My AP

"Dedicated to the 100th anniversary of my teacher Academician Aleksey P. Okladnikov...

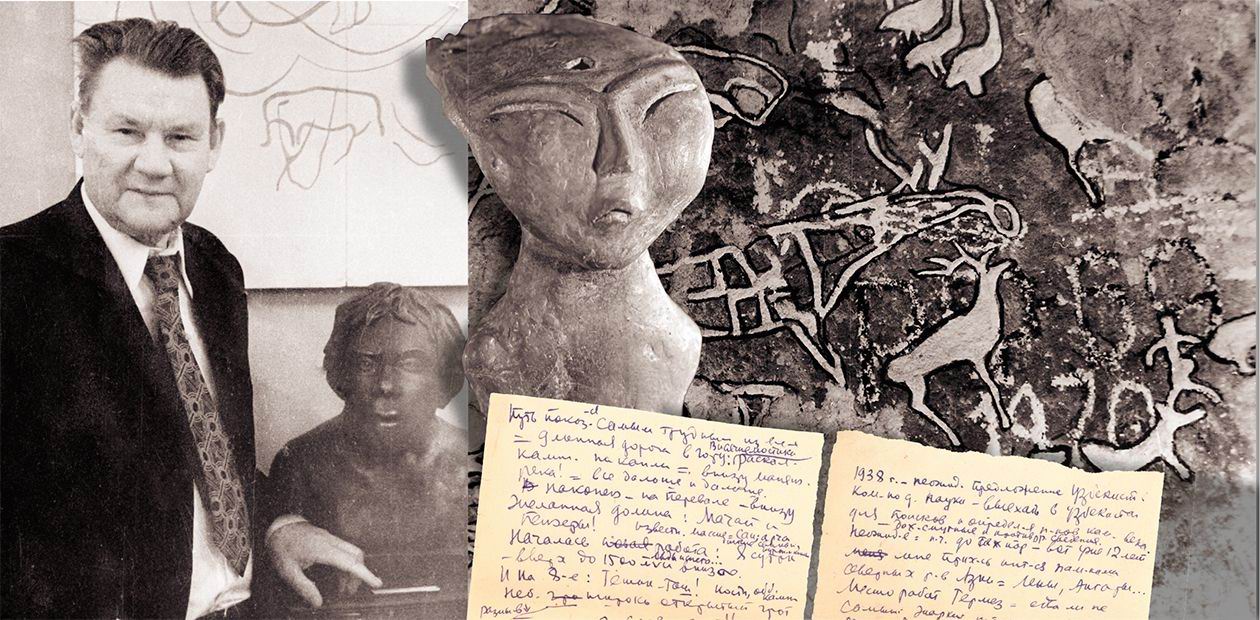

In the 1960s—1970s, the name of the Soviet archaeologist, Hero of the Socialist Labor Academician Aleksey Pavlovich Okladnikov was well-known both in the Soviet Union and abroad. It was my good fortune that I worked together with him for twelve years at the Institute of History, Philology and Philosophy, Siberian Branch of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, which he founded in 1965. As a member of expeditions headed by him, I had a chance to see many monuments that later became the classics of archaeological studies. Mountains and plateaus, steppes and forest steppes, plains and lowlands of the Altai, East and West Siberia, Cis-Baikal and Trans-Baikal regions, enormous expanse of the Russian Far East—Aleksey Pavlovich saw them all, and everywhere he made archaeological discoveries, stretching the history of Siberia and Far East both in width and in depth..."

Dedicated to the 100th anniversary of my teacher Academician

Aleksey P. Okladnikov

To AP

Our years weave into ages

And ages weave into epochs.

Human life is so short,

A tiny dot in the scale of eternity.

Each of us though

Craves leaving a trace after him

Making the best of his short life

And winning a bit of glory for his deeds.

Not everyone will spot a shimmer of Hope

Or the delight of Happiness.

Only he who can see the Future through the ages

Will become the Genius of his epoch.

You have found the hidden key to the Past,

And blazed a trail across the centuries,

So that we could walk in your footstep

And find Future amid the Past.

Year 2008

In the 1960s—1970s, the name of the Soviet archaeologist, Hero of the Socialist Labor Academician Aleksey Pavlovich Okladnikov was well-known both in the Soviet Union and abroad. It was my good fortune that I worked together with him for twelve years at the Institute of History, Philology and Philosophy, Siberian Branch of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, which he founded in 1965. As a member of expeditions headed by him, I had a chance to see many monuments that later became the classics of archaeological studies. Mountains and plateaus, steppes and forest steppes, plains and lowlands of the Altai, East and West Siberia, Cis-Baikal and Trans-Baikal regions, enormous expanse of the Russian Far East—Aleksey Pavlovich saw them all, and everywhere he made archaeological discoveries, stretching the history of Siberia and Far East both in width and in depth.

When he was not around, everybody at the Institute called him just AP.

In the late 1960s—1970s, responding to the call of his restless “vagrant” soul, he would rush to the fields any time of the year, getting together a small mobile team. And we, who were lucky to be at his side, also left “for a couple of weeks” to come back home in the late fall or early winter. Expedition life in those days was, as AP used to say, “Spartan and simple like that of Suvorov’s soldiers”. It would take half an hour to arrange a field trip and pack our meager belongings. Five to six people shared a tent, sleeping in bags or just on the earth covered with tarpaulin, with or without some dry grass underneath. Our cooking was plain and quick, done over a fire or on a soldering lamp, and our dining room was space in front of the tents. Sometimes, when we were carried away by work, we could do just with tea.

Out in the field, AP was indefatigable and always in action. The earliest riser, he would wake up those who were next to him, murmuring gently: “Will you get up, my dear? Look, what a lovely morning! You risk missing the manna. Take a spade, will you? Let’s go and dig a bit before breakfast.”

If he saw that somebody “had slowed down or was daydreaming”, he would immediately make him or her do something. Everything around him went with a swing, buzzed with excitement and throbbed with life. He was in constant search. He would walk, hands clutched at the back, bent forward, peeping down and scanning the environs, looking about for traces of the remote past, known to him alone.

“… When we were in Nizhneudinsk, we first heard somewhat muddled stories about a local maverick. This eccentric school teacher was the only one in that locality who knew something about petroglyphs on the Uda; moreover, he had their photos and sketches and had been to the caves … We saw at once that he was obsessed with a pure passion for scientific adventure and discovery… Such people are often misunderstood even by the dear ones; their obsession hinders the well-being of their families and disrupts comfortable life. And yet, they sparkle like precious stones against the background of everyday routine, with all their eccentricities, continuous restlessness and enthusiasm. And nothing can make them turn back. This teacher whose name was as amazing and unpredictable as himself—Pugachev—belonged to the breed” (Discovery of Siberia by A. P. Okladnikov)He used to dig with a spade, on equal terms with the others, and skillfully cleaned the walls of the digging pit using a scoop and a knife, to reveal stratigraphy. He would carefully brush away the earth around an artifact found, examine it closely, make a sketch, and put down its description in the expedition diary. When the stone artifacts discovered were many (for instance, dozens thousands in Mongolia), he would make everybody make sketches, including drivers, whom he trained then and there. The most precious findings, of course, he drew himself or entrusted to somebody who could masterly bring out the texture of an artifact.

“…In February 1974, the village of Khudoelan, where I worked as a teacher, was unexpectedly visited by the well-known scholar and archaeologist A. P. Okladnikov. We had a talk, and he explained why he came to see me. In early 1973 he read my article about the Yarma carvings, written as far back as in 1965. The newspaper where the article was printed was passed over to him by the philologist V. I. Rassadin, who was studying the Toph language and often visited Tophalaria (the Sayany mountains)—and this was where we met and made friends.During the same summer, A. P. Okladnikov sent to Nizhneudinsk Candidate of History А. Mazin on a mission to copy the sketches and find out when an expedition could be organized to our locality. Mazin fulfilled his task and learnt that Yarma was accessible only in winter when the Uda River was ice-bound. At the beginning of the following year, A. P. Okladnikov launched a winter expedition to Nizhneudinsk in order to examine the Yarma petroglyphs. After the expedition work was over, he came over to Khudoelan.

It took Aleksey Pavlovich only a few minutes to make a good impression on his audience —he was gentle, respectful and tactful. First he told us about his work and his trip to the Yarma rapids, spoke well of the importance of our discovery, and when he learnt that the school had a regional studies club, suggested organizing a summer expedition to the valley of the Uda River to look for more rock carvings and maybe even ancient sites. Needless to say, I agreed readily, the more so that Aleksey Pavlovich promised to give us advice and familiarize with the methodology of archaeological search.

…This meeting was especially memorable. I found out so much about archaeology and rock painting! A. P. Okladnikov told us about the technique ancient artists—hunters used to make petroglyphs, explained the meaning, ideas and symbols an ancient artist put into his carvings. Most importantly, this meeting made me revalue my searching activities, which, as it seemed, were totally useless; it gave me new inspiration and interest in the surrounding world, which was beginning to go away.” (from memoirs by M. I. Pugachev)

From my viewpoint, AP was easy to communicate, open and accessible for everyone. He was interested in the everyday life of each member of his team. Equally nice to everyone, he would quickly make friends with schoolchildren and teachers, beginner scholars and luminaries of science, shepherds and party nomenclature, border guards and soldiers, pilots and sailors, workers and peasants. Neither of us took it as something extraordinary—we thought it only natural that a great scholar should be a great man. His field clothes were as unpretentious as his manners: a dark blue or black work-day outfit (the kind fitters used to wear), boxcalf boots, an old hat or a cap with a big visor. His friends used to call him “Academician in boxcalf boots”.

“We can state without any exaggeration that rock painting is a window to the world long gone, looking through which you can get into the most hidden and intimate corners of ancient culture. It is hence not surprising that petroglyphs have been the focus of attention of those who want to peep into the very soul of the ancient man, grasp his mentality and art, his aesthetic ideas and ethic standards, his views of himself and the world around him, and of the Universe”, wrote A. P. Okladnikov in one of his works on the importance of rock paintingThroughout his long life, AP had lots of disciples and followers, who worked side by side with him for some time and learned from him the intricacies of life and archaeology. Each of them can tell his or her own story and create their own portraits of the teacher. I am one of those who saw him almost every day, in the field and at home, in the last twelve years of his life. Sometimes my camera helped me to stop the time and fix the image of Aleksey Pavlovich for history. It was not an easy task to make photos of him though. When he noticed the camera, he would wave his hand and say, “Vovik, don’t spoil the film!” So these moments were rare…

The publication uses photos from V. P. Mylnikov’s archive and materials of the St Petersburg Branch of the Archives of the Russian Academy of Sciences.