Kanas at the Heart of the Chinese Altai

Several years ago, even in the pre-COVID era, our small yet cohesive team was vigorously traveling across Xinjiang to collect archaeological materials for science projects supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (now part of the Russian Science Foundation). We drove from Urumqi to Turpan, a route well-explored by tourists, which had not made it less fascinating though; visited the museum of Yining (Ghulja), a town lost in the steppe; and made a fairly risky trip to the south, along the Aksu–Kashgar line. But the topmost point (in all respects) of our travels was a visit to a city called Altay, a name cherished by every Siberian. This small, cozy city, closely reminiscent of Gorno-Altaisk, the capital of the Republic of Altai in Russia, became our base location in exploring the nearby natural and archaeological attractions

The Altai Mountains are a unique natural phenomenon located in the contiguous areas of Russia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and China.

Bare rocks and snow-capped peaks; ridge slopes covered with dense green coniferous forests and shrubs; narrow gorges and expansive valleys stretching into the blue horizons; fast rivers boiling with foam at smooth boulders and sharp rocks blocking the riverbed; the quiet surfaces of cold lakes lying in-between mountains and in the dark depths of ancient calderas; red flashes of wild rosemary and peony on mountain slopes; austere barrens, where dwarf trees make their way through a layer of kurumnik, a flow of pebbles and rock fragments rounded by glaciers… Above all this lushness, the sky unfurls a dome with tender clouds staying as if frozen at distant peaks and with the clear contours of feathered predators, floating in the air, their wings outstretched, rising up with the rising of warm air.

A light wind flies by, carrying along bird songs and cicada crackling and the savory smell of mountain herbs. The Altai Mountains are rich in surprises. They can grant you a meeting with a family of deer or a colony of marmots, or tickle your nerves with fresh tracks of a bear, lynx, or wolf. If you are particularly lucky, then in deserted areas you might have a chance to see through binoculars the spotted figure of a snow leopard, one of the rarest Red Book species.

The Altai valleys are rich in archaeological sites of different eras. In Russia, these are the caves of Denisova, Kaminnaya, and Razboinichya; the Paleolithic sites of Kara-Bom and Kаrama; the rock paintings of Kalbak-Tash and Elangash; and the famous “frozen” mounds of Pazyryk, where the local permafrost had helped conserve not only tattooed mummies but also unique finds made of organic materials: colorful carpets, felt appliqués, wooden tables, dishes, horse harness decorations, and even a four-wheeled canopy chariot.

In Mongolia, these are the culturally akin “frozen” mounds of Olon-Kurin-Gol, which preserved ancient articles made of felt, antler, and wood; ancient Turkic memorials; and tens of thousands of petroglyphs. In Kazakhstan, these are the Berel mounds of the same cultural communion, which presented, among other finds, yet another “Golden Man.”

Speaking about China’s Altai Mountains, here the main attractions undoubtedly include the Kanas Nature Reserve and a variety of archaeological sites, primarily the Chemurchek and ancient Turkic anthropomorphic statues, which have been museumified and have become popular tourist attractions. In this ancient region, nature and man have shaped a unique historical and cultural landscape in the mountainous country.

On the banks of the Irtysh’s tributary

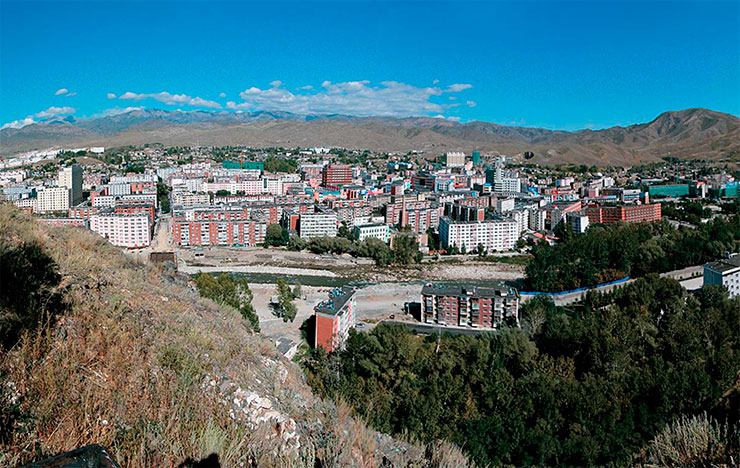

In the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, which borders on Russia and Kazakhstan in the north and on Mongolia in the east, at the foothills where semidesert landscapes abut mountain spurs, there lies a city, a relatively small one by Chinese standards. The city’s name is Altay (Aletai 阿勒泰), and it is the administrative center of a prefecture of the same name. Its streets stretch along a wide valley cutting into a mountain range. A narrow river flows through the valley – this is a tributary of the famous Irtysh River, which then flows through the vastness of Kazakhstan, where it gains strength, and reaches Siberia, where it debouches into the Ob River in a powerful stream.

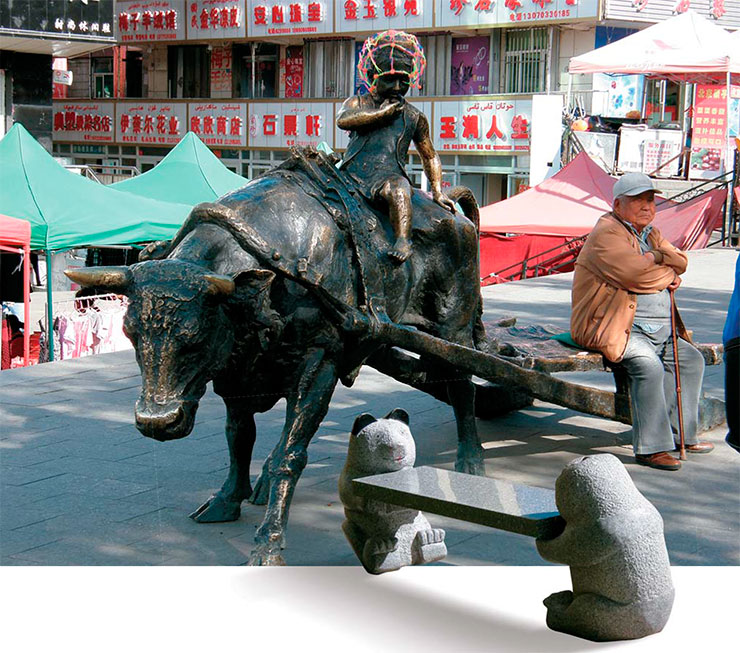

On the streets, you meet riders on horses or camels, parading loftily among the vehicles of modern civilization. You readily notice signs of a multinational community (although half of the local population are Kazakhs, there are also more than a dozen nationalities) not only in the clothes of passers-by but also in the numerous sculptures decorating the city’s avenues and parks.

You see bronze horsemen fighting desperately for a goat carcass in Kok boru, a traditional equestrian game. Another sculptural composition reproduces the scene of a reckless horse chase as part of the ancient Kyz kuu (“catch up with the girl”) ritual. Yet another one, a bronze bull with a yoke around its neck and a boy on its back, dressed in a sleeveless vest and a round cap typical of the local Turkic population, is dragging a bronze sledge right in the middle of the sidewalk. City people often sit down on it to rest and share news.

The city also has a small local history museum with a modest yet fascinating collection of stone statues dated to the ancient Turkic times. Some of the statues differ from their counterparts in the Russian Altai due to the noticeable influence of Sogdian traditions.

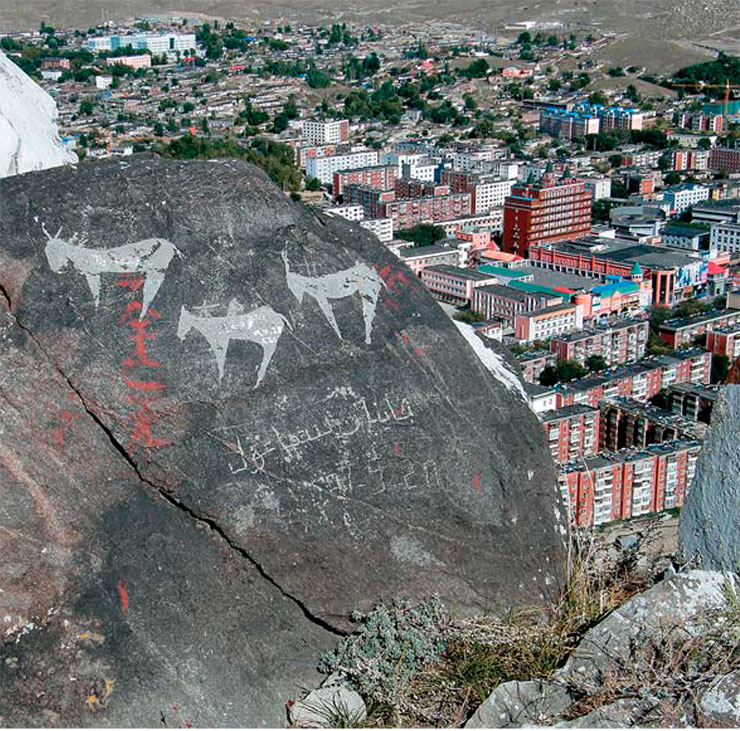

Remarkable finds are also stored at the museums of the administrative centers of the neighboring Burqin and Kaba (Habahe) Counties: a fragment of a rock plane with an ancient petroglyphic image of a skier; round stone staffs of the Seima –Turbino appearance, dated to the advanced Bronze Age, made of pebbly material and crowned with realistically crafted male faces; weapons of the Scythian and Mongol times.

However, Altay’s main showplace, which attracts visitors from all over China as well as from abroad, is the Kanas National Park (喀纳斯).

Kanas: three in one

The Kanas National Park is the core of Chinese ecotourism. It has the status of a forest park, geopark, and ethnopark simultaneously. Its area is an incredible 5588 km2 with a height difference of 1300 to 4374 m. It is planned to gradually expand the nature park to 10,030 km2, thereby turning it into the largest one worldwide.

Every year the nature park receives a huge number of visitors. According to official data, in 2019 (the last pre-covid year), more than 10 million people visited it in the first nine months alone! Not to mention that the harsh weather of the Altai highlands noticeably shortens the tourist period (here, it is from May to September).

Now, after two years of recession, tourism is restoring quiet rapidly in this area, and the number of person–visits over the first seven months of 2023 achieved a level of two million.

The park has strict zoning; i. e., its area is divided into the main, buffer, and experimental zones with different environmental management regimes. Most of the park is a highly protected area, where tourists are forbidden to enter. The main problem, which had been until recently a nightmare for ecologists and the park management, was the Altai gas pipeline (Sila Sibiri 2), which was supposed, according to the project, to go through the Kanas Pass on the Russian–Chinese border and inevitably cross the park’s area. However, according to recent decisions, the gas pipeline will pass through the steppes of Mongolia instead of the Xinjiang Altai.

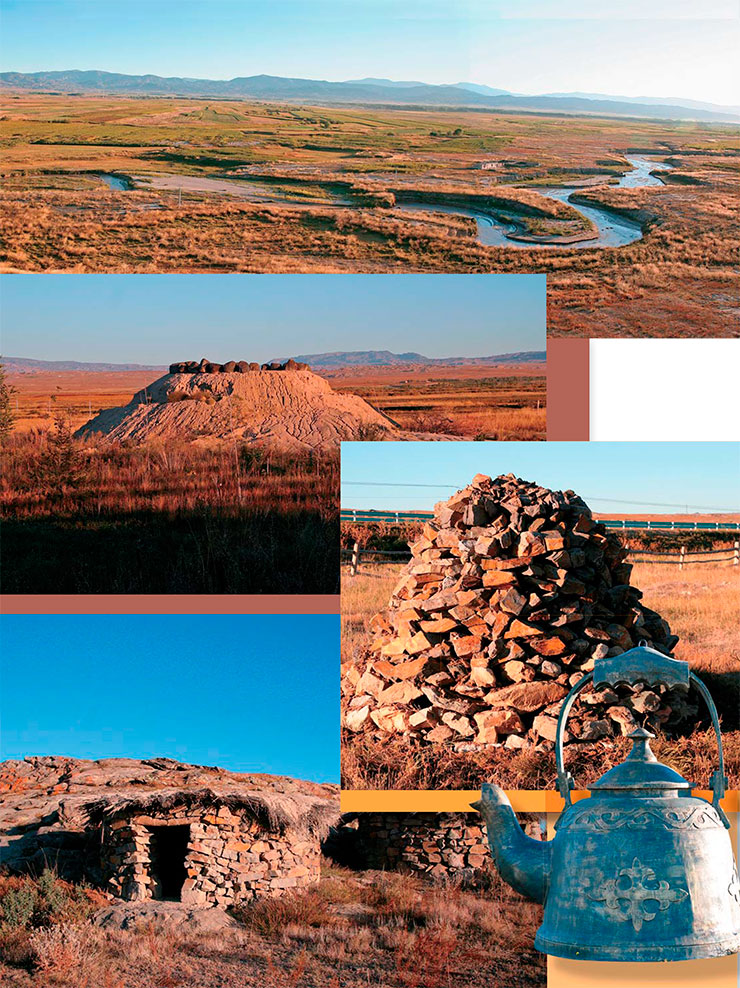

An excellent asphalt road leads to the very borders of the nature reserve, crossing mountain passes. Sometimes it runs through small gorges cut by builders in glacier-smoothed rocks. Perhaps, here once passed one of the northern branches of the Great Silk Road, which now reminds of itself with the ruins of the walls of abandoned caravanserais.

Shaggy camels, chewing withered semidesert plants or standing proudly on sandy hills or on screes of disintegrated outcrops and casting indifferent looks at scurrying vehicles, show up as visions of another, distant life, when groups of people and lines of packed animals were walking slowly along the mountain ridges.

Open-air museum

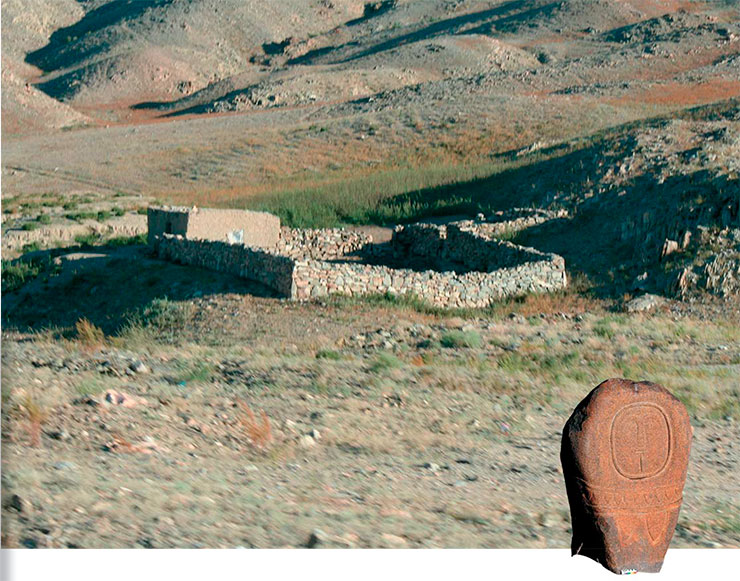

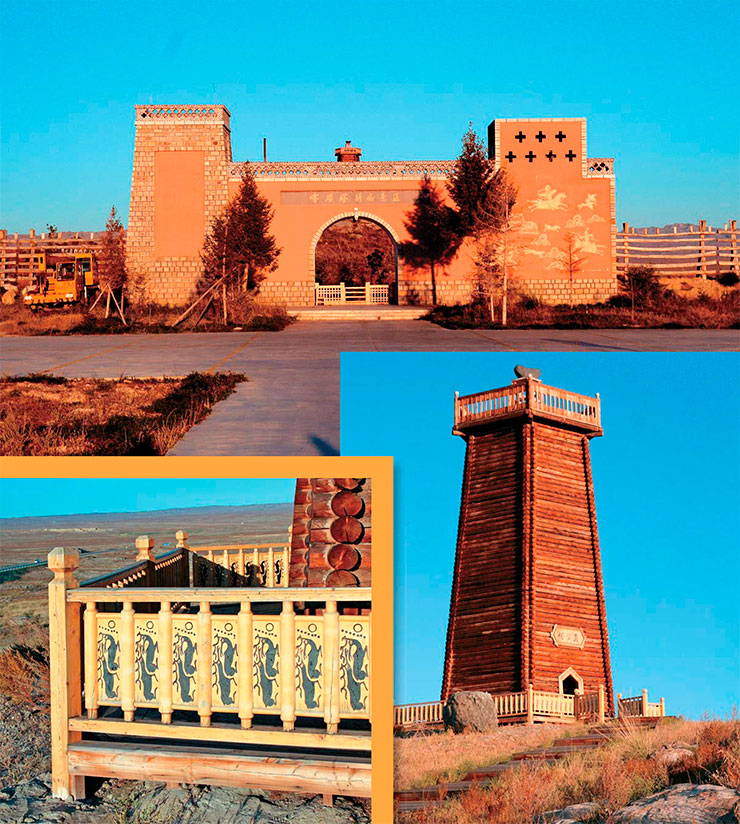

Along the road to Kanas, you can still see old paths leading to the foot of the mountains and to the low, silted banks of seasonally dry rivers. One of these paths leads to the base of a smoothed rock platform, where a historical open-air museum was created. Its gates are stylized as a passage in a fortress wall between two towers, one of which is decorated with panels showing horse hunting scenes, depicted in a medieval graphic style.

Inside the fenced area, a tall hexagonal log tower stands on a glacier-licked moraine. The fence around the tower shows images copied from deer stones, i. e., slabs with ancient depictions of deer as a main figure.

The museum area also displays a large group of copies of anthropomorphic stone statues attributed to the Chemurchek culture, which were created on the surface of vertical pebble boulders; replicas of on-land dwellings with walls made of wild stone; full-scale models of domed and pyramidal grave stone structures; various wooden buildings. Here you can also see reconstructions of sacred Bronze-Age sites. Thus, the relatively small museum area represents all the main archaeological periods in the development of the region.

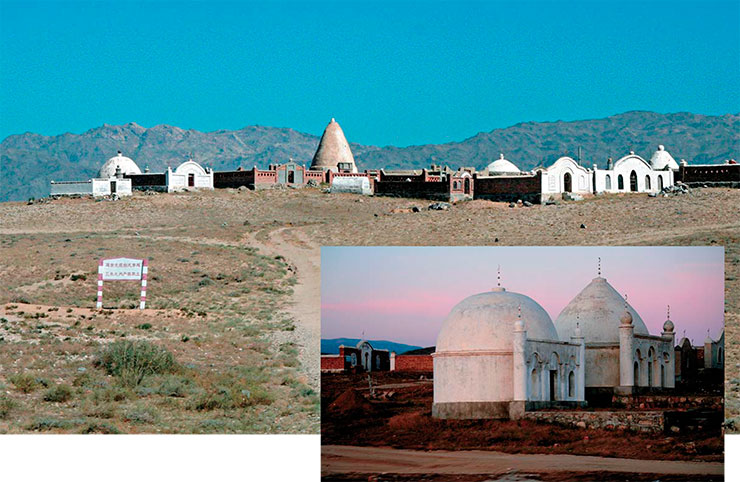

When the route passes through a plain, you may come across a variety of mazars, i. e., funerary structures of the Islamic (Kazakh and Uyghur) population. They form entire “villages of the dead” with their own streets and alleys. The buildings vary in size from miniature to very impressive ones, which may be as large as a full-fledged mausoleum. These structures, together with a common brick wall, largely resemble the forgotten medieval cities in the depths of Central Asia.

On the opposite side of the road, you might notice small earth embankments, sometimes with a stone ring at the base, which are very reminiscent of medieval mounds. Near them stand small steles made of concrete or stone. These are burial structures of the Han people, i. e., the Chinese population of the region.

On the way to the nature reserve in wide valleys near the streams, you can see an abundance of snow-white summer yurts and lazy herds of yaks and horses of different colors. The Tuvan people, who own these dwellings as well as two ethnic villages, arrive here for their seasonal national holidays.

In the vicinity of one of the villages, you can visit a stone sculpture museum, a site of undeniable scientific and educational interest. The ancient statues are mostly displayed along a path that crosses the hill and leads to other buildings and exhibition areas, such as the Shendao “alley of spirits” in a funeral ensemble of elite tombs. When you follow it, you see creations of Chemurchek and ancient Turkic artists and stones with hoof prints carved on their surface by nomads of the Scythian times.

The gallery also contains examples of how medieval artists were “improving,” according to their tastes and views, the works of their predecessors. It is especially interesting to see traces of painting on the surface of one of the stone statues. This is a serious argument for claiming that the statues were painted at the time of their creation.

The displayed museum’s collection is complemented by bronze sculptures that reproduce traditional elements of the ceremonies and material culture of indigenous population in this region.

Enchanting Lake

No matter how fascinating the sights are along the route, they only serve as preparation before seeing the main showplace of the national park – Lake Kanas. Its name is translated in different ways, with reference to the Mongolian and Tuvan languages or to one of the Turkic languages, as a “lake in the valley”, or a “deep lake”, or a “rich or mysterious lake” – everything works. We prefer the translation offered by China Radio International: “Enchanting Lake.”

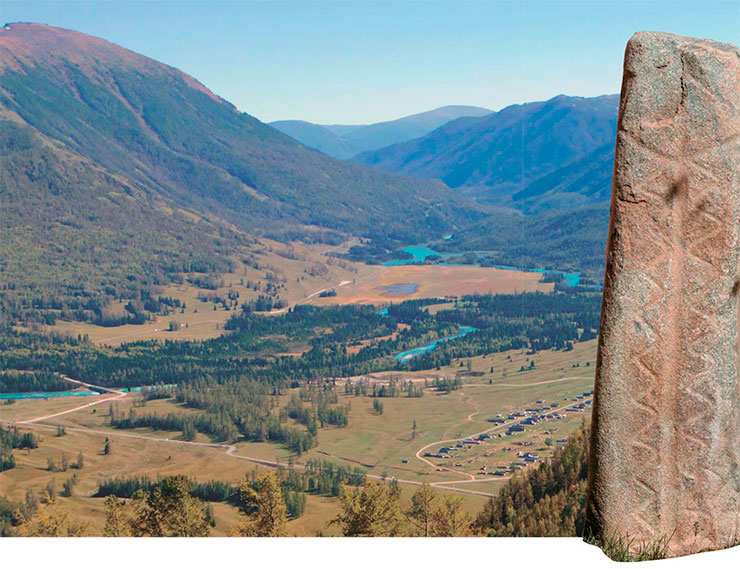

Those who wish to see the lake and experience the magic of this special place will have to climb 1068 wooden steps leading to the s. c. Fish Watching Platform. From there you can see the marvelous azure expanse, which fills the entire intermountain corridor extending from the main valley. Disappearing around the bend, the lake surface stretches towards a distant wall of jagged mountains on the horizon, which are topped by white snowy caps of the Friendship Peak (Khüiten, Nairamdal; 4,374 m) of the Tavan-Bogdo-Ula mountain range, whose glaciers feed this huge body of water.

The quiet surface of the lake reflects the sky, clouds, and green taiga, creating a unique visual effect. At different times, its waters can be blue–gray, light green, or emerald, which is why this water body is also known as the “one that changes its color.”

An amazing atmospheric phenomenon – Buddha’s Light in the Sea of Clouds – occurs sometimes on its shores. This phenomenon is associated with the passage of sunlight through clouds or fog over the lake and its reflection in the water. When the morning sun is at a certain angle to the lake surface, then a luminous circle with a rainbow halo may appear above the water in front of the observer in the direction of view. The circle contains a human silhouette repeating the movements of the observer. The color of the halo changes with the changing hue of the clouds and fog. Buddha’s Light continues for about a quarter of an hour and gradually disappears; seeing it is considered a very good omen.

From the height of the viewing platforms, you may sometimes see shadows sliding in the depths beneath the water, which, given a little imagination, can easily be associated with the popular local legend about an underwater monster Hu Guai, capable of dragging under water a horse or cow when they come here to drink.

The tourist will hear the story about the lake monster from the guide during the bus drive to the lake. No wonder that the number of so-called “eyewitnesses” is growing every year. Sometimes they see entire packs of monsters rising to the surface and then descending into the depths. Some ichthyologists who studied the local fauna suggest these are giant taimen fish. But how big should a taimen fish be to pull a horse? “No, wait,” thinks the intrigued tourist, “something’s wrong here. It must be some ancient plesiosaur. Why should our Kanas be worse than their Loch Ness?” Conjectures of this sort swarm all over the Chinese Internet.

Only a small part of the lake is now open to visitors. Unrecorded tourism is utterly impossible; all the routes are controlled by the reserve’s staff. However, it is allowed to make trips across the lake on motor boats and small vessels, for which there is a special pier. One can go by boat to three of the six bays of the lake; the other ones are located in the protected area.

There are remarkable objects in the tourist area: moraine boulders, which represent traces of ancient glacial activity. Paths were made to these objects, and stands were mounted with information about geology of the mountain ecosystem.

The south of Altai differs markedly from its north. The climate is milder here; the valleys are wider; and the mountains do not look so austere. Of course, places like these also exist in the north of the Altai Mountains. There, too, are marvelous lakes, mighty rivers, and beautiful landscapes; nonetheless, the nature in the north is not so benevolent to man.

An example is the famous Ukok plateau, where nature presents a harsh contrast to the landscapes of the Kanas ecopark although it has its charms and stays in one’s memory over a long time, striking one’s imagination by its outstanding wildness and austerity. The milky white calcareous waters of the Ak-Alakha River, the plateau’s main waterway, rush down from the snowfields high up in the mountains. Cold air descends from the white peaks and fills the river’s floodplain. The weather is very changeable. A vicious wind can strike anytime, and so can rain and snow, which might unexpectedly fall in the middle of summer.

Behind the white caps lies the Ukok plateau of the Russian Altai. In the 1990s, an expedition of Novosibirsk archaeologists led by Natalia Polosmak discovered here a “frozen” tomb of the Pazyryk culture with a burial of a young girl who later became known as the “Altai Princess.” In the southern part of the plateau, there is a natural park of the same name, but getting here is not easy as the journey may take several days and present many adventures.

There is absolutely no tree vegetation on the intermountain plains of Ukok, which look like (and, in fact, are) high-mountain tundra. In clear weather, the high sky is reflected in the bowls of small but deep lakes. However, such days are rare. Here you can meet cranes wandering in the shallow water in search of food, see red geese cutting through the surface of cold lakes, or notice a golden eagle floating over the white wall of Tavan-Bogdo-Ula, which almost touches upon the very close horizon.

The earth’s coldness is seeping through the thin turf and the soles of your boots. Coldness is everywhere: at the bottom of small puddles, whose edges are touched by ice in the morning; in the thick layered ice floes above the beds of watercourses and in the small streams oozing from underneath the ice; even in the low, withered grass and the curvature of rare dwarf birches... And yet there is a pass in the wall of the Tavan-Bogdo-Ula mountains, a narrow passage that leads into the Kanas valley, full of life and warmth

Nevertheless, places like the Ukok plateau present a huge concentration of archaeological sites, mainly funerary ones, which are clearly visible on their surface. In principle, one can hardly drive through the valleys of the Russian Altai without encountering chains of stone mounds from different periods. Especially many of them are found in the highlands, where cold winds blow even in summer and the snow-capped peaks are near. However, there are almost no burial mounds of past eras in the neighborhood of Lake Kanas (except for mazars and some other burial grounds of ethnographic times).

Such a contrast between the two regions, separated by the dark barrier of the jagged Bogdo-Ula mountains with their white fangs of snowy peaks and a single mountain pass, allows us to propose a most natural explanation: people lived on one side and buried their dead on the other.

The cold, meager space beyond the boundary created by the severe, insurmountable mountains with only one narrow, seasonal passage could well have been in agreement with their ideas about the “other world,” where the deceased went. One of the most important aspects of the funerary cycle is to make it easier for them to move to the “afterlife space” by alleviating the hardships of their posthumous journey and thereby at least partially guaranteeing their consolation. Therefore, ancient people chose those areas within the explored landscapes where they believed the “other world” to be closest. There they set up special sacred sites for contacting with the ancestors and built necropolises.

There is hardly any doubt that the ancient people who lived in the thriving lands of the Southern Altai, abundant with forests, waters, and pastures, must have known about the narrow mountain pass leading to the harsh and cold mountainous plateau. They might well have associated this location both with the “valley of the shadow of death” (Ps 23:4) and the starting point of the shortest path to the other dimensions. So they could have brought their dead here as there were no state borders back then.

On the southern foothills, the ancient nomads, just like their modern descendants, were pasturing their abundant herds, hunting animals in the now-protected forests, and singing songs about the wonderful Enchanting Lake. And – just in case – they were composing legends for strangers about a terrible monster guarding its underwater estate.

References

Baltabaeva K. N. Intangible cultural heritage of the Kazakhs of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China // Kazakhi Evrazii: istoriya i kul’tura (Kazakhs of Eurasia: History and Culture). Omsk: Omsk Gos. Univ.; Pavlodar: Pavlod. Gos. Ped. Inst., 2016. P. 58–68 [in Russian].

Istoriya Altaya (History of Altai), in 3 vol. V. 1: Drevneishaya epokha, drevnost’ i srednevekov’e (Ancient Era, Antiquity, and the Middle Ages) / Ed. by A.A. Tishkin. Barnaul: Altai Gos. Univ.; Belgorod: Konstanta, 2019 [in Russian].

Komissarov S. A., Solovyev A. I., and Kudinova M. A. China, diverse and eternal // SCIENCE First Hand. 2019. N 2 (52). P. 68–113.

Kovalev A. A. Chemurchek monuments of Xinjiang: artifacts, complexes, and burial structures // Drevneishie evropeitsy v serdtse Azii: chemurchekskii kul’turnyi fenomen (The Most Ancient Europeans at the Heart of Asia: the Chemurchek Cultural Phenomenon), St. Petersburg: MISR, 2015. Part II: Rezul’taty issledovaniya v tsentral’noi chasti Mongol’skogo Altaya i v istokakh Kobdo, pamyatniki Sin’tszyana i okrainnykh zemel’ (Results of Research in the Central Part of the Mongolian Altai and at the Sources of Kobdo, Monuments of Xinjiang and Peripheral Lands), pp. 240–279 [in Russian].