point y will reach the point z on the face A’ = A ,which is directly contrary to the point y with respect to the center of this face. The flight will continue during one more year and, after that, the spaceship will return to the point y.

Thus in Q3 , there is a closed straight line passing through the point y, which is two light years long and parallel to the line l. Therefore the manifolds T3 and Q3 are different and not equal to the Euclidean space E3, which has no closed straight lines.

The next Euclidean form is the solid Klein bottle (manifold K3) that, unlike previous ones, is non-orientable. Let us prove it. To do this, we will repeat the experiment with the spaceship started at the center of the face A, but let us supply it with a propeller revolving clockwise with constant velocity (if it is observed from the cockpit). Let us assume that the spaceship’s fuel-supply is sufficiently large, and the flight in the straight line l will continue for one more year, then the spacecraft returns to the starting point y. When the spaceship is at the starting-point again, the pilot will be surprised at finding out that the propeller revolves counter-clockwise! (Of course we mean the watch the pilot has forgotten at the starting point). The latter implies that the manifold K3 is non-orientable and hence differs from the earlier obtained Euclidean forms T3 and Q3. To conclude, let us note that the size of the Solar System (its diameter being 124•109 km, approximately) is small in comparison with the sizes of the manifolds constructed above using the unit cube. The Solar System could be placed either inside T3, Q3, K3 or in any other Euclidean form. In this connection, to calculate distances less than one light year, we can use ordinary Euclidean Geometry not suspecting that the space surrounding us could be closed. At the present time, mankind has no spaceships which would be able to fly at the velocity of light. This implies that there is no way to make global experiments like the above-mentioned ones and, finally, to determine which of the Euclidean worlds we live in?

Manifold manifolds

As previously discussed, all the above-mentioned manifolds have the Euclidean geometry. What does it mean and what other geometries exist in addition?

Most familiar and widespread geometries are Euclidean, spherical and hyperbolic. Note that the spherical geometry is sometimes called Riemann geometry and the hyperbolic geometry is often called Lobachevski geometry. In addition, there exist five so-called synthetic geometries in the three-dimensional space.

According to geometrical rules which are valid on wa three-dimensional manifold, we will call it Euclidean, spherical, hyperbolic or synthetic, respectively.

The Euclidean manifolds were already considered. As for the others, more than twenty years ago (in 1978) W. Thurston proved the remarkable theorem:

almost all three-dimensional manifolds are hyperbolic, in other words they obey the laws of the Lobachevski geometry. For this result he was awarded the Fields Medal in 1983 – the most prestigious award for mathematicians.

Spherical manifolds can be both three-dimensional and multi-dimensional (Wolf, 1982). In the space of any dimension there exists a finite number of types of such manifolds. The number of synthetic manifolds is very few (Thurston, 1978; Dunbar, 1981; Thurston 2001) in contrast to the class of hyperbolic manifolds. The latter is extremely large, and its classification has not been completed by now.

Spherical manifolds

All three-dimensional manifolds are orientable. This means that whatever closed trajectory the spaceship with a revolving propeller may fly, when it returns to the starting-point, its propeller will be revolving in the same direction as at the start time.

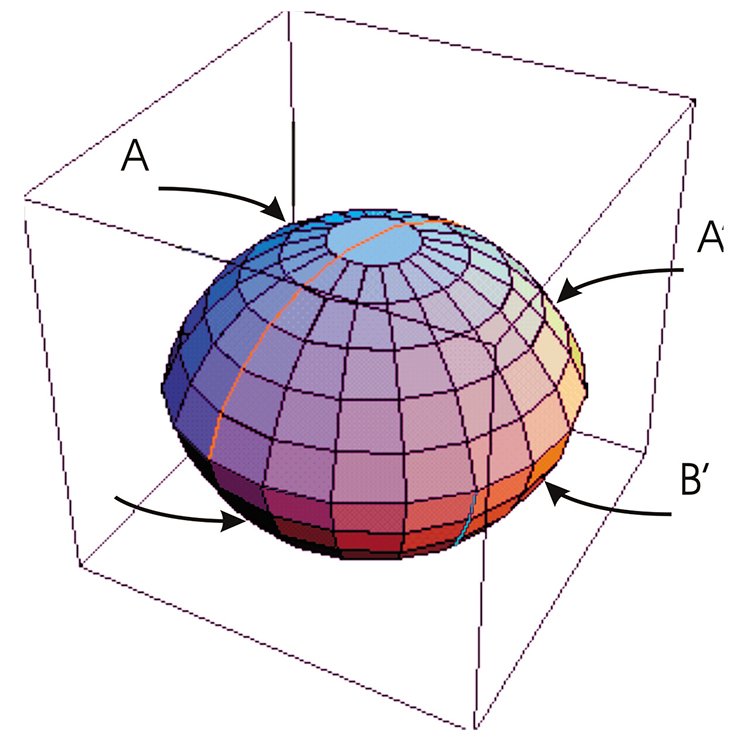

A simple spherical manifold is a three-dimensional sphere S3. It can be defined as the boundary of a four-dimensional ball or, which is the same, as a set of points in the space E4 equally distant from the center. Using a stereographic projection, one can set a one-to-one and bicontinuous correspondence between points of the three-dimensional sphere S3 and points of the set E3 + {∞} obtained by addition to the ordinary Euclidean space E3 of the point at infinity. Thus, one can consider that S3 = E3 + {∞}.

Another example of a spherical manifold is a 3D projective space P3. It can easily be presented as a ball whose diametrically opposite points are identical.

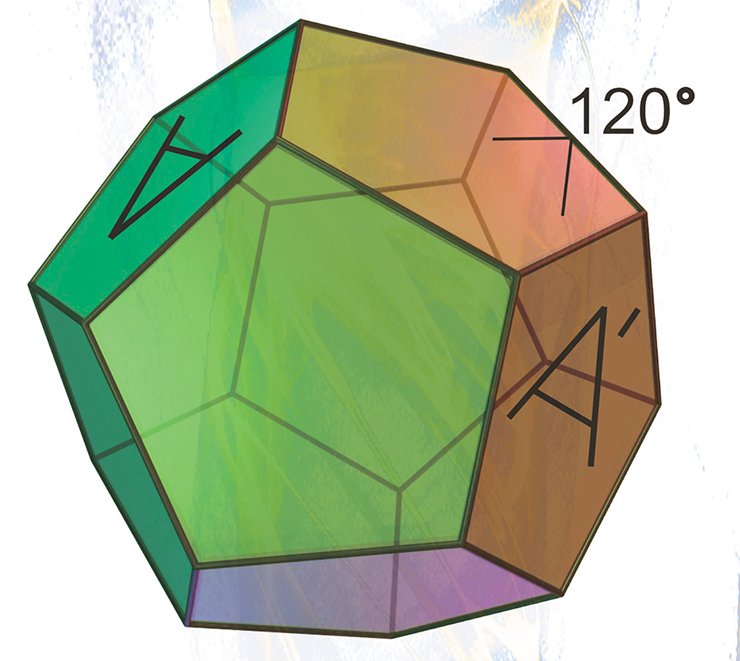

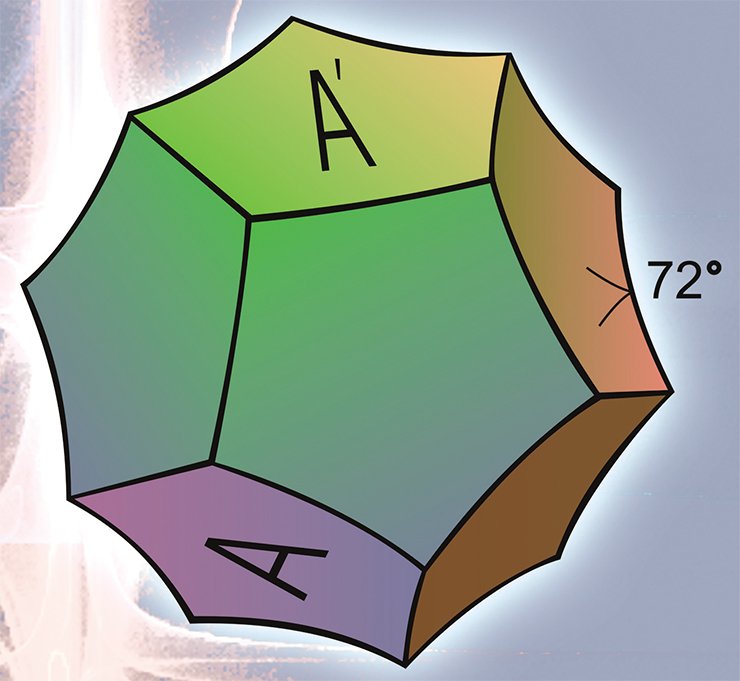

The third and, probably, most non-trivial example of a spherical manifold is spherical Poincar dodecahedron or, for short, the Poincare sphere.

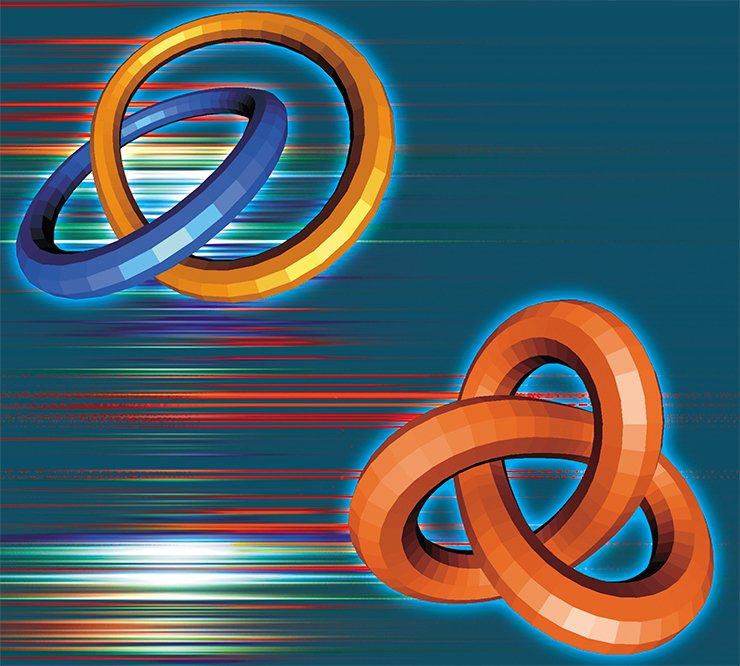

The Poincare sphere is, surprisingly, related to a wide diversity of the fields of mathematics: Geometry, Topology, Group theory, Catastrophe theory, Knot theory and others (Kirbi, Schalermann, 1982).

All other spherical manifolds derivable in a similar way are the so-called lens and prismatic spaces.

Hyperbolic manifolds

The first three-dimensional closed hyperbolic manifold was constructed by F. Loebell, a German mathematician in 1931. However, that construction was sufficiently complicated, therefore two years later H. Seifert K. Weber suggested an elegant structure of a hyperbolic dodecahedron space.

The most difficult part of the construction problem from the mathematical standpoint is to prove the existence of this hyperbolic manifold in the Lobachevski space. A positive reply to this question is given by the fundamental Andreev theorem (1970), which poses necessary and sufficient conditions of the convex hyperbolic polyhedra existence. This theorem is the corner-stone of the modern theory of manifolds founded by W. Thurston.

Constructing manifolds from polyhedrons

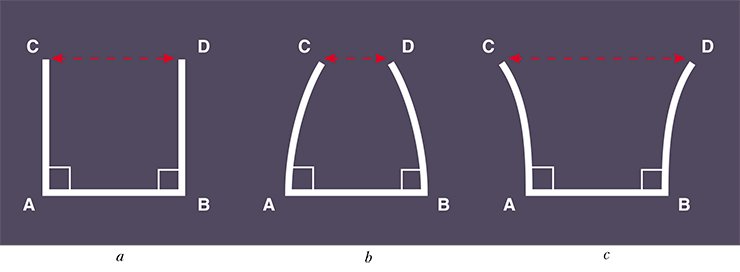

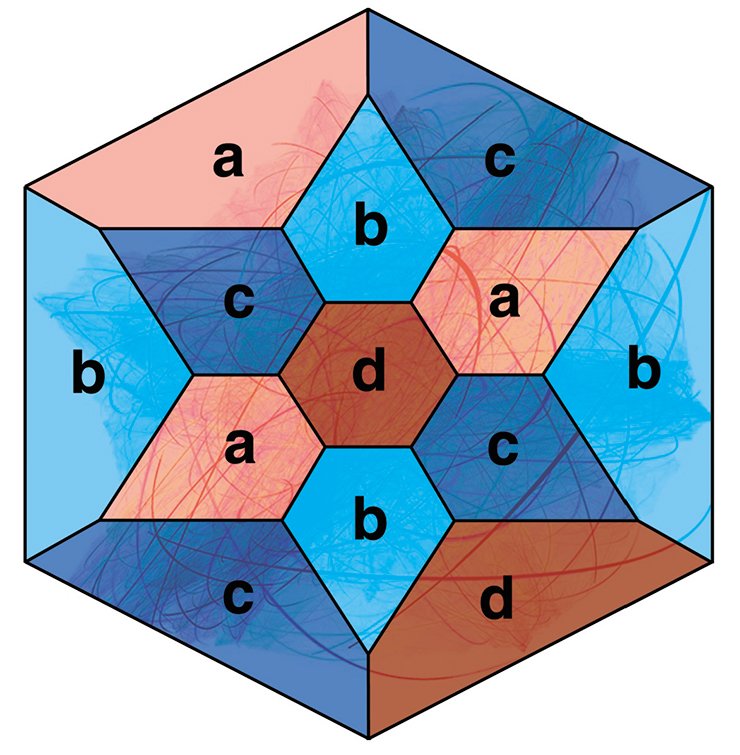

Let us consider the right-angled polyhedron P whose all the dihedral (and plane) angles are equal to 90°. As an example of such a polyhedron in the Euclidean space, one can take a cube, in the spherical space — a tetrahedron, and in the hyperbolic space — hexagonal Loebell prism with twelve pentagons as a lateral surface.

It follows from the Andreev theorem that any polyhedron which has no triangular and quadrangular faces, where at each vertex meet exactly three edges, may be realized as a right-angled polyhedron in the Lobachevski space. Hexagonal Loebell prism obviously satisfies these conditions.

To construct hyperbolic manifolds one can use the following method. First of all, the adjoining faces of the polyhedron should be painted in different colors. Then the corresponding faces painted in the same color should be identified in several copies of the polyhedron. This method of manifolds, construction was first realized by F. Loebell (1931) for a hexagonal prism. Then the method was used by the Japanese mathematician M. Takahashi (1985) for regular rectangular dodecahedron and by A. Yu. Vesnin (1987), for an arbitrary rectangular polyhedron P.

It should be noted that all the manifolds obtained by painting in four colors are orientable. However it was proved that by painting the faces of polyhedron P into five, six or seven colors in similar algorithm one can obtain non-orientable manifolds too (Mednykh, 1992).

Let us dwell on another property of right-angled polyhedron. Let D be a regular right-angled dodecahedron in the Lobachevski space. The spanish mathematician H.-M. Montesinos (1987) proved the following remarkable theorem:

Let us dwell on another property of right-angled polyhedron. Let D be a regular right-angled dodecahedron in the Lobachevski space. The spanish mathematician H.-M. Montesinos (1987) proved the following remarkable theorem:

“Any closed three-dimensional manifold may be obtained from a finite number of copies of polyhedron D by pairwise identifying their faces.”

It should be noted that in the Montesinos theorem, all the faces of identified polyhedrons are congruent and all the edges are of an equal length. At the same time, every edge is surrounded by four, two or one dodecahedron. The first situation may be easily imagined: four dodecahedrons are glued together one after another around a common edge and form a total angle equal to 4•90° = 360°. In the second case, a pair of adjoining faces of one dodecahedron is identified with a pair of adjoining faces of another dodecahedron. The total angle around the edge belonging to both dodecahedrons is equal to 2•90° = 180° in this case. The third variant may be easily created by identifying the adjoining faces of one dodecahedron turning by 90°.

The presence of edges of the second and third types turns the manifold into the manifold with singularity or orbifold. In this case the mentioned edges form a singular set of the orbifold. Let us note that the manifold admits the Lobachevski geometry everywhere except the singular edges.

Three-dimensional orbifolds

Euclidean orbifolds

For any three-dimensional Euclidean orbifold, there exist a basic set — a curvilinear polyhedron from which one can obtain a given orbifold by identifying pairwise its certain faces.

The Borromean rings and a three-dimensional sphere with a singular knot “eight” set may be used as examples of the Euclidean orbifolds.

There are only 230 three-dimensional closed Euclidean orbifols – as many as the crystallographic groups discovered by E. S. Fedorov, a Russian scientist, at the end of the 20th century. The structure of the Euclidean orbifolds was completely described in W. Dunbar’s doctoral thesis which was defended in 1981 at Princeton University — the first-rate centre of mathematics in the world.

Spherical orbifolds

The so-called rational knot or link may be used as a singular set of the spherical orbifolds. This may also be a knotted graph, each vertex of which issues three edges. In particular, the tetrahedron frame (edges + vertices) located in a three-dimensional sphere may be a singular set of the spherical orbifold.

In this connection, it should be borne in mind that strong knotting of a tetrahedron can spoil a spherical geometry and make the orbifold possess the Euclidean, hyperbolic or one of the synthetic geometries.

Recently, a computer program enabling the calculation of the volumes of knotted graphs embedded into a three-dimensional sphere has been developed by the Australians, Prof. K. Hodgson and his student D. Heard (2005). The complete classification of three-dimensional orbifolds in all the geometries except for the hyperbolic one was made in W. Dunbar’s papers. As in the case of manifolds, the hyperbolic geometry is the richest, and a complete description of orbifolds in it has not been obtained until now.

Hyperbolic orbifolds

According to the Montesinos theorem each three-dimensional manifold may be transformed into a hyperbolic orbifold if a singular set is put inside it. Since there exist infinitely many different manifolds, then there are infinitely many hyperbolic orbifolds as well.

According to the Montesinos theorem each three-dimensional manifold may be transformed into a hyperbolic orbifold if a singular set is put inside it. Since there exist infinitely many different manifolds, then there are infinitely many hyperbolic orbifolds as well.

The three-dimensional sphere with the Borromean rings marked with “4” as a singular set is a simple hyperbolic orbifold. Another example is a strongly knotted tetrahedron whose all edges have the singularity index 2. The proof of such a fact is usually sufficiently complicated and may be performed with the help of Geometrization theorems obtained by W. Thurston and his followers. The main idea of the proof is the following: if an orbifold is not Euclidean, spherical or synthetic, and satisfies certain simple geometrical conditions, then it is hyperbolic.

The changes taking place in mathematics for the last one and a half hundred years have not only expanded its contents but have basically modified it. At the present time, the subject of mathematical research includes any structure which may be investigated by logical reasoning and a variety of conclusions. It is not a mathematical problem whether it finds application and prototype in reality.

Physicist’s commentsIt is clear that, in fact, those theories get an advanced stage of development, which find application in mathematics itself and especially beyond its bounds. Although the experience gained in science evolution has shown, a number of times, as abstract theories to find important applications, for the most pure mathematics it does not matter in principle. The originator of the set theory — G. Cantor expressed the creative credo of modern mathematics in apt turn of phrase: “The nature of mathematics… is its freedom.”

References

Vinberg E. B. On non-Euclidean Geometry, Soros Educational Journal, No. 3, 1996, P. 104-109.

Thurston W. P. The Geometry and Topology of Three-Manifolds, Princeton lecture notes, 1980.

Hodgson C., Heard D. Computer program “Orb”, August 2005, http://www.ms.unimelb.edu.au/~snap/orb.html

The picture on cover page taken from http://sprott.physics.wisc.edu

The paper was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grant 06-01-00153) and INTAS (grant 03-01-3663)

The author and the editors express their sincere gratitude to N. V. Abrosimov (Principal Engineer with the Sobolev Institute of Mathematics SB RAS, Predoctoral Researcher at Novosibirsk State University) who has rendered assistance when preparing the publication