Japan: on faraway islands and the land of Yamato

Modern Japan is skyscrapers of iron, glass and concrete stretching to the heavens from the densely built-up areas of flat-roofed houses with square corners and rows of solar cells; tiled roofs of numerous temples and small green parks, playgrounds and municipal cemeteries hiding among the houses. Going by high-speed and not very high-speed railway, it is hard to see where one locality ends and another begins - so smoothly they flow into each other, divided only by small square fields, mountain ranges and tunnels bored through the mountains… You'd think what kind of archaeology and ancient history can you expect in a place like this? But here they are, right under your feet. Each of the Japanese Islands abounds in history, both specific for the locality and common for the country, which few nations in the world can boast

Any part of the cultural oecumene, each piece of its territory has its own, profound and original history. However, even just seeing it often requires great efforts as it is buried under the veil of the past and especially under the canopy of the present. Only in Japan antiquity rooted in the past millennia is built into everyday life and foreseeable future.

Life-giving tree

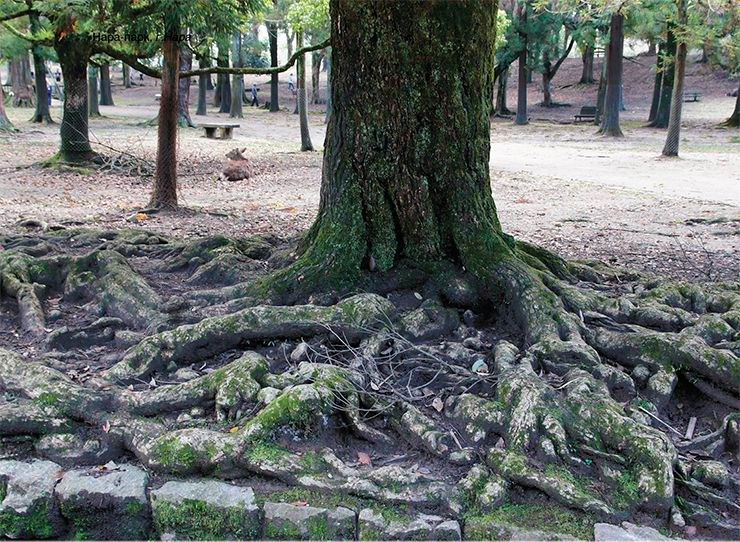

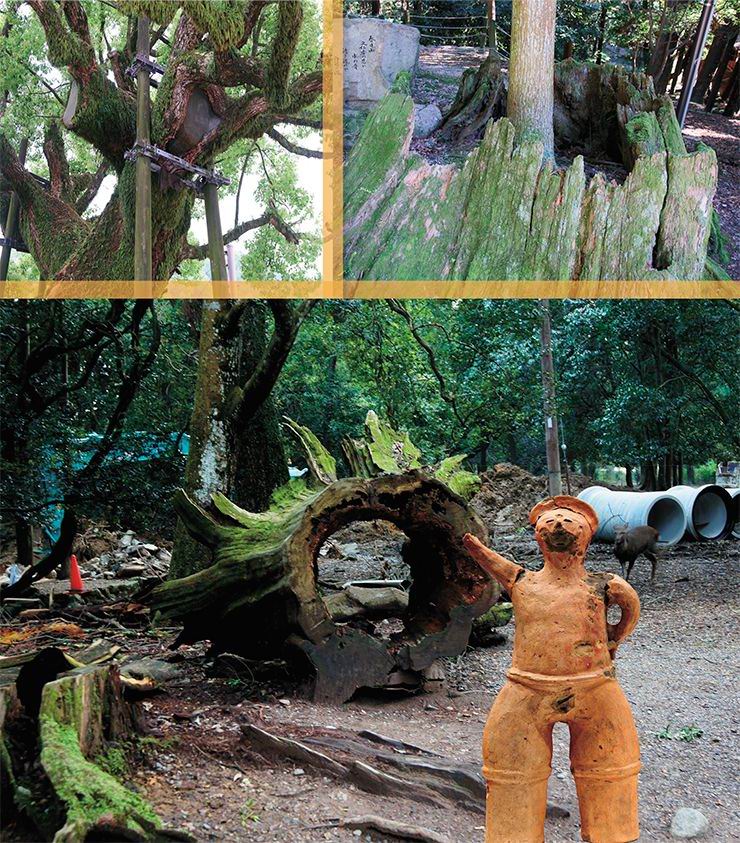

History is everywhere, even in the roots and trunks of gigantic trees, contemporaries of the First and Second Turkic Khagnates. These arboreal wonders, well beyond a thousand years, are well preserved behind the walls of just as old monasteries or in the depths of parks. Some of them are nothing but trunks and gigantic stumps covered with young shoots. In Russia or in any European country they would have disappeared long ago thanks to some sort of vegetation recovery program. In Japan, they are a constant and major concern.

Hundred-year-old lichen and the so-called "tan" of stones also shelter history. Like the trees, they are homes to kami, the spirits worshipped for centuries by the inhabitants of the Japanese Islands.

Time-darkened walls of the wooden temples timber for which was hewn by the craftsmen of the early Middle Ages (7th — 8th centuries) also bespeak history. The tools used were virtually identical to modern; the only difference is the composition and quality of the metal from which the blades were made. The building techniques used in today's wooden architecture are just as old, honed by centuries.

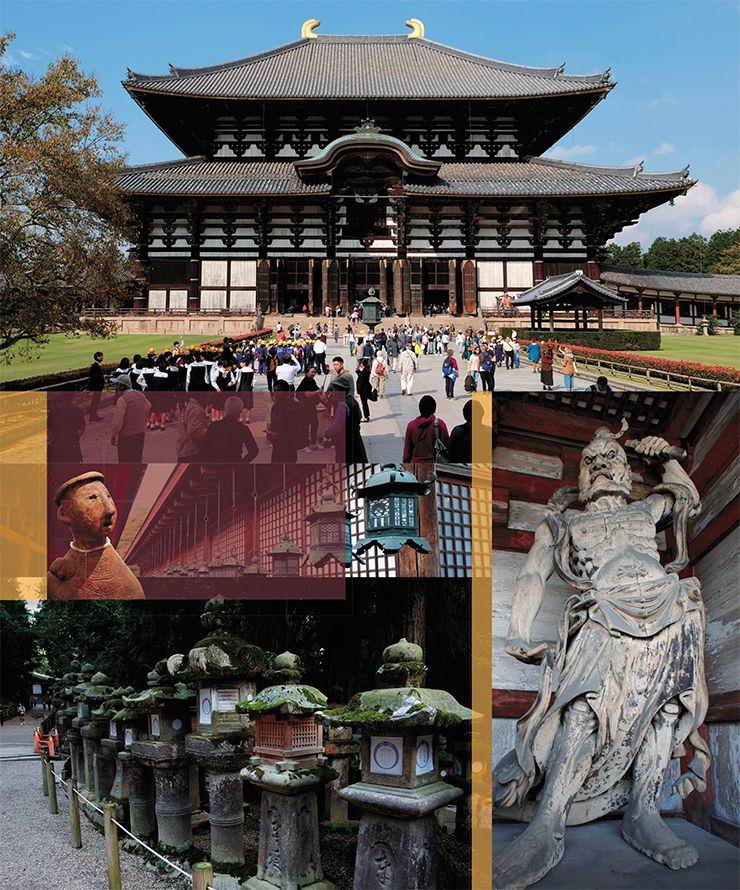

The city of Nara, ancient capital of the empire, which gave name to an early medieval period of national history (710—794) associated with the strengthening of Buddhism, is home to Tōdai-ji, or Eastern Great Temple, overwhelming with its grandeur and size. Erected in the middle of the 8th century, it remains the world's largest wooden structure.

The temple is approached through a couple of high and powerful entry gates including Namdaemun (South Great Door) with a double-pitched roof and five spans supported by columns made of monolithic tree trunks and guarded by the huge wooden sculptures of the monstrous Nyo guards. From the stairs of the gates, the temple does not look that big until your eye goes to the tiny figures of the people climbing its staircase, alone or in groups.

The enormous inner hall of the temple houses a bronze statue of sitting giant Buddha. They say that the statue was cast following seven failed attempts. If it is true or not, this special number confirms that the process sacred.

The true size of the sculpture — the biggest in Japan and one of the biggest in the world — is not appreciated at once. We grasped it during a spiritual ceremony.

On that cold winter evening, all the ancient bronze lanterns along the temple alley were lit. Pilgrims and a legion of tourists warmed themselves by the fire made in huge bronze receptacles at the gates.

Dark figures were streaming towards the temple's open gate lit from the inside by shimmering light. Through the blue-grey smoke the pedestal of the central statue showed.

At some moment, when the "chorus" sounded stronger, the barely visible folds of the enormous window-hatch under the roof ledge blew open — light beams burst in and plumes of fragrant smoke wafted through it. When they evanesced, in the upper window of the temple's immense dark interior, golden light flashed from the partly visible face of Buddha Vairocana. At this point, the majestic size of the sculpture came to light — its casting took almost all of the country's bronze and about a hundred and fifty kilograms of gold, not to mention thousands of tons of charcoal.

In the temple's interior, behind Buddha's back, there is a wooden column with a small oval hole at the foot, which goes into the foundation stone. The column supports the timber of the roof, which in traditional beliefs symbolizes the Sky, or Upper World. The sight of this colossal column and string of people queueing for it makes you think of the Tree of Life tying all the levels of the universe together.

Connected with this component of the temple's architecture is one of the most curious ancient practices. Its origin can be traced back to the beliefs of the traditional communities of Eurasia, with some slight variations. According to this belief, to ensure the success of an important new project, you have to squeeze through the hole in the column, headfirst. This equals the act of purification and leaving behind the accumulated burden of sin.

In a wide variety of archaic human communities, the tree symbolizes eternal life and renewal and is closely connected with human life. The indigenous peoples of Siberia worship the tree as the progenitor. For instance, in the forest areas of North Asia dead babies were buried the hollow of trees or in holes carved especially for this purpose in tree trunks, which were then carefully sealed to restore their original appearance. The babies were thereby returned to the womb they had come from. There were also the so-called "air burials" of adults in tree branches, having the same meaning. After all, the well-known log coffin is the image of a tree trunk. They used to take the sick to the tree roots in the belief that their powerful magic would renovate them and bring back to life. The aborigines of Siberia and inhabitants of medieval Europe would lean a woman having a hard delivery to a tree trunk — the source of the life-giving and renovating primeval strength of plants, which fade and resurrect every year (Eliade, 1998).

According to the beliefs of many peoples, to purify yourself, you had to crawl through a forked crown of a tree or, which is equivalent, between the legs of an adult woman. In some ethnic groups, an outsider who wished to be accepted by the community had to put his head between the knees of an elderly woman, who symbolized the foremother. All these sacred actions were a magic representation of the act of birth, the emergence in the world of a new being pure as a baby. The location and shape of the wooden column of Tōdai-ji and the hole at its footing indicate to this very meaning.

Heavyweight duel

When one speaks of Japan, everyone recognizes a combination of advanced technologies and old traditions of everyday life. Traditional women's clothes, unique Japanese cuisine, martial arts originating from severe samurai training, black with age Buddhist and Shinto temples and their modern-day equivalents painted red (their color scheme was influenced by Chinese culture), small joss houses and street processions resembling both carnivals and theatrical performances — all these phenomena have a long history, not always obvious and sometimes deeply buried. For instance, let us take traditional Sumo wrestling. To us it looks like a confrontation of two strapping fat guys who attempt to force each other out of a small circular earthenware ring delimited by rice-straw bales. Surprisingly, the chubby wrestlers move easily and rapidly; their physical strength is colossal. They force of their pushes and strikes must have flattened an ordinary man. In a moment, the opponent pops out of the circle or even rolls to the feet of cheering spectators.

Fascinating and exciting…but what special meaning might this heavyweight duel have? Wait till we look at this whirlwind match from the point of ethnography and you will see that we are dealing with an essential component of a most ancient civilization.

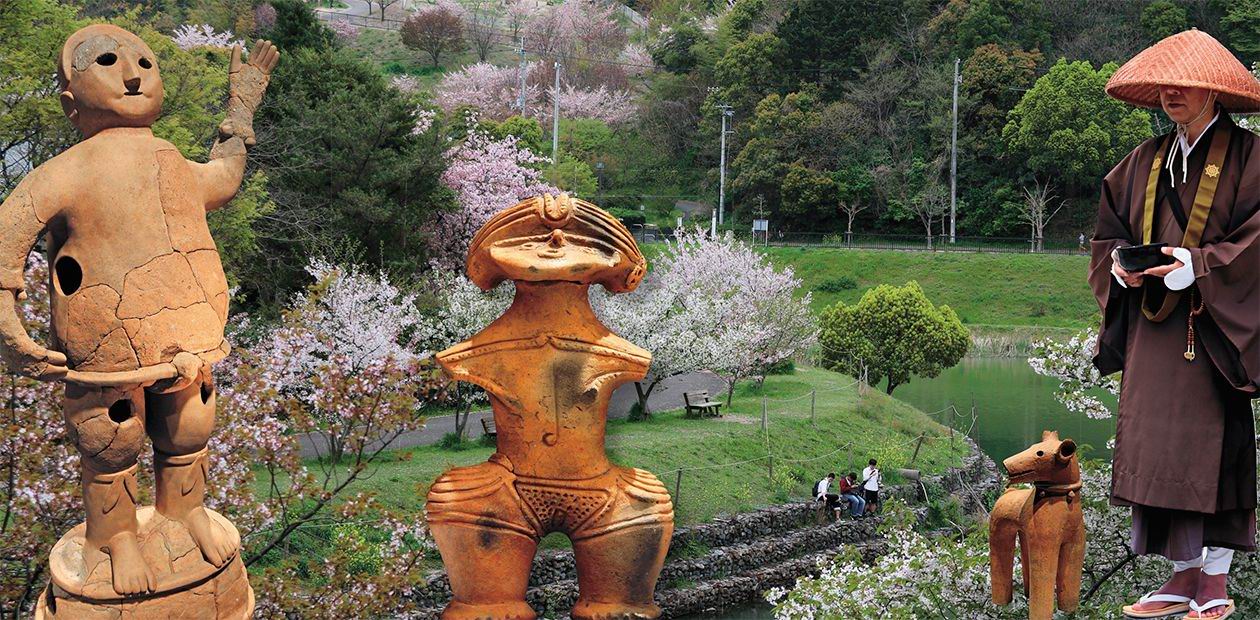

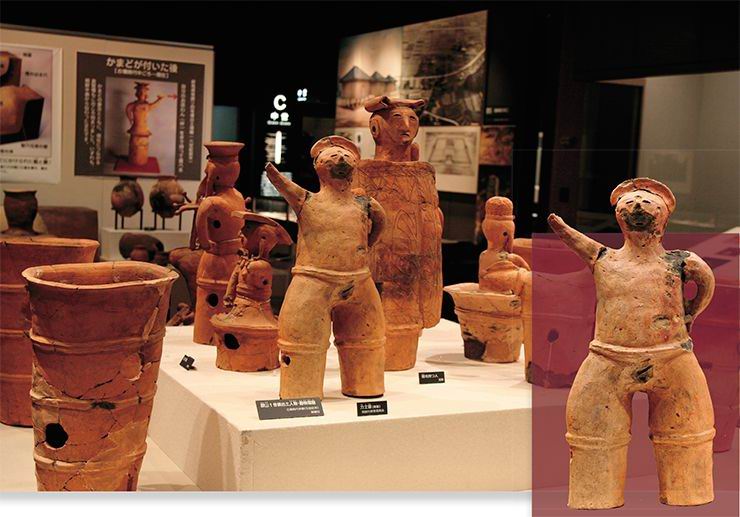

The first reliable written account of Sumo dates back to 642. However, judging by the Haniwa figures found in all large mounds of the Kofun period (3rd to 7th centuries AD), regular matches between powerful heavyweights started much earlier. In order to see the practical benefit of this show — hardly applicable to the extreme situations of nowadays — we should travel even further back in time, to a remarkable epoch in the history of the Japanese Islands referred to as the Jōmon period (13,000—9,250 BC, approximately corresponding to the Neolithic), when they started making pottery, applied new stone working techniques and began to develop agriculture.

That was the height of the maritime, appropriating economy, and the primary task of the Neolithic population (as well as of the humans living in much later periods) was sustaining life, above all, searching food. The density of the population was low and the communities were small. The cost of life of every able-bodied member of a community was incredibly high; any human loss threatened the well-being and probably even the existence of a community.

At the time, the areas that could provide easy life were relatively few. Besides, they had long been densely populated. All these areas were the subject of the aspirations and encroachments of the communities who happened to be "left behind," which inevitably resulted in conflict, including armed clashes. The consequence was losses at both sides, sometimes fatal for everyone involved.

This situation was typical not only for the inhabitants of the ancient Japanese Islands but virtually for all archaic human populations with various kinds of appropriating economy. In some regions — for instance, in the North Asian hunting and fishing communities of the vast forest and partially tundra forest belt — this lay of land preserved till the late Middle Ages.

In these archaic communities, including the ones thousands of kilometers apart, rules and regulations were being established with a view to restricting or avoiding massacres. According to a well-known word of wisdom ascribed to the Chinese military strategist Sun Tsu, the greatest victory is that which requires no battle. If the sides failed to achieve peace and a violent confrontation was inevitable, they agreed to combat to first blood, preconditioning maximum casualties, compensation for losses, etc.

The most common way to resolve a conflict became a fight between the leaders or specially chosen fighters conducted under certain rules, somewhat resembling a duel. For example, having thrown a spear, the warrior had to stand proudly and, cheered by his kinsmen, wait for the retaliation. Ethnographers describe another scenario, when the enemies were seated cross-legged against each other and took turns to stab each other. The one-on-one lasted till one of the opponents gave up or lost consciousness.

Needless to say, these "duels" required a significant degree of courage and cultivation. Equally often, disputes were resolved without weapons but within time constraints and need for certain skills. For example, the fighters had to wrestle on a slippery raw walrus pelt or up to chest in the water.

The society made special efforts to prepare such fighters. Thus, in the aboriginal communities of North Siberia, a “panel” of elders selected, basing on specific traits, boys fit for future combat. As the boys were growing up, they were to see these “medical boards” several more times. The health check included a visual acuity test, conducted by the stars. The chosen ones were excluded from working life and only had to undergo specific training. Of special importance were the exercises supposed to overcome water resistance — they are still common practice in sumo.

Over the past centuries, the practical side of sumo wrestlers had been growing less and less important until it disappeared completely. The mystic side, however, has preserved. According to the present beliefs, the earthenware sumo ring stands for the universe. The square arena symbolizes the Earth, and the circle surrounded by the shimenawa rope is a symbol of the sky. Man represents the Middle World. According to the expert of Japanese culture A. A. Nakorchevsky (Nakorchevsky, 2000), sumo contests conducted during matsuri (festival honoring kami spirits) are used for fortune telling. The wrestlers themselves are believed to have sacral power able to ward off wicked creatures.

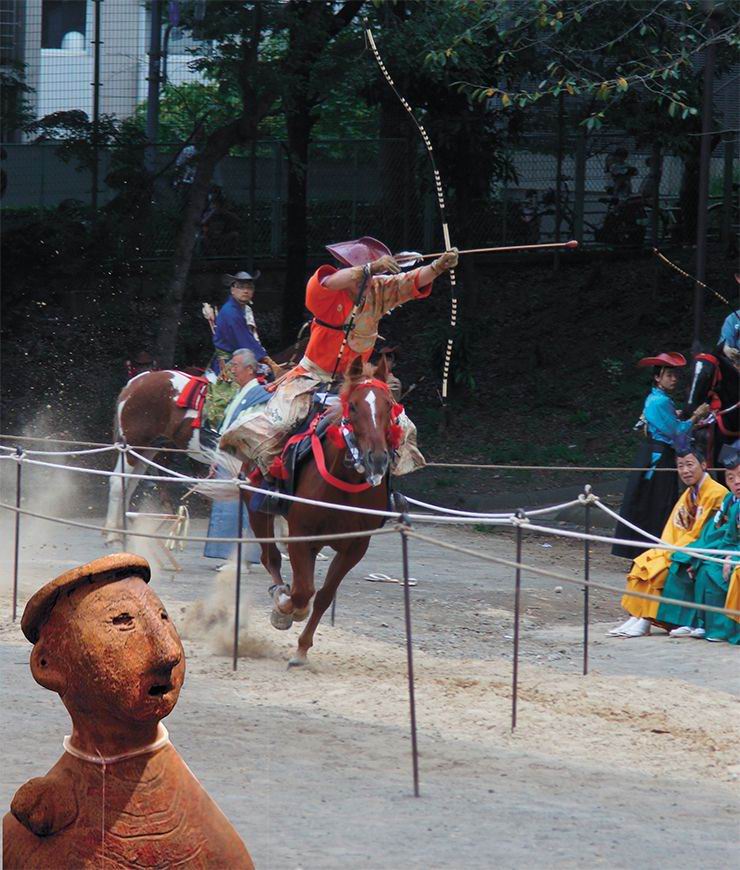

Another bright celebration with fairly transparent historical background is Yabusame, a mounted archery contest, where an archer on a running horse successively shoots arrows at a number of targets. The evident practical meaning of this event is impregnated with sacrality: the arrows target the evil. An arrow has long been considered effective in fighting evil spirits — its hard pike was able to defeat even the most wicked of them. Moreover, according to the beliefs of the ancient population of North Asia, the arrows were thought of as “alive,” capable of making their own decisions and reaching the target they have chosen (Plotnikov, 2001). Remember the Russian fairy-tale about the Frog Princess, where the arrows shot by the princes found a suitable life partner for each of them.

Walking along the lanes of historical parks

Everything said about history applies fully to archaeology — it is right under your feet. Archaeological materials enjoy a high profile in Japan’s numerous capital and provincial museums and in the modern culture of the population of the Japanese Islands.

Japan has many cultural and historical sites which are well preserved for the future generations: Neolithic sites, Paleometal settlements, medieval palace complexes … All of them are carefully studied, conserved and, maybe unexpectedly for us, restored in the form as close as possible to the original. Despite the very dense urban development and land issues, the government seeks to allocate and conserve large areas of ancient sites, sometimes measuring many hectares.

As these sites are studied, dwellings and fortifications are set up using ancient technologies and basing on the materials from digs. In this way, highly interesting and illustrative historical parks are built. Parklands are made around large mounds that have been built into urban architecture.

We should also mention a special phenomenon found in Japan. True research centers are established next to interesting, complex and large archaeological sites. For instance, the world-famous Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties is located along the border of the ancient capital, presently marked by narrow motorway instead of the former walls. As recently as in the 1990s, it was a low building with a small garage and modest premises for renovation works. Today, it is a four-storied building of steel, glass and concrete that has become home to the formerly scattered laboratories. On the patches that have already been excavated, the entrance gate to the medieval Japanese capital has been restored.

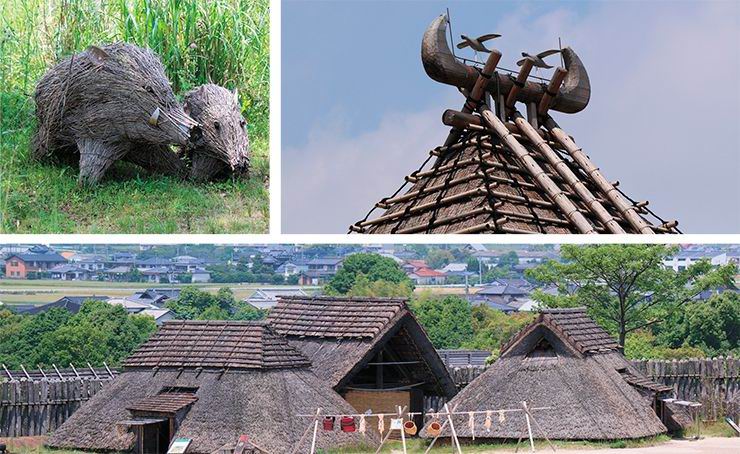

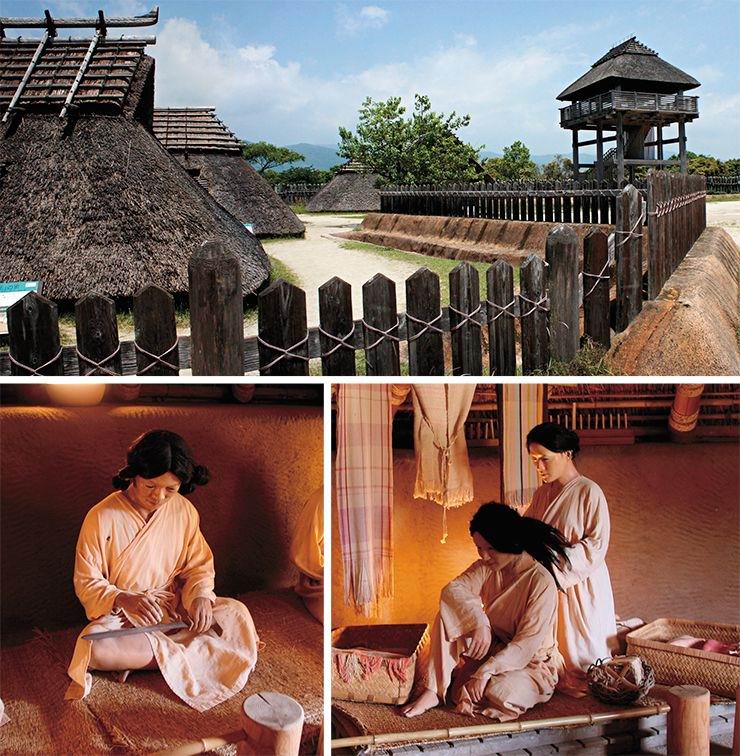

In the 1980s, in Saga Prefecture, the diggings of an ancient settlement dating to the Yayoy period (3rd c. BC — 3rd c. AD) started. Located on a hill at about 12 kilometers from the coast, Yoshinagari proved to be the largest Yayoy archaeological site: it included a few settlements or residential areas and was surrounded by a fertile plain. The results of the diggings were truly amazing both because of the massive size of the site and remarkable nature of the artifacts found here: a complex system of fortifications, a settlement, a cemetery, plenty of household items and weapons.

In 1992, it was decided to set up in Yoshinagari a historical park with the maximum possible number of historical reconstructions including not only residential and ritual objects and defense constructions but also plots of cultivated fields and ancient wood. In fact, a complete landscape reconstruction was made. For instance, under the metal structures erected over the funeral ground a spacious area has been restored under a mound. Coming inside, a visitor can see everything the archaeologists saw during the diggings.

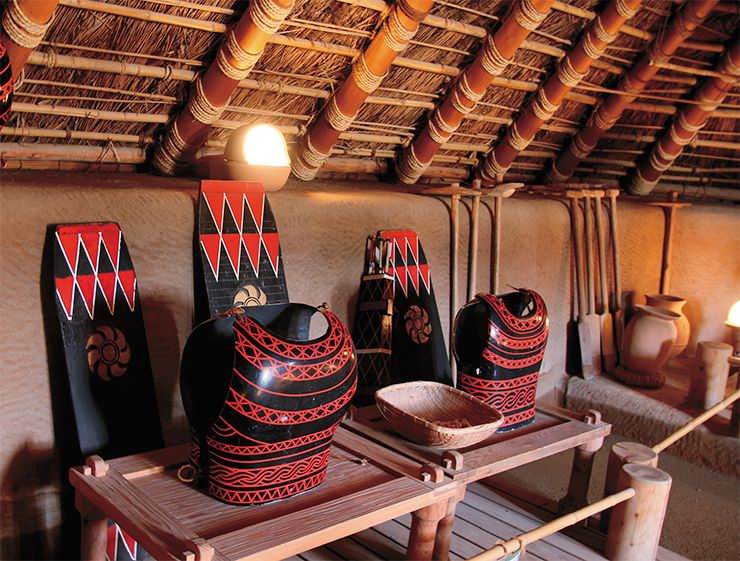

A visit to the historical park is a true journey to the past, which can take a whole day. You can go down the stairs to the semi-dugouts of regular community members and enter the houses of dignitaries; go to the top of watchtowers and outbuildings on piles; try on the armor and clothes of the time; and hold a sword or a wooden spade. Entire school classes come here together with the teachers in order to plunge into national history and engage in study activities.

It is sort of a “quest,” where young citizens must identify the objects, their purpose and the actors of the numerous historical reconstructions, draw up maps of the settlements, “deal with” the pottery handed out at the museum blocks, and so on. Workshops on making weapons, crockery, beads, etc., are held. As a result, every visitor feels the magic of this place and links to their ancestors who established the Japanese state, Yamato, “where the Sun goes heavenward, the world brings divinity resigning in it.” *

At the mound slope

Among the antiquities of the Japanese Islands the most famous and impressive, both in size and architecture, are the burial structures dating to the Kofun period (in Japanese, kofun stands for a burial mound). This is the time important for all the Japanese: it was then that the real ancient state of Japan emerged, as evidenced by the historical chronicles.

The colossal tumuli (mounds) are connected with the representatives of specific clans and dynasties, whose names are mentioned in documents. The historical parks set up around large mounds provide specific details. They inform the visitors in whose honor the mound was erected, what made this person famous and from what enemies he defended the land of their ancestors. Large mounds are considered not only a cultural heritage but rather as private burials having historical heirs including the representatives of the imperial house. It is one of the major reasons why research works, except for periodic restoration, are not carried out here.

Where ceremonies are performed,

There glitters a crystal clear mirror.

I can feel the ages long gone by…

The garden near the temple

Is swamped with fallen leaves

In Japan, small museums dedicated to the diggings of just one site are set up right next to it. Above it, they will often construct a pavilion, where the findings are exhibited and videos shown.

A spectacular example is the Hirabaru burial complex (early 3rd c.), based in Itokoku, north-east of Kyushu Island – one of the points where the Japanese statehood of the Yayoi period crystallized. In the largest mound surrounded by a ditch, a unique burial of a woman in a hollowed-out log was discovered.

In the burial pit, the archaeologists found plenty of jewelry, 40 broken bronze mirrors (the biggest was 46.5 centimeters in diameter and weighed 8 kg), and an iron sword put across the pit as though to lock it. This weapon was believed to be effective against afterworld forces, which suggests a sacred inner protection fence similar to the shimenawa rope in sumo. The buried woman must have possessed an outstanding magic power, which upon her death was dangerous for the living. Evidence to this effect is the broken - that is, deprived of their power – mirrors.

At the early stages of the development of human communities, the leader and minister of religion was usually the same person. According to the Japanese specialists, this woman-ruler could have performed some sacral functions connected with observing celestial bodies

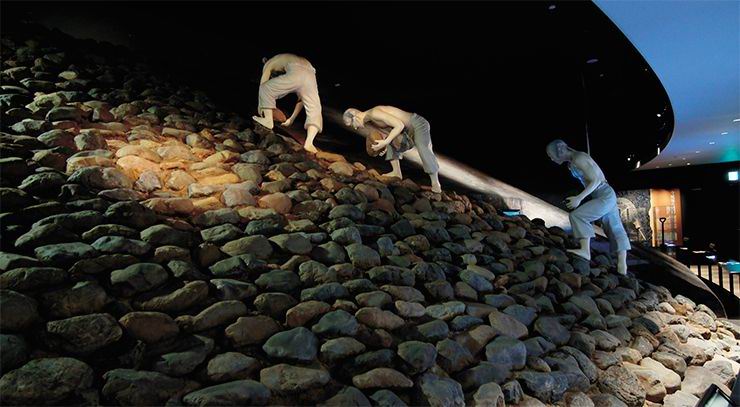

The tumuli are highly varied — from plain round dome-shaped structures of modest size to behemoth buildings fit for an emperor, from afar resembling mountains. The latter must be the largest burial structures in Asia. They can be 400 meters long, 300 meters wide and over 30 meters high. The area of their basement exceeds that of the main Giza pyramids but their height is lower. When you are standing near these structures covered with a dense canopy of trees and bushes, you can hardly believe they are man-made.

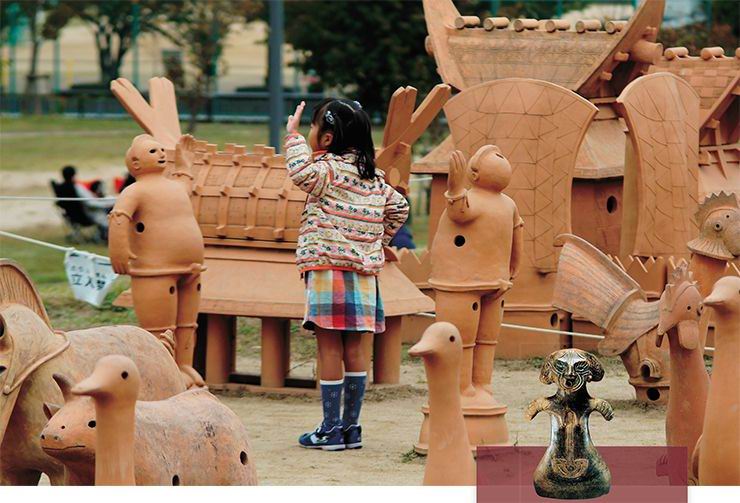

As a rule, you cannot go inside a tumulus. On some of them there are footpaths that will take you to the top. On the slopes of stepped tumuli there used to be Haniwa, terracotta clay figures. Along the perimeter of the tumulus and around it the Haniwa are shaped as hollow cylinders with big through holes in the sides. Their purpose is not entirely clear. There is a theory that they were designed to transport massive products with the help of a round perch put through the holes.

The anthropozoomorphic figures and artifacts depicting utility objects were grouped on special fields in strictly ranked lines. Though the meaning of these statues is ambiguous, it has been speculated that they might depict the so-called “road of spirits,” found in the Chinese and Korean burial structures of the dignitaries of high rank, including the Emperor’s.

The number of circular steps running alongside the tumulus depended on the status of the kofun’s “owner”: one or two for local aristocracy and three or more for the representatives of the imperial house. Geophysical methods, however, enabled the archaeologists to discover that not all of the burial mountains were handmade. Sometimes, a residual outcrop was shaped as needed and then a passage was made from a special patch close to the top to a burial chamber.

In West Japan, which did not have a strong state center, the burial mounds stood alone or in small groups on the hills or in the mountains.

In the regions where the state of Yamato that subjugated a huge territory was being formed, the tumuli are more impressive, over 200 meters long. As a rule, these mounds are located at the foot of mountains, which seem to protect them from one side. Most mounds are situated in the Nara valley (Nara prefecture) and in the Kawachi valley (Osaka prefecture), separated by a mountain range. All these mounds are connected with the names of historically authentic rulers, mostly emperors.

In the Japanese language, in contrast to Russian, the concept of time is less categorical. There is the past tense and the non-past tense, plus a multitude of grammar constructions specifying the details of doing an action. This may reflect the perception of time by the Japanese. Quite natural for them is the constant presence of events, phenomena and characters of the past in everyday life in the form of traditions, things and memorial places…Coming home from work which completely absorbs them today and by which they make the future, they change into a kimono and put on geta, paying tribute to the past. The past and the present co-exist in a unique way, hardly imaginable in the European world. All the parades, pageants and all sort of ethnographic villages that we come across in Europe are just a reconstruction of the past destroyed by a chain of wars and revolutions. In Japan, this is a continuous flow of being, intact despite all the cataclysms. The thousand-year-old living world is carefully protected from prying eyes and current concerns. Man and nature are one, and divine Amaterasu guards the country: “A huge wave rose up at the coast and stood up in thousands of rows, hiding the Yamato islands behind it!”***

*Song by Takahashi no Mushimaro, Japanese poet of the 8th c., Manyōshū collection of poetry, p.189

**From the Man'yōshū collection of Japanese poetry, 8th c. A mirror is a necessary attribute of a Shino temple, symbol of the Sun goddess Amaterasu, an emperor’s regalia, together with a sword and jasper pendants

***Song by Kakinomoto no Hitomaro, Japanese poet of the 8th c., Manyōshū collection of poetry, p.183

References

Laptev S. V. Contacts of the Japanese ancient population with the peoples who inhabited the territory of China before 6th c. AD. Moscow: Izd-vo Mosk. gos. un-ta lesa, 2003. 262 p., 24 ill.

Nakorchevsky А. А. Sinto (Shinto). St Petersburg: Peterburgskoye Vostokovedeniye, 2000. 464 p.

Plotnikov Yu. А. О naznachenii otverstiy v lopastiakh strel (On the purpose of holes in arrow blades) // Voprosy voennogo dela I demografii Sibiri v epokhu srednevekovia (Issues of Military Science and Demography in Siberia in the Middle Ages). Novosibirskк, 2001. P. 79–95.

Barnes G. L. State formation in Japan: essays on Yayoi and Kofun period archaeology. New York; London: Routledge Curzon, 2003. 256 p.

Mizoguchi K. The Archaeology of Japan: From the Earliest Rice Farming Villages to the Rise of the State (Cambridge World Archaeology). Cambridge University Press, 2013. P. 393.

Mizoguchi Koji. The Yayoi and Kofun period of Japan // Handbook of East and Southeast Asian Archaeology (eBook). N. Y.: Springer, 2017. P. 561–602.

Yoshida H. Nippon retto:-niokeru bukikeyseydo:ki-no chujokaisi nendai (Time when bronze weapons began to be made on the Japanese Islands) // Higasi Ajia seido:ki-no keifu (Bronze Weapons Genealogy in East Asia) / Ed.: Harunari Hideji, Nishimoto Toyohiro. Tokyo: Yuzankaku, 2008. P. 39–54.

The photographs used in the publication are the courtesy of the authors. Research was supported by the RFBR (grant # 18-09-00507)