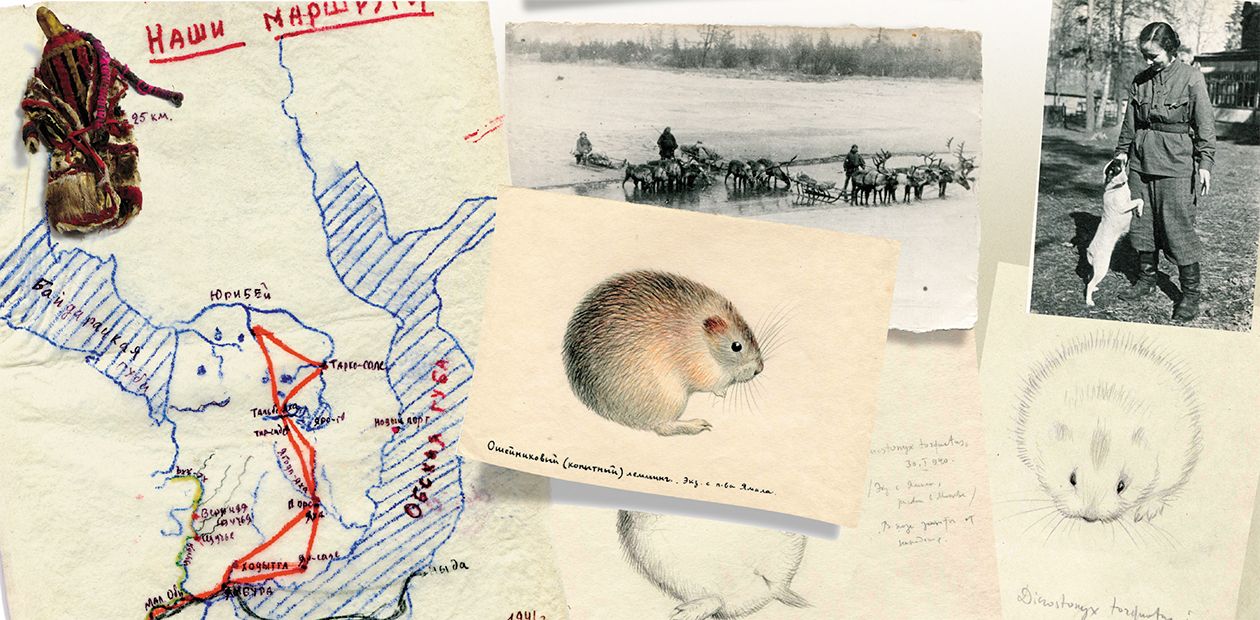

"On a Bright and Sunny Night…" On the Life of Two Women Zoologists from Moscow in the Yamal Tundra during the Second World War

The memoirs by Varvara I. Osmolovskaya, excerpts from which are in front of you, were written, so to say, for home use. One of the subheadings of the manuscript was "To my children and grandchildren." The story is as follows. In 1941, having graduated from Moscow University, two friends, Varia Osmolovskaya and Tania Dunaeva, went on an expedition to Yamal for their first summer at the postgraduate school. They left in May and found out that World War II had broken out when they were in the tundra, on the River Shchuchya. They decided to keep to their plans. In mid-August, in the upper reaches of a tributary of the River Shchuchya, they encountered a topographer making his way across Yamal to Salekhard. It was he who told them that the Germans were near Smolensk and that Moscow was being bombed… It became clear that going back home that year was hardly possible. In this way, the expedition planned for one season lasted two winters and three summers. Both for Varia and for Tania these were the years of dedicated work and fascinating experience of living among the Nenets. In 1942, they moved with reindeer herds for five months

The memoirs by Varvara I. Osmolovskaya, excerpts from which are in front of you, were written, so to say, for home use. One of the subheadings of the manuscript was “To my children and grandchildren.”

The story is as follows. In 1941, having graduated from Moscow University, two friends, Varia Osmolovskaya and Tania Dunaeva, went on an expedition to Yamal for their first summer at the postgraduate school. They left in May and found out that World War II had broken out when they were in the tundra, on the River Shchuchya. They decided to keep to their plans. In mid-August, in the upper reaches of a tributary of the River Shchuchya, they encountered a topographer making his way across Yamal, from Baydaratskaya Bay to Salekhard. It was he who told them that the Germans were near Smolensk and that Moscow was being bombed… It became clear that going back home that year was hardly possible. In this way, the expedition planned for one season lasted two winters and three summers. Both for Varia and for Tania these were the years of dedicated work and fascinating experience of living among the Nenets (in 1942, they moved with reindeer herds for five months).

My sister Liza and I asked our mother many times to write memoirs about “the Nenets,” stories of whom we had liked since childhood. But the mother declined to do it: inexplicably, she did not think much of her writing talent. One day in the summer of 1986, a new book by Yuri Rytkheu came to her hand. It excited and touched her; having read it, the mother took pen in hand and, in a few months, her “documentary story” was completed.

Mother tells about the Nenets with humor, and they treated her in the same way: made jokes and gave funny nicknames. She writes that she enjoyed their company more than that of the local Russians. I think the Nenets also understood that the girls who came to them were not quite ordinary. Did they find them interesting? Probably, yes, but in the first place they took good care of them. In the only photograph preserved of summer 1942, Varia, who has come to visit Tania’s raw-hide tent is wrapped in men’s sook (winter upper garment made from fur). “Lose a Russian girl – may go to court,” Pari once jested.

Thanks to this remarkable experiment the Nenets culture became part of our lives – my sister and I grew up on Yamal stories. Whether this cross-ethnic interaction left any traces with the Nenets, what the lives of “Noliku Tania” and “Noliku Varia” (little girls called by the parents after the two Moscow post-graduates) were and whether anybody has narrated, at least once, Pushkin’s “Goldfish” told in the Nenets tent by my mother – is not known.

After the retirement, Mother went to the North several times. In 1977, she visited, together with Tania, Lappish National Park on the Hibiny; in 1986, went to Chukotka as a member of an expedition of a former student of hers. Every time it was called “Saying farewell to the tundra.” I tried many times to talk Mother into going to Yamal, but she always refused, “Everything’s different there now and there are no people I knew,” and she never went.

Once after my mother’s death in 1994, Tatiana Dunaeva said, “Varia wrote very well about the tundra, I could not have done it that well. Varia was loved by the Nenets, and I was respected and… and a little bit feared.” Tatiana would reduce disjunctions of reindeer and give instructions on what should be done after an attack by a rabid wolf; once, she must have saved the life of a man who had carelessly skinned a reindeer that had anthrax by disinfecting a wound on his hand. “Tania, pydar lekar’ savorka!” (“Tania, you’re a good doctor!” the Nenets used to say. Now she is 94, keeps to her bed. The last time I saw her she proposed me a Nenets riddle she had kept in memory for 68 years: “Tuko amge? Side puhoche yadempei peuda?” (“What’s this? Two women quarrel all the time.)” The answer is two sticks supporting the tent hide: they are crossed all day, and the wind rubs them against each other. Also, she keeps repeating Lousoma’s words, “Man Varia hupta, pydyr optike Varia (My Varia is far away, you are the same as Varia).” All geographical names and Nenets words in the memoirs are given in the transcription noted by the author.

By reindeer up the Poluy River

Right after the semester was over, they offered me a trip to the upper reaches of the Poluy River in the capacity of instructor. It turned out that Soyuzpushnina (in the USSR, the foreign economic body that monopolized fur export) had budgeted some “technical propaganda” expenses, and the plan had to be fulfilled. Nobody was interested in what I was going to do there without knowing the language, what kind of training I was going to get and whether it would be of any use to me. What mattered was executing the plan and using the money allotted. I happily accepted. ‹…› I left on December 19, at 6 p.m. For the Nenets, it does not matter whether it is day or night – they can travel any time. We were going through a totally white mist. ‹…› The reindeer were running on top of hard, pressed snow; the driver was sitting calmly in front, on the left side of the sledge, humming a melancholic song without words or tune. In his left hand was a long pole with a round head, or tur, in his right hand was the trace of the front bull’s bridle. I wasn’t able to see if he was driving the reindeer; they seemed to be running on their own. I was sitting behind the Nenets, on the right side of the sledge, my feet on the sledge runners, and listening to the driver singing, trying to make out something in this unending mist but could see nothing. We seemed to be going into some white non-existence and our trip appeared to have no end.

All of a sudden, dogs barked and triangular silhouettes of three tents came in sight – we reached our destination. Then and much later it often occurred to me that before studying migrations of birds and their amazing ability to orient themselves, we should figure out how the Nenets manage to find their way in the tundra.

All the tents’ residents came out to greet us, and among them, like robust ceps, small kids in well-fitted reindeer parkas sewn from the young reindeer hide. Greetings, loud incomprehensible conversation. Everybody went inside a tent. There was a fire blazing in the middle, a big kettle and a teapot hanging over it. The smoke from the fire went up and out through the hole between the poles. Outside, as I found out later, the hole was covered with a piece of hide, which was moved by the hanging down ropes, and so it could be positioned, depending on the wind direction, to provide for the draft. There were two broad planks on the sides of the fire, then went wicker mats covered with reindeer skin. Everybody took their places. I was seated in front, as a guest; my driver next to me; then came the host and the hostess; then the children; and right at the entrance were dogs. The host was wearing his hair in two small plaits, and this told me that I was in a Khanty tent.

‹…› When we left the tent, it was very light. Again, Khanty’s cries and dogs’ barking filled the tundra. The dogs quickly collected a herd of deer, and my driver easily caught his bulls throwing a lasso, or tynzian, over their horns. The team was ready – we could move on. Now the deer galloped from the start. ‹…› Reindeer can gallop or trot 10 to 15 kilometers. This distance depends on the reindeer strength and stamina and on how hard the road is. The deer kept running, and, again, we approached lonely tents where hot tea and frozen deer meat or fish were always ready for us. When a fire was burning, it was always warm inside a tent. In the winter, it had double covers made out of reindeer skins, or nugi, furry side in and furry side out.

From early October, when the last boat left, we were to receive no mail until it could be delivered by sledding. There were no airplanes at that time of the year either. Postal communication resumed only by late November, when, apart from planes, mail was delivered by horses‹…› Reindeer is a remarkable animal. Throughout the winter it eats nothing but reindeer moss, which it procures from under 30—40 cm deep snow and, in return, it clothes, feeds, and transports the entire northern population. How warm deer clothes are! Before the trip, I was procured with fur stockings (chizhi), over which you wear embroidered reindeer kisi (knee-high boots). Then you put on the clothes made with the furry side in – a malitsa (it is put on over the head, and men often belt it). On top of this, you can wear clothes with the fur out – a sook, or gus’ in the Russian language. The malitsa and the sook both have hoods edged with fur, the sook hood is usually edged with a polar fox tail, and it protects the face well. It is difficult to walk in these clothes but when you are on the sledge, you know that no frost can get down to you. There had not been any severe frosts there yet, and minus 30—40° did not count – indeed, you didn’t feel it.

‹…› At trading stations I communicated with Russian hunters, which was much easier. They mainly hunted for ermine and squirrel there. They chased squirrels without dogs because the snow was too deep, and looked for them knocking on trees. Ermines were trapped. I used to accompany the hunters as they went checking the traps and told them everything I knew about that animal and different ways to catch it. At one trading station I even made ice traps like the ones that had been used in the past. To make an ice trap, you have to pour some water into a bucket and put it outdoors. At a 40° frost, ice begins to form along the bucket perimeter. When the ice is 1.5 to 2 cm thick, you should cut, in the middle of the bucket, a round hole the size of an ermine hole. After that, the remaining water should be poured out and the bucket put indoors. Some time later, as soon as the ice started to melt, the ice trap can be easily taken out of the bucket: it is ready. The only thing left then is making an ermine get inside it, lured by the bait. This, however, I have not able to achieve. One can carry along with him no more than two ice traps, while a hunter will normally carry on him and set no fewer than ten ordinary traps. Many hunting techniques have become a thing of the past.

‹…› Generally, I observed the Nenets kids with interest. In all their games you could see that they lived in the tundra and among reindeer herds. Any rope in the hands of a young boy immediately turned into a tynzian, which he would throw over the dogs in the tent. Any piece of hide a two-year-old girl would crease and shave with a splinter, imitating her mother who works on hides. ‹…› Kids learn how to handle a sharp knife remarkably quickly – even in early childhood a knife is not a forbidden thing. As a rule, the Nenets eat meat holding it with their teeth and cutting a piece with a sharp knife right up to the nose, moving the knife upwards. It took me some time to master this technique, and I did it with caution, whereas kids will have acquired the skill by the age of three or four years.

In February and in March we began getting mail on the heaviest losses: the death of our close relatives and friends. In the first days and months of the war, our best young zoologists – Kaftanovskiy, Modestov, Uspenskiy – perished on the front. Under Kiev, our good friend Alesha Sergeev missed in action. We were all members of the Young Zoo Biologists Club, and became close friends at University‹…› In six weeks, the money allocated for my trips ran out, and by the end of January I returned to Salekhard. For the money earned, I bought for Tania and me a deer carcass, hides for two pairs of boots, a cut of good cloth for trousers and flannel for warm shirts. Also, I bought some sugar and other foodstuffs that could be bought at trading stations without any limitations. In Salekhard, ration cards had been introduced and all foodstuffs were rationed.

End of the first winter

‹…› I was not very pleased with the results of my first year of work. It went without saying that Dementiev (Georgiy Dementiev, 1898—1969, the acknowledged head of Soviet ornithologists) himself did not see and observe as many peregrine falcons as I did, but how could one prepare a candidate’s thesis based on observations of six nests, the more so that the biology of peregrines – these splendid falcons – had long attracted the attention of ornithologists and had been well studied as early as in the previous century? To write a thesis, I needed some comparative material, I had to go to the tundra once again. Tania’s studies of lemmings had about the same status. For quite some time, we had been thinking over a second year of work in the tundra. ‹…› It was clear that we would not be able to go back home in the spring. There was a lull at the front; victories held under Moscow did not make much difference. The situation was tense; the Germans appeared to be preparing a new assault, and in all probability, on Moscow, which they had failed to take at the first attempt.

‹…› We had to find a job involving a lot of traveling; once you were in tundra, food was not a problem, and we knew it. The issue resolved unexpectedly and easily. At the Reindeer Breeding Training College, where Tania taught, students did practical work with deer herds. Their duties included looking after fawning, vaccinating against anthrax, mortality reporting, and other livestock interventions. Tania could go to the herds on the same conditions as the students, and be paid a small salary. I, having the University money, could go with her.

‹…› Having examined the regular routes of reindeer herds, we decided to move along the watershed tundra of southern Yamal, to Yar-to Lakes and farther on to the big Yuribei River. On April 17, we left for the district center of Yar-sale, 380 kilometers away from Salekhard. ‹…› In Yar-sale, good news was in stock for us. Because much higher procurement plans for the meat to be delivered to the front were adapted, the district cooperative society decided to purchase deer in the spring and send them for the summer grazing so as to be able to fulfill the procurement plan in the fall. A herd of 200 deer had almost been formed, and I was offered to accompany it throughout the summer in the capacity of a livestock specialist, or, to be more exact, in the capacity of livestock movement recorder.

In Yar-sale, we finalized the routes of herd movement. We were anxious to go as far north as possible, to the locations where polar foxes make holes and polar owls nest, but cooperative society’s herd had a lot of sick and weak deer, so it could not make it to far-away pastures. Shepherds for the new herd were hired from the Budenny kolkhoz; therefore, Tania started working with the kolkhoz’s herd. As a result, our herds were to move not far from each other.

The Pors-Yaha trading station was four small black houses. The tiny one on the river bank was a steam bath. The others were a bakery, a warehouse, and a store. The nearest settlement was on the Ob River bank, over a hundred kilometers away, and all around stretched the white expanse of tundra.

‹…› Finally, the day of our departure came. Pors-Yaha was our last shelter with a solid roof over the head. We would come back there only in late fall, when everything was once again covered with snow, and the deer were strong enough to run 100 km a day.

‹…› Tania had already left with her shepherds, and mine were still drinking tea.

‹…› I was going to live with these people almost half year, without any connection with friends or relatives. I was excited and terrified to enter this new, almost primeval life, inadvertently breaking all the old ties.

We alternated long-distance journeys to the tundra with working in the vicinity of He-Yaga. Those days, I stayed to observe the peregrine falcon nests, and Tania, accompanied by Pon’ka, went to the tundra to catch lemmings. There were six pairs of peregrines in Sopheya and He-yaga, and some nests were less than one kilometer from each other. I had a lot of things to find out. Peregrines made no nests and laid eggs in small holes on the ground, and though permafrost was not strong on high sandy cliffs, I had to observe hatching in the severe northern conditions. Also, I was to get an idea of the peregrines’ “working day” after the young birds hatched, in the continuous light; and finally, we were especially interested in the relations between these courageous and vociferous predators and other tundra inhabitants‹…› “Hos’ tara, hos’ tara” (“We should go”) said a young Nenets as he pulled me gently by the sleeve. He had dressed already. His malitsa was girdled with a wide belt with inevitable plates, sheathes, and bear fangs on the back. As Pari explained to me later, bear fangs on a man’s belt were “optike pardon” – the same as medicine, a charm of a kind. With bear teeth hanging on the belt, a Nenets is not afraid of anything, neither wolves, nor blizzards; he is strong, brave, and he is not scared to guard deer on a dark winter night.

‹…› I climbed onto the sledge, the Nenets drove the deer ahead, snapped with a rein, and they started galloping at once. He easily jumped into the sliding sledge and sat in front of me. We flew onto a hill and were riding full speed on the tundra polished with winter winds.

‹…› All of a sudden, dogs could be heard barking, and a black silhouette of a tent came into view. The sledge stopped with a jerk, turning the team sharply, the shepherd tied the head deer to the sledge. We entered the tent. There was nobody but an old woman there: everybody, young and old, had left for the trading station the day before. The merry snappy fire and two big copper kettles boiling over it were waiting for their return. I was shown a place close to the fire. I lay down in soft hides, wrapped up in them, and slept calmly the rest of the night.

‹…› The shepherds spent all their time with the herd, helping the does to find and dig out fawns. Their helper was the old dog Ikcha, in a class by itself. She would find a fawn buried in snow but would not touch it – she barked to call the shepherd. The shepherd carefully dug the snow with a long pole, khorei, and beckoned the doe, imitating the fawn’s bleating. A worried she-deer would come running, sniff and lick the fawn, push it with its snout and make it rise on its unsteady legs. Anxious calls of does that had lost their little ones could always be heard in the herd.

‹…› On occasion, the shepherds used to shoot partridges. Eku and Pyriko trapped them. For this, from the first partridge caught they made the so-called gamdal: pierced the neck of the bird killed with a sharpened stick and stuck the stick into the ground at an elevated place. The partridge was put in the position of a cock looking around his estate. In its wedding outfit, a white cock with a bright red neck could be easily seen. Another cock would fly up to that exposed bird to fight and would get into the trap set right there. Once a polar owl got into the trap; it attacked the gamdal and gave it a good thrashing. The meat of the game caught was our food. As I entered the tent, I was surprised to see white shaggy legs and wings of very improperly plucked partridges sticking out of the kettle. Why should one pluck the hard and rigid feathers if they come off easily when the bird is cooked? I had to get used to many things.

‹…› The weather was fine. With every day, the tundra was getting rid of the snow more and more. The snow did not melt, just disappeared, evaporated in the all-day light of the sun. The deer grazed only on hill tops free from the snow. She-deer with young fawns also kept to the thawed patches: there, on the dark ground, it was warmer. Fawning was nearly over. We began moving, it was high time to change the pastures. Following the does now were dark, awkward figures of young fawns. ‹…› Partridges were belling with all their might. The cocks were fighting desperately. Each tried to approach another from the side, and the latter turned its chest to the rival. In this manner, they ran one in front of the other, moving in the same direction. I watched two partridge cocks cross in this way the whole stretch of an icy lake. From time to time, they would stop and attack each other. The cocks having no couple behaved in a very agitated manner. Roused, they flew off squawking, walked around excitedly, fluffing up their tails; it was those cocks that flew to the gamdal, which they perceived as their enemy, and got trapped. The cocks having a couple were much calmer. When you approached them, they stretched their necks, gobbled quietly and took wing only after the hen flew up. The hens were totally inconspicuous in their mottle dresses; the cocks, on the contrary, attracted attention by their defiant behavior and bright nuptial attire: white birds with red-brick necks. The colors helped to preserve the hens, which had already started to lay eggs.

The lakes began to open up only in early June, and spaces of open water among ice formed, in the first place, where small rivers or streams fell into the lakes. The ducks that had arrived (pintails, teals) and a multitude of long-tail diving ducks stuck there. On isolated lakes, ice remained much longer – as late as June 19 I observed long-tail ducks lying on the ice, soaking in the sun. The geese, which had flown in early June, fed at the banks of low grassy lakes. They tore out sedge grass and ate the succulent underground part of the stem. Eku and Pyriko switched to trapping geese. They would set a trap right in the shallow water and strew around torn-out sedge grass, imitating a feeding place.

‹…› One day, a young she-deer went lame. The following day, the leg swelled, and the doe could hardly step on it. Pari called me and said, “We should cut this doe a bit. It’s the end anyway. Today the meat is good, tomorrow bad, you cannot eat it.” I agreed; we had not had any meat for a long time. The news that we were going to slaughter a deer quickly spread to the two tents. Everybody tumbled out, discussing something noisily and brightly, dragged out wooden tubs, sharpened knives, chatting with one another. The poor she-deer was caught and led towards the tents. So as not to lose a single drop of blood, it was first strangled with a tynzian, and then its heart was stabbed with a knife – it was a flush, well-planted blow, and all the blood flew out in the interior of the body. After that, the Nenets deftly skinned it with knives, opened the peritoneum, took out the intestines and put them in a tub (those would be needed later). The she-deer was lying on the side, and the upper part of the ribs was detached, cut off along the breast bone and backbone. On the ground was the lower part of the sternum, filled with blood. There, into this natural cup, they began cutting pieces of liver, heart, the long back muscle, and other soft parts. Then everybody sat around this festive dish and, piercing blood-soaked bits of meat with a knife, delightedly put them into the mouth. All the faces were smeared with blood. Niabuku’s pretty face was stained with blood from ear to ear, and only her white teeth glittered as she smiled happily. I watched this blood feast with interest and surprise, and they were laughing at me, offering to taste this or that piece. Some would even scoop the warm blood with cups and drink it. All this was explained and justified by the historical development of the northern peoples. The raw meat and blood of recently killed animals preserved the Nenets from scurvy: they never had it. The Nenets are proof to both scurvy and colds. Life in the severe conditions of the North has made them resistant to these diseases. They suffer from other illnesses brought by the Russians (tuberculosis first and foremost), against which they have no immunity.

‹…› All life in the tundra is based on seizing a lucky moment, and spotting a flock of molted geese on a small lake was a lucky chance, which might provide game for our whole camp. It couldn’t be lost.

After another ridge, we saw the span of an oblong lake overgrown with sedge grass, and a black spot on its surface: a flock of molted geese. The Nenets did not have a lengthy discussion on how to organize the hunting: at that very moment, the deer rushed down the ridge and surrounded the lake on the two sides. The geese grew uneasy. From the top, I could see them stretching their necks and swimming towards the opposite bank, intending to flee for life. Lousoma’s sledge intercepted lines of retreat. He shouted and waved his hands, and the flock turned back. Alarmed, they swam towards the other bank – and again horrible cries stopped them. Flurrying around, they stuck together in a thick flock, and that pronounced gregarious feeling helped the Nenets to keep a flock of 150—200 geese on a small lake while preparations for fowling were underway. Shortly, a boat was floated, and the Nenets set a net across the lake. Lousoma and I couched on the opposite sides of the lake, rifles in our hands. The skein of geese was passing slowly past me. A bullet whistled and scratched the water behind the flock. “Hupta…” (“Far),” Lousoma shouted to me, and at that very moment a goose twirled and flapped its wings, hit by his bullet. I aimed a bit lower, and there it was: the biggest and most beautiful goose drooped and bent its head. “Pydor Tania” (“It’s yours),” the Nenets words came to me from the other bank. “Both mine,” I replied looking at the wind swaying and moving the birds’ shapeless, dead bodies towards me. And the geese kept swimming. We could see their heads on the bank, in the sedge grass. A woman and a dog nearby were all agog, and the mother did not hear her poor little Savone crying. “Piau – pri,” she let the dog go as soon as the geese were far away from the bank. The dog shot off. Some geese fled and hid behind the ridge; others hailed back into the water; the dog snatched one and began mauling it until the master came running.

‹…› In the meanwhile, a net was set on the other side of the lake. A small pool was netted off, and then, as the net was put down into the water, the Nenets on the boat drove the geese into it. Slowly and carefully, the geese were swimming into the pool. Out of the blue, wild shouts from the bank reached them; the Nenets hit the water with sticks, and the geese turned around; the net went up, and a few geese splashed, entangled in it. Everybody was so much carried away by the netting that nobody saw the main part of the flock get out of the lake and make it to the top of the hill. Trying to catch up with them did not make any sense. They would go to the big lake, where it would be impossible to surround and catch them. We had to get over with those left there. One goose hid in the sedge grass, and Pyriko stole up to it and hit it with a tiur. Another climbed onto the shore and tried, once again, to run for life; but he was caught up by people on the sledge; and his flapping of the wings, as he tried to escape from the deer, was all for nothing. The goose hiding in the willows was retrieved by a dog...Finally, we were there. Our catch was 43 geese: old and young, dark big bean geese and pink-beaked brants with white foreheads. On many of them I could see the bleeding pins of growing feathers. A heap of warm, not yet cooled game and feathers smeared with blood. Looking at it made me ill at ease...

‹…› The Nenets are very fond of fairy tales, but they do not have many good story-tellers. I can remember one, his name was Niaku. In the evening, in Niaku’s tent, when everybody had had tea and lain down on the khoba (winter deer hides) spread along the walls, Niaku would start his story which often lasted till midnight. ‹…› The tales were all about the same: a Nenets had three thousand deer, and he went to fowl geese, and his wife sang him a song that he should not go for the geese because he would have a misfortune. And Niaku sang largo, in a gravel voice, the wife’s song. And the Nenets did not listen to his wife and went fowling, and got many geese, a boat full, but on the way back another Nenets attacked him and killed him, and took his wife, deer, and geese. And the brother of the Nenets killed decided to revenge for his brother, and looked for the murderer for a long time, and finally found him but could not kill him because he was a shaman, and they shot arrows at each other for seven days and seven nights, and so on.

‹…› In August 1943, I came to Omsk on a boat with a snow-white deck. At that time, the Vakhtangov Theater was returning from Omsk to Moscow. In my pocket I had a note from Yuri Isakov to a school friend of his, Misha Zilov, who was in charge of the theater re-evacuation. In Omsk, I found Misha, showed him the note, and he gave me a railway ticket voucher. At the railway station, I got a ticket to a car without sleeping accommodations and hardly managed to squash onto the brake platform. I remember that before getting on the train I bought a turnip at the railway station. I munched it sitting on my sacks and felt absolutely happy.

‹…› I only remember going along the platform in Moscow and walking sprightly along the pavement with a huge rucksack on my back and a sack tied with a rope hanging on my shoulder.

‹…› The following day I went to the University. Inside, it was quiet and semi-dark, as always.

‹…› I went up to my habitual lodgment in the “cage” of the zoological museum gallery. ‹…› One day I went down to the chair room and saw, ahead of me, Alexander Nicolaevich (Alexander Formozov, 1893—1973, an outstanding Soviet zoologist, Varia’s professor and future husband) striding bouncingly towards the comparative anatomy hall.

At the same time, a letter from A.N. Formozov came with some advice on work, written back in September. This letter encouraged me greatly, and the doubts that my scientific work was not needed disappeared“Shall I call him? No, I’d rather not. What shall I tell him?” I dashed upstairs, to the gallery, and put my nose back in the books. Some time later, I heard his steps on the iron staircase. He was told in the chair room that I had arrived and came looking for me. I ran up to him in my brown Salekhard dress.

– Hello, Alexander Nicolaevich!

He smiled.

– May I kiss you?

There was no answer; we just kissed each other on the steep staircase of the Zoological Museum.