Our Neighbors: The Forest Nenets

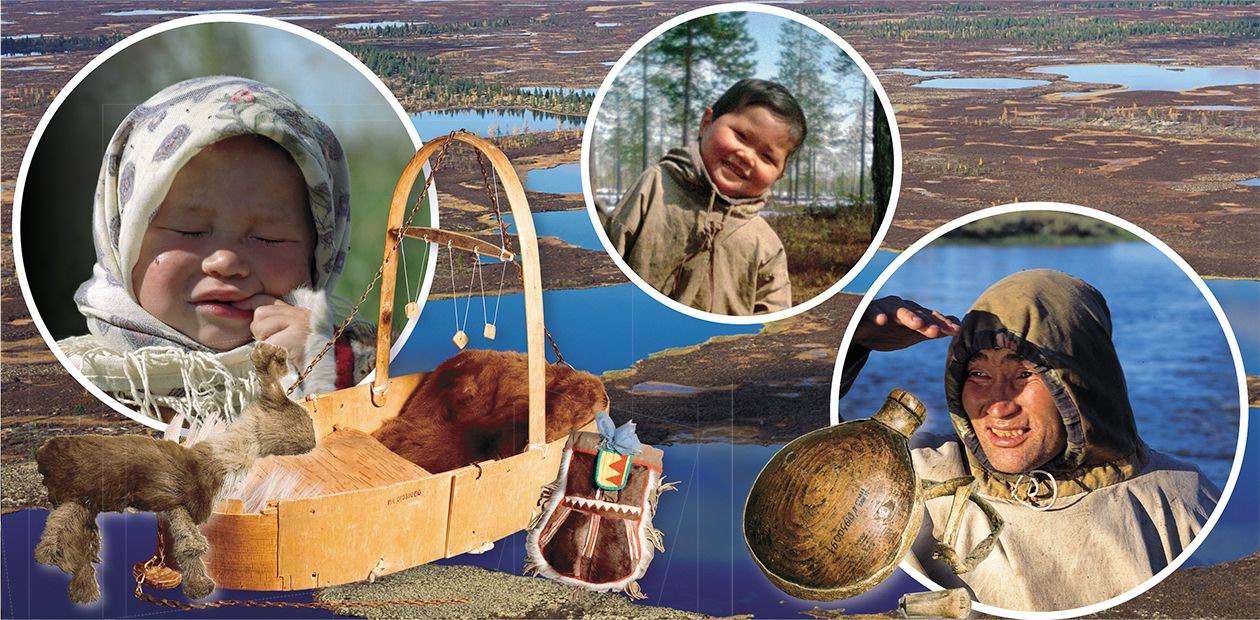

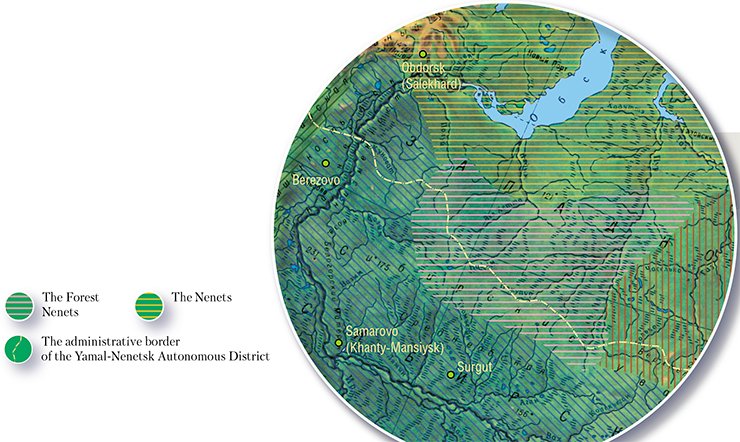

We offer to our readers some chapters from the book The Forest Nenets, which is the result of the long-term project “Our Neighbors: The Forest Nenets”. The aim of the project is to study and preserve the material and spiritual culture of the Forest Nenets, a small ethnic group living in the southern part of the Yamal-Nenetsk Autonomous District (“YNAD”) in the Pur River basin. The project is quite unique because it was carried out by the employees of the Gubkinskiy Museum of North Development jointly with the natives, who still live according to their traditions. The latter documented and described their daily routine life. For this purpose, the Museum donated them tape recorders, video and photo equipment. In this way, the daily routine of Nentsy camps was “self-documented” over several years*

The Nenets are one of the native peoples of Siberia consisting of two groups: the Tundra and the Forest. The Tundra Nenets is the larger group of the Nenets people, engaged mostly in reindeer-herding. The Forest Nenets count no more than 2000 people. They call themselves neshan’ (“man”), nesha is the plural. In 1896, V. Bartenev described them in the following way: “In appearance these people resemble the Samoyeds but they are a little bit more dark-skinned and of a more pronounced Mongolian type; however, their languages display a great difference.” There are two dialects in the Nenets language, the Tundra and the Forest. The writing system was created only for the Tundra dialect, now spoken by 95 % of the Nenets.

The Nenets clan is a group of blood relatives by the male line. Children belong to their father’s clan and take the corresponding name. When married, a woman goes to her husband; a widow either has to or has the right to marry her brother-in-law. The clan members have in their mutual possession a certain area of summer and winter pastures, hunting lands, and clan’s sacred places. Every clan has its own burial site. The borders dividing the areas of families and clans are quite conventional and not documented. In our days, intensive industrial development of the traditional territories of the Forest Nenets is driving many families out of their places, so that they have to resettle in villages or in new lands.

my little teta.

The most longed-for of all children,

the most obedient of all sons,

the most long-legged of all boys,

the most lucky of all hunters.

Let your reindeers be the fastest

on the land of your forefathers

of Dyan clan.

Let your reliable friends be

the husky dog and the reindeer.

Let the tame reindeer come

to the chum before the rest of the reindeers.

Let him bring only the good news to you.”

Lullaby of the Forest Nenets

The native peoples of the North manage their economy so that not all the resources are consumed by the members of their community, but there is something left for their descendants as well. “To take from Nature no more than is needed” is their main principle that we have long forgotten.

Traditional nourishment

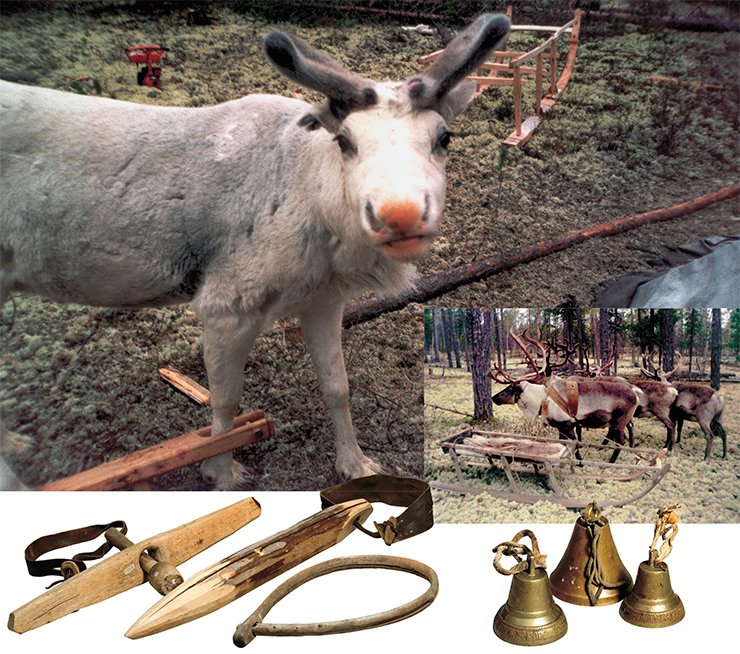

The basic diet of the Forest Nenets consists of reindeer meat, fish, and game. The vitamin C contained in raw meat, reindeer blood, and fish-oil not only prevents them from catching diseases but also makes them more resistant to cold. The reindeer fat, blood, liver, heart, and kidneys are also a source of vitamins and minerals.

Reindeer meat is winter fare. The Nenets almost never eat the riding-reindeer meat, because it is sinewy and contains little fat. They do not eat meat of ill reindeers either, especially if the cause of the illness remains unknown. As the Forest Nenets did not known salt, meat and fish were not salted but dried or smoked. The best delicacy for the Forest Nenets is the meat of a reindeer which has just been killed. They eat raw meat right next to the carcass and wash it down with reindeer blood, which raises hemoglobin. The marrow from the cortical bones of extremities is also eaten raw right there, or frozen—later.

In summer the basic food is fish and game. Meat of wild geese and ducks is quite nutritious. The best piece is geese thigh. Women are forbidden to eat the part of a bird that contains the heart and lungs because, according to the belief, it might bring a disease to them. If there is a lot of game, they smoke it and keep for a longer time. They also collect and eat bird eggs. The Forest Nenets follow the strict rule: They eat only eggs of large birds, leaving a couple of eggs in the nest, so as not to decrease the amount of game during the autumn hunting season. In the autumn, they hunt wood-grouse and black-grouse.

Many authors claim that eating fish and fish products is one of the reasons why northern people are calm and friendly. It is proved that vitamin D and unsaturated fatty acids contained in fish oil directly influence a person’s mood, and their lack can lead to depression. Fish oil also contains physiologically important microelements: iron, manganese, chrome, iodine, copper, molybdenum, nickel, and cobalt.

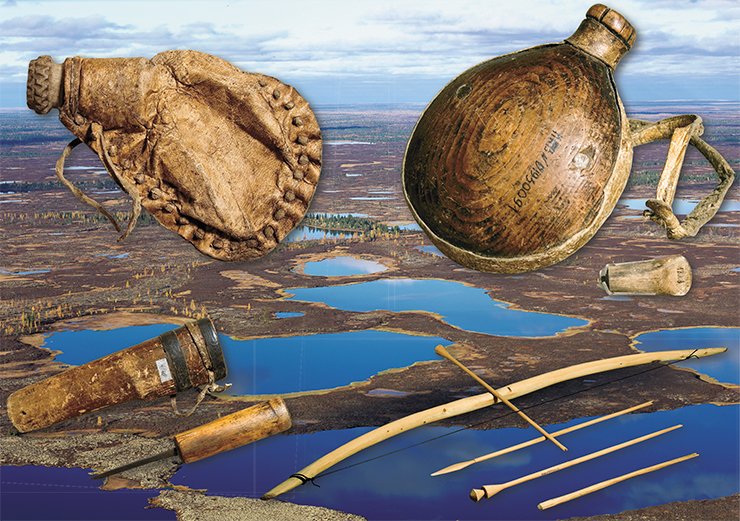

Fresh fish eaten abundantly is valued as a means for strengthening the body. The Forest Nenets also dry and smoke fish, and mill it into fish powder. In winter, the best dainty is stroganina, fine shavings made from frozen fish or reindeer meat. They eat it with their hands and dip it into salt or reindeer blood.

Fresh-killed fish fillet is used to prepare sogudai. The back and belly parts are the most tender and delicious. Bellies of whitefish, believed to be medicinal for digestive system disorders, are given to seriously ill and old people, children, and women before giving birth.

The Forest Nenets eat ide, sturgeon, whitefish, white salmon, pike, and burbot. The latter is eaten only boiled. They believe it to be not quite pure for it sucks other inhabitants of rivers and lakes that died in the nets, thus touching the world of the dead.

The pike occupies a special place. Some clans of the Forest Nenets think it is sacred. A legend told by the Forest Nenets Solu Veisovich Pyak says: Once the brothers of the Pyak clan took their brother Tachu fishing. They caught a lot of fish, and there was a small pike, hardly longer than a finger. Tachu was very happy. He took it in his hands, the fish twitched and nearly fell, but Tachu caught it. The grown-ups began laughing at him and joking, “Tachu, put it in your mouth”. Without hesitation Tachu put it in his mouth. The fish slipped down in the throat.

In the morning Tachu woke up, touched his belly and said, “Mommy, the fish is moving inside of me.” Tachu was growing, and so was the fish in his stomach. When it grew very big, Tachu died. The grown-ups say, “The pike is no toy but a sacred fish. You should not joke about it.”

In some clans only men scale and cook the pike. Women are forbidden to cut and eat this fish. They believe that if a pregnant woman cuts a pike, an evil spirit might come into her womb. Women are also forbidden to eat raw sturgeon, and at a certain time of their period they cannot eat the cooked one either. There are more taboos for the Forest Nenets; for example, they cannot put live fish into boiling water.

The newborns’ basic food is their mothers’ milk. The Forest Nenets nurse for a long time, sometimes up to five years. When the children grow a little, they begin to eat the same food as the adults. They are given the best bits. When the Nenets cut a reindeer, they always give the kidneys to the little ones, for they are tender, and the children eat them with pleasure. Favorite dishes of the Forest Nenets’ children are fish fried on stick; boiled caviar with fresh cowberries; stroganina; hot cakes from a mixture of flour and reindeer blood; and, above all, baked squirrel stomach.

Traditional upbringing

THE CEREMONY OF MEETING A NEWBORN

The Forest Nenets usually celebrate a birthday only once in a lifetime — when the baby arrives in the world. It is a day of great joy for the parents and all the relatives. In the old days, they would invite a shaman to initiate the baby into the world of people and to protect him from the evil spirits. By the shaman’s arrival, the ceremony of purification would have been held.

Now shamans are not invited, for real shamans are very rare. But the ceremony is still practiced in virtually every family. Here is how M. and O. Prikhodko describe it (2002): “The grandmother burned a scrap of beaver fur, some tree mushroom and a branch of wild rosemary; put otter’s bones over the ashes; sprinkled with birch shavings and fumigated Khomani’s cradle, her mother and the bed. Then the grandmother threw a scrap of otter skin and birch buds on the ashes and fumed the chum, Khomani’s father and her two-year-old brother Khomaku.” There are some common rules of the ceremony; nevertheless, each family has its own tradition of carrying it out.

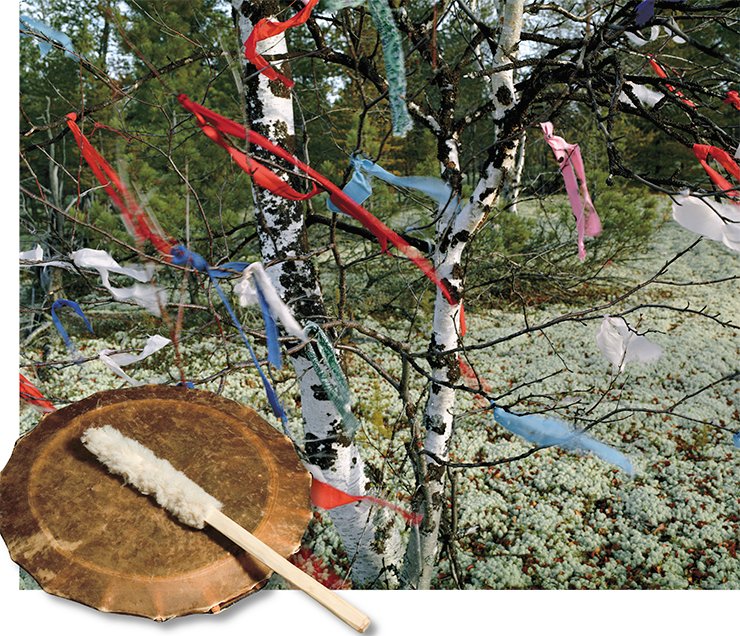

A shaman uses all his knowledge when performing the action called kamlanie. Here is how P. G. Turutina describes the ceremony: “Kamlanie always took place in a Nenets tent chum. Kamlanie could happen at any time of day or night and usually went on for several hours. The invited persons would take their seats, the shaman would sit down on the reindeer skin next to the fire, then he took the mallet and began drumming. He accompanied the strokes with the drawling monotonous calling, “Hov, hov, hov!” Then the sounds of the drum would die away, and the shaman would begin asking the spirits. Sometimes on the contrary, the shaman’s soul would wander in the world of spirits, and then in his singing accompanied by the drum he described his trip to the other world and his meeting with the spirits. Sometimes it happened so that the shaman’s body, left by his soul, fell down and lay motionless until the soul came back.”

On the occasion of a birthday, a young reindeer is killed. The guests, relatives and neighbors, give their presents: a piece of chintz or broadcloth, birch dust for the cradle, matches, a bag of food. The baby’s wealthy relatives, as well as the baby’s father, mother and siblings give the newborn a young reindeer calf each. The mother puts matches into the cradle, for they are said to possess some magic quality: it is believed that they can scare away evil spirits. In the old days, they would put a coal into the cradle and ask the fire to protect the baby from evil spirits.

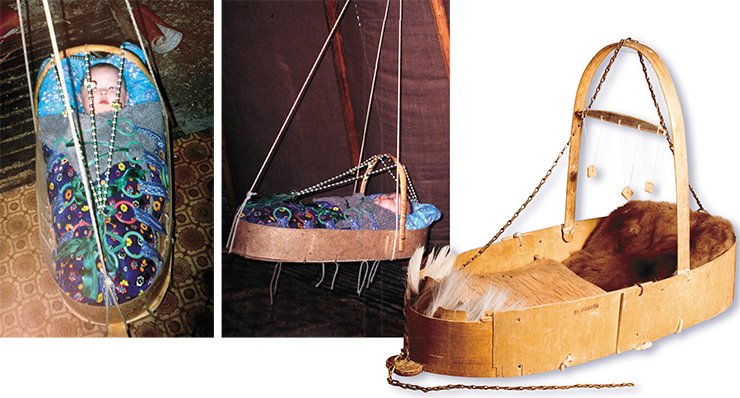

THE CRADLE

A first year of baby’s life is spent in the cradle. The baby sleeps and plays in it, is transported in it when moving on to a new place. Regardless of the number of children in a family, there is usually only one cradle. It is made for the firstborn and is passed on to other babies. When the cradle is worn out, they make a new one; the same happens if a baby dies.

The cradle is one of the most expensive things for the northerners. With the Forest Nenets, the cradle is made by men. It is oval-shaped and has a flat bottom. As a rule, they used to make it out of birch, but with the advent of new materials they make it out of plywood. On the inside, the bottom is equipped with special belts that help to hold the baby. It is very convenient for the mother: She can tend to the house without worrying that the baby can fall out or nurse the baby without taking it out. The Forest Nenets pay very much attention to the decoration of the cradle. For this purpose they use beads, broadcloth, metal buttons, and other things.

Before the modern means of keeping the baby clean appeared, they used to put a baby inside a reindeer calf’s skin enveloping its legs. A special scoop made out of birch bark was placed on the skin and filled with birch dust, which saturated moisture and served as an oil-cloth. This was covered with a piece of long and heavy fur cut from the reindeer’s neck, which substituted for a diaper. As it got dirty, a clean one was put in. Today the Forest Nenets use diapers, quilts, and special clothes for the newborn.

Cradles of the Forest Nenets are perfectly fit for the nomadic way of life. Light and durable, they are easy to transport in a boat, and to tie to a chum pole or to a tree branch. If the baby is sleeping, it is covered with a shawl to protect it from the light, gnats, and noise. When transporting the baby in winter, they place the cradle in a fur case made of reindeer skins or in a quilt. It fully covers the cradle, leaving only a small hole for breathing; and the baby feels warm and cozy even outdoors.

Children’s clothing

All children, boys or girls, wear the same clothes. These are fur clothes that resemble clothes for the adults. Mittens are sewn to the sleeves so that they make a single whole together; bells are sewn to the inside of the sleeves, which helps the mother to know where her child is.

Summer children’s clothes are made of chamois, reindeer skin without pile; and winter clothes are made of reindeer fur. Children’s garments resemble those of the adults, but their designs are simpler: hare ears, heads, and the like. Traditionally, they use for sewing threads made of reindeer sinew, for they are much more durable than the factory-made. To make the clothes warmer, they try to make as few seams as possible. A narrow ribbon of broadcloth or a long hair from reindeer’s neck is put between the pieces of fur to make the seam thicker.

Today the Forest Nenets wear both national and modern clothes. They are frequently handed down from older children to younger ones. Every child has a holiday garment, which they put on when visiting someone or going on a long journey.

Name-giving principles

When a baby is born, the Forest Nenets give it a name, but they do not use this name in everyday life replacing it by a nickname (“kid name”), which they use until the child is fifteen. G. M. Katkileva, a Forest Nenets, says: “My Nenets name is Umy, which means ‘kiss’. My older brother called me that. My mother was chopping firewood in the yard, and my brother said, ‘I keep kissing her, and she keeps crying.’ So I was called Umy. I was registered as Galina later.” The nickname can indicate where the baby was born; whether it was the first, or second, or other in the family; if it was longed for; what kind of hopes are set on it.

As a rule, real Nenets names are never repeated. Every child is given a new name, because the name of the dead is not supposed to be uttered. If two people share a name, and one of them dies, the other changes the name. At the same time, we have data that the Forest Nenets used to give names honoring the grandfather in the father’s line.

Names are not used to call adult people. When communicating, the Forest Nenets use the terms of relation: mother, brother, father, etc. The Russian culture and contacts with the Russian population have influenced the tradition of name-giving. The Forest Nenets began using Russian names, while keeping their clan surnames, for example, Valery Pyak, Roman Vello, Roman Ayvasedo.

Traditions of upbringing and rules of behavior

It is usually mothers who are in charge of their children until the latter reach the age of five to seven; if children lose their parents, they are brought up by their grandfather, grandmother, or other relatives. From two years of age, children wake up in the morning with the rest of the family, wash, have breakfast together, and then play with their siblings next to their chum. Forest Nenets children are very hard-working. They help their parents to store up firewood for the hearth and snow for drinking water, to stoke the stove and wash the dishes. They are responsible for making a stock of berries for the winter. When the berries are ripe, children take some food with them and go to the forest for a whole day.

From the day of birth, children are brought up in two separate “schools”, male and female, for work is strictly divided between men and women: men fish, hunt and herd reindeers; and women do housekeeping, build and put in order their chums, store up the firewood, cook, sew and take care of the children.

The principal teacher for a girl is her mother. From about three years of age, the daughter helps her mother to make beds, wash the dishes, scale the fish, pluck the game. She is still very young when she begins sewing. When she is about six, the girl gets her needlework bag, in which she keeps everything necessary for sewing. She is taught to take care of the needles: they tell her that if she loses a needle, she would have nothing to sew with, and it is impossible to purchase a needle in the tundra. If there is a grandmother in the family, the granddaughter sews a needle-case for her, then a bag for ritual accessories. So the girl not only learns to sew but also to take care of the other members of the family. As a rule, when the little mistress is ten or eleven years old, she can tailor and sew clothes for her dolls; and when she is fourteen, she is able to make large items, mend mittens or hats. At the age of eight, the girl can lead a string of cargo sledges or mind her younger siblings.

The boys try to imitate the adults in everything. When they are five, they keep around their fathers. Watching their work, they learn how to braid a lasso, carve a wooden sheath, bend sledge skids. From seven years of age, under the guidance of their fathers and older brothers, boys learn to plane, saw, chop, and ride reindeers. Contacts with reindeer foster in the children love for the animals, ignite interest in reindeer herding. The adults teach the children to take care of the calves who were born weak or lost their mothers right after birth. At first, little reindeers live in the chum, sleeping next to their little master, who takes care of them and feeds them. Even when they grow up, the tame reindeers stay around the chum and people and willingly play with children. The Forest Nenets children adore dogs, who are practically family members.

From an early age on, the Forest Nenets teach their children to be friendly towards one another, instill such qualities in them as generosity, amiability, and hospitality. Little guests are presented things or toys of their peers, if the owner permits. In everyday life, the Forest Nenets follow a lot of rules of politeness.

The children are taught to express their gratitude with their actions. For example, if you are treated with some delicacy, it is impolite to return the bowl empty, you have to put something delicious in it, too.

The Forest Nenets respect food and they have certain rules of treating foodstuff. For example, it is forbidden to laugh at food and to eat up after the old people lest you fall ill. Boys are not supposed to wash dishes, or they may turn out to be bad hunters — all the birds and beasts would hear the scratch of the dishes from afar.

It took centuries to form ethic rules for contacts between the relatives. Basic ones are respect for the older and care for the younger. The Forest Nenets, as other Northern people, do not object to their parents, even if they are wrong. With particular respect children treat their father as the principal bread-winner of the family. Adults also respect their children. For example, it is unacceptable to raise one’s voice or, worse, to lay one’s hand on a child.

Relationships between the people and their environment, and people’s behavior in the taiga are governed, to a great extent, by the old principles of sin — taboos. Parents explain that it is a sin to dig out earthworms, destroy birds’ nests, break tree branches, litter in the forest, because God can punish the guilty party. It is explained to the children that it is forbidden to spit in the water, earth and fire, for each of them has a face. You cannot put a sharp object into the soil, because you will then poke the Earth in the eye. It is forbidden to wave a knife or an axe without need, for it can offend the forest spirit.

From an early age, the children are taught that it is bad to steal, to be greedy, to offend orphans, to cheat, to complain, to boast, to have bad thoughts in mind, to scatter things in the chum, to throw them in the forest, to eat outdoors. They are forbidden to make noise in the presence of adults. The children know this rule very well, and when guests come, they go outside and play. Usually, the adults interfere in children’s games and conflicts only when the matter gets out of hand. Then the children are moved apart, but the ringleaders are not scolded. As a rule, there are no telltales among Northern children: everybody is responsible for his or her own faults.

Children’s games and toys

Games are an important step in the child’s development, they help the child to learn things about the world. In their games, children do not just mimic grown-ups, they unconsciously prepare themselves for an independent life. Future hunters and reindeer herders need practical skills, and they get them through games.

The boys’ toys and games can be divided into four groups: common, hunting, herding, and fishing. One of the favorite games is lasso throwing. Competing in their adroitness, boys are trying to throw the lasso loop over the sledges head or reindeer antlers lying on the earth. Imitating the adults, children jump over small sledges, harness dogs and ride dogs’ relays. In their games, children often use animal skins, hare paws, reindeer antlers, bird wings and claws: the children attach them to their clothes, pretending to be this or that animal. But the adults do not allow their children to play with the skin, bones or teeth of a bear, for it is a respected animal.

Playing “hunters” is very widespread among boys. Boys’ toys include real traps, parts of traps and some other hunters’ accessories that help the children to learn to hunt. A father makes the first bow for his son; and when a boy turns six or seven, he can make a bow and arrows by himself. Toy arrows are lighter and shorter than the real ones, but you can shoot them. As a child grows, the bow is several times readjusted and made more complicated; it becomes a real weapon, with which small animals and birds can be hunted.

The girls play their own games. Their toys include dolls, dolls’ clothes and dolls’ household. In old days, the dolls’ heads were made of the beaks of waterfowl, because it was believed that migrating birds each year go to God and return pure and innocent. The clothing for them was made out of scraps of colored fabric and fur. The dolls did not have faces, hands and feet, that is, nothing that could identify them with humans. They believed that a human face and body could inanimate, humanize the doll. In old days, children were forbidden to play with things possessing supernatural power. Today the custom has lost its validity, and Nenets girls play both with traditional and factory-made dolls, but they dress them in the same way as before.

Some women-dolls have baby-dolls in cradles. A doll usually has a toy chum, sledges and reindeers. Girls make whole doll families. The first world built by a person, in which she distributes the roles, is the doll world. The dolls are regarded with a certain degree of superstition. They believe that the life of the doll determines the fate of its mistress.

The children like very much to build a small chum outside the big one and play in it all day. It has floor planks, dishes, beds — everything like in the real one. For the night the toy chum is deconstructed, because the Forest Nenets believe that it can be inhabited by evil spirits.

In their games, children represent real life episodes. The adults, watching them, softly correct their actions and instill in them rules of behavior appropriate to the generally accepted norms of ethics. Children games, in spite of their simplicity, fulfil the important ritual functions of keeping traditions alive and preparing children to their future family life and work.

The photos are by A. Marinichev. Some of the objects depicted belong to the Gubkinskiy Museum of North Development. A number of the photos were obtained in the process of “self-documenting” of the Forest Nenets

* The project was financially supported by the President of the Russian Federation; Otkrytoe Obshchestvo Institution; Tyumen Oblast Duma; Yamal-Nenetsk Autonomous District Administration; Department of Culture, Arts and Cinematography of YNAD Administration; Gubkinskiy Administration; OAO NK Rosneft-Purneftegaz Public Corporation; Gubkinskiy Union of Businessmen; OOO Geoilbent Ltd.; and ZAO Grant