Faces from the Past

Finds with the images of people who crossed the “great divide” are some of the most exciting for the archaeologists. The ones found in the Noin Ula mountains in Northern Mongolia in the burial mounds of the Xiongnu elite allowed us to see real participants of historical events which took place two thousand years ago. It helped us to discover another aspect of life in this remote era, which has already become legendary

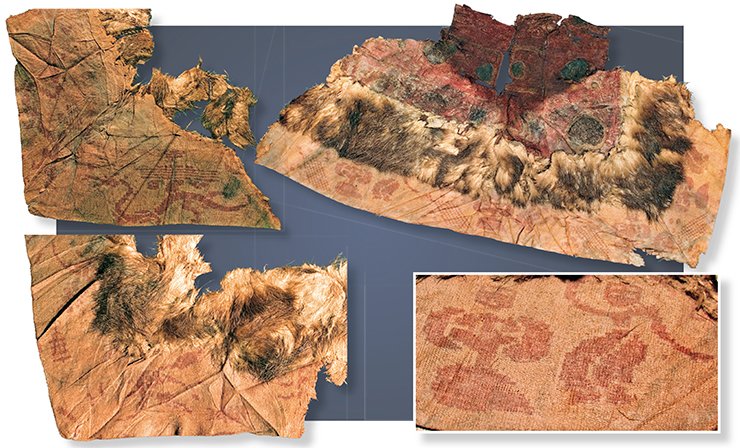

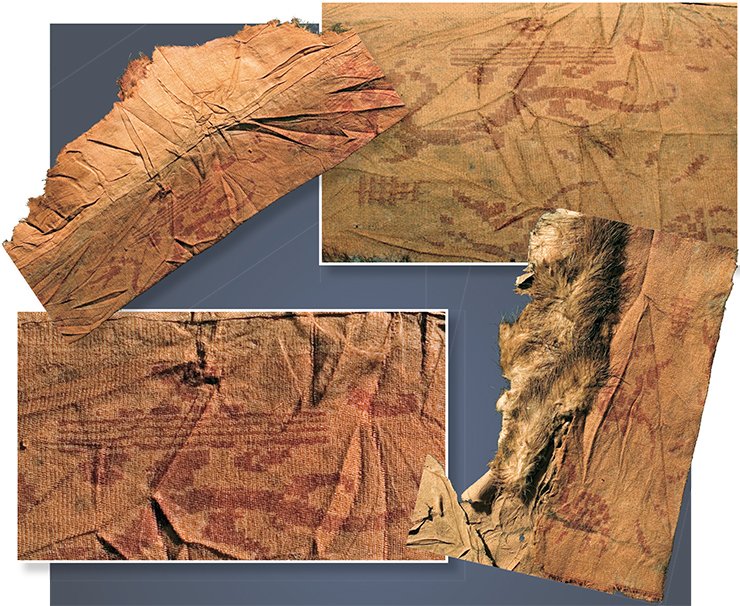

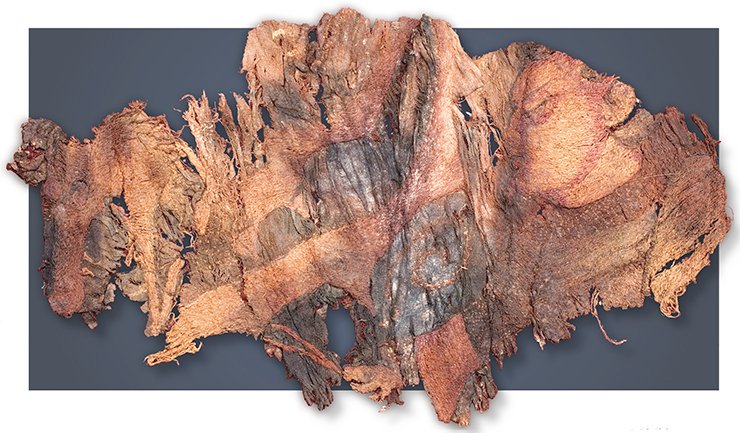

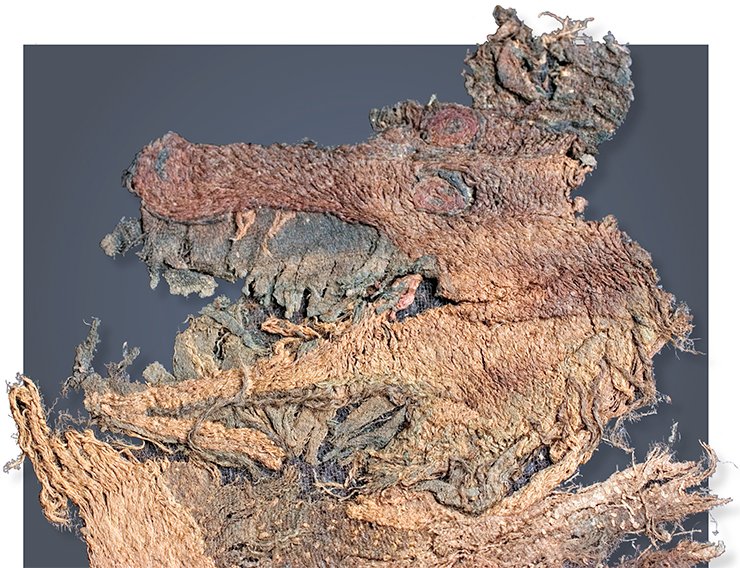

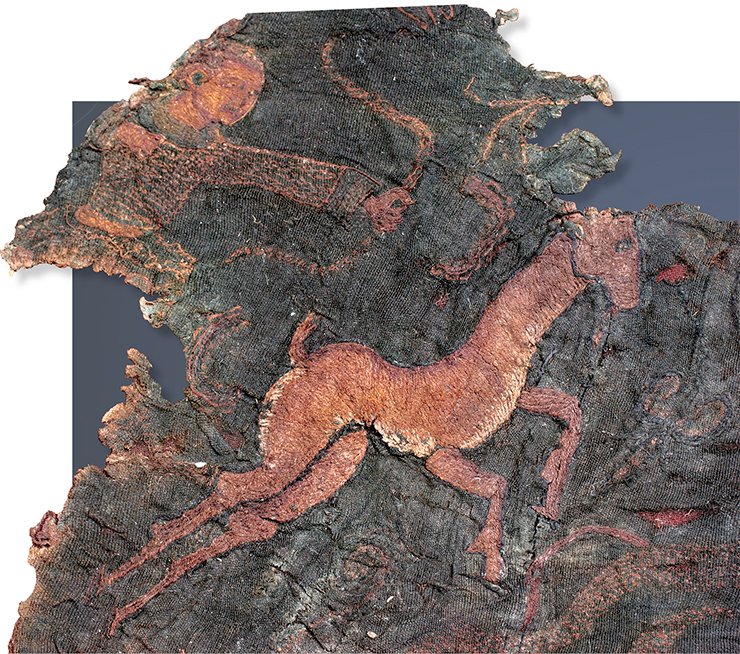

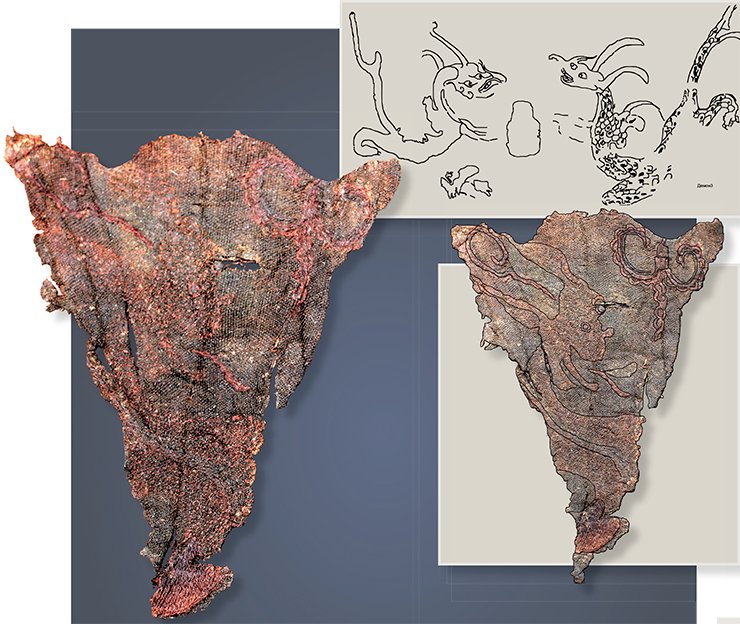

In Noin Ula mound 20 (North Mongolia), along with many unique objects fragments of outer garments were discovered. They were found buried in water and clay at the bottom of the looted burial chamber. These fragments present several relatively large pieces of the garment’s lower flap. It is as yet impossible to determine whether it was a short rider’s jacket or a long caftan, but it looked splendid.

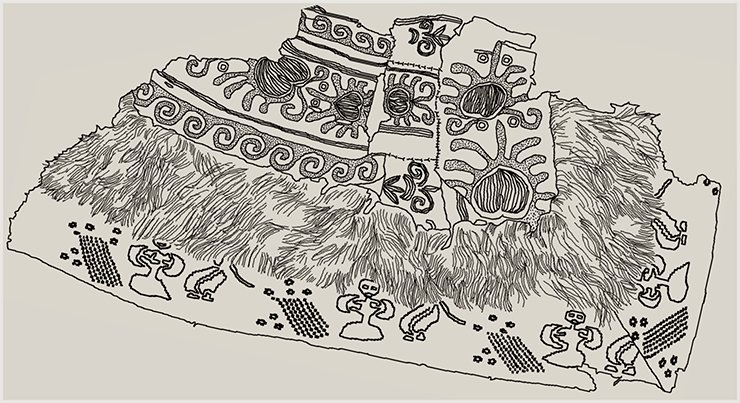

A thin, dense sand-coloured silk fabric made up the basis for the dress. A thin layer of silk wadding was placed between the silk basis of the clothes and their smart decoration from embroidered wool and silk fabric. Silk flaps from double folded pieces of light beige fabric with strips of repeated pattern embroidered with red threads, which included the image of an ancient hieroglyph, were sewn on the edges and hem.

Revelations of Fu Xi, the first of the Five sheng legendary rulers of the antiquity

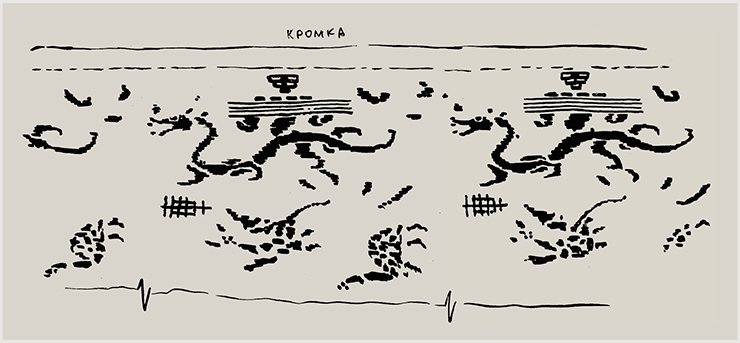

The pattern on the silk fabric edging the outer garment is unique. Red images of walking dragons and a snake-legged man standing behind them are embroidered on sand-coloured silk. Four parallel lines “lie” in his bent arms. In another plane the images of a tortoise and Phoenix can be seen. On the other cutoff piece of fabric images of a dancing man and woman are embroidered.

According to the Taoist tradition, crimson, red and cherry red colours are used to depict heavenly personages, phenomena and the objects of the “higher world” (Kravtsova, 2004). Traditionally it is considered that the “Azure Dragon”, the guardian of the East, the White Tiger, the guardian of the West, the Cinnabar bird, the guardian of the South, and the snaky Black Tortoise, the guardian of the North, comprise the four guardian spirits. Each of them is located in its own part of the image corresponding to one of the cardinal directions. Such ornamental motifs were often used on edge tiles, mirrors, burial frescos and coffins during the period of the Han Dynasty. These animals are associated with the Taoist Land of the Immortals, with the mountains always considered their abode. It is not without a reason that the hieroglyph for the immortal Xiang is designated by the graphemes “man” and “mountain”. The ancient hieroglyph 崋 – hua repeated on fabric consists of two elements: 華 – hua meaning “blossoming”, “prosperous” and 山 – shan meaning “mountain”. The hieroglyph depicted on the material does not fully coincide with the given printed version. The reason for this is that that the hieroglyph is embroidered, not written, which has resulted in its slightly altered shape. Besides, the Chinese language is characterized by homonymy: interchangeability of hieroglyphs which sound the same but are spelt differently. The hieroglyph discussed here has several meanings: a) the name of the mountain; b) The Hua Shan Mountain (The Great Flower Mountain); c) family hieroglyph Hua. The Hua Shan Mountain is one of the five sacred Taoist mountains in China. This meaning of the embroidered hieroglyph is preferable, taking into account the depicted composition as a whole (the hieroglyph was decoded by Candidate of History A. Chistyakova.)

In this magic “heavenly” surrounding, the figure of the snakelike man standing by the dragon is the most interesting. It can be safely assumed that what we see is the image of Fu Xi, the first of the Five sheng legendary rulers of the antiquity. This culture hero, who taught people to hunt, fish and manage fire, was extremely popular during the Han Period. Eight trigrams from three continuous and dashed lines are considered his major contribution: the continuous line represents Yang and the dashed one, Yin. They were brought to his eyes in the drawings on the shell of a magic tortoise, which emerged from the Lu Shui River (in one version), or in a hair curl on the back of the dragon horse, which emerged from the river Huang He (in another version). The image embroidered on the cloth reflects very well the last version of the story of how the trigrams emerged. From these trigrams, which serve as the key to the sacraments of natural and social phenomena, the fortune-telling practices, medicine and geomancy originated (Ermakov, 2008). They formed the basis for I Ching, the primary book of Chinese occultism.

In the hands of the heavenly ruler woven in the cloth from Noin Ula there are four lines, not three. It seems that this interesting fact can be explained as follows. Confucians, who adopted I Ching many years after the death of their teacher, (in the opinion of Yu. K. Shutskiy, the most outstanding Russian researcher of this text, it happened between 213 and 163 BC) not only studied the Book of Changes but sometimes even imitated it. Such is the Book of the Great Mystery (Tai Hsuan Ching) written by Yang Tsun. This unsolved text also contains symbolic linear figures similar to those The Book of Changes contains. Only in this case the figures are comprised of four lines each: unbroken, dotted and double dotted (Shutzkiy, 1997, p. 222), which corresponds to what we see in the Noin Ula ornament.

It is known that the images of Fu Xi with Bai Hua shown by eight trigrams appeared only in portraits of the late Middle Ages. Hence, the engraving in the Comprehensive Mirror of the Immortals (Zhenxiantongjian) shows Fu Xi with the emblem of Bai Hua which he holds in his hands pressing it to his tummy. The image of Fu Xi depicted as a man with symbolic linear figures embroidered on the fabric discovered in Noin-Ula mound 20 is the most ancient among those presently known. The silk fragment used for facing the smart nomad clothes presents a unique sample of fabric of the Han period.

It was followed by rather narrow fur flaps, most probably from sable; its fur is shiny, soft and fluffy of beautiful dark brown colour. Next, there was red woollen fabric with embroidery made using woollen threads.

Above it silk fabric was sewn, consisting of pieces sewn together as well. It is a miracle that these small silk fragments had been preserved: very thin and fragile fabric with embroidery turned to ashes in front of our very eyes, but what has survived presents a real treasure.

What has survived presents a real treasure

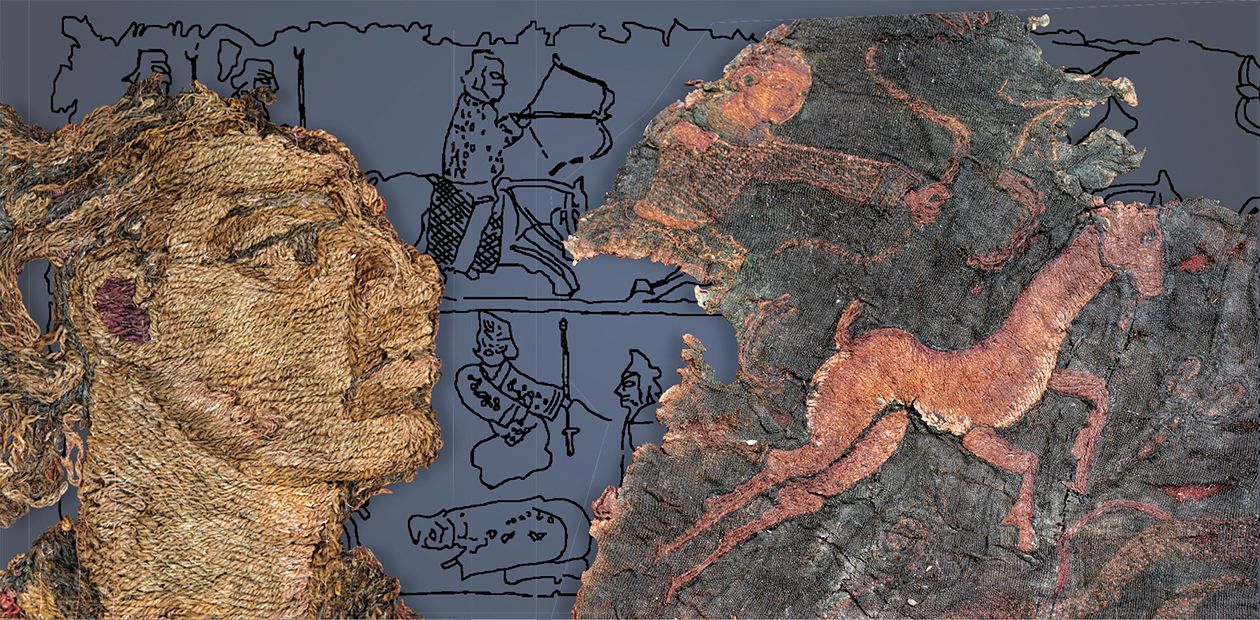

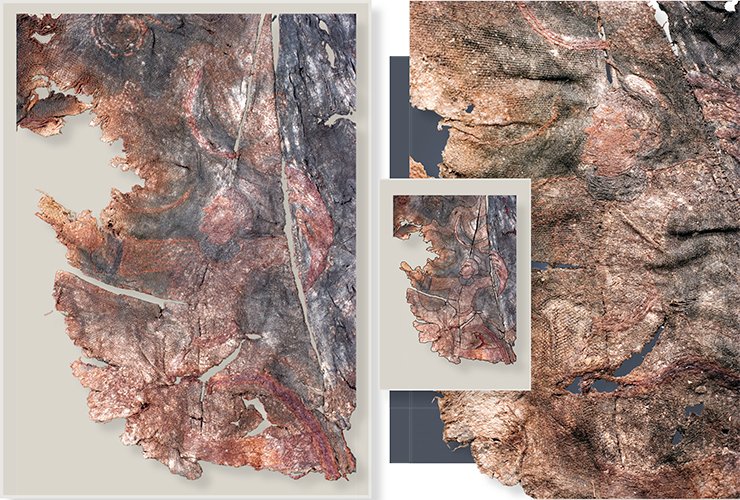

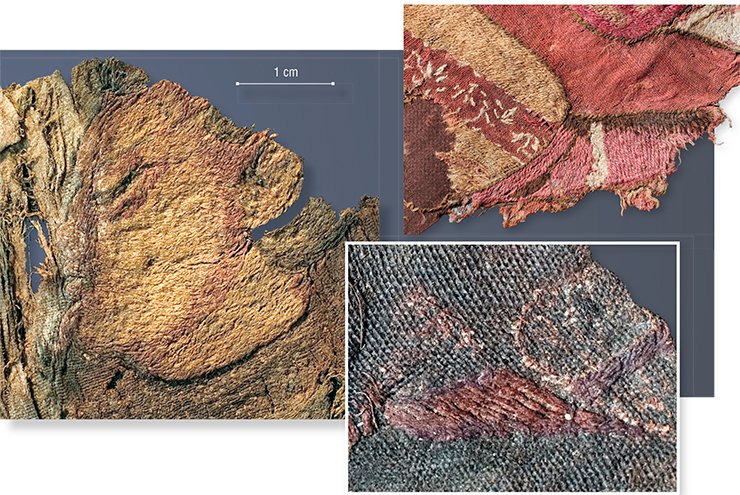

The embroidery on silk is of great interest. Initially, it could be a part of a common composition, but the separate fragments that have survived to the present can hardly help to restore the complete picture. The embroidered images are very small, and their condition is such that it is extremely difficult not only to examine them closely but even to see them. Nevertheless, photos of everything that was possible to be photographed were made in the process of carrying out the study and can be used for work.

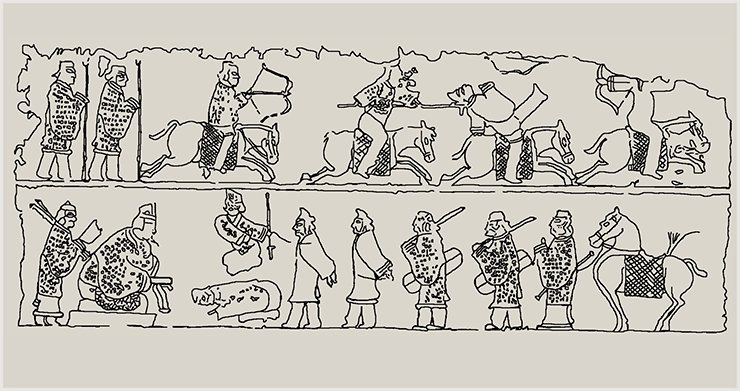

Images of warriors and hunters, mythical and real animals surrounded by signs and symbols are embroidered with silk threads on silk.

Fragments with the images of five men, each of whose faces bears its original features and do not look alike, have been preserved. Two of them have strongly pronounced mongoloid features.

Fragments with the images of five men, each of whose faces bears its original features and do not look alike, have been preserved. Two of them have strongly pronounced mongoloid features.

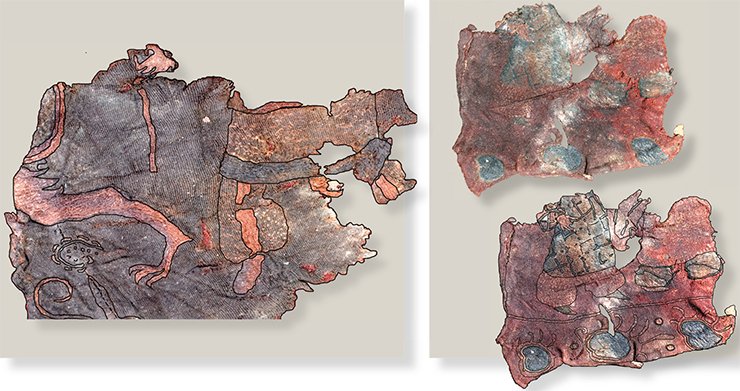

One of them, with a very expressive plump face, is drawn from the left side. The man has plump lips, a protruding low forehead, and a slightly crooked nose with a meaty, rounded, slightly snubbed end; a half-closed eye stretched towards the temple and a long thin brow under it; a short thick neck or rather an almost complete absence of it and a small narrow beard, which, as can be seen, grows from under the lower lip because the chin is fully outlined. Such type of beard is known from the images on Han patterns. Overall, it is hard to judge the haircut, but what can be seen is a characteristic high temple pointing to the hair tied in a bun and an ear and dark hair on the neck behind it.

The man is dressed in a closed garment with long sleeves widened towards the bottom, which is typical of the Han dress, with a wide piped edge round neck designated in a different colour and texture. The same horizontal strip of trimming can be spotted in the upper part of the sleeve. In his right arm, extended forward, the man holds an object which looks like a bifurcated stick. The man’s head is turned towards the image of a mythical dragon-like animal, in whose direction his arm is probably extended. Only the bare teethed stretched muzzle with close-set round eyes with embroidered pupils has been well preserved. In the Chinese art of the Han period, horse-dragons looked like this. It is probable that the fragments of the embroidery that have been preserved between the figure of the man and the animal muzzle could be part of this creature’s body. Free space of the dark silk fabric between the embroidery and the man’s right hand is occupied by the image of the right twisted spiral. On threadbare silk the continuation of belted clothes can be traced with considerable difficulty.

The man drawn from the right side also has a plump round face similar to that of the first personage described above. This personage is almost neckless, with thick black hair with the same characteristic cut by the temple. The hair is tied in a round bun high at the back. Probably, a long hairpin stuck into the base of the hair bun is embroidered in brown thread. Attention is drawn to narrow-cut eyes and a thin brow progressing to the temple. The man casts an upward glance; he has a rather small nose comprising a single line with the low retreating forehead and plump lips. It is possible that this personage’s face suffered some damage: probably it wore a beard.

The man is dressed in a closed garment, with the tight fit waist running to the hip. A broad strip shown in a different colour and texture edges the round neck. The same kind of strip runs along the upper part of the right sleeve and passes onto the chest broadening towards the bottom. The same fabric edges the wide sleeve cuff, with the bottom part of this garment and trousers sewn from the same fabric. Probably it was the way to depict combined clothes made of leather and fabric. Thus, leather could be depicted by smooth embroidery in sand brown shades, while the cloth could depict the neck and sleeve cuffs edging. An interesting detail should be pointed out: the garment’s broad sleeve is covered in angled checkers. Usually in fine arts, for example, in Khalchyan sculptures, on the coins of Indo-Parthian rulers and in Parthian embroidery, rectangular checkers depicted armour consisting of tightly sewn metal plates. It is known that early Chinese armour was made of lacquered leather plates (finds from Leigudun, Hubei province, in the state of Chu, 433 BC – M. V. Gorelik, 1987).

Probably, this pensive man sits on the mythical dragon horse; part of the animal’s back covered in a row of parallel strips resembling a tiger’s hide can be seen.

According to Li Po famous dragon horses look as follows:

The heavenly horses originated from

The caves in the land of Yuezhi

With a pattern like that of the tiger on their backs

and the body complete with dragon wings.

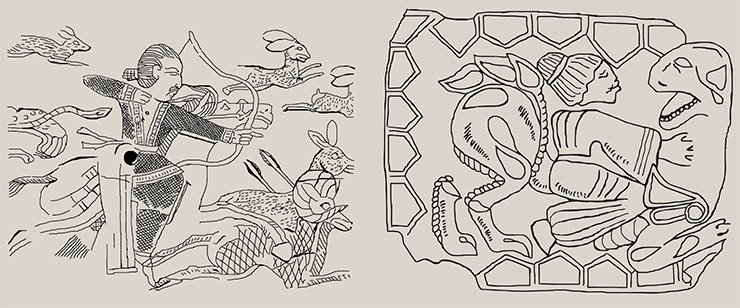

The images of hunting riders on the Takhti-Sangin ivory plate present the closest analogy to this image. Noticeable resemblance can be seen in the profile images of broad-faced, round-headed images. At the same time, there are considerable differences between them as well. There is no certainty that the rider in the embroidery has a moustache. Also, even though it seems that both personages have similar haircuts, with high temples and hair tied in a bun, the buns themselves look different. In the embroideries men with thick round buns of hair pinned with a long hairpin high at the back, almost at the back of the head, can be seen, while on the Takhti-Sangin plate a bun of hair looks like a small “cylindrical” edge low at the back. Besides, as opposed to the embroidered images, Takhti-Sangin riders on the buckle are dressed in traditional Iranian dress, i. e., open girdled short jackets leaving the chest open.

The images of hunting riders on the Takhti-Sangin ivory plate present the closest analogy to this image. Noticeable resemblance can be seen in the profile images of broad-faced, round-headed images. At the same time, there are considerable differences between them as well. There is no certainty that the rider in the embroidery has a moustache. Also, even though it seems that both personages have similar haircuts, with high temples and hair tied in a bun, the buns themselves look different. In the embroideries men with thick round buns of hair pinned with a long hairpin high at the back, almost at the back of the head, can be seen, while on the Takhti-Sangin plate a bun of hair looks like a small “cylindrical” edge low at the back. Besides, as opposed to the embroidered images, Takhti-Sangin riders on the buckle are dressed in traditional Iranian dress, i. e., open girdled short jackets leaving the chest open.

In men’s haircuts Chinese analogies can be spotted. To compare, among the haircuts of the Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi’s clay army warriors similar-shaped haircuts with buns on top of the heads have been found. The Dien bronze personages wear similar haircuts. This is quite a significant fact because the so-called “riders’ set” in the culture of Dien (clothes, arms, haircuts) are associated with the Central Asian horse riders. Another image resembling the embroidered ones is depicted on the badge from Kochkovatka (See Fig. p. 101).

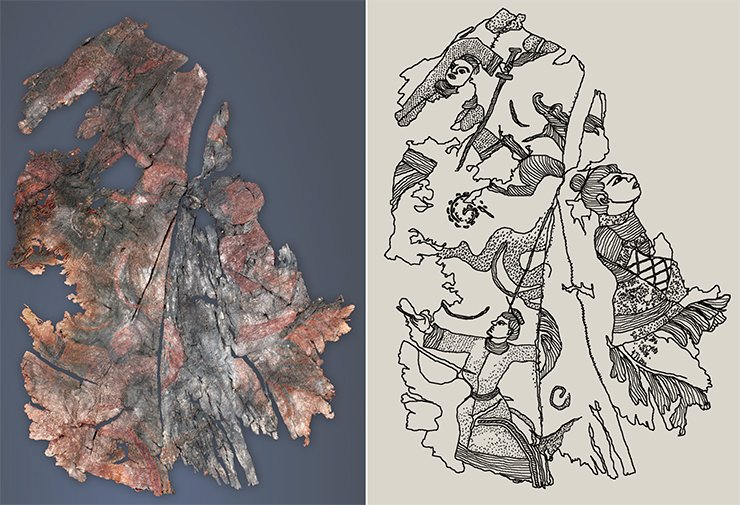

The next personage is drawn from the left. The man has a long thin face, a haircut with a large oval bun of hair on the crown of the head and a characteristic cut by the temple. He has a large straight nose, an almond-shaped eye and a low forehead with the overhanging super-front; his glance is directed straight in front of and slightly up from him. He is dressed in the same open clothes tightened with a belt as the rest (with what appears to be a cut being a seam in the fabric). His right arm with an open palm up is extended forward. The left arm is extended in the opposite direction and can be traced to the elbow; after that there is a seam followed by an ornament not connected with the one described above.

Above this image the back part of a zoomorphic figure with a bent body and a long tail can be seen. Near it there is a festive curl which is repeated many times among other images on this article.

The fourth image is that of a man of Caucasian origin, shown full-face. The man has big eyes and a snub nose. His right arm goes behind the back, clasping a long sword in his arm ready for a blow. The sword pommel is shown T-shaped in the embroidery. The warrior clasps the long handle closer to the cross-guard which looks straight; it was, of course, impossible to show details of the sword in such small embroidery. The left arm is drawn back, and a broad sleeve cuff can be seen. A nine-tailed fox, a heaven dweller, depicted in the Han bas-relief from the Shandong province is pierced by such dagger. Behind the man’s back part of the trunk and possibly muzzle of some mythical animal can be distinguished.

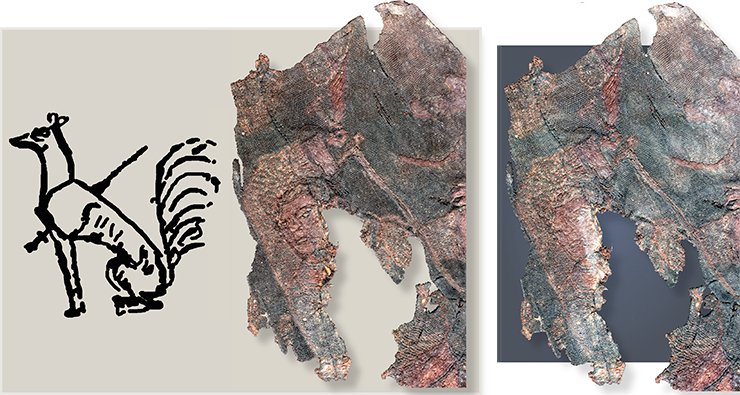

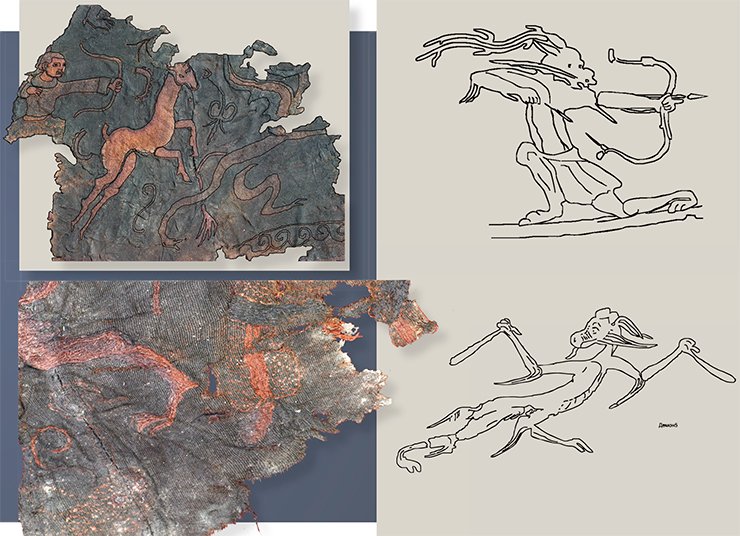

The fifth and the best preserved personage on the embroidery is that of a hunter whose head is shown in three-quarter view. It’s a man of Caucasian origin, with a young and round face, a low forehead and almond-shaped eyes below a straight line of eyebrows. The haircut is similar to that of the other personages in the embroidery: the hair is combed back forming a horseshoe-shaped cut by the temple. Probably, the man had the same bun of hair on the top of his head as the other personages in the embroidery. The closed clothes are identical to those described above. The man stretches the bowstring aiming at a roe in a jump positioned straight in front of him.

The bow is a composite one, similar to those of the riders on the Takhti-Sangin plate . The embroidered hunter has a different manner of holding the bow and drawing the string. His left arm stretching the bowstring is at the chest, not at the neck level as is the case of the Takhti-Sangin plate. The spirit protector in the painting in the second sarcophagus of Lady Dai from the burial in Mawangdui 1 (168 BC) stretches a composite bowstring in the same way while sitting down on one knee. All the space around the hunter and roe is filled with signs-symbols. These are two semicircles resembling horns at the roe’s back. An S-shaped symbol is embroidered below the roe. Above it three twigs of some plant are embroidered and higher still a clawed paw of a predator. Right in front of the roe there is a monogram or a flower and the image of some mythical creature going away, probably with a wing, on two three-pawed legs, a long bare tail ending in a bun (its head has not preserved). The dragon-like animal embroidered in silk resembles the images from the second sarcophagus of Lady Dai from Mawangdui-1. In the opinion of some researchers, the paintings on the second coffin show the transition of the deceased into the other world where she is met by the zoomorphic creatures of spirits protectors with the attributes of warriors and spirits guardians (Kryukov et al., 1983).

Apparently, the embroidery on silk from Noin Ula mound 20 was very populous: besides human figures with preserved faces and body parts, several images of legs were discovered as well. That is all that has been preserved from the images of those they belonged to.

Over the man with the sword, for example, right above the hand clasping the handle, part of the leg can be seen presenting an elegant foot in soft footwear and part of wide trousers with a vertical strip of trimming. Two legs dressed in the same kind of trousers, wide at the bottom with a vertical strip of trimming on each of the trouser legs, can be seen in another fragment. The soft footwear hidden below the knee level under the closed outer garment with wide edging over the bottom flap is also visible. Also preserved of this personage is the embroidered right hand wrist holding some object.. It seems that the man follows a mythical animal running away. A very large bird’s leg with three claws and feathering in the upper part has been preserved of it. Lower, another monster is embroidered; this is a dragon-like creature with round eyes, horns, wide open jaws and a long, narrow, protruding tongue. The same kind of creature has been preserved in another fragment of fabric, with S-shaped signs-symbols embroidered above its muzzle characteristic of this kind of material.

Such depictionss of legs, wearing wide trousers gathered at the ankle covered by square armour plates below the knees, have been preserved on the fragment of wool fabric from the same article (see Fig. P. 107).

Who is embroidered in threadbare silk?

The great charm of this find derives from the reliable dating of the burial mound from which it originates: the end of the first century BC - the beginning of the first century AD, most probably, the first decade of the first century AD (Chistyakova, 2009, pp. 59—68; Minyaev, Elikhina, 2010). That is why the main questions are who made the embroidery, where these fragments were made and who is depicted in it.

The men are dressed in special kind of clothes. These are not nomad jackets, robes, caftans or armour in the way we are used to seeing in other images that have been preserved from the past. Their costumes are very unusual, which is rather hard to find an analogy to despite their simplicity. In the clothes’ upper part some similarity with the dress of horsemen and charioteers from the Emperor’s Qin Shi Huangdi’s clay army soldiers can be spotted. At the same time, the trousers and shoes are not Chinese and most likely belong to nomads, though maybe after the law adopted during the rule of the Emperor Zhao Yu Liang (307 BC), some part of the Chinese population, horsemen warriors, started to wear barbarian clothes: trousers and shoes. Besides, barbarian horsemen who served in the Chinese army continued to wear their traditional clothes. Overall, the suits in which the embroidered personages are dressed are quite original.

Men embroidered on the silk share some common features. Besides being dressed in similar suits, they have common haircuts, with round buns of hair almost on the crown of their heads probably fixed with a long pin. It is known that the Chinese of the Han period did not cut their hair but set it on their heads, pinning it down (Kryukov et al., 1983). The faces of the warriors differ but when you look at the Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi’s clay army warriors, you also see a great variety of faces. However, all ten types of soldiers and officers singled out by the researchers are Chinese and belong to the Mongoloids from the Pacific group, while among the personages embroidered on the silk there are two with Caucasian features. Such a diversity of face types can reflect the actual historical situation.

Who is then embroidered on the decrepit silk? There are weighty reasons to assume that these are Xiongnu. The outer garment is sewn from different patches of material fragments of which were discovered in the burial of and belonged to a noble Xiongnu. It could be made to order and reflect his taste. Had it been a ready-made article produced in the Han shops, which were often given as gifts to the chányú, it could hardly have consisted of small pieces of wool and silk first stitched together and then embroidered. A combination of the Chinese and Barbarian features (in this case Iranian) in the dress and haircut of the embroidered personages can attest to the fact that the artisans copied the images of people they saw around them, possibly the representatives of the Xiongnu elite. As can be seen from archaeological finds (robes and trousers from Noin Ula mound 6) and the combination of presents given by Han court to the chányú, which included not only fabric and silk wadding but also ready-made clothes, the dress of the latter combined the articles of clothing of Chinese origin, own production and borrowed from other sources, for example, from nomads of Iranian origin.

It is known that other peoples were also represented at Xiongnu sites. More frequently these were the Chinese; sometimes military commanders from among the defectors and the captives, menials accompanying the wives of the Chinese chányú and probably skilled craftsmen. The Xiongnu Empire united or spread its influence over many tribes and peoples of Central Asia, Southern Siberia and Eastern Turkmenistan. Their representatives were not uncommon among the chányú circle.

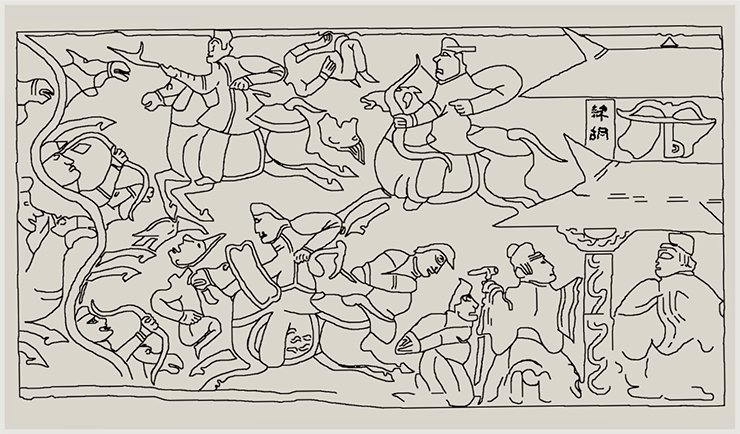

What is particularly important is that in this case what we see is not a generalised image of an enemy which was how the Xiongnu were depicted on the Han reliefs but the real people. They are incorporated in the context of mythological narrative created by the Chinese craftsmen according to the Chinese tradition.

The embroidered fragments show the other world filled with traditional Chinese zoomorphic spirits-protectors and spirits-guardians fighting with some mythical creatures. Among them are warriors and hunters, who in the given context present semi mythical personages themselves. On the whole, this embroidery presents a typical Chinese Taoist concept of the afterworld (Birrell, 2005).

Attention is drawn to skillful work: the images embroidered on the silk are very small. Only the Chinese masters of needlework are known to have been capable of such tedious work. Most probably, the discovered embroidery is of Chinese origin, but was created under the influence of needlework of western artisans. Such wonderful images could be created using embroidery in wool, which was well-known to both Xiongnu and the Han. Embroidered Parthian wool curtains were discovered in the Noin Ula mound (SCIENCE First Hand, 2010. V. 3 (33); 2011, V. 2 (38), in Russian).

It is well-known that in ancient China Parthian tapestry fabric and carpets as well as carpets and bedspreads from the Syrian weaving factories were highly valued (Lubo-Lesnichenko, 1994). Many such articles found on the Silk Road and in the burial mounds of the Xiongnu elite support the data contained in the written sources. These articles not only decorated the interiors of the Han nobility houses and palaces but also became the models to be emulated.

The manufacturing techniques and means of depicting faces and clothes on the embroidery on silk under discussion is identical to that on wool curtains discovered in Noin Ula mounds. It is enough to have a look at men’s faces depicted on the curtain from the Noin Ula mound 31 and on silk from mound 21 to see that the artisans used the same techniques to make the embroidery. The size of images embroidered on silk is considerably smaller than that of the depictions embroidered on wool: if the size of faces embroidered on wool reaches 9 cm, then the size of the largest face embroidered on silk did not exceed 3 cm. Overall, small and frequent pattern both embroidered and woven is typical of the ancient Chinese textile. During the rule of the Tang dynasty a ban on producing certain types of patterned multicolor fabric (771) was imposed because laborious work on it “was harmful for the artisans” (Shefer, 1981. P. 263).

Thus, most probably the embroidery on silk decorating the Xiongnu clothes fragments which were discovered in Noin Ula mound 20 had been made by the Chinese artisans working at chányú court inspired by the embroidered curtains of the Parthian masters they saw. Several fragments of silk on which the image from the embroidery on woolen clothes is repeated can be considered as a proof supporting this hypothesis. The images of people embroidered on silk came as a result of the Chinese artisans’ familiarity with the examples of “western” art and probably not only the textile but also some other articles of superb artistry which the Xiongnu had in abundance.

From the ancient times, the Chinese art was open to foreign influence which concerns textile production as well. During the Han period, patterns of the Middle Eastern origin started appearing on fabric: figures in closed space, riders at a “flying” gallop, with the heads turned back, etc. (Lubo-Lesnichenko, 1994); in the Tang period excellent silk fabric with embroidered images and plots characteristic of Sassanid Iran was produced in China (Shefer, 1981).

Probably, when producing festive clothes from fabric at hand, the Chinese artisans created original embroidery combining the traditional Chinese motifs with the artistic and technical techniques of the Western artisans. Thanks to this, a unique piece of ancient art was created.

Аrchaeological findings of portraits of people long gone into the other world – faces from the past – are some of the most exciting discoveries made. What we were lucky to see on the threadbare cloth was born thanks to the talent and fantasy of an unknown Chinese artisan who by some quirk of fate found herself in the Mongolian steppe among the Barbarians. Until now, images of people embroidered on silk have not been known among ancient Chinese textiles. Techniques of drawing the personages under consideration, their postures and gestures copy the figures embroidered on imported wool fabric. The latter though served only as an example for the creation of absolutely original depictions of the “masters of the steppe”.

References

Ermakov M. E. Magija Kitaja. Vvedenie v tradicionnye nauki i praktiki. SPb.: Azbuka-klassika; Peterburgskoe Vostokovedenie, 2008. 192 s.

Kravcova M. E. Istorija Iskusstva Kitaja: Uchebnoe posobie. SPb.: Lan’; Triada, 2004. 960 s.

Lubo-Lesnichenko E. I. Kitaj na Shelkovom puti. ¬M.: Vostochnaja literatura, 1994. 326 s.

Minjaev S. S., Elihina Ju. I. K hronologii kurganov Noin-Uly // Zapiski Instituta istorii material’noj kul’tury RAN. SPb, 2010. № 5. S. 167—181.

Chistjakova A. N. Perevod ieroglificheskoj nadpisi ¬na lakovoj chashke iz dvadcatogo noin-ulinskogo kurgana // Arheologija, jetnografija i antropologija Evrazii. ¬Novo¬sibirsk: Izd-vo IAJeT SO RAN, 2009. №3 (39). S. 59—68.

Shuckij Ju. K. Kitajskaja klassicheskaja «Kniga peremen». M.: Vostochnaja literatura, 1997. 606 s.