Walk through the Paper Museum of the Imperial St. Petersburg Museum

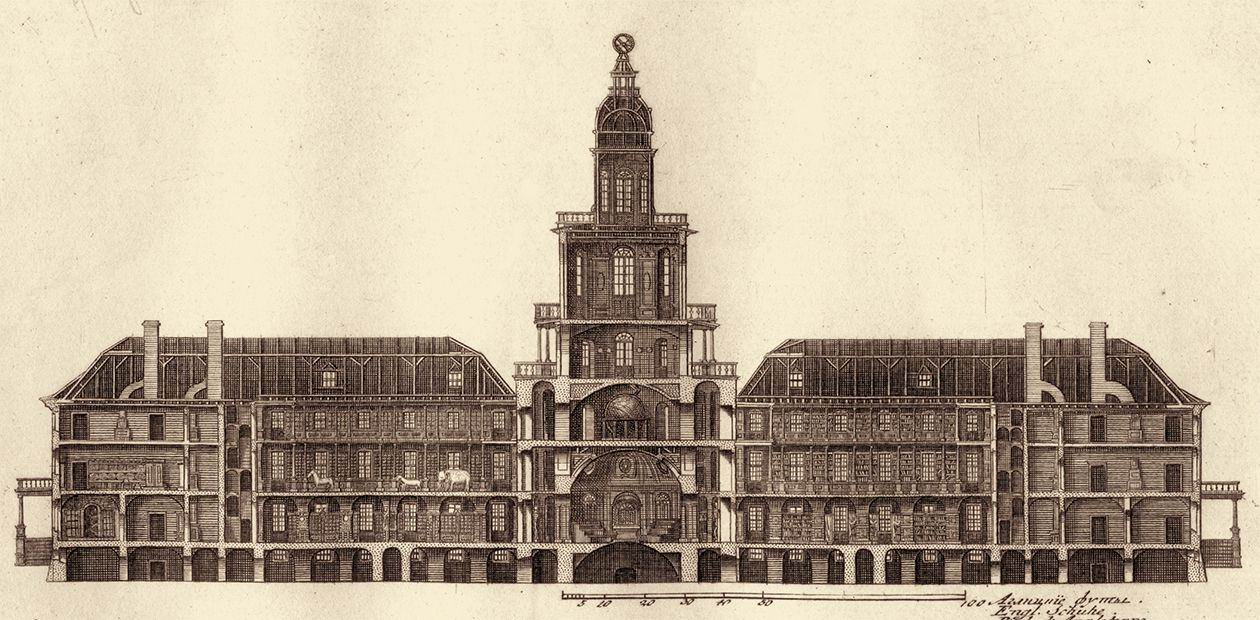

The famous building on Vasilievsky Island in St. Petersburg, which has become the emblem of the Russian Academy of Sciences, is known as the Kunstkamera. The Kunstkamera museum in its modern form is basically associated with its outstanding anatomical collection purchased by Tsar Peter the Great from the Dutch anatomist Frederick Ruysch. Human curiosity has not changed much since the 18th century, and “the multitude of various organs and monsters, both instructive and curious” 1 continues to attract most of the visitors.

The general public, however, tends to have a one-sided idea of this museum, which dates back to the first half of the 18th century. In fact, it was a magnificent museum with universal collections — a kind of precursor to the encyclopedic trends characteristic of the second half of the 18th century. The museum was famous for its collections of birds, snakes, insects, minerals and coins, as well as for its herbariums and collections of ethnographic and archaeological objects. Being part of the Academy of Sciences, the museum served as a scientific laboratory, and it is this function of the Kunstkamera that was of primary importance in the 18th century.

The museum’s archives expanded owing to academic expeditions; the collections acquired, apart from being decorative, were of great scholarly value. For instance, the collection purchased by Tsar Peter I from the Dutch anatomist Frederick Ruysch was largely composed of items demonstrating human internal organs and prenatal development. The Kunstkamera’s first catalogue, published in Latin, disproves the popular view that Ruysch’s collection was an assemblage of the so-called “monsters,” mistakes made by nature, or all kinds of abnormalities. On the basis of this misconception, Peter’s interest in anatomy was attributed not to the thirst for knowledge — a quality inherent in any intelligent human being — but to his morbid attraction to monstrosities.

Anatomical exhibits were grouped into cabinets, each housing preparations of a certain human organ — skin, muscles, brain, etc. — according to the systematization of the day. The people who visited the Kunstkamera in the first decades of its existence were especially allured by the preparations showing development of the human fetus, “all parts and stages of its development and the child’s position in the uterus at the age of 15 days to 9 months” 2. This interest in the museum’s anatomical collection shows that our ideas about the 18th-century Museum of the Academy of Sciences are not always correct.

It is our good luck that there are sources allowing us not only to expand our knowledge about the museum but to see its exhibits thanks to the collection of watercolors which has become known as the “Paper Museum.”

The Paper Museum is watercolors produced by artists of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences; they depict the objects that had been in the Kunstkamera’s collection by the 1720s and also those which joined it later — they were brought from academic expeditions or purchased. As early as in the 1730s—1740s, these watercolors were kept in folio in large boxes imitating book binding. The second volume of the museum’s catalogue, printed in Latin by the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences in 1741 3, lists 58 boxes with watercolors but it gives no indication of how many watercolors were contained in each box.

The hand-written original of this part of the catalogue 4 kept at the St. Petersburg branch of the Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences gives evidence about the number of watercolors kept in 27 (out of 58) boxes at the end of the 1730s. 5 However, even these incomplete data testify to the scope of drawing activities undertaken by the Academy of Sciences. The corpus of the drawings listed includes 293 anatomical sheets (excluding the drawings of “monsters”); 1137 botanical drawings; 76 drafts of scientific instruments; 141 watercolors depicting clothes worn by various peoples, primarily those inhabiting Siberia and the Volga region; and 356 drawings of the Chinese collection. We should emphasize again that these data are far from being complete. For instance, the hand-written catalogue makes no mention of numismatic drawings, which number about a thousand sheets.

Large collections of drawings depicting Kunstkamera’s objects are kept in three institutions in St. Petersburg: the St. Petersburg branch of the Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Hermitage and, the Russian Museum. In 2003 and 2004, a team from researchers of St. Petersburg and Amsterdam published a catalogue of the drawings’ descriptions in Russian, and in 2005 the catalogue was published in English 6. It is evident how important these watercolors are for us today, so let us use the unique opportunity to see the objects of this academic museum while taking a walk about the Paper Museum.

…DEPICTING THE OBJECTS OF THE SAID KUNSTKAMERA IN WATER COLORS, ARRANGED ACCORDING TO THE CLASSES THEY BELONG TO

On a December day in 1723, Maria Dorothea Gsell, who together with her husband, artist Georg Gsell, had come to St. Petersburg in 1717 on the invitation of Peter I, reported to the cabinet of His Imperial Majesty: “His Imperial Majesty has most graciously ordered, through the Court Physician Lavrenty Lanventyevich Blumentrost, that I become attached to the Kunstkamera and depict the objects of the said Kunstkamera in water colors, arranged according to the classes they belong to.” 7 (italicized by N. K.) This short document indicates that it was Peter the Great’s idea to produce these drawings; that this task was entrusted to the daughter of the renowned Maria Sibylla Merian, 8 M. D. Gsell; that they were to be on parchment and grouped in classes.

On March 4, 1724, J. D. Schumacher 9 filed a request with the Admiralty College for “the production of parchment at Admiralty’s parchment mills for depicting curiosities,” 10 and on March 17, he received 22 calf hides for producing this expensive material. 11 Regretfully, despite these documented data, we do not have any depiction of the Kunstkamera’s objects on parchment: all the known drawings of the Paper Museum are on Dutch paper. No drawings made by M. D. Gsell have been traced either.

Almost all sheets with drawings bear various kinds of marks. First, we can see reference to pages of the printed catalogue Musei Imperialis Petropolitani, mentioned above. The catalogue lists all the objects by thematic collections; and inside the collections, by the cabinets where the objects were held. Sheets depicting objects bear ink inscriptions indicating pages of the catalogue and number of the cabinet where the object was kept. Most drawings have this kind of “address,” which enabled the authors of the catalogue The Paper Museum of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg to place the descriptions of watercolors in the cabinets where the objects depicted had been kept.

Some drawings were signed by artists but most, regrettably, bear no names of their authors. It should be noted that the works produced by the artists of the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences have been studied poorly. Let us give a few names. After M. D. Gsell, Kunstkamera’s objects were painted by A. Grekov (1711—1791), who was the curator of the anatomical collection and a watercolor painter, and by J. Ch. Berckhan (1709—1751), better known as a member of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, who worked at the Kunstkamera in 1747—1751 drawing ethnographic and zoological collections of the museum. In 1749—1754, his fellow member of the expedition J. W. Lursenius (1704—1771) served at the Kunstkamera as a master of “drawing plants and naturalia.” Also, the museum’s objects were drawn by the subsequently famous Russian engravers I. A. Sokolov (1717—1757) and M. I. Makhaev (1717—1770), and by the little known but talented artist Ya. Nechaev (?—1771), who studied under A. Grekov.

If we consider the drawings preserved to this day from the point of view of their artistic value, they certainly differ a lot. Quite often, the Kunstkamera’s objects were depicted by the students of the art chamber or of the engraving chamber of the Academy of Sciences at their drawing lessons.

The manner of depicting museum objects was also different. It is worth noting that the depictions had to be life-size, or give an indication of the scale or of the object’s size. Museum objects were depicted in the way they were exhibited. Alcohol preparations were drawn together with the jar housing them. Some of the jars had lids in the old kunstkamera tradition. Such elaborately composed lids were characteristic of F. Ruysch’s collection as well as of another collection purchased by Peter I in Amsterdam — that of Albert Seba.

Articles of clothing were shown as hanging in the cabinets because the 18th-century Kunstkamera had no dolls. Some stuffed specimens of birds were hung on a nail or exhibited together with their nests – and were shown in the drawings in this way. Some of the drawings present a plot: a rat with a bread crust, two snakes ready to attack…

…A CRICKET OF EAST INDIA

Though we do not possess all the drawings of the Kunstkamera’s objects, the drawings which survived suggest that this academic museum was of encyclopedic nature. All the exhibits were divided into two big groups, naturalia and artificialia. The classification within the groups reflected the state of sciences at that time. Natural knowledge had a classification of its own, on which St. Petersburg professors relied. By contrast, humanities such as ethnography and archaeology were in the process of formation, which was reflected in the collections of the academic museum.

The St. Petersburg branch of the Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences contains watercolors showing anatomical preparations of “monsters” and of the so-called “living monster,” the Kunstkamera’s richest zoological collections including the drawings of quadrupeds, birds, fishes, amphibians, lizards and insects. The drawings preserved to this day testify to the great variety of the museum’s zoological collections. Let us remind you that their formation goes back to Peter I, who purchased the collections of F. Ruysch and A. Seba, which comprised stuffed specimens and alcohol preparations of exotic animals from Dutch colonies. We cannot resist the temptation to quote Ruysch’s letter to Tsar Peter I, dated July 16, 1701, which shows how enthusiastic they both were about collecting naturalia. In his letter, Ruysch thanked Peter I for the alcohol preparations of lizards and worms Peter had sent him. The Amsterdam anatomist returned his thanks by sending to Russia “1) a highly peculiar lizard with sharp scales; 2) a small ligvan with green belly from West Indies; 3) a fish from Caracuas Island; 4) a snake with two heads from the same location; 5) a cricket of East India,” etc., — eleven insects, snakes and lizards all in all. The anatomist reminded the Tsar that when the latter was in Amsterdam he made a note in his book about Ruysch’s request to send him two dressed human skins. The professor from Amsterdam not only asked to send him “worms with yellow spots…, various beetles, …big flies and gad-flies,” etc., but also instructed the Tsar how this “treasure” was to be preserved: “If you happen to collect all these creatures in a box, you should feed them with the fresh leaves on which they live. You will then be able to see how they are changing and, in a few days, turning into butterflies. This butterfly shall be pierced with a pin and fixed in the hanging position in the box, and the box shall be sealed so that no beast can spoil it…Other worms can be dealt with in a similar way. We have no doubt that in Moscow extraordinary butterflies and other beasts are abundant…” 12

NATURALIA AND ARTIFICIALIA

In the later years, the Academy of Sciences focused attention on adding to its collection species of animals, birds and fishes inhabiting the territory of the Russian Empire, and primarily that of Siberia. The drawings show exotic snakes, crocodiles, lizards, a chat (Oenanthe sp.) and… a fragment of a mammoth’s tusk. Regrettably, no drawings of butterflies have survived or have been found yet — this collection must have been truly amazing, judging by its description in the catalogue.

The Kunstkamera’s herbarium was just as rich. Peter I purchased a collection of dried plants, again from Ruysch; the herbariums had been prepared by academic professors. Apart from the herbariums, the botanical collection can be said to include drawings of plants made in the field or later, in St. Petersburg, based on drafts and sketches. A separate place was reserved for watercolors published in Centuria by the St. Petersburg professor J. Buxbaum (1693—1730), the first work printed by the Academy of Sciences — Plantarum minus cognitarum complectens plantas circa Bysantium et in Oriente observatas...Centuria 1-5, Petropoli, 1728—1740. 13

In contrast to the naturalia, the artificialia were exhibits made by man, not by nature. Here belonged, in the first place, archaeological and ethnographic collections. A particular place among the latter was occupied by the collection of Chinese pieces and by articles of clothing, religion and household amenities of Siberian peoples. The preserved drawings of these collections are unique as they are the earliest depictions of this kind of collections. The drawings are also important because the greater part of the exhibits depicted perished in the fire which devastated the museum in December 1747.

The Chinese collection amounted to almost one third of the art objects listed among Kunstkamera’s original acquisitions. The museum’s catalogue contained 150 descriptions of exhibits regarded as Chinese; a lot of descriptions summed up a group of objects. For example, «Figurae Chinenses in gypfo cauato» are described under numbers 159—175, and «Figurae Chinenses in gypfo anaglypho», under numbers 176—189. Chinese items came from different sources: some were individual gifts whilst others made part of large collections such as those of the already mentioned A. Seba or Y. Bruce, a high-ranking army officer. In the Kunstkamera building, Chinese objects were kept in the second-story gallery, together with other artificialia: objects made of stone, wood and bone on the right hand; clothes and religious attributes, which would now be jointly referred to as the ethnographic collection, on the left hand.

Drawings of Chinese objects played an important role in the restoration of collections destroyed by the devastating fire of 1747. For instance, in 1753 copies of several drawings were given to the physician F. Elachich, who was going to China to purchase replacements of the missing objects shown. The St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences has the Catalogue given to doctor Elachich going to Peking with a convoy with the purpose of purchasing similar objects. 14 These drawings, executed in a hasty manner but giving a precise idea of the object, its size and the material it was made of (silk, china, stone, etc.), are a valuable (I would say, invaluable — N.K.) document which can be used to restore the Kunstkamera’s Chinese collections.

Ethnographic collections of the artifacts representing Siberian cultures were formed as a result of academic expeditions. The first important acquisition was connected with D. Messerschmidt’s return from his expedition to Siberia. Regrettably, neither the drawings nor the printed catalogue contains any indication of the provenance of the exhibits. We can only suppose that the drawings of the 1730s show items brought by Messerschmidt or by members of the Second Kamchatka Expedition. Marks made on the drawings that attribute the objects depicted to a certain people are not always correct, which suggests that the attribution was made later, in the museum. Drawings that have survived to this day and the evidence of contemporaries testify that the Kunstkamera had one of the richest ethnographic collections in Europe. K. P. Berch, a learned Swede studying antiquities, who lived in St. Petersburg from the end of 1735 to May 1736, wrote: “I was present when some of the packages were opened and I saw… various figures, copper and iron, and instruments found in mounds; and various gods that the pagans living in those areas of the country continue to worship. Some gods were faces made of wood or copper; others were made of black sheep hides drawn over thick felt, with blue pearls instead of eyes and fur shorn on the heads to make them look somewhat like faces. The most beautiful were a few collections of figures from the Chinese border, carved out of fine transparent stone. Strangest among the clothes were mantles of some sorcerers and sorceresses made from undressed hides, with numerous belts attached to the back and to the sleeves (almost like a lackey’s laces) and pieces of iron and brass tied to them; the latter made a terrible noise. There were similar hanging belts on headgear… and tambourines.” 15

Drawings showing exhibits of the Kunstkamera’s archaeological collection deserve special attention. Some sheets contain later inscriptions indicating that the objects depicted belonged to D. G. Messerschmidt’s collection and that they resembled the engravings published by the Benedictine monk B. Montfaucon.16

The Paper Museum demonstrates many other exhibits of the St. Petersburg museum. Thus, the Kunstkamera had a specific collection of instruments and scientific apparatuses which were drawn as museum objects; also, there was a variety of memorabilia related to some historical figures or events. These items, however, mainly referred to the time of Peter the Great.

Many of the drawings haven’t survived to this day or haven’t yet been located. It is known that the Paper Museum watercolors kept at the State Russian Museum and some zoological drawings were purchased from an individual. After the catalogue The Paper Museum of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg was published, one of the drawings was traced to Peter the Great’s Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (the Kunstkamera) of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and a few watercolors were discovered at the Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences. We cherish a hope to find a large corpus of drawings depicting gems and butterflies. The search is going on, and it means that our “walk” about the St. Petersburg museum of the first half of the 18th century may continue.

1, 2 Aubrey de La Montraye, Voyages en divers provinces in: Y. N. Bespiatych, Petersburg of Peter I as described by foreigners, Leningrad 1991, p. 225.

3 Musei Imperialis Petropolitani, typis Academiae Scientiarum Petropolitanae, 1741—1745. Vol. 1–2.

4 St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Collection III, inventory 1, no. 387, leaf 112, side 114.

5 This document was published in the second volume of Paper Museum of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, 1725—1760, St. Petersburg, 2004, Vol. 2, pp. 160–161. The two volumes of this book (the first volume was published in 2003) contain descriptions of the watercolors preserved to this day in St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences., State Hermitage and State Russian Museum.

6 Paper Museum of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, 1725—1760, Vol. 1, St. Petersburg 2003. Vol. 2, St. Petersburg 2004.

7 Materials for the history of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, St Petersburg 1888, Vol. 1 (1716—1730). p. 12.

8 Maria Sybilla Merian (1647—1717), artist and naturalist.

9 Johann Daniel Schumacher (1690—1761), librarian, Office Counsel of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences.

10 Materials for the history of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, St Petersburg 1888, Vol. 1 (1716—1730). p. 34..

11 St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Collection III, inventory 1, no. 1, leaves 84—85.

12 Quoted from P. Pekarsky, Science and Literature in Russia at the time of Peter the Great, St. Petersburg 1862, vol. 1, pp. 520—521.

13 A. K. Sytin Botany and J. Ch. Buxbaum in: Paper Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg.

14 St. Petersburg Branch of the Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Collection III, inventory 1, no. 808a, leaves 1—144.

15 Y. N. Bespiatych, St Petersburg at the time of Anna Ioannovna as Described by Foreigners, St. Petersburg 1997, p. 184.

16 A. A. Formozov, From the History of the Kunstkamera in: Questions of History, 1968, no. 5, pp. 214–216.