The Vivid Colors of Merian

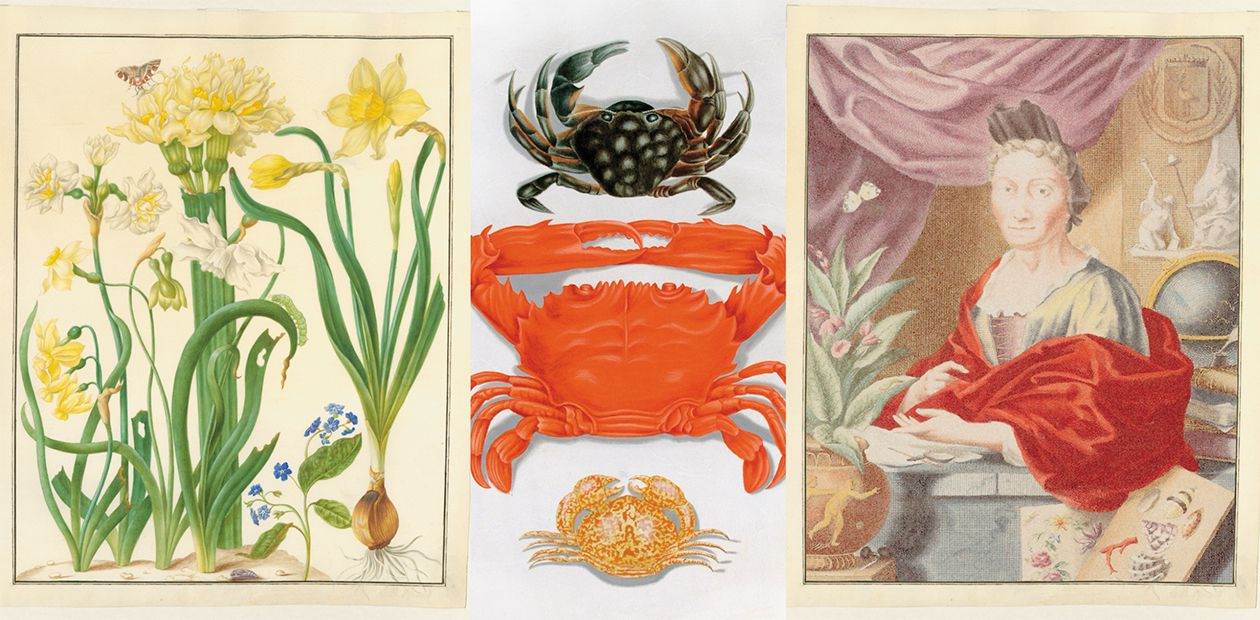

For the 17th and 18th century scholarly studies, drawings were so important that they should be regarded not as mere illustrations but as part of scientific investigations. The Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg keeps remarkable water-colors that continue to attract the attention not only of art historians, but also of botanists and etymologists. The librarian of the Imperial Academy of Sciences J.G. Bakmeister wrote in his book about the library and Kunstkamera that "Worthy of particular attention of connoisseurs are the marvelous miniature paintings of flowers, worms, and other insects made on special vellum sheets by the glorious Maria Sybilla Mariana with an extraordinary taste and consideration."

The name and work of Maria Sybilla Merian are known in Europe, Japan, and America, and the interest in her life and art has been growing. In Europe, in the recent years, exhibitions devoted to Maria Sybilla's creative work have been organized, and her books have been republished. But the fate of Maria Sybilla water colors in Russia is such interesting and complicated that every new find or new treatment of known facts creates a desire to share them with readers

For the 17th and 18th century scholarly studies, drawings were so important that they should be regarded not as mere illustrations but as part of scientific investigations. In the works of the time, images would often display not only the object of study but the process under examination as well. Also, illustrations had a great practical value. For example, the magnificent catalogue of the Indian Ocean fishes “Histoire naturelle des plus rares curiositez de la mer des Indes” (1718—1719) by the Amsterdam publisher and politician Louis Renard contained information of paramount importance for the marine nation: which of the fishes were edible and which were poisonous. Artists had to satisfy high requirements: not only did they have to possess a great artistic talent but also to obtain deep insight into the things they depicted. Of no less importance than exact depiction of an object was the choice of colors. One of such remarkable illustrators was Maria Sybilla Merian, an artist and investigator whose watercolors captured the amazing world of animals and plants

The Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg keeps remarkable water-colors that continue to attract the attention not only of art historians, but also of botanists and etymologists. The name and work of Maria Sybilla Merian are known in Europe, Japan, and America, and the interest in her life and art has been growing. In Europe, in the recent years, exhibitions devoted to Maria Sybilla’s creative work have been organized, and her books have been republished.

A brilliant study of the artist’s creations and narration about her no easy life was written by the well-known science historian T. A. Lukina.1 This is a reference book for everybody who examines Maria Sybilla’s watercolors in Russia. The author of the present article is no exception: she quotes Merian’s works translated by Lukina and makes frequent references to her book.

The destiny of Maria Sybilla’s water-colors in Russia, however, is so exciting and intricate that every new finding or new interpretation of known facts urges us to share it with the readers.

Daughter of an artist

Maria Sybilla was born on April 2, 1647 in Frankfurt on the Main. Her father was a well-known Swiss artist and engraver M. Merian; the girl was brought up and taught to draw by her stepfather, the Dutch artist J. Marell.

At the age of seventeen Maria Sybilla married J.A. Graaf, also an artist and a student of Marell’s. Maria Sybilla’s family life was not happy though. In fact, the husband and wife parted in 1686, when Maria Sybilla was nearing her 40th anniversary.

Merian, who took back her father’s name, joined the sect of Labadists and settled with her mother and two daughters in Walta Castle, West Friesland. Five years later, she moved to Amsterdam. In 1699 the artist, together with her daughter Dorothea Maria, went to Surinam, where she stayed for two years.

Maria Sybilla Merian died on January 13, 1717, in Amsterdam, after two years of a serious disease.

...Even a mere citation of biographical facts tells a good deal about this woman, whose life was not easy and quite outstanding, especially given the time she lived in, the 17th and early 18th centuries.

Maria Sybilla was brought up in artistic surroundings: her father, stepfather, and brothers were artists... In her childhood, she mastered the technique of copper engraving and helped her mother with silk embroidery for sale.

They used to embroider with silk threads of their own production: white mulberry trees grew in the garden; the silkworms were raised, fed, and sorted by the family members. It must have been then that the girl developed a liking for observing insects.

Years later, the description of silkworms would open Maria Sybilla’s book on caterpillars, and the title page would be dedicated to them as well: “Sitting on a mulberry tree leaf is a big silkworm. It is about to turn into a cocoon. The worm is white and half-transparent. From its mouth, silk threads are stretching. These will be used to build a house. Then a cocoon is formed, and then a moth.” Basing on her own experience, the explorer concludes: “The moths lay round yellow eggs and die. From the eggs put in a warm place, larvae hatch. They shouldn’t be given wet leaves, or they will fall ill and die. Also, they can be sick because of bad weather, so they should be covered.”

“…heroic love for insects”

An important event for Maria Sybilla as a scientist was, undoubtedly, her trip to Surinam. The three-month sea voyage on a trade sailboat undertaken by a woman with a young daughter is amazing and admirable: any day, the boat could have been wrecked by a storm or the travelers could have perished at the hand of a pirate.

The French scientist R. Reaumur remarked, “Mrs. Merian was called to Surinam by her truly heroic love for insects; it was quite an event: a woman crossed the seas to draw American insects after she had depicted a great many of the European ones; she returned from there with tables showing an impressive number of splendid species of butterflies and caterpillars, which were superbly engraved”But such was her drive for knowledge. In her book Metamorphoses of Surinam Insects (Metamorphosis insectorum surinamensium, Amstelodami, 1705), Maria Sybilla writes about the insects as follows, “Neither their origin, nor development, that is how larvae turn into cocoons, or any other transformations were known. This urged me to take a long journey across Surinam in America, a hot and moist land, from where most insects <...> that people know originate.”

The result of the two-year stay in the exotic land were hundreds of sketches, drawings (“I make true copies of everything I have found and caught…on parchment”2), notes with observations, and numerous boxes with collections: 20 boxes with butterflies, bugs, hummingbirds, and glowworms; “1 crocodile, 2 big snakes and 19 small snakes, 11 iguanas, 1 gecko, and 1 small turoise.”3

On her return to Amsterdam in 1705, Maria Sybilla issued a book devoted to Surinam insects. It may be appropriate to note that most of her books Merian published at her own cost and expense.

Amsterdam – St Petersburg

The importance of Maria Sybilla’s studies for entomology and botany has been discussed in the literature extensively and in detail.4 Art experts analyze the specific features of her artistic skills.

As a rule, the artist created her works on thin vellum charta non nata (“unborn skin”). She applied the priming white coat to produce a tender and smooth surface. Merian would ordinarily use watercolors and gouache. It is amazing that in three hundred years the colors look so fresh as though the artist has just put aside her brush...

The Petersburg collection of Maria Sybilla’s watercolors is one of the world’s largest. Besides, a considerable part of the life of her daughter Dorothea Maria Gzell* was connected with Petersburg.

Merian’s watercolors kept at the St. Petersburg Branch of the RAS Archive got there from different sources.5 In the first place, these are the watercolors acquired by Peter the Great and his Surgeon in Ordinary and collection keeper R. K. Areskin. There is a legend that Peter I, who was in Amsterdam in 1717, came to Merian’s house on the day she died of paralysis.

Concerning the purchase of watercolors, the historian of Peter the First, I. I. Golikov wrote, “At that time [in 1717] the monarch purchased, for a substantial sum of money, the paintings of honored Marianna, which consisted of two thick vellum books the size of the Alexandria sheet; over 200 paintings taken from the life with inimitable art, of flowers, fruits, shells, butterflies and other insects, as well as Surinam works.<…> The sovereign honored these paintings highly, and they were always in his study.”6 After the tsar’s death, the paintings, together with his library, were passed over to the Academy of Sciences.7

Areskin purchased the album Studienbuch with paintings of insects. Glued on the odd folios of the album sheets were paintings made on vellum or paper and put into blue paper frames (285 works all in all). The even folios had Merian’s notes, which, as deduced from the handwriting analysis, had been made during 30 years.8 Areskin bought some other of Maria Sybilla’s watercolors too.

Merian’s watercolors found their way to the Academy of Sciences in the 19th century too. For example, on June 15, 1864 the famous Academician K. M. Baer reported to the Department of Physics and Mathematics that the doctor of medicine, member of the Council of Medicine with the Ministry of Internal Affairs Е. J. Ruach “has left to the Academy of Sciences a collection of drawings showing natural science objects. Some of them belong to the famous Sybilla Merian.”9 In the late 19th century, Academician M. S. Voronin presented to the Botanical Institute 18 drawings he had brought from his trip to Germany. Further migration of Merian’s drawings about the institutes of the Academy of Sciences in Petersburg is related in detail in a few papers.10 Note that today 184 watercolors are kept at the St. Petersburg Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences Archive (SPB RASA), where they got in 1939 from the Zoological Museum, USSR Academy of Sciences. The RAS Library has the Studienbuch album, and another 18 watercolors from the Voronin collection are at the library of the Botanical Institute, RASIn 1733, Dorothea Maria, who went to Holland “for her own <…> needs,” brought some of her mother’s watercolors, 34 of which were purchased by the Academy of Sciences. By 1741, the Petersburg Museum had no fewer than eight albums containing the artist’s original paintings.

Tsar and collector

The interest Peter I took in Maria Sybilla was not accidental. By 1717, when Peter I and Areskin purchased her works, she was famous both as a painter and as a scientist. She was known as the author of several books and explorer of insects, who had collected in Surinam a high number of naturalia to be sold to collectors.

She belonged to the circle of people Peter I got acquainted with during his first trip to Holland. Merian wrote that “the most curious things she saw in Holland were various insects brought from both Indies, especially after she obtained permission to examine the study of famous Nicolaes Witsen, the mayor of Amsterdam and administrator of the Dutch East India Company, and the collection of Jonas Witsen, secretary of the municipal administration. I saw the interesting study of Frederik Ruysch, a famed doctor of medicine and professor of anatomy and botany; and finally, the collections of Livinus Vincent and of many others, where I found countless insects…”

Merian’s daughters inherited their mother’s talent. Regrettably, it is not known yet whether the drawings of Merian’s youngest daughter, Dorothea Maria Gzell, have survived and, if yes, where they are. It is known from the archive documents that she drew rare birds and plants; on her orders, they used to make fashion parchment paper in Petersburg…According to K. R. Berk, the drawings of Maria Sybilla’s older daughter, Johanna Helena, were in Petersburg as well. Informing about Dorothea that she “helped her mother to work on the Surinam insects by drawing and coloring prints,” Berk wrote, “Her sister, who subsequently traveled to Surinam, collected rare cultural plants. Having made sketches of them, she passed them on to Madam Gzell for completion, which was done with extraordinary elegance. I saw these drawings together with enclosed descriptions in the Dutch language; she wishes to sell them if there is a purchaser who will offer a worthy price”11

This note is dated by 1705 – by that time Witsen was not a mere acquaintance of the Russian Tsar, but his counselor and assistant. Peter I saw Ruysch’s famous anatomical “thesauruses” as far back as in 1697; and by 1717 he purchased them for the Kunstkamera at 30,000 Dutch guilders. In the same year 1697, Peter got acquainted with the celebrated collection of Livinus Vincent.

Also, Peter heard about Merian’s books from another collector, the Amsterdam pharmacist Albertus Seba, whose natural science and art collection was acquired by Peter I for the Kunstkamera. Praising his collection, Seba wrote to the Russian Tsar on October 4, 1715, that together with the “curiosities” he would send “magnificent books dwelling on all these objects <…> by Rumphius about shells and by Merian about various creeping and other things.”12

Peter, who became a passionate collector, knew the insect “metamorphoses” Maria Sybilla painted and wrote about. For instance, in Vincent’s collections butterflies were presented by stages of development: from larva and cocoon to a butterfly. On return from his first trip, Peter not only corresponded with his new acquaintances but, as a true collector, exchanged with them naturalia from Russia. We know from Ruysch’s letter to the Russian tsar dated July 16, 1701, that Peter I sent to Witsen alcohol preparations of lizards and worms with the provision that he would share them with Ruysch.

Positively, Peter had heard about the works of Maria Sybilla Merian. Interested as he was in the artistic merit of her watercolors, he was undoubtedly more attracted by their educational value. It was not for nothing that Areskin purchased the manuscript of Studienbuch, which contained the notes of Merian’s observations made over 30 years. Also, it is not by chance that the watercolors kept at the SB RASA are not decorative depictions of plants, which Maria Sybilla painted many, but illustrations to Metamorphoses and Rumphius.

Later, Merian’s watercolors were considered and displayed as particularly valuably exhibits of Kunstkamera. The well-known French traveler Henri de la Montrais, who visited Petersburg in 1726, recollected having seen Metamorphoses in the Academy’s library, “This work deals with various changes or transformations of insects, plants, flowers, etc. Mrs. Merian superbly painted a lot of various plants, especially flowers, and these were the drawings he [J. D. Schumacher, the librarian] showed me.”13

Merian’s watercolors were more than “curiosities”: Petersburg scientists turned to them and to her books when they described the collections of their unique museum. When describing the naturalia, the authors of the catalogue Musei imperialis Petropolitani… referred, as a rule, to the scientific publications of the time, and when dealing with the entomological collection, they often mentioned Merian’s Metamorphoses.14

The hand of an artist, the eye of a scientist

The librarian of the Imperial Academy of Sciences J. G. Bakmeister wrote in his book about the library and Kunstkamera that “Worthy of particular attention of connoisseurs are the marvelous miniature paintings of flowers, worms, and other insects made on special vellum sheets by the glorious Maria Sybilla Mariana with an extraordinary taste and consideration.”

Indeed, till this day everybody who sees these watercolors cannot help admiring their beauty. Do we ponder what stands behind these “tender drawings”? At first, when depicting flowers, Maria Sybilla only tried to “enliven” them, showing caterpillars on their leaves, “since I always did best to decorate my flower paintings with caterpillars, summer birds [butterflies] and other suchlike animals, in the same way landscape painters do with their works to brighten up one thing with the other, I often had to put a great effort in catching them until, finally, through silkworms came to consider caterpillar transformation and began thinking about whether the same transformation may take place there as well.”15

From these thoughts Maria Sybilla proceeded to observations. Here is one of them, “On April 10, 1684, I received a grey thrush. Something moved inside its body, though it was dead. I wanted to find out the reason and dissected its belly. It was full of white worms. I put the bird into a box. The worms ate all the bird and turned into eggs. From the eggs, only one fly appeared, the others got dry.”

Observing insect transformations, Maria Sybilla put down what they ate and how they reacted to stimulations. This note is about the larvae of the purple Tiger moth she found among yellow buttercups, which the larvae devoured with great pleasure, “If there are no these flowers, they can also eat sour sorrel, withered nettle, dandelions and currents. <…> When something touches them, they curl themselves into a ball.” And here is a description of the tussock butterfly transformation, “At the beginning of May this larva undergoes transformation. It takes its own hairs, then takes some chips (if there are any), crunches them into fine bits, and weaves an oblong egg out of them. Then it turns into something resembling a date-stone [cocoon]. At the end of May, this yellowish-brownish moth comes out …”

At times, the rich world of butterflies made Maria Sybilla portray their beauty not only in paints but in words as well, as she exclaimed, “I would have never believed that such an ugly creature as a black caterpillar could produce such a lovely butterfly.” And another observation, “A splendid, silvery butterfly appeared. <…> In some places, the green, blue and pearl showed under the upper color. In a word, so beautiful that neither my pen nor my brush can do it credit. Each wing has three round orange spots with a black edge; and around this black circle there goes a green one. The brims of the wings are orange, with black and white stripes.”

Maria Sybilla wrote about the aim of her scientific and artistic work that she would like to “give pleasure to connoisseurs and those who study the nature of insects and plants, and to live up to their expectations; I will be happy if I have succeeded in it.”

Almost three hundred years passed since the artist created her amazing watercolors, which are full of life. Her expectations have come true: even today, in the age of photography and computer technologies, her wonderful and true to life works not only give esthetic pleasure but set an example of popular science illustrations.

References

1 Lukina Т. А. Maria-Sybilla Merian, 1647—1717. Moscow: Nauka, 1980.

2 From the letter of M. S. Merian to the Nurnberg doctor J. G. Folkamer dated October 8, 1702. Cit. from Ullmann Ch. Maria Sybilla Merian – her time, life, and work//Merian M. S. Leningrader Aquarelle. Leipzig, 1974. S. 57.

3 Ibid. S. 51.

4 See, for example, Beer V.-D. Maria Sybilla Merian and natural sciences // Merian M. S. Leningrader Aquarelle. Leipzig, 1974. S. 77—113. The author comments that in Maria Sybilla’s watercolors scientific authenticity often submits to the general artistic impression, when “for esthetic reasons larvae are sometimes introduced, which have nothing in common with the content of the picture.” (P. 93—95).

5 See Lukin B. V. To the history of the Leningrad collection of Maria Sybilla Merian’s watercolors // Merian M. S. Leningrader Aquarelle. Leipzig, 1974; Lebedeva I.N. Artistic and scientific heritage of Maria Sybilla Merian in St Petersburg // Peter I and Holland. St Petersburg, 1997. P. 318—334.

6 Golikov I. Acts of Peter the Great. 2nd edition. Vol. IV. P. 200.

7 Historical essay and overview of the archives of the Manuscript Department, Library of the Academy of Sciences. Moscow; Leningrad, 1956. Iss.1. P. 368.

8 See the description of this manuscript: Latin alphabet manuscripts of the 16th-17th cc. Compiled by I. N. Lebedeva. Leningrad, 1979. P. 136—139.

9 SPB RASA. Archive 1, Inventory 2-1864, File 20, § 134, Sheet 1.

10 See the articles by B. V. Lukin and I. N. Lebedeva above.

11 Berk К. R. Travelling notes about Russia // Bespiatyh Yu. N. The Peterburg of Anna Ioannovna as described by foreigners. St Petersburg, 1997. P. 196—197.

12 Pekarsky. P. 36.

13 De la Motrais H. From “the journey…”// Bespiatyh Yu. N. The Peterburg of Peter I as described by foreigners. Leningrad, 1991. P. 223—224.

14 See, e. g., Musei imperialis Petropolitani... Vol. I. Pars Prima. P. 663. N 4, 5, 7; P. 664. N 8, 16, P. 668. N 70 etc

15 Ullmann Ch. Maria Sybilla Merian – her time, life, and work // Merian M. S. Leningrader Aquarelle. Leipzig, 1974. S. 39.

* Dorothea Maria and her husband Georg Gzell were engaged to work in Russia in 1717. Apart from painting, they mounted Kunstkamera exhibitions, and subsequently taught drawing and painting at the newly set up Academy of Sciences