WANGFUJING: A Story of One Street

What is a street? It is a passage between two rows of buildings for walking or driving through – an academic dictionary is, as always, laconic. While most of the streets are just ordinary ones, some deserve to be written with a capital ‘S’. Broadway in New York and Arbat in Moscow, Champs Elysees in Paris and Deribasovskaya in Odessa, Nevsky Prospekt in St. Petersburg, Khreshchatyk in Kiev, Piccadilly in London…

The list of great streets in the most famous and visited cities around the world strikes imagination, and so do their appearances, which differ as much as the faces and languages of the tourists who are filling them. But all these streets have one thing in common – being a quintessence of national spirit, they are essentially cosmopolitan and serve as global “crossroads,” where people of different nationalities and cultures can get to know one another better and feel themselves to be part of a single humanity.

An exploration now awaits the reader, a guided tour of the past and present of Wangfujing, the most ancient and famous trading street in Beijing, a face-to-face meeting spot for tradition and modernity, for the mysterious East and the pragmatic West. And the role of the guides is assumed by Novosibirsk academics, who have repeatedly shared on the pages of our magazine their travel impressions of China, our great neighbor with a history of more than three thousand years

Au soleil, sous la pluie,

à midi ou à minuit.

Il y a tout ce que vous voulez...

Pierre Delanoe

In the life of every – well, almost every – city, there is one main street. In many American settlements, people call it, without further ado: Main Street. However, in big cities with a rich past, such a street bears its own unique name.

Of course, these cities (which are not necessarily giant metropolises) have many other famous streets, squares, and avenues. But the street that is deep in your heart and in depths of your soul – this street can only be one. Together with the adjacent quarters, it becomes a symbol of the city, displaying its most conspicuous features. This is why you can only say the name of the street: Broadway, or Ginza, or Unter den Linden, or Champs Elysées (aloha from Joe Dassin!), and you no longer have to mention the city they represent.

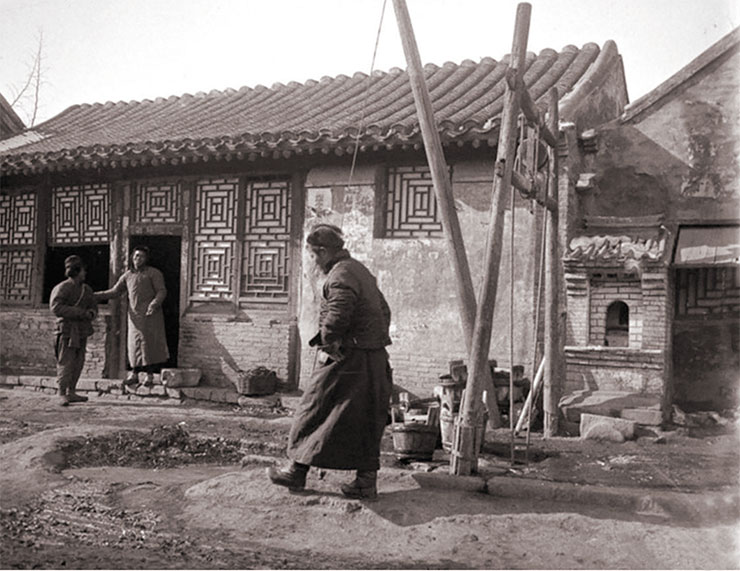

Just yesterday, Wangfujing Street derived its special flavor from hutongs, the narrow lanes branching off the street. The hutongs were formed by the rectangles of traditional Chinese mansions siheyuan, consisting of squat one-story buildings around a courtyard. According to the old canons, the mansions inside the quarter were oriented to the cardinal points, and the streets stretched from west to east. A sophisticated mixture of aromas, especially noticeable on hot summer days, was oozing to the street through these passages: cooked food with various herbs and spices, mixing with the stench of ancient underground communications. When spontaneous construction began in the first half of the last century, the once relatively orderly neighborhoods turned into a kind of labyrinth. Now the hutongs are being vigorously demolished (or, more precisely, carefully dismantled), and new modern buildings are being erected on the vacated sites

Just yesterday, Wangfujing Street derived its special flavor from hutongs, the narrow lanes branching off the street. The hutongs were formed by the rectangles of traditional Chinese mansions siheyuan, consisting of squat one-story buildings around a courtyard. According to the old canons, the mansions inside the quarter were oriented to the cardinal points, and the streets stretched from west to east. A sophisticated mixture of aromas, especially noticeable on hot summer days, was oozing to the street through these passages: cooked food with various herbs and spices, mixing with the stench of ancient underground communications. When spontaneous construction began in the first half of the last century, the once relatively orderly neighborhoods turned into a kind of labyrinth. Now the hutongs are being vigorously demolished (or, more precisely, carefully dismantled), and new modern buildings are being erected on the vacated sites

In Beijing, too, there is such a street. It is located in the historical center, stretching in compliance with the ancient urban planning principles along a strict line North–South. For a long time, Wangfujing Street was the main trade thoroughfare of the Chinese capital. Currently, its commercial superiority has been overtaken by other areas (e. g., Xidan). Nevertheless, Wangfujing remains one of the main attractions for both local and foreign tourists. But first things first.

Prehistoric McDonalds becomes a museum

It is best to start exploring Wangfujing from its origins – both topographically and chronologically.

In 1996, during a large-scale reconstruction of buildings near the southern end of the street, which abuts against the arterial Chang’an Avenue, construction workers discovered stone and bone tools. Excavations lasting for six months revealed the remains of an Upper Paleolithic site (dated to about 24,000 years ago), probably a temporary hunting camp, where ancient humans used to butcher prey and cure hides. Among the extensive osteological material, researchers were able to identify bones of the aurochs, sika deer, ostrich, Cape hare, pheasant, and various fish. Curiously enough, the place where ancient hunters roasted game meat over bonfires was discovered under the foundation of Beijing’s first McDonalds, which was moved afterwards a couple of hundred meters down the street.

Wangfujing’s national flavor comes from rectangular painted arches on red carved stone pillars under tiled roofs, which you see at the entrance of hotels and marketplaces. These structures, which serve as “sacred gates,” stand at the beginning of some streets in the old capitals of China, in front of temple complexes, and on the Spirit Road leading to the imperial tombs…

Wangfujing’s national flavor comes from rectangular painted arches on red carved stone pillars under tiled roofs, which you see at the entrance of hotels and marketplaces. These structures, which serve as “sacred gates,” stand at the beginning of some streets in the old capitals of China, in front of temple complexes, and on the Spirit Road leading to the imperial tombs…

A set of flint tools (scrapers, piercers, etc.), as well as bone implements (also scrapers, points, burins), was found at the site. Some items had traces of hematite powder. Chinese archaeologists identified two cultural horizons, which, in their opinion, might suggest a relatively long use of the site. However, the period of this use could not have been too long since the inventory did not change over time.

In the northern part of modern Wangfujing, open for driving, you see swiftly maneuvering multicolored taxis, scooters, and light three-wheeled wagons of the most bizarre designs. These motor rickshaws have picked up the baton from their predecessors, which employed human muscle or horses. All these vehicles are equipped with electric engines, even those ones whose youth fell on the middle of the last century. The pedals of the mechanisms spin as if by themselves, and it is only the battery box that gives out the secret

In the northern part of modern Wangfujing, open for driving, you see swiftly maneuvering multicolored taxis, scooters, and light three-wheeled wagons of the most bizarre designs. These motor rickshaws have picked up the baton from their predecessors, which employed human muscle or horses. All these vehicles are equipped with electric engines, even those ones whose youth fell on the middle of the last century. The pedals of the mechanisms spin as if by themselves, and it is only the battery box that gives out the secret

The archaeological site was museumified. Today, everyone who goes out the Wangfujing subway station can start one's tour by visiting a small museum located in the underground floor of the majestic building Oriental Plaza. There, under a glass cover, one can see the partially preserved excavation site with traces of bonfires and accumulations of bones and stone artifacts, complemented by colorful panels showing reconstructions of camp inhabitants’ life.

Many guidebooks and popular editions quite seriously refer to these Paleolithic hunters as “the first Beijingers” despite the fact that this term can only be used figuratively, in quotation marks, since at that time, not only Beijing (and, hence, Beijingers) but even China and Chinese did not exist yet.

“Sweet” water from the jing well

The beginning of the real history of the great city dates back to the Warring States period (5th to 3rd centuries BCE) and is associated with the Lower Capital (Xiadu) of the Yan State. The city’s status had been repeatedly changing over the course of almost 2,500 years, rising to prosperity and then falling into complete oblivion, until it finally stabilized under the rule of the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties. New city walls were erected, and inside them – the Forbidden City (Imperial Palace), which became the foundation for further urban development.

This era marks the beginning of the history of Wangfujing Street. Its name is associated with historical evidence that during the reign of the Ming dynasties, ten princes (wang) built here, near the emperor’s palace, their own mansions (fu), after which the street was called Shiwangfujie, which means “a street of ten wang mansions.” The common folk soon shortened the street name to simply Wangfujie.

Four decorative posts connected by a chain form a fence around a metal lid with relief figures of scaly dragons. This marks the place of an old well, which was assigned the role of the legendary source of “sweet water.” Well, at least tourists have a historical landmark where they can take a selfie

Four decorative posts connected by a chain form a fence around a metal lid with relief figures of scaly dragons. This marks the place of an old well, which was assigned the role of the legendary source of “sweet water.” Well, at least tourists have a historical landmark where they can take a selfie

In the meantime, a spring with pure and “sweet” water was discovered here while digging a well (jing). The water was perfect for refreshment and for quenching thirst, which is why the well stood out favorably from the other ones with their bitterish moisture more suitable for household purposes. The fame of the pure water spring was reflected in the street name, which turned into Wangfujing, which could be interpreted as “a well among the rulers’ mansions.” The water source made this area popular and attractive; plenty of people were gathering here, making it possible to buy or exchange goods with profit.

However, no one could have cancelled the natural cycles of fluctuations in the groundwater level. Apparently, during a new period of climatic minima, the source grew depleted. Furthermore, there were always enough people who wished to draw the famous “sweet” water in Beijing with its formidable number of residents, difficult to envision at any time in the city’s history. Over time the well dwindled in value and got lost among the numerous other hydraulic structures; then it physically vanished, having turned into an urban legend.

In 1992, an old well was discovered during reconstruction works. In the absence of other wells, it was “assigned” the role of the very historical landmark that gave the street its name. A corresponding stylized inscription was made on the cast-iron lid, which most tourists, without looking too closely at the hieroglyphs, take for a genuine Qing monument.

Dong’an: a prototype of modern shopping malls

At the beginning of the rule of the Qing Dynasty, eight corps of Manchu troops were located within the Inner City. Common folk had nothing to do here, and the settlement of outsiders was not welcomed. Therefore, the trade in Wangfujing was sluggish. However, the situation changed markedly towards the end of the Manchu rule, when the embassy quarter expanded, and trade bans became less strict.

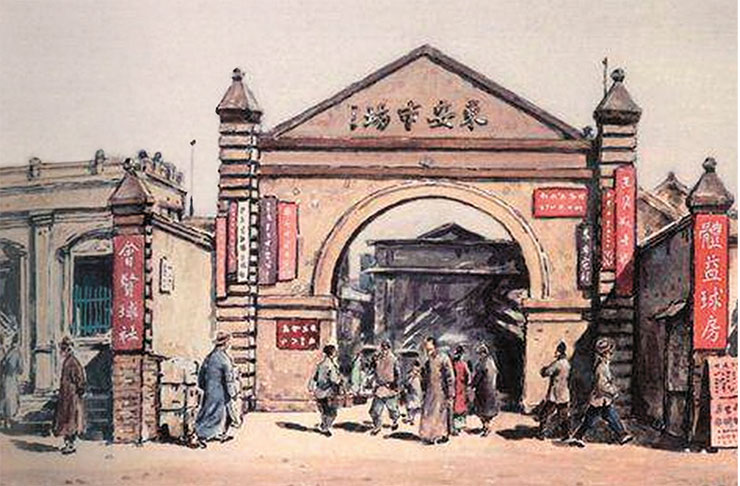

The year 1903 marks the opening of the Dong’an Market, which was named after the relatively close Gate of Heavenly Peace (Dong’anmen), through which one could enter the Forbidden City. Dong’an became the capital’s first universal market, a prototype of modern shopping malls, which offer a great variety of goods and services. Everything was on sale: food, clothes, carts and wagons, hardware, household goods, and lots of other things.

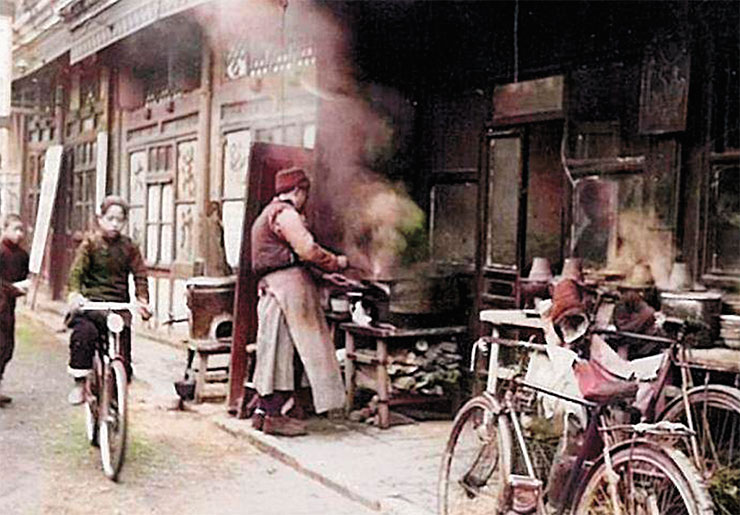

Stalls and kiosks along Wangfujing Street would use every opportunity to grow in number. Street vendors and all sorts of peddlers, coupled with the crowds of loud bargaining buyers – a flea market we know so well – were methodically squeezing the roadway. The market element, indomitably spreading along Wangfujing, became a serious obstacle to the wheeled carriages of the emperor’s associates and officials hurrying to the court. The goal to set in order the street market in Wangfujing became a headache for the city authorities, who had to take a decisive step to achieve it. To do so, they sacrificed the military parade ground used for training of the city’s “squad of miraculous mechanisms,” a military unit equipped with modern weapons

Stalls and kiosks along Wangfujing Street would use every opportunity to grow in number. Street vendors and all sorts of peddlers, coupled with the crowds of loud bargaining buyers – a flea market we know so well – were methodically squeezing the roadway. The market element, indomitably spreading along Wangfujing, became a serious obstacle to the wheeled carriages of the emperor’s associates and officials hurrying to the court. The goal to set in order the street market in Wangfujing became a headache for the city authorities, who had to take a decisive step to achieve it. To do so, they sacrificed the military parade ground used for training of the city’s “squad of miraculous mechanisms,” a military unit equipped with modern weapons

Initially, one would carry on trade in the first half of the day only, after which one would fold up the stalls and kiosks. But three years later, enterprising businessmen opened a tea house, cafe, billiards, and a theater with dance performances. The market teemed with life, seethed with passions, and longed for expansion, spilling periodically out into the street.

In 1912, during the Xinhai Revolution, which put an end to the last imperial dynasty in China, the inevitable thing happened – a horrific fire broke out, being caused by the rebellious troops. As a result of the fire, the market almost perished. However, it not only quickly revived but also managed to expand into the adjacent lands. Such an expansion happened more than once. Regimes changed, from an empire to a people’s republic, but the market continued to work and grow. A marker of its popularity is that old Chinese language textbooks always contained topics about going shopping not just anywhere but precisely to Dong’an.

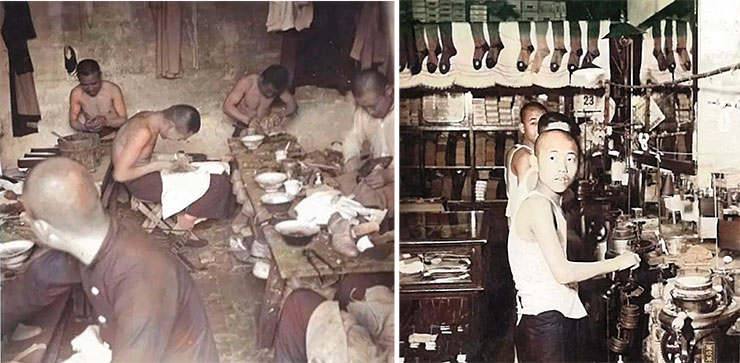

In the late 1980s, one of the authors of this article had the opportunity to visit several times the famous market, a mixture of a noisy oriental bazaar and an even noisier flea market. It could rightly have been called the “Belly of Beijing,” had it not been for the numerous kiosks and workshops (apart from food stalls) offering at very affordable prices the most diverse merchandise, which the sellers sometimes laid out simply on the ground. Therefore, it was constantly overcrowded with customers – until 1991, when Beijing’s Les Halles was closed due to hoarded sanitary and transport issues, just like its analogue in Paris was closed twenty years ago.

The former market was replaced by a huge – as large as an entire residential district – complex of buildings, which consists of boutiques and luxury housing. Persistent rumors were circulating that in order to obtain a contract for this object, Hong Kong developers gave a large bribe to the top Beijing officials, who were then arrested and convicted, some even sentenced to death. That was the end of one of the first anticorruption processes in the People’s Republic of China, which enjoy the unwavering support of the population.

Despite all the scandals, in 1997 the complex was completed and even received the highest national award in civil engineering named after Lu Ban (507–444 BCE), a legendary carpenter and inventor in Ancient China, the divine patron of builders and construction workers. The complex hosts two large department stores officially called the Dong’an Market (Dong’an Shichang) and Dong’an New Market (Xin Dong’an Shichang).

In 2000, a “street of old Beijing” was opened in the underground tier of the Dong’an New Market. This “street” is a kind of interactive museum with buildings that imitate shops and taverns of the Qing times, where one can taste various dishes of the traditional Chinese cuisine – not only the popular Shandong cuisine (lu cai) but also the super-spicy Sichuan (chuan cai) or Hunan (xiang cai), the personal favorite of Chairman Mao. However, the story about the culinary virtues of Wangfujing is yet to come.

In New China

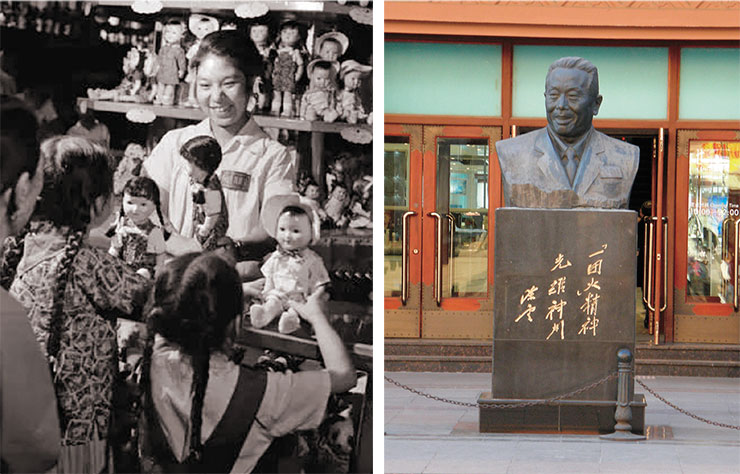

In 1955, the Wangfujing Department Store (renamed into Beijing City Department Store in 1967) was opened on the west side of the street. One would call the new shopping center the “flagship store of New China.” It was located virtually opposite the Dong’an market, which could have been interpreted as a symbol of confrontation between state and private trade, with the former clearly taking precedence.

The Wangfujing Department Store, which was built opposite the Dong’an Market and later renamed the Beijing City Department Store, was intended to meet the needs of working people and was very affordable in terms of prices. However, judging by the cars parked at its entrance, it was also popular among the Chinese officials. Now the department store is a conglomeration of luxury boutiques, whose merchandise pleases the eye but not the purse. The area before the building and its front side are vigorously used for advertising goods and for the periodically changing fantasy or festive installations designed to lure potential buyers

The Wangfujing Department Store, which was built opposite the Dong’an Market and later renamed the Beijing City Department Store, was intended to meet the needs of working people and was very affordable in terms of prices. However, judging by the cars parked at its entrance, it was also popular among the Chinese officials. Now the department store is a conglomeration of luxury boutiques, whose merchandise pleases the eye but not the purse. The area before the building and its front side are vigorously used for advertising goods and for the periodically changing fantasy or festive installations designed to lure potential buyers

Up until the early 2000s, this shopping center could rightfully have been called a people’s department store since it offered goods of acceptable quality at affordable prices. An ordinary salesman Zhang Binggui (1918–1987) became the face of the Wangfujing Department Store. Zhang Binggui was distinguished for his special attitude towards customers, for which he was awarded a bronze bust on the square in front of the department store, where he had worked all his life. (Strictly speaking, Comrade Zhang was not exactly an ordinary employee since, as a foremost worker, he was twice elected a member of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress although he did not hold any administrative posts.)

However, about 15–20 years ago, this “flagship” too allowed itself to be carried away by the force of market elements, surrendering its counters to expensive elite goods. For those who sigh over the memories of the old days, since 2019 they have on the second underground tier of the department store a functional replica of the shopping street 30 years ago. Those wishing to experience the democratic atmosphere of the early 1980s can fulfill their desire, albeit at modern prices.

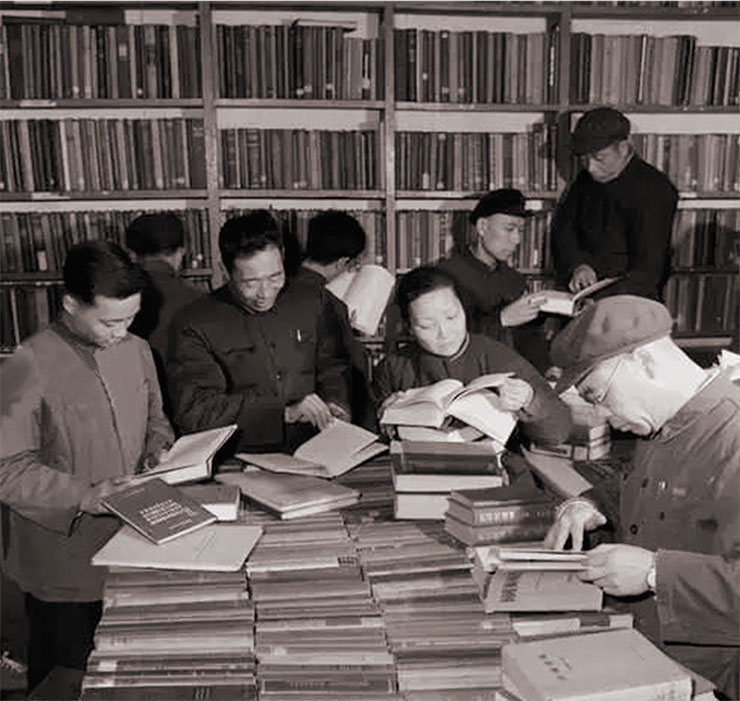

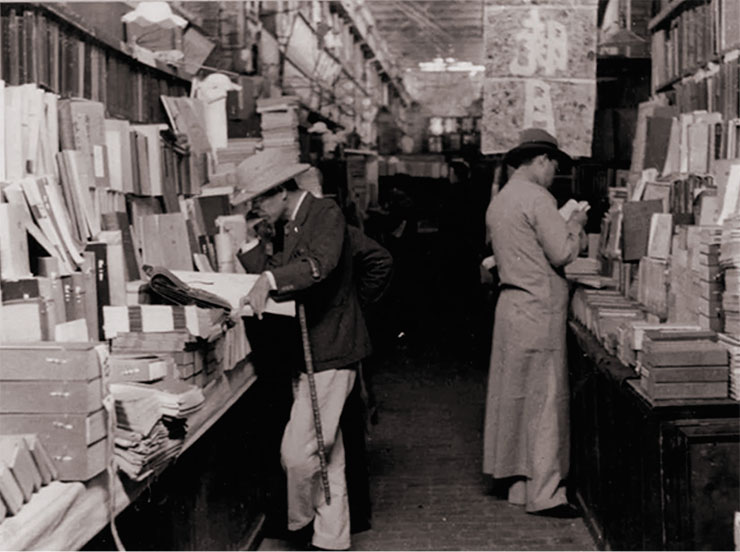

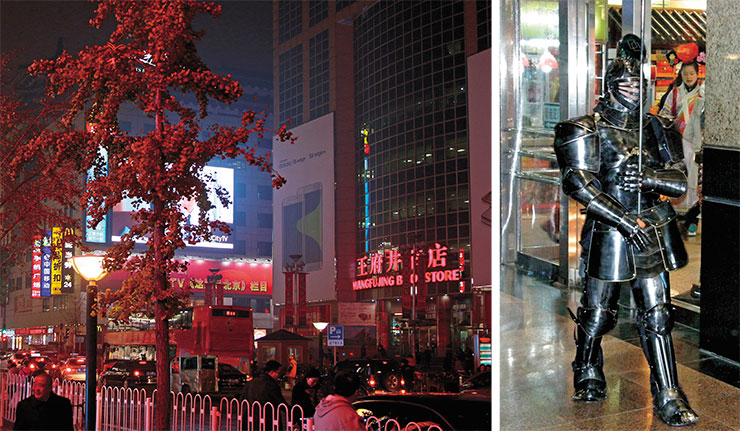

Continuing the conversation about commerce, we should highlight the bookselling trade in Wangfujing. The largest (five-story) Xinhua Shudian bookstore is located at the beginning of the street; about three hundred meters away, you find a bookstore specializing in foreign languages’ books, and further away, you reach the famous Sanlian Shudian bookstore, which offers books from many regional and university publishers. Despite the fierce competition on the part of digital publications, the printed word continues to be in demand. This is not surprising as the first printed books appeared namely in China – several centuries earlier than in Europe.

The tradition of selling printed materials on Wangfujing dates back to the early 20th century, when many book stalls and shops emerged in and around the Dong’an market. Today, despite the competition from digital publications, the printed word continues to be in great demand in China

The tradition of selling printed materials on Wangfujing dates back to the early 20th century, when many book stalls and shops emerged in and around the Dong’an market. Today, despite the competition from digital publications, the printed word continues to be in great demand in China

Buyers often turn into readers, right next to the bookshelves, where they sit down with a book right on the floor. In recent years, they often tend to take swift shots of the necessary pages with their smartphones. Of course, vigilant booksellers are on guard, and they do not allow young people to fully indulge into the joys of the learning process. Trade is trade: first you buy and then you read. Before the advent of smartphones, one used to be much more loyal to such makeshift reading rooms. However, even today much depends on the personal qualities of both the seller and the buyer (or in this case, the visitor).

Finally, how could one do without ads? To attract the attention of potential readers (mainly to foreign literature by West European authors, who have not been very well known to the Chinese), booksellers widely use live installations with costumed characters representing the heroes of the books sold at the store.

From the “presidential” Peking duck to Donghuamen food stalls

Of course, we cannot but mention the numerous eating establishments – for every taste and purse. As soon as you enter the street, you might want to turn into a narrow lane (hutong) Shuaifuyuan, where you can savor (that’s the right word!) the famous Peking duck in a restaurant of the Quanjuide chain (its name can be translated as ‘The Collection of All Virtues’). This restaurant is considered to be the best in its class, which is why US President Richard Nixon dined there during his historic visit to China in 1972. Everything is perfect here: both food and service and the interior decoration. The bill, however…

For many years in Donghuamen Street, which adjoins the central part of Wangfujing, there was a very popular row of evening food stalls, where one could try the whole variety of traditional Chinese cuisine, including the exotic fried scorpions

For many years in Donghuamen Street, which adjoins the central part of Wangfujing, there was a very popular row of evening food stalls, where one could try the whole variety of traditional Chinese cuisine, including the exotic fried scorpions

In our opinion, one can perfectly explore Chinese cuisine in an eatery on the opposite side of the street, where one can try Tianjin baozi (meat-filled steamed buns), an excellent breakfast for a modest fee. By the way, further down Wangfujing there are two more restaurants with Peking duck, where presidents did not dine, so the prices are several times lower.

Tea lovers might want to visit the famous tea establishment Wuyutai. Although it opened in Wangfujing as late as 1999, the respected trademark, or “old brand” (laozihao), traces its history to 1887. In Wuyutai, one sells tea, one generously offers tea, one tells stories about tea traditions.

Of course, you see American fast food chains here too: McDonalds, KFC, Starbucks. But what can we say about them? They are the same as everywhere, which is, in fact, their main strength.

But the most immediate acquaintance with the diverse Chinese cuisine – literally, sizzling hot – was offered, for many years, by the evening food stalls in Donghuamen Street, which adjoins the central part of Wangfujing. Alas, a few years ago, the authorities decided to “civilize” this place by transferring both cooking and eating – food was boiled and fried right in the street – into pavilions built specially for the purpose.

Of course, food there will be good, and hygiene will be better, and the prices, albeit higher, will not be fatally high. But still, we will forever miss this sense of culinary freedom, where every evening, by the light of lanterns, exotic foods were boiling and sizzling on an open fire, where Uyghur grill masters (who, by the way, never had change) were loudly calling people to their stalls, where you would hear the hysterical laughter of Japanese tourists who’d bought for a selfie a skewer with fried scorpions, and now they didn’t know what to do with them: “They aren’t for eating, you’re joking…”

However, there still remains a night market next to the “New China flagship store,” where you can get by turning under a brightly painted archway near the entrance to the alley and walking a little further under the red lights. This market still retains echoes of the old street trade, when one could exchange news with the sellers and have a discussion about the prices and merits of their goods.

And there still remains quiet joy that somewhere in the alleys you might come across a classic Lanzhou noodle shop where you can get for just a few yuan a large bowl of hot homemade noodles with some beef and greens. Just add to them a spicy pepper sauce – and, you know, life is not in vain.

Time defines what the street looks like

May our readers not be repelled by the fact that we talk so much about prices – this is not from a natural disposition to parsimony. And this is not about expensive things not always being good and vice versa. The reason is that most of the people coming to Wangfujing were, “after all, the ordinary men”. And the prices affordable to them were one of the most important features of the street, i. e., its democratism, which, unfortunately, is gradually disappearing.

As shown above, the history of Wangfujing reflects the most important political realities and economic reforms in the country. In 1915, Yuan Shikai, the first president of the Republic of China and a failed contender for the imperial throne, renamed this street after George Morrison, an Australian-born Englishman who served as a reporter for The Times in Beijing and had an apartment in Wangfujing. He became an adviser to Yuan Shikai, helped him develop a plan to restore the monarchy, and in 1919 represented the then Chinese government at the Paris Peace Conference.

After the People’s Revolution of 1949, the street accommodated new institutions, such as the editorial office of Renmin Ribao (The People’s Daily), the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. It was deemed inappropriate to have a street named after an “agent of British imperialism” in the capital of the new state, so it was decided to return the former name. During the troubled years of the “cultural revolution,” the street was also “revolutionized,” having become People’s Street for several years, but as early as in 1975, the authorities of the country and the city restored the name Wangfujing, a name kept in the memory of native Beijingers.

The construction of St. Joseph Church was completed in 1655. The architects of this Catholic cathedral were among the first Jesuit missionaries in China: Gabriel de Magalhães, a Portuguese, and Lodovico Buglio, an Italian astronomer and theologian. The cathedral’s current architectural appearance, in the style of the Romanesque revival, was adopted in 1904. Today you can see here wedding processions and, on summer nights, dancing people in the courtyard in front of the main entrance

The construction of St. Joseph Church was completed in 1655. The architects of this Catholic cathedral were among the first Jesuit missionaries in China: Gabriel de Magalhães, a Portuguese, and Lodovico Buglio, an Italian astronomer and theologian. The cathedral’s current architectural appearance, in the style of the Romanesque revival, was adopted in 1904. Today you can see here wedding processions and, on summer nights, dancing people in the courtyard in front of the main entrance

One of the perpetual witnesses of the times has been the three-nave cathedral, which stands in a large court behind fragments of an openwork stone fence. Named after St. Joseph, it is also known as the Wangfujing Catholic Church or the Eastern Church (Dongtang). It was erected in 1655 on the land granted to the Jesuit order by the Qing emperor.

The building suffered many times from earthquakes and fires; the last time it was almost completely burned down by the Yihetuan Movement, i. e., participants in the uprising against the Europeanization of China, who captured Beijing in 1900. But through the efforts of the parishioners and, presumably, with the help of the brothers and the funds of the Order of St. Ignatius, the cathedral was restored again.

The current cathedral was rebuilt in 1904. During the cultural revolution, it was used as a warehouse, but as early as in 1980, it regained its original purpose, and now it successfully fulfills its duty of guiding the flock (by the way, there are more than two million Catholics in China). In its vestibules, you can see elegant couples dressed according to European standards, who have arrived here to perform a marriage ceremony. And in the evenings, townspeople arrange dance parties on the adjacent land site.

Between the East and West

Since the end of the 20th century, Wangfujing, a large part of which was closed to traffic and made pedestrian, has been receiving, especially in the evenings, tens of thousands of tourists, attracted by the hundreds of shops run by famous Chinese and European brands; by tea houses; by restaurants and the “food street,” where you can try not only local snacks but also a variety of delicacies offered by the exotic South Chinese cuisine (snakes and frogs included); by souvenir shops with long rows of tables and baskets full of cute little Chinese things “all for 10,” “all for 15,” and so on, a simple way to purchase gifts for all the relatives, friends, and colleagues.

Finally, crowds of tourists are also attracted by the unique atmosphere created on a summer evening by dancing people, by musical performances, and by various installations and open-air shows arranged mostly right on the sidewalks in this street, full of signboards and shiny ads.

A noticeable point of attraction is the bronze sculptural compositions installed along the sidewalk near large shopping pavilions and in the lanes near the shops.

Near the sculptural compositions in the street, you can see not only tourists but also local people who stroke the heads of the bronze children, sit down on the musician’s lap or hug the woman with a tambourine. The points of contact “for good luck” shine with a pristine metallic sheen

Near the sculptural compositions in the street, you can see not only tourists but also local people who stroke the heads of the bronze children, sit down on the musician’s lap or hug the woman with a tambourine. The points of contact “for good luck” shine with a pristine metallic sheen

Here you can see kids playing at a huge shoe near a shoe store and a merchant offering, with a sly smile, a dish with real fresh buns. You see a barber who has shaved the forehead and part of the head top of an elderly Chinese and is diligently weaving the rest of his hair into a braid (mandatory hairstyle during the Manchu rule). You see a couple of musicians: an elegant woman in a long flowery dress with an octagonal tambourine in her hands; she is accompanying a pensive maestro, who is sitting on a low stool and playing the huqin stringed instrument. And, of course, you see the unrelenting symbol of old China – a running rickshaw and his cart with a passenger seat and a canopy folded behind its back.

Most often, you can see tourists near the sculptures, who sit down in the rickshaw cart or on the lap of musician, stroke the head top of the bronze barber’s client, or hug the woman with a tambourine.

In the evenings, you can meet here real street musicians playing the erhu, an ancient bowed two-string instrument, whose special oriental melodies touch the souls of Beijing people of all ages.

In addition to realistic sculptures, you can also see modern art in Wangfujing, e. g., the sculptural group “Five Bulls as Five Fortunes,” created by the famous artist Zhu Bingren. However, this creative piece is based on the famous painting “Five Oxen,” dated to the Tang epoch (618–907). By the way, the painting is kept not far from Wangfujing – in the collection of the former Imperial Palace, now the National Gugong Museum

In addition to realistic sculptures, you can also see modern art in Wangfujing, e. g., the sculptural group “Five Bulls as Five Fortunes,” created by the famous artist Zhu Bingren. However, this creative piece is based on the famous painting “Five Oxen,” dated to the Tang epoch (618–907). By the way, the painting is kept not far from Wangfujing – in the collection of the former Imperial Palace, now the National Gugong Museum

However, since the beginning of the 21st century, Wangfujing’s appearance has been gradually changing. Commercialization, multiplied by globalization, has reached here as well. New mirrored multi-star hotels and expensive boutiques are emerging, and the ads run by well-known Western brands are getting louder. It can be argued that the values of consumer society have penetrated the minds of the middle and young generations. So the famous street is rapidly transforming to meet the needs of consumer society, and in doing so it is losing its special, inherent flavor of mysterious East, which, from time immemorial, has fascinated people of other civilizations with the enigmatic charm of its ancient culture.

From the point of view of city dwellers and the Chinese population, which is getting increasingly wealthier, Wangfujing Street is rapidly transforming into a path to the Western world. On the one hand, its design demonstrates the economic growth and production capabilities of modern China, postulating its place in the world of modern standards and values; on the other hand, it dissolves the historical landscape and extinguishes the spirit of traditions, which determined until recently the special flavor of this iconic place.

However, it turns out that the national specificity of the ancient civilization does not wash away so easily. In Wangfujing, it survives in the remnants of the market, which are hiding in the depths of the adjoining hutongs; it continues to live in the special Chinese cuisine with its amazing variety of foods. The national spirit hides behind the traditional bright-colored three-gate arches in front of hotels and restaurants as well as in hieroglyphic inscriptions, which appear mysterious to a foreigner, and in the figures of the mythical “Chinese unicorns” qilin and bixie at their entrances. One can notice it in the petty street trade at night, in the shops full of exquisite china, and in the phenomenal variety of teas in large expensive shops and tiny ones; one can read it in the abundance of literature, both old and new, on the second-hand book markets; one can even hear in the rumble of swift and spry motorized rickshaws, which have replaced the physical traction of fleet-footed youngsters.

It is snugging in special shops that sell all sorts of chopsticks, from disposable to ceremonial ones made from mahogany and silver-and-enamel. It is hiding in small art shops with their phenomenal product range: many varieties of rice paper and brushes – from pig bristles to ermine – for calligraphy; black ink tiles with gold patterns, which need to be ground and diluted in water before use. It is winking from workshops with carmine paint sticks and stone blanks for personal stamps, which will be immediately cut for you in any shape and color.

And, of course, the tradition triumphs in the evening street calligraphy contests whose participants write hieroglyphs on the sidewalk with water and a brush as large as an actual broom. These hieroglyphs will live on the pavement until the moisture dries out…

With this symbolic image, we would like to end our short tour of Wangfujing. After all, the admiration for its beauty and artistry, as well as for calligraphy, never fully disappears because it lives inside us. Fortunately, the need for live communication and personal impressions has not yet given way to the virtual world. Therefore, everyone who has had a chance to walk along this noisy, colorful, sometimes annoying but very hospitable street will forever remember its unique appearance and recall it with a kind smile.

References

Beijing bamiancao, ni zai nali? (Bamiancao Street in Beijing, where are you? // Media portal of the Sohu Internet company. Sept. 29, 2019. URL: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1645988547043115501&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed Dec. 25, 2022).

Komissarov S.A., Solovyev A.I., and Kudinova M.A. China, diverse and eternal // SCIENCE First Hand. 2019. N. 2 (52). P. 68–113.

Li Chaorong, Yu Jincheng, Feng Xiangwu. The Wangfujing Paleolithic site in Beijing // Chinese Archaeology. 2001. V. 1. N. 1. P. 85–87.

Minguo beijing jiu ying: 1938 nian dong'an shichangde shangpu (Old pictures of Beijing of the Republic period: Dong’an market stalls in 1938) // Baijiahao (free text depository). Sept. 29, 2019. URL: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1645988547043115501&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed Dec. 25, 2022).

Wangfujing, jinjiede yibai nian! Zhexie lao zhaopian tai chengui (Wangfujing, the 100th anniversary of the golden street! These old photos (possess) exceptional value) // Huasheng zaixian (Voice of China Online: Hunan Ribao newspaper news site; posted on the All-China Information Portal Xin Lang Wang (New Wave Online). June 24, 2019. URL: https://k.sina.cn/article_2288064900_8861198402000mkns.html (accessed Dec. 25, 2022).

Zhou Yuekai. History of Wangfujing Street / Trans. from Chinese by T. Mironova // Confucius Institute. 2020. N. 3. P. 18–23 [in Russian].

Photo materials for this article were either created or prepared by A. I. Solovyev