The Soul’s Despairing Cry

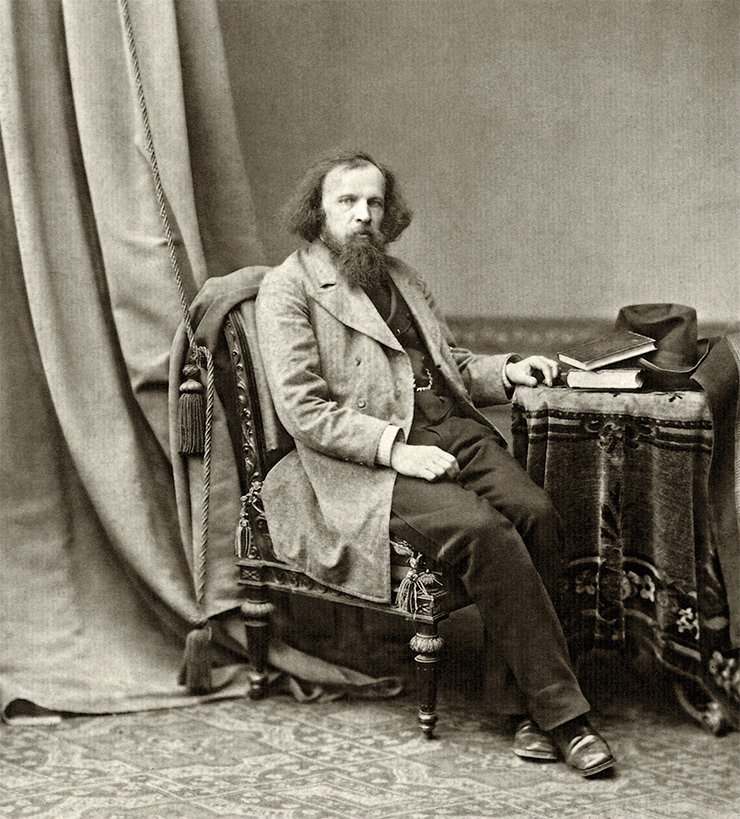

When this review about the outstanding Russian chemist D.I. Mendeleev (1834—1907) was prepared a variety of literary and archival materials were used. It presents a view on the main events in the life and activity of the scientist that somewhat differs from that adopted in historical and scientific literature. The author of this article is a well-known St. Petersburg scientist, philosopher and historian of science, director of D.I. Mendeleev Museum & Archives SPbGU, a 100th anniversary of which will be celebrated this year

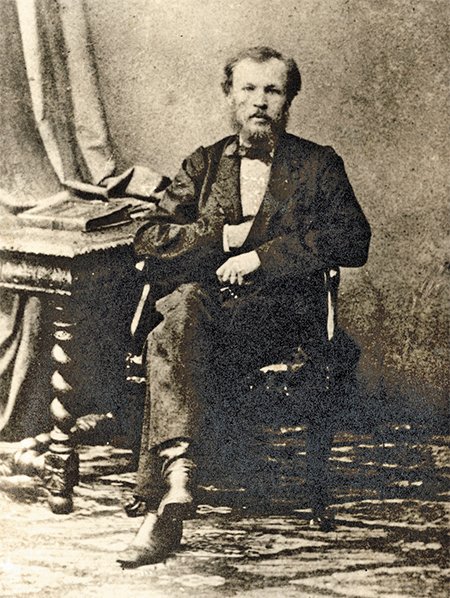

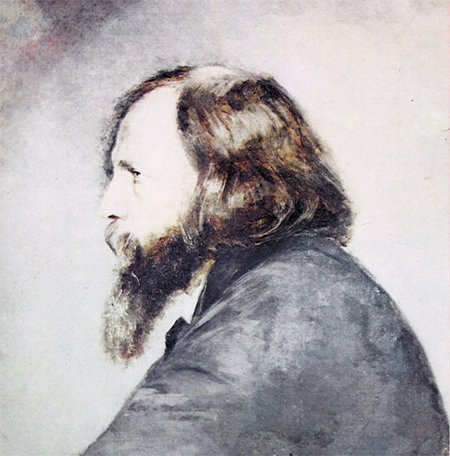

Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev lived a long life rich in events, great flashes of inspiration and heartbreaking disappointments. The year he was born natural philosophers John Dalton (1766—1844) and Jacob Berzelius (1779—1848) were still alive; A. S. Pushkin had not yet completed “The Captain’s Daughter.” By the time of his death, the spouses Curie and A. Becquerel received the Nobel prize (1903) for their investigation of radioactivity, A. Einstein had already written his famous article “On the electrodynamics of moving bodies” (1905), while V. V. Mayakovsky and M. I. Tsvetaeva started their first poetic experience. Mendeleev had a long and complex dialogue with his epoch. He might not have heard or understood everything about the time in which he happened to live, but the era was not able to fully appreciate his ideas, troubles and insights either.

Escaping “Latin self-delusion”

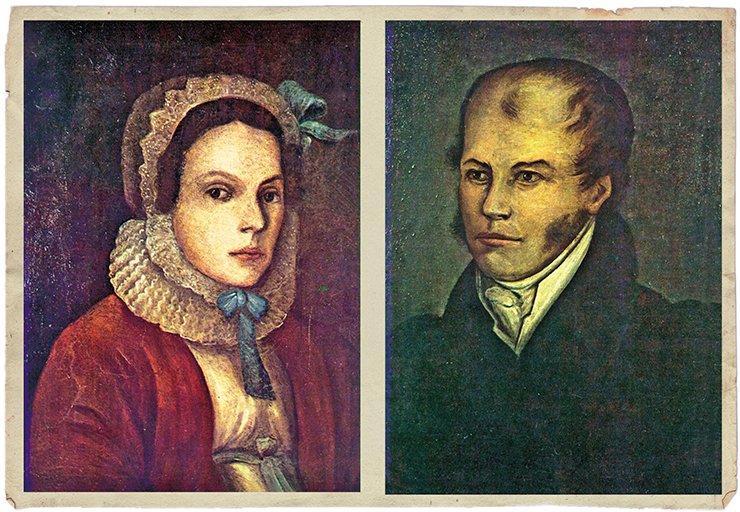

Born on 27 January, 1834, Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev became the last, seventeenth child in the family of Ivan Pavlovich Mendeleev, the director of the Tobolsk classical gymnasium. By no means all of his brothers and sisters lived to their thirties, with eight of them dying in their infancy.

The question of the origin of Mendeleev’s family name is quite often raised. Ivan Pavlovich was the son of a priest Pavel Maximovich Sokolov. Following the tradition of that time, all four sons of the priest were given different family names, with the scientist’s father receiving the family name of a neighbouring landlord.

The year his last son was born, Ivan Pavlovich started getting blind and thus had to resign from service. Soon other illnesses followed, and in October 1847 Mendeleev’s father died leaving his wife Maria Dmitrievna Mendeleeva (ne’e Kornilieva) alone to support her family.

She belonged to a well-known family of Siberian merchants, the first mention of which goes back to the 17th c. Vasiliy Yakovlevich Korniliev and his son Dmitri “were the first to start building factories in Tobolsk, a paper mill and crystal factory.” In 1787, “simultaneously with Franklin in America,” they established a printing house, which started publishing a monthly magazine The Irtysh and books (Family chronicle, 1908, p. 135).

Maria Dmitrievna’s brother Vasily managed the estate of the Trubetskoy princes (Pushkin called him “our brother Korniliy”) granted his sister a power of attorney to manage a small glasswork built near Tobolsk by the merchants Korniliev as early as in 1750. In the beginning everything went well but in June 1848 the plant burnt down, and Maria Dmitrievna decided that she “can leave Tobolsk without any regret when time comes to take Pasha and Mitya to the university” (ibid., p. 81—82).

Mendeleev’s childhood coincided with the time the Decembrists served their prison term in exile in Siberia. Some of them were living in Tobolsk and its vicinity: for example, I. A. Annenkov who served in the office of the provincial administration or A. N. Muraviev as Tobolsk civil governor. Many of the Decembrists befriended the Mendeleev’s family. One of Dmitri Ivanovich’s sisters married N. V. Basargin, a member of the Southern society of the Decembrists.

Young Mendeleev did not excel at the gymnasium, progressing particularly slowly in Latin and German. As he himself remembered in his old age, “I was always bad at German but the mark turned out to be good enough for graduation because when answering at the final examination, I luckily managed to remeber some verses by Schiller with which I was familiar; I liked the sound and the meaning of them, which somebody explained to me.” (Mladentsev, Tyshchenko, 1938, p. 48). Sometimes, Dmitri coaxed Masha, who was married to the teacher of Tobolsk Gymnasium, to find out what they would ask during the exams.

In any case, in June 1849 Mendeleev graduated from the Gymnasium. By then Maria Dmitrievna was left with two children, Dmitri and Elizaveta (the others left for different places). She went with them to Moscow, hoping to assist her junior (the reckling) in getting into university. However, according to the rules of that time, Mendeleev could only go to Kazan University because Tobolsk Gymnasium belonged to Kazan educational district. Maria Dmitrievna hoped that her brother’s connections would help, but it did not work out. She rejected categorically the suggestion to get Dmitri a job in the Governor’s office – it was not the career she anticipated for her youngest son, who she brought to Moscow spending her last money. That was why in the spring of 1850 the Mendeleevs went to Petersburg.

“Pedagogical, so it seems to be named...”

As expected, Dmitri was denied enrolment at Petersburg University. He was not yet certain about his calling and in the end went to the Pedagogical Institute (he had an idea to enter the Medical Surgical Academy but fainted while in the dissecting room).

The Main Pedagogical Institute shared not only the building with Petersburg University (they were both located in the building of Twelve Collegia commissioned by Peter the Great) but, what is more important, the faculty, which at the time included such well-known scientists as the physicist E. H. Lentz, biologist F. F. Brandt, mathematician M. V. Ostrogradsky and chemist A. A. Voskresensky.

“To a certain extent it was considered blameworthy to get prepared for the exams, and though we usually worked a lot, during the exams we played cards all nights through and looked down upon those who were revising for them” (D. I. Mendeleev)As Mendeleev later confessed, “[I] myself am obliged to the Main Pedagogical Institute for my progress as a whole” (Mendeleev, 1995, p. 278); however, in the beginning it was very difficult for him to study. In September the same year Maria Dmitrievna died and in spring 1852 his sister Elizaveta died too. Having been left completely alone in an alien and cold Petersburg, the young student frequently fell ill; he started spitting blood, and the institute doctor thought that Mendeleev was going to die. Fortunately, he escaped consumption and got better. As he was recovering, he started spending more and more time studying.

The choice of topics for Mendeleev’s first papers, reports and independent research studies was surprisingly diverse: “Historical description of Tobolsk,” “On secondary education in China,” “On fossil plants,” “On physical education of children from birth to the age of seven,” “Experimental study of rodents in St. Petersburg province,” “Chemical analysis of orthite in Finland” and so on.

Already in his student papers such important features of Mendeleev’s creativity became apparent as his interest in a broad variety of topics and the focus on the most difficult, global problems. In his diploma thesis (On isomorphism in connection with other relations between crystalline forms and chemical composition, 1855) and Master’s thesis (On specific volumes, 1856), the young scientist raised the problems which were unsolvable the way they were formulated either then or now. But for him as a natural philosopher it was not so important to reach the goal but rather to see as much as possible on the way to it.

“Delicate experiments” in Germany

In 1859 Mendeleev got a chance to go to Germany on an internship abroad paid for by St. Petersburg University. He chose Heidelberg University, where such celebrated German scientists as Robert Bunsen, Gustav Kirchhoff, and Emil Erlenmeyer were teaching. However, Mendeleev found it impossible for him to work in the laboratory of the “old chap Bunsen.” As he explained in his letter to his friend and co-worker L. N. Shishkov, “there is nothing necessary for work in this laboratory; even the scales are quite poor; more importantly though is that there is no clean and quiet corner in this laboratory where I could conduct … delicate experiments… Unfortunately, the interests of this laboratory do not go beyond the level of secondary school problems: a great number of employees are beginners. I decided to set everything up at home” (Mladentsev, Tyshchenko, 1938, pp. 159—160).

Out of two years Mendeleev stayed abroad, he spent almost half a year travelling around Europe. He made some of the trips together with I. M. Sechenov and A. P. Borodin, young scientists with whom Mendeleev became close in Heidelberg. The aims of their trips were quite varied: to buy equipment and reagents in Paris (“I had some business to do and also we had some fun there,” he demurely wrote to his future wife), to take part in the First international Chemical Congress in Karlsruhe (1860), just to admire the sights of Switzerland and Italy.

Out of two years Mendeleev stayed abroad, he spent almost half a year travelling around Europe. He made some of the trips together with I. M. Sechenov and A. P. Borodin, young scientists with whom Mendeleev became close in Heidelberg. The aims of their trips were quite varied: to buy equipment and reagents in Paris (“I had some business to do and also we had some fun there,” he demurely wrote to his future wife), to take part in the First international Chemical Congress in Karlsruhe (1860), just to admire the sights of Switzerland and Italy.

Many years later, when answering the question why he took on so much work after returning to Russia, Mendeleev replied in his usual simple and sincere manner: “when I lived abroad, I had an amourette and for its fruit I had to pay” (ibid., p. 209). It refers to the Heidelberg love story of Mendeleev with a provincial German actress Agnessa Feuchtman, from whom he had a daughter Rosamunda. The “young father” had to borrow 1000 roubles from I. A. Vyshnegradsky, his acquaintance from the Pedagogical Institute, who later became the Russian Minister of Finance. It should be admitted that this story caused a lot of trouble for Dmitri Ivanovich: “All my troubles are caused by the fact that my wishes do not always follow my mind … sometimes I follow my heart and thus follow Feuchtman instead of running away…” (Mendeleev, 1951, p. 116).

As for his “delicate experiments,” although the study of capillarity Mendeleev conducted in Germany gave some interesting results, the main question concerning the connection between the liquid tension, its density, molecular mass and chemical composition remained unanswered. Having understood the theoretical hopelessness of further research, Mendeleev set for himself perhaps an even grander goal: “to find the dependence between the coupling determined from capillarity and the coefficient of expansion… A complete solution of this problem is very complicated. <…> But the complexity of work does not scare me, even if the “desired result” is not achieved” (Mladentsev, Tyshchenko, 1938, p. 232).

It is hard to say where his program of research which did not promise to achieve the “desired result” would have led him, but he got extremely “lucky” – in January 1861 his request for the extension of his trip was denied. “In the morning [the experiment] with glycol expansion was going so well when the letter from Iliyn saying that my trip would not be extended for another year was delivered,” Mendeleev wrote in his diary discontentedly (Mendeleev, 1951, p. 115). So, he had to return to Russia.

There, the situation with young scientists was completely different from that abroad, which Mendeleev wrote frankly and inexorably about to the trustee of the Petersburg educational district: “it is difficult to pursue science in Russia, with our chemists being a living proof of it… All of them managed to achieve a lot during their two to three years stay abroad… Compared with such a short period of time, they have lived in Russia for a long time but their productivity is low despite the fact that their interest in science and their wishes have often stayed the same or even developed further. There are many reasons for this. But, of course, the main two are lack of time and lack of textbooks necessary for work. <…> After returning to Russia, I will have to become an associate professor without a salary and thus will again have to earn a living by private tutoring and delivering lectures” (Mladentsev, Tyshchenko, 1938, pp. 224—225).

“In my lifetime I have known a great many Russian bureaucrats and can assert with certainty that a good half of them do not believe in Russia, do not love Russia and understand the Russian people rather poorly, although everybody … do things at his/her own risk or, putting it more clearly, theoretically justify their thoughts and actions” (D. I. Mendeleev)Indeed this was what happened. Despite the request made by the department of physics and mathematics, the University’s Council rejected the candidate because of a lack of financing. Maybe, the reason was that some of the university faculty failed to understand fully the goals and objectives of Mendeleev’s research. This was what Iliyn mentions in his letter: “Lents… said that there was no particular need to go abroad to do something you are doing at present” (ibid., p. 237).

Thus, Mendeleev’s extensive research plans were not meant to be fulfilled. Sechenov, who returned home a year earlier, turned out to be right: “Spent the days of [Lent] in Moscow, signore miei Mendeleev and Borodin, and that is why am answering with a little delay… The Holy Russia is in a state of great mess. Petersburg audience has lost interest in science… Do not be surprised at my bad mood – I would like to see what you will say when you return home yourself” (ibid., p. 16).

Hence after returning to Russia, Dmitri Ivanovich had to look for means for survival rather than focus on his research plans. However, such rude intrusion of the social situation in cognitive history had its advantages too as the events that followed showed.

“What sort of a person am I, by golly?”

Since it was improbable that some teaching position would open in the middle of the academic year; the only way to earn a living was to do literary work.

Only a week after his return to Russia, Mendeleev reached an agreement with the publishing house Obshchestvennaya polza (“Common good”) about translating the manual written by I. R. Wagner, a professor of technology at Würzburg University. In the process of work it turned out that “in many places” it was necessary to “considerably supplement or change the <text> to give it a tone to make it meet the requirements of our readership” (Mendeleev, Col. Works in 25 vol., vol. 8, p. 49). From 1862 to 1869, eight issues of the encyclopaedia were published but only two of them contained Mendeleev’s articles. He wrote about the other issues that “having no time to translate and compile new issues of The Technical Encyclopaedia, I invited technologists. However, soon I had to give up the whole project because I was not paid at all for my work, and the publishers got disinterested in the project. I am haunted by the idea of how useful and important a technical encyclopaedia is but I am not good at making the project profitable” (D. I. Mendeleev Archive, 1951, pp. 51—52).

Only a week after his return to Russia, Mendeleev reached an agreement with the publishing house Obshchestvennaya polza (“Common good”) about translating the manual written by I. R. Wagner, a professor of technology at Würzburg University. In the process of work it turned out that “in many places” it was necessary to “considerably supplement or change the <text> to give it a tone to make it meet the requirements of our readership” (Mendeleev, Col. Works in 25 vol., vol. 8, p. 49). From 1862 to 1869, eight issues of the encyclopaedia were published but only two of them contained Mendeleev’s articles. He wrote about the other issues that “having no time to translate and compile new issues of The Technical Encyclopaedia, I invited technologists. However, soon I had to give up the whole project because I was not paid at all for my work, and the publishers got disinterested in the project. I am haunted by the idea of how useful and important a technical encyclopaedia is but I am not good at making the project profitable” (D. I. Mendeleev Archive, 1951, pp. 51—52).

With the start of the new academic year Dmitri Ivanovich started devoting a lot of time to pedagogical activity (to a certain extent it was a desperate measure). Since autumn 1861, he was teaching at Saint-Petersburg University, the Institute of the Corps of Railroad Engineers, Nikolaevsk Engineering Academy and College and the 2nd Cadet Corps. “Running around like mad,” Mendeleev complained “hope I would not ruin myself. But there is also a good thing about it – you learn to present your ideas, see what is missing” (Mendeleev, 1951, p. 167).

Opinions about Mendeleev as a lecturer and teacher of his contemporaries differed considerably. In the opinion of the physicist B. P. Veinberg, his lectures were interesting because “they are always based on the philosophy of his scientific outlook,” with frequent digressions to different fields of “mechanics, physics, astronomy, astrophysics, cosmogony, meteorology, geology, physiology of animals and plants, agronomy as well as different kinds of technology, aeronautics and artillery” (D. I. Mendeleev in the recollections of contemporaries, 1973).

V. E. Grum-Grzhimailo, the brother of a well-known geographer and zoologist, who attended Mendeleev’s lecture on water, pointed out that he “passed to his students his ability to observe and reflect which no book can give. <…> The educators who make a box with twenty pieces of handheld luggage from engineers are afraid to leave something out … not to supply students with recipes for the rest of their lives… When Mendeleev was teaching <students> to think chemically, he did not only his job, not only what a whole cycle of chemical sciences had to do, but he did the job of the natural studies department as a whole” (ibid., pp. 122—123).

V. E. Grum-Grzhimailo, the brother of a well-known geographer and zoologist, who attended Mendeleev’s lecture on water, pointed out that he “passed to his students his ability to observe and reflect which no book can give. <…> The educators who make a box with twenty pieces of handheld luggage from engineers are afraid to leave something out … not to supply students with recipes for the rest of their lives… When Mendeleev was teaching <students> to think chemically, he did not only his job, not only what a whole cycle of chemical sciences had to do, but he did the job of the natural studies department as a whole” (ibid., pp. 122—123).

And here is the opinion of the biologist A. M. Nikolski about Mendeleev: “I am ashamed to say, but I did not like him either as a professor or a person. <…> There was something theatrical in his manner of speech, as if he were showing off his celebrity status. <…> At one of the Congresses of Russian Naturalists held in the University Assembly Hall and attended by a large number of people, he was making a speech in which he compared gold and hydrogen. Generally, his presentation contained a lot of rudiments… But in the end he made the following comparison between them: similarly to hydrogen, which can evaporate from air-tight vessels, gold can disappear from locked trunks. The speech was met with a round of applause. N. M. Sibirtsev, in the future a well-known soil scientist who was standing next to me, could not help pointing out that Mendeleev’s speech was “good for such magazines as “Jester” (“Shut”) or “Dragonfly” (“Strekoza”)” (From the history of biological sciences, 1966, p. 83).

In January 1864, Mendeleev was approved as the Professor of Chemistry at Technological Institute. The next year, upon successful defence of his doctoral thesis “Compound of Alcohol with Water,” Mendeleev became the Professor of Chemistry at St. Petersburg University. The same year he purchased the estate Boblovo in Moscow province, 18 kilometres from Klin, to which he started devoting a good deal of his time and effort. Here, he carried out investigations in agrochemistry and agriculture.

“I am only longing for peace and quiet...” Judging from the diary entries dating from the beginning of 1860s, Mendeleev was thinking about familiarising himself with plant work. Most probably the position in question was that of a manager at some enterprise – he received such proposals.In August 1863 the oil industrialist V. A. Kokorev offered the young scientist to visit the plants producing lamp oil from oil and kir in the roundabouts of Baku, which yielded losses of no less than 200,000 roubles a year. In Mendeleev’s memoirs we read the following, “Either help to eliminate losses or shut down the plant,” he said and gave me a whole thousand roubles to help him find out about this case and possibly improve the state of affairs over a short period of time I had at my disposal. I eagerly started my enquiry not only because a thousand roubles for me then, already a family man with the salary of only 1,500 roubles, played into my hands but especially because I was very much interested in this case.

On the site I tried to improve what was possible and gave pieces of advice, and in a year it turned out that a net revenue of more than 200,000 roubles was gained. Then V. A. Kokorev comes to me and offers to go to Baku to improve his business, receive 10,000 roubles annually, up to 5 % from net income calculated the same way as this year. Without hesitation I refused which, of course, an Englishman, a Frenchman or a German person would not have done had he been in my place. So, clever V. A. Kokorev started interrogating me about the reasons for my refusal, rejected all of them (about a retirement benefit, an opportunity to work for science and so on) or excuses and quite rightly concluded that it was because of haughty manners which make it very difficult for Russia to move ahead (Mendeleev, 1995, p. 388).

No matter how paradoxical it sounds, but energetic, mobile, sober-minded Mendeleev did not want to work in industry mostly because he was afraid of risk, an indispensable component of any business activity. There is an entry in his diary, “Lectures start today. <…> Should not I give up this idea about the plants and so on? They will also take my time; it is necessary to take risks, and here there is no risk at all” (Mendeleev, 1951, p. 220).

Despite his passionate nature, love for travel and trips, despite the depth of his interest in industrial affairs and all the seeming “detachment from the worldliness of existence,” “peace and liberty,” he valued the assured feeling of stability and comfort most of all. Each time chaos and bustle intruded in his life always full of activity and internally strained but “stable and orderly,” the psychological condition of Dmitry Ivanovich and often his physical condition worsened drastically.

“I only long for piece and quiet, piece and quiet and nothing else,” he wrote to his first wife (Tyshchenko, Mladentsev, 1993, p. 336). Without doubt, he referred to piece and quiet not as idleness but as an opportunity for hard, quiet and concentrated work.

Dmitri Ivanovich completely reconstructed the estate: built a cattle yard and stables and purchased agricultural machinery; he actively started participating in the work of Free Economic Society (FES), the first non-governmental organisation in Russia established by Catherine the Great for the purposes of dissimilating information useful for farming. In December 1868, Mendeleev together with N. V. Vereshchagin, the brother of a well-known artist, made a trip to Bezhetsk uezd (county) in Tverskaya province to study the production of milk products and visited an exemplary farm of N. S. Serov. The scientist’s interest in agriculture turned out to be so deep that it did not weaken even while he was in the process of discovering the Periodic Law and developing the theory of periodicity.

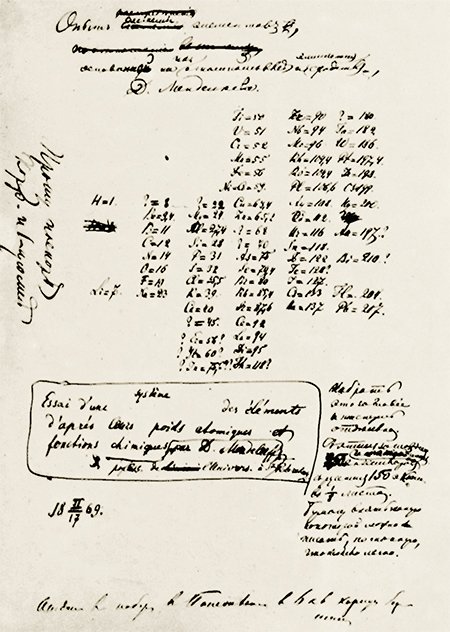

February 17, 1869 went down in history as the Day of discovery of the Periodic Law. It was the first day of his vacation, which Mendeleev took to inspecting cheese dairy cooperatives in Tverskaya Province. In the morning he received a letter from A. I. Khodnev, FES secretary, about the forthcoming trip, but then during the day he worked on compiling the table “System of Elements…” Until the end of the month he was working on the article “The correlation between the properties of elements and their atomic weight,“ which he then passed to N. A. Menshutkin for publication in the Journal of the Russian Chemical Society and for its presentation at the forthcoming meeting of RCS. Having sent the printed copies of the table to Russian and foreign chemists, he left Petersburg on March 1 to inspect the cheese dairies (Dobrotin et al., 1984, pp. 108—110).

February 17, 1869 went down in history as the Day of discovery of the Periodic Law. It was the first day of his vacation, which Mendeleev took to inspecting cheese dairy cooperatives in Tverskaya Province. In the morning he received a letter from A. I. Khodnev, FES secretary, about the forthcoming trip, but then during the day he worked on compiling the table “System of Elements…” Until the end of the month he was working on the article “The correlation between the properties of elements and their atomic weight,“ which he then passed to N. A. Menshutkin for publication in the Journal of the Russian Chemical Society and for its presentation at the forthcoming meeting of RCS. Having sent the printed copies of the table to Russian and foreign chemists, he left Petersburg on March 1 to inspect the cheese dairies (Dobrotin et al., 1984, pp. 108—110).

It was an unprecedented case! The author of the greatest discovery in the history of science, being in a good health and realizing quite well the significance of his achievement, asks his friend to make the first public presentation for the audience of professional chemists. Maybe, Mendeleev made a report about his discovery immediately upon his return from the trip? On March 20 and April 10, he made a report but it was … about cheese making cooperatives and profitability of dairy cattle breeding. More than that, at the Division of Chemistry at the Second Congress of Russian Naturalists in August 1869, in addition to making a report “On atomic volume of simple bodies,” he gave the results of chemical tests of soil in four regions of Russia.

It does not mean, of course, that during these months he did not devote any time to the study of the Periodic Law. On the contrary, from March 1869 to December 1871 Mendeleev developed the most important aspects of the theory of periodicity and defined the directions of future research in this field (see Dmitriev, The Periodic Law… 2001 for detail). Nevertheless, his works devoted to the Periodic Law were so tightly interconnected with his other, non-chemical, research that sometimes it is difficult to say which direction was the most important for him.

“I am a free Cossack”

Probably had any other scientist been in Mendeleev’s place, he would have devoted the rest of his life to elaborating the periodicity concept, considering that the field for such studies was practically unlimited. But in December 1871 Mendeleev drastically changed the subject of his research. He started investigating the physics of gases under low pressure, because this was where he saw a solution to such “paramount questions of science” as the determination of the borders of the Earth’s atmosphere, the limits of applicability of the notion of ideal gas and the existence as well as the physical and chemical properties of the universal ether, which seems to have been the most important question for him.

“Russian people are used to getting everything ready, as a present, so to say, from anybody, either from the top or from the bottom, and if manna from heaven is not falling, then we are used to blaming someone from the top or the bottom for this, without doing anything ourselves if it is connected with the necessity to make a personal effort, to risk and to persevere” (D. I. Mendeleev)Initially Mendeleev’s investigation of gases was “desk study” in character, but after P. A. Kochubey, the president of the Emperor’s Russian Technical Society (RTS), got acquainted with Mendeleev’s research, new perspectives opened up for the scientist. Thanks to the efforts of Kochubey and the Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich (the honorary chairman of RTS), the Military and Naval Ministries allocated 5000 roubles each for Mendeleev’s research. A special commission chaired by the Academician A. V. Gadolin was created to assist Mendeleev with this work. From the very beginning it was agreed that Mendeleev would study the behaviour of gases not only at a very low but also at a high pressure. The latter was of particular interest to the military. It seems everything was quite all right. But soon “misunderstandings” started.

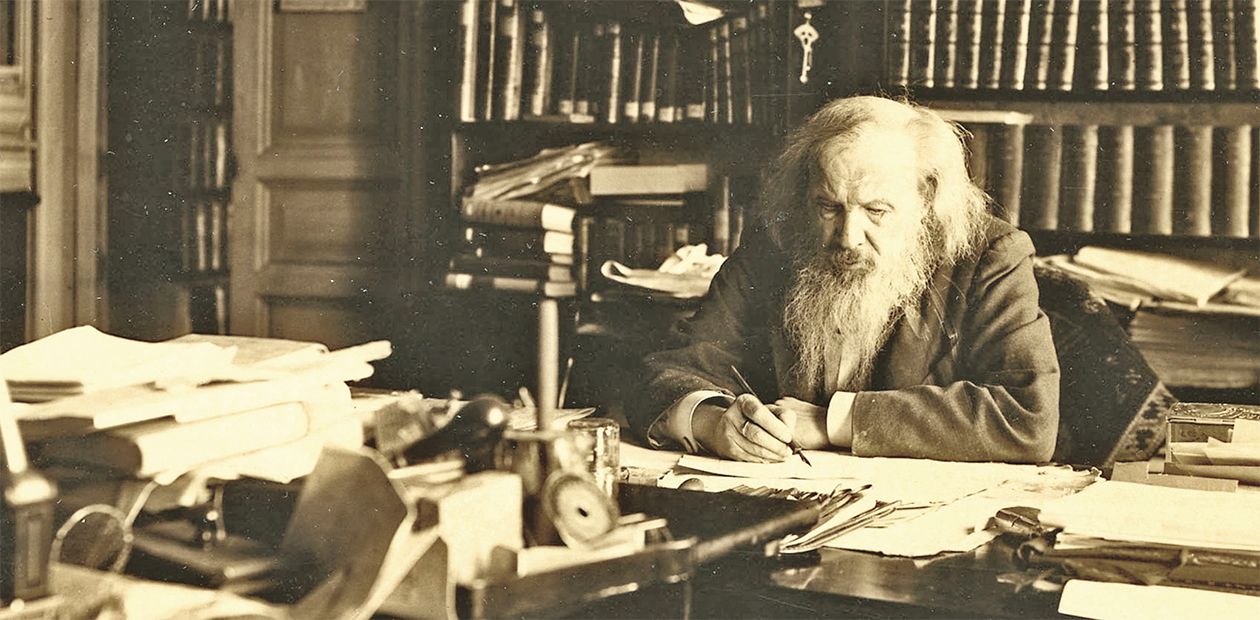

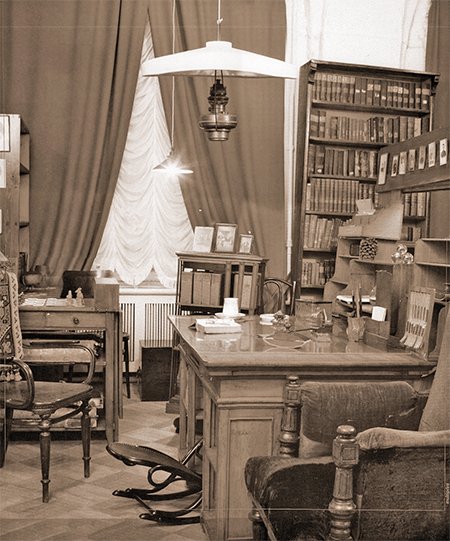

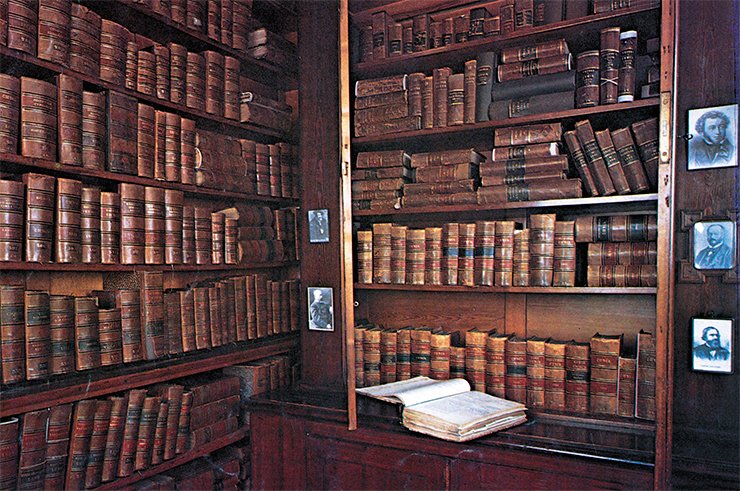

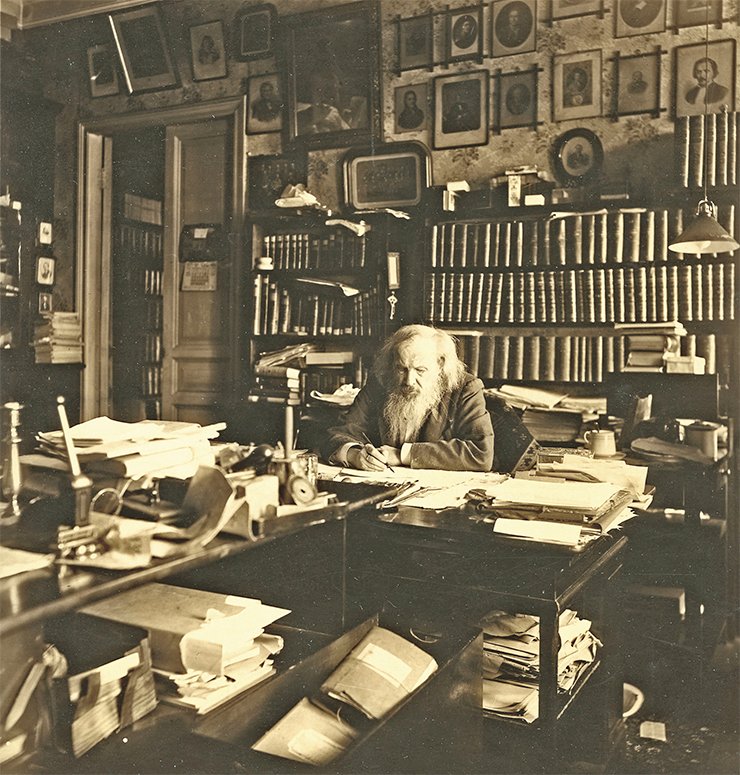

Year 2011 is the 100th anniversary of the establishment of D. I. Mendeleev Museum & Archive at Saint-Petersburg University. Three rooms of his former flat host his library, part of the archive and his home study furnishings in the Main Chamber of Measures and Weights, which Mendeleev’s students and friends bought from his wife in 1911. The home study is located in the same room in which it was located during the scientist’s lifetime. The room furnishings were modeled after the photographs taken by the Mendeleev’s employee F. I. Blumbach. In the center of his home study is a table with the things the scientist used when working are displayed: a feather pen, glasses, paperweight and rulersOn 12 March 1874, Academician N. N. Zinin presented the note written by D. I. Mendeleev and M. L. Kirpichev on the elasticity of air at reduced pressures to the Physico-mathematical Division of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. It was decided to forward the manuscript for review to Academicians N. N. Zinin and G. I. Wild. Having carefully studied the reported results (the main one was that there are deviations from the Boyle-Mariotte Law at low pressures) and inspected the equipment with the help of which the results were obtained, the scientists concluded that they were unable to make a definite conclusion about the results reported in the article. For this reason, they suggested to publish Mendeleev’s and Kirpichev’s note in the Academy’s Bulletin “under the authors’ responsibility for its content.” Further research completely confirmed Zinin and Wild’s doubts: not a single “deviation” from the Boyle-Mariotte Law exceeded the measurement error.

Academician Wild was a first-class designer of fine scientific instruments. He immediately spotted the imperfections in Mendeleev’s method. Later on, Academician P. I. Walden gave a fine and precise characteristics of Mendeleev as an experimentalist: “He had too many ideas; his quick mind was constantly concerned with new problems; his scientific imagination was inexhaustible. However, he did not have enough patience for narrow specific problems or, maybe, enough education (training) because at some point he rejected the opportunity to be schooled by the old maestro Bunsen. As an experimentalist, he was, as Americans put it, a self-made man with all its advantages and drawbacks; he sometimes saw difficulties where there were none, while at the same time he could ignore real mistakes. Nevertheless, he was an extremely precise and alert observer” (quoted from: Tyshchenko, Mladentsev, 1993, p. 154).

Academician Wild was a first-class designer of fine scientific instruments. He immediately spotted the imperfections in Mendeleev’s method. Later on, Academician P. I. Walden gave a fine and precise characteristics of Mendeleev as an experimentalist: “He had too many ideas; his quick mind was constantly concerned with new problems; his scientific imagination was inexhaustible. However, he did not have enough patience for narrow specific problems or, maybe, enough education (training) because at some point he rejected the opportunity to be schooled by the old maestro Bunsen. As an experimentalist, he was, as Americans put it, a self-made man with all its advantages and drawbacks; he sometimes saw difficulties where there were none, while at the same time he could ignore real mistakes. Nevertheless, he was an extremely precise and alert observer” (quoted from: Tyshchenko, Mladentsev, 1993, p. 154).

In March 1875, Mendeleev presented the first part of his studies on physics of gases to RTS after which he “started to receive notifications about the necessity to present further reports as soon as possible.” It was pointed out that research of gas elasticity at elevated pressures was of primary interest to the military and naval services. As for Mendeleev himself, he was interested in studying gas elasticity at reduced pressures” (ibid., pp. 184—185). He was interested in researching gases at reduced pressures because he was looking for universal ether (for more details see Dmitiriev, Scientific discovery… 2001).

As a result, the people who recommended Mendeleev to the government (Kochubey, Gadolin and RTS secretary F. N. L’vov) found themselves in a very unpleasant situation; even more so because Mendeleev was becoming more and more abrupt. In the end, he rejected the money altogether in April 1878 under a contrived pretext.

In his letter to F. N. L‘vov he wrote: “…I will not accept the money allocated by RTS for research. <…> I feel calmer and better this way. In this case my peace of mind and my “better” are more important and vital for me than what is considered respectable or disappointing for the others; it is more important even than whether you would consider my letter and refusal as a pretext for some misunderstanding. <…> I am a free Cossack and would like to remain free and will be free in any case” (Tyshchenko, Mladentsev, 1993, p. 185).

On the other hand, RTS persistence and that of the military (concerned about whether their money had evaporated in the universal ether) was understandable. In 1877—1878 the Russian-Turkish war was on; it required enormous expenses (about 1200 mln. roubles), which led the country to the brink of financial catastrophe. The government resources allocated for all the civil needs were cut to a minimum. The consequences of war (including the financial ones) were felt many years after it was over. Meantime, despite his promises and agreements, “the free Cossack” Mendeleev was dealing not with the questions in which the military were interested but was searching for the universal ether because this was his personal scientific interest.

On the other hand, RTS persistence and that of the military (concerned about whether their money had evaporated in the universal ether) was understandable. In 1877—1878 the Russian-Turkish war was on; it required enormous expenses (about 1200 mln. roubles), which led the country to the brink of financial catastrophe. The government resources allocated for all the civil needs were cut to a minimum. The consequences of war (including the financial ones) were felt many years after it was over. Meantime, despite his promises and agreements, “the free Cossack” Mendeleev was dealing not with the questions in which the military were interested but was searching for the universal ether because this was his personal scientific interest.

Subjectively, his works on the physics of gases played an important role in Mendeleev’s creative work, since one way or the other, it was connected with his works on the physics of liquids, research in meteorology, metrology, resistance of the media, aeronautics, etc. But objectively his labor-intensive research on gas elasticity which took many years did not lead to the expected appreciable results and could not compare with such scientific achievements as the Periodic Law and the concept of solutions.

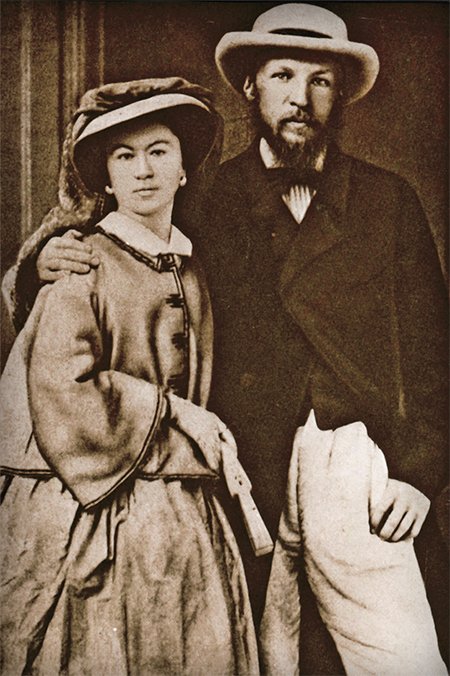

In the end of the 1870s and the beginning of 1880s, Mendeleev encountered many personal problems. He was not elected as a full member of the Academy of Sciences. He had many “external obstacles” preventing his work: his teaching overload, intensive work on publishing the second and third editions of his textbook “Principles of Chemistry,” studying the “oil cases,” conducting agricultural experiments on request of FES; his health problems (from September 1878 to May 1879 he mostly stayed abroad getting treated from pleurisy) and his family drama (getting divorced from his first wife and getting married to the second time).

In the end, all these circumstances resulted in a serious psychological crisis at the turn of the 1870s and 1880s. As A. I. Popova, Mendeleev’s second wife, remembered later, “the state of mind of Dmitri Ivanovich had a negative impact on his work and conversations. He made a will, collected all his letters to me he had written during 4 years. <…> He decided to go to the Congress in Algeria. In his own words, “On the way I wanted to fall off the deck into the sea.” He did not tell about it to anybody, of course, but Beketov and the rest noticed his condition” (Tyshchenko, Mladentsev, 1993, p. 62).

However, if the situation is concidered from the scientific angle alone, it should be pointed out that the failure of the widely planned research program on the physics of gases became a severe blow to Mendeleev. The situation was worsened by the fact that in those years the nature of physical chemistry in which he had a particular interest from his youth was undergoing drastic changes. In physics, too considerable changes were on their way. In general, it was quite unusual and sometimes even strange for Mendeleev who criticized the modern scientific thought for “getting entangled in ions and electrons.” But more than particular ideas and theories (many of which he quite rightly criticized), the style and organization of physicochemical works were foreign to him. As a result, he found himself in opposition to many significant discoveries in natural sciences of the second half of the 19th century. Having discovered the Periodic Law, he faced the necessity to choose whether to continue studying “the chemical side of the matter” (for example, a laborious analytical research of rare-earth elements which he started performing in December 1870) or to turn to the study of physical origins of periodicity. Mendeleev, the last great naturalist of the 19th century, chose the second path which led to a dead-end. The triumph of the Periodic Law became the beginning of a tragic solitude of its creator: “I am alone again.”

“Liberty, labor and duty”

However, gradually Dmitri Ivanovich gathered himself up and returned to work. Meantime, his interests changed considerably. In his works, he started devoting more and more attention to economic and technological problems, with the research on the technology and economy of the oil industry receiving prominence. Then from 1882, the Russian economy as a whole became the focus of Mendeleev’s attention. Such a change was surprising to many.

“I was told, ‘you are a chemist and not an economist, what for do you get involved in somebody else’s business?’ I have to answer to this that, first, being a chemist does not necessarily mean being aloof from plants and factories and their condition in the country and thus essentially from relevant economic problems. Second, the real, right solution to the economic problems in the future can be expected only from applying experimental methods used in natural sciences for which chemistry is one of the most important subjects. Third, not only the opinions of jury economists should be heard but also of other experts if profit for the people and the state is taken into consideration. I can see and hear that my voice is assonant with many other Russian voices” (Mendeleev, 1897, p. 62).

Traditionally, Mendeleev is considered the man of the “sixties,” i. e., a person whose world outlook was formed in the second half of the 1850s and the beginning of the 1860s, in the era of preparation to carrying out the “great reforms”. It is true that many peculiarities of Mendeleev’s mentality were close to those of a “buffer mass” of intelligentsia not of noble origin formed in the “pressure chamber” during the last years of the reign of Nikolas I and the first years of the “thaw.” It was distinguished by reckless faith in the omnipotence of methods used in natural sciences for the solution of socioeconomic problems (which served as a form of protest against the humanitarian canon for the culture of the nobility), recognition of the primacy of collective over individual, the cult of labor as the only source of human dignity, rejection of the “conventions” of elitist culture (high society), establishment of equality for women, modesty in food and clothing, intentional directness of speech, and a considerable degree of doctrinarism among other things.

At the same time, Mendeleev differed from people of the sixties. He was foreign to their rapacious, Bazarov’s nihilism and destructive energy. He was suspicious about the attitude of the “new people” to aesthetic values; he could not accept manifestations of radicalism and intolerance and many other things. Apparently, it resulted from the impact of culture of the previous “Decembrist” generation, which manifested itself in the feeling of harmony with nature, systematic mode of thinking, aversion to “street political maneuvering” as well as the style of his works, and most importantly in his belief in the positive nature of life efforts, in the ability to withstand negative external environment and to take “a tone higher.”

“Everyday life was in a flurry” People of the sixties started questioning everything from philosophical concepts to everyday life and hairstyles: high fluffy hair in women and hair divided at the back in men began to be considered a sign of vulgarity; unquestionable priority was given to the coiffure a la Chinoise done without the evident use of curling irons or anything artificial. Men belonging to the group of “new people” were so inspired by the feeling of naturalness that they did not bother to cut their bristle hair at least partially from their faces. According to I. S. Turgenev’s description, the whole lifestyle was “shaken and unstable as quagmire bog, and only one great word, “freedom,” was wafted like the breath of God over the waters” (Turgenev, I. 1980. Smoke, p. 278. Translated from Russian by John Reed. Kessinger Publishing, 2005, p. 223).As the Russian revolutionary narodnik and writer S. M. Stepnyak-Kravchinsky pointed out, the first battle of the people of the sixties with the traditionalists “was fought in the field of religion. But it was neither long, nor persistent. The victory was won at once because there is not a single country in the world where religion had so few roots among the educated layers of the society as was the case in Russia. <…> Atheism became a religion of sorts…” (Stepnyak-Kravchinsky, 2001, p. 24–25). Further he cited V. Zaitsev, a staff member of Russkoye Slovo (“The Russian Word”): “Every one of us would gladly die on the scaffold for Moleschott and Darwin.” As Stepnyak notes, “It is a very typical feature of the Russian nature to feel a passion bordering on fanaticism about the questions towards which any European would simply express his approval or reprehension” (ibid., pp. 25–26).

The ideological cohort of the people of the sixties was rather heterogeneous, although they were quite close in terms of their social behaviour. It manifested itself the most in opposing naturalness and “conditional deceit of cultural life” (P. A. Kropotkin), i.e. a good upbringing. For example, in the memoirs of his contemporaries about Mendeleev there are quite a few references to his “natural wildish Siberian nature, which did not yield to any kind of lustre” (Ozarovskaya, 1929, p. 72). Academician V. E. Tyshchenko wrote that “he was quick-tempered but also easily appeased. To listen to his screams and grumbling was not easy sometimes, but we knew that he was screaming and grumbling not because he was mean but because such was his nature. Probably, jokingly he said that it is harmful for health to keep irritation inside, it is necessary to let it out. “Curse without confusion, and you will be healthy. For example, Vladislaviev (a philosopher, the rector of Petersburg University in 1887–1890 – I. D.’s note) did not know how to curse, kept everything to himself and died early (D. I. Mendeleev in the memoirs of contemporaries, 1973, p. 48). How right wise Dmitri Ivanovich was – a well brought up person is as good as dead in Russia!

Here it is appropriate to remember a comparative characteristics of two generations of Russian intelligentsia of the 19th century given by a well-known cultural expert Yu. M. Lotman, “The fate of Russian intelligentsia of not noble origin was extremely difficult, of course, but the fate of the Decembrists was not easy either. Meanwhile, none of them first thrown in the dungeons and then after penal servitude dispersed around Siberia under conditions of isolation and material need sank morally, started drinking, gave up their spiritual world, their interests or even their appearance, habits, or the manner of expression. <…> They did not fall prey to their environment – they changed it creating such spiritual environment around themselves which was typical for them” (Lotman, 1995, pp. 146—147).

Therefore, Mendeleev adopted the features typical of different generations of Russian intelligentsia to a lesser or greater extent and gradually, as the years passed by, overcame different kinds of haughtiness characteristic of the Russian nobility” and “materialism” and utilitarianism of people of the sixties. It is possible that it was because of his “peculiarity” that his contemporaries did not (or almost did not) hear his voice.

Mendeleev’s Russia

As for Mendeleev’s economic ideas, the dominant one was that of accelerated industrialization of the Russian Empire. He thought that “the number and quality of needs” of the Russian population can only improve through the development of non-agricultural branches of industry: “there cannot be any other way out if we do not want to transform from a country that belongs to the Christian civilization to the country of Middle Asian stagnation” (Mendeleev, Letters about the plants, November, 1885, vol. 21, p. 48).

Not everybody agreed with such opinion. Mendeleev wrote, “A host of specialists, from belletrists to economists, did not understand to what stagnation the country was doomed when requiring goods of the new time but not producing them; where selling bread, deforesting our land and growing flowers of enlightenment instead of it will lead us” (Mendeleev, 1891, pp.84—85).

Leo Tolstoy, in whose novels the railway represented a “stable symbol of evil,” became one of the primary Mendeleev’s opponents among “belletrists” (Paperno, 1996, p.131). Mendeleev called Leo Tolstoy’s “lamentations” about patriarchal way of life “childish.” As he ironically noted, “the eyes of all the living look forward and about, not backwards” (cit.: Ivlev, 1951, p. 51).

On the whole, the relations between Leo Nikolaevich and Dmitri Ivanovich were distinguished by a rare reciprocity. Tolstoy said about Mendeleev’s work “To the cognition of Russia” that “in his book there is a lot of interesting material but the silliness and banality of its conclusions are horrifying” (Goldenweiser, 1959, p. 193). In his turn, Mendeleev said about Tolstoy, “He is a genius but silly… he cannot logically relate two ideas: all his constructions are purely subjective, not vital and diseased” (Tyshchenko, Mladentsev, p. 355).

Debates about whether Russia should be an agricultural or industrial country sometimes became quite sharp. Tolstoy’s Russia and Mendeleev’s Russia did not understand each other and did not even try to. A. Blok wrote about it in depth and with precision in 1908: “In our eyes, intelligentsia, which allowed Dostoevsky to die in poverty, treated Mendeleev with explicit or implicit hatred. In a way it was right: there was this “inaccessible line” (Pushkin’s phrase) between Mendeleev and intelligentsia which determines the tragedy of Russia. In recent times, this tragedy manifested itself the sharpest in irreconcilability of the two principles: Mendeleev’s and Tolstoy’s. This opposition is far sharper and more worrisome than that between Tolstoy and Dostoevsky” (Blok, 1962, 324—325).

“I do not want to contemplate this sugary thought that the first condition of “good for the people” is the satisfaction of the basic needs, i.e., the preservation of only those of them which resulted from dire necessity: food, clothing, dwelling and some spiritual needs. I don’t want to do it if for no other reason than having lived a long life, I heard such opinions only from individuals with very complicated demands, most of all from literary men…” (D. I. Mendeleev)In 1901 poor crop and hunger spread over 147 uezds in the European part of Russia with the population of 27. 6 mln. people. This disaster coincided with the economic crisis of 1899—1903 as a result of which the number of industrial workers reduced by 200,000. On the eve of 1905, the government inspection pointed out that the level of workers’ income “is approaching such a minimum that makes it impossible to provide an acceptable level of satisfaction of everyday needs (cited from Petrov, 2002, p. 359).

As Mendeleev’s assistant M. N. Mladentsev recollects, the day the Japanese started an undeclared war with Russia, he came to Dmitri Ivanovich, and they started discussing the Japanese war. “War, war is nothing…a terrible revolution is coming,” Mendeleev noted bitterly (Tyshchenko, Mladentsev, 1993, p. 381). Dmitri Ivanovich took the events of 1904—1906 very hard. He was very disappointed in many things then. “Deceit in words, their disagreement with what is done and, more importantly, a total lack of skill brought their results in Russia; they spread broadly and are difficult to reverse. Now you can hear about “liberty” everywhere and “an example” of Western Europe, but you see complete incompetence around all the same. So it seems that the results obtained on the bank from which we departed can be observed on this bank” (NAM SPbGU, II-A-10-2-20).

When Mendeleev’s socioeconomic views are discussed, many people admire the genius of the Russian scientist because his ideas about the development of national high technological production are still urgent today. In my opinion, this is not as simple as that: it is hard to say where the borderline between Mendeleev’s genius and unproductiveness of the state was, for which the same questions have remained acute for 200 years.

“Tired from a 35-year-long professorship”

In March 1890, Dmitri Ivanovich left Petersburg University, this way cutting many years of pedagogical activity short. “Tired of 35-year-long professorship, I decided to leave it behind completely; the more so because the renewed students’ upheaval influenced my fragile health. In addition, new University Rules and Regulations have evidently already started suppressing the bright side of our scientific activity and diminished the influence of pure science on the youth” (D. I. Mendeleev Archive, 1951, p. 32).

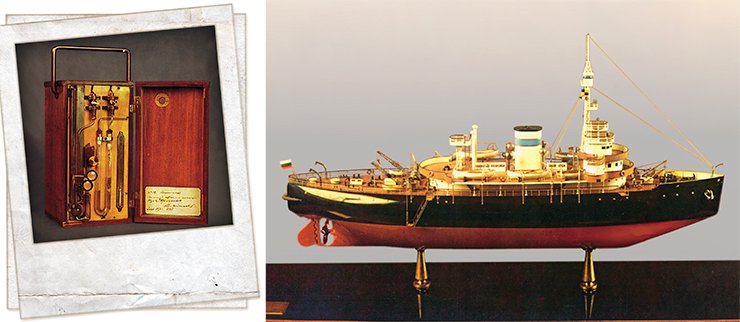

Having left the university, Mendeleev faced with a choice of fields of activity again. Since the autumn of 1890, he devoted himself almost completely to working in the area of economy and engineering: he took part in reviewing the customs’ tariffs, conducted research on making smokeless gunpowder, took part in the Urals expedition (1899), and designed an icebreaker for research in high latitudes among other things.

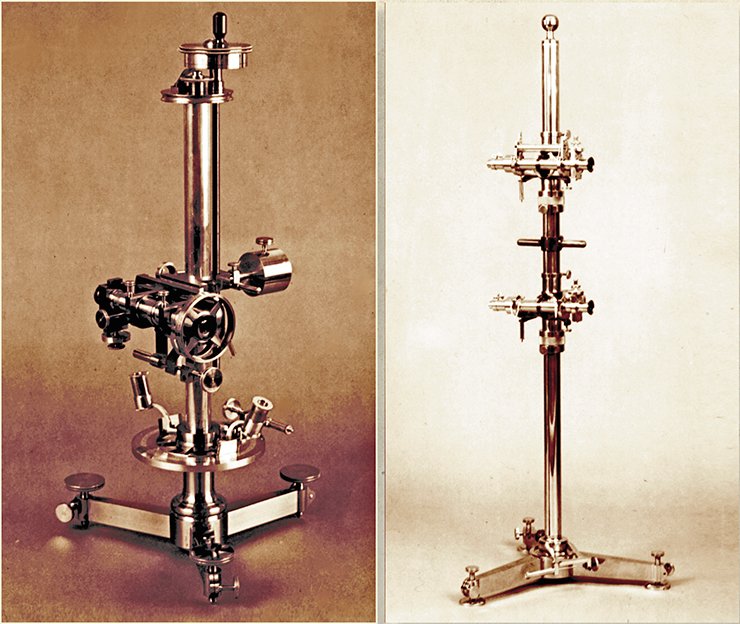

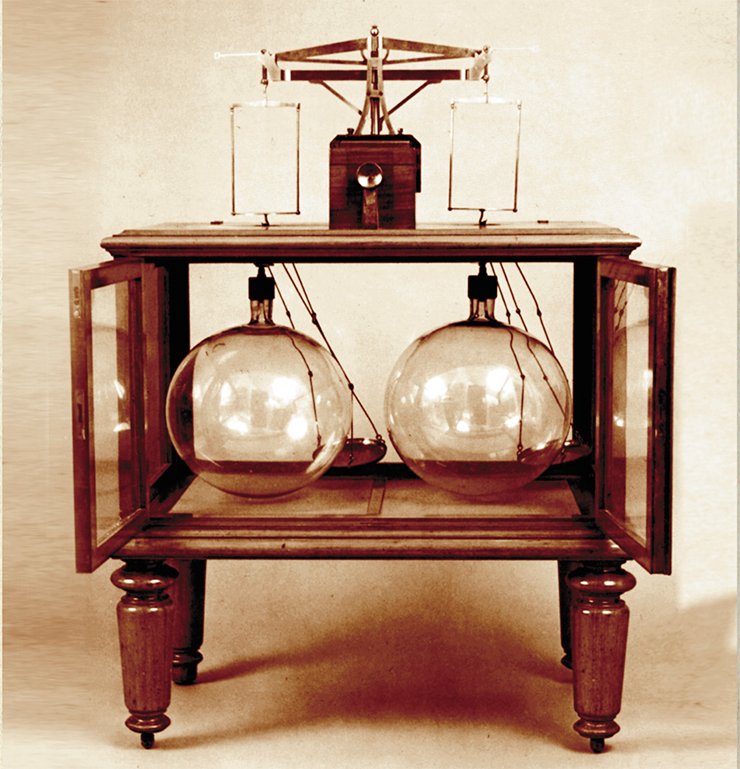

D. I. Mendeleev was one of the originators of the Russian metrology. He gave great importance to the precision of measurements already as a student. He thought that “science starts from the moment people begin to make measurements. Precise science is unimaginable without measure.” For his experiments, Mendeleev designed or constructed instruments himself; otherwise, he ordered it from the best masters. He considered the balance to be the prototype of all precise instruments. He paid particular attention to the precision of weighing, considering this type of measurement the most effective when carrying out researchIn November 1892, Mendeleev accepted S. Yu. Witte’s proposal, the then Minister of Finance of Russia, to take the post of the “Scientific Custodian” of the Depot of Standard Measures and Weights (the Main Chamber of Measures and Weights since April 1893).

By the middle 1880s, metrology as a science of precise measurements and standards acquired a great practical importance for the Russian State. Mendeleev started his work at the Main Chamber of Measures and Weights from remaking new prototypes for the main measures of length and weight and their copies as well as their scrupulous collation with the already existent European standards. As a result, already in June 1899, a new law on measures and weights was enacted in Russia. The law established the pound and the arshin as the main units of measure. Mendeleev also insisted on including an article into it allowing optional application of the international metric measures, a kilogram and a meter. Besides, he introduced several improvements in the balance construction and developed an original weighing method at a constant load.

On January 11, 1907, Mendeleev showed the Main Chamber of Measures and Weights to the new Minister of Trade and Industry D. A. Filosofov. During the inspection he caught a cold. The illness progressed rapidly, and on 20 January (2 February according to New Style) 1907, Dmitri Ivanovich passed away.

Five years before that, Mendeleev turned again to the topic of universal ether, which ran like a golden thread through all his scientific work, and wrote an article “An attempt of chemical understanding of the universal ether,” which became his peculiar scientific will in which he expressed his original views on the fundamental questions of the structure of the matter. Among other things, he wrote the following, “Chemical world outlook can be expressed in the reverse way, likening the atoms of chemists with celestial bodies – the stars, the sun, the planets, the satellites, the comets and so on. From these individual elements... systems are created, similar to the solar system and systems of double stars… in a way similar to this atoms combine into particles and particles into bodies and substances. For modern chemistry it is not a simple play on words... it is the reality which governs all research, all analyses and syntheses in chemistry. It has its own microcosm in invisible areas and being an archireal science, it constantly operates with its invisible parts not considering them to be mechanically inseparable. Atoms and particles (molecules) which inevitably become the object of study in all parts of modern mechanics and physics cannot be anything other than atoms and particles determined by chemistry which is required by the unity of cognition” (Mendeleev, 1905, p. 9).

References

Arhiv D. I. Mendeleeva. T. 1. Avtobiograficheskie materialy. Sbornik dokumentov / Sost. M. D. Mendeleeva i T. S. Kudrjavceva. Pod obshh. red. S. A. Shhukareva i S. N. Valka. L., 1951.

D. I. Mendeleev v vospominanijah sovremennikov / Sost. A. A. Makarenja, I. N. Filimonova, N. G. Karpilo. Izd. 2-e, pererab. i dop. M., 1973.

Dmitriev I. S. Nacional’naja legenda: byl li D. I. Mendeleev sozdatelem russkoj «monopol’noj» vodki? // Voprosy istorii estestvoznanija i tehniki, 1999. № 2. S. 177—183.

Dmitriev I. S. Periodicheskij zakon D. I. Mendeleeva. Istorija otkrytija. SPb., 2001. (Materialy k lekcijam. Vyp. 7).

Dmitriev I. S. Nauchnoe otkrytie in statu nascendi: Periodicheskij zakon D. I. Mendeleeva // Voprosy istorii estestvoznanija i tehniki, 2001. № 1. S. 31—82.

Mendeleev D. I. Dnevnik 1861 g. // Nauchnoe nasledstvo. Estestvennonauchnaja serija: V 4-h tt. / Pod red. H. S. Koshtojanca i dr. M., 1951. T. 2.

Mladencev M. N., Tishhenko V. E. Dmitrij Ivanovich Mendeleev, ego zhizn’ i dejatel’nost’. T. 1. M.; L., 1938.

Tishhenko V. E., Mladencev M. N. Dmitrij Ivanovich Mende¬leev, ego zhizn’ i dejatel’nost’. T. 2. Universitetskij period, 1861–1890 gg. / Otv. red. Ju. I. Solov’ev. M., 1993. (Nauchnoe nasledstvo. T. 21).